Driving Drunk, Denied Benefits: Understanding 'Gross Negligence' in Japanese Accident Insurance – A 1982 Supreme Court Case

Date of Judgment: July 15, 1982

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Case No. 1112 (o) of 1981 (Mutual Aid Benefit Claim Case)

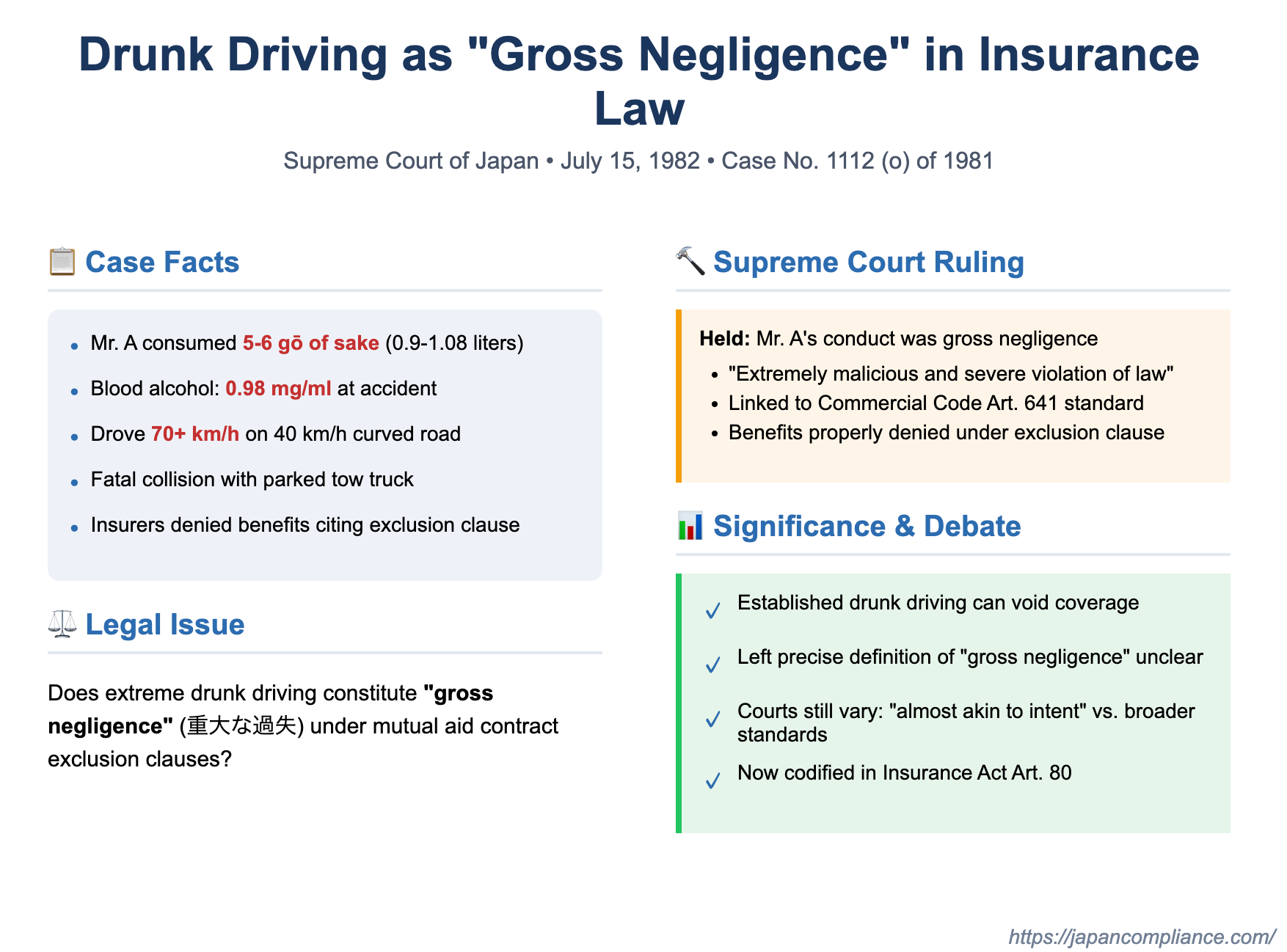

Accident insurance policies and similar mutual aid contracts are designed to provide financial protection against unforeseen injuries or death resulting from accidents. However, these contracts nearly always contain exclusion clauses, which specify circumstances under which benefits will not be paid. One common exclusion is for accidents caused by the "gross negligence" (重大な過失 - jūdai na kashitsu) of the insured person. But what level of carelessness or recklessness rises to the level of "gross negligence"? This question, particularly in the context of severe drunk driving, was addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in a significant decision on July 15, 1982.

The Fatal Collision: Facts of the Case

The case involved Mr. A, who was covered under a "life mutual aid" (seimei kyōsai) contract. This contract, provided by two agricultural cooperatives, Y1 and Y2 (the defendants and respondents), included riders for disaster benefits and supplementary disaster death benefits. A critical term in these riders was an exclusion clause: benefits would not be paid if the disaster (accident) was caused by the "intentional act or gross negligence of the covered person" (Mr. A).

On the evening of April 3, 1978, around 11:00 PM, in a suburban area of Toyohashi City, Mr. A was driving his passenger car. He collided with a tow truck that was parked on the right side of the road. Mr. A sustained severe head injuries in the crash and tragically died later that same day. This event was referred to as "the present accident."

The claimants, X1 and X2 (plaintiffs and appellants), were either the designated beneficiaries for these disaster-related benefits or had legally acquired the right to claim these benefits from the original beneficiaries. When X1 and X2 sought payment from Y1 and Y2, the agricultural cooperatives refused, asserting that the accident was directly caused by Mr. A's gross negligence, thereby triggering the exclusion clause. This led to a lawsuit.

The first instance court addressed the meaning of "gross negligence." It equated the term in the mutual aid contract's exclusion clause with the concept of "gross negligence" found in Article 641 of Japan's old Commercial Code (which dealt with insurer's exemption for losses caused by the policyholder's or insured's malice or gross negligence in the context of non-life insurance). The trial court stated that "gross negligence" under that provision did not necessarily require a state of mind "almost akin to intent." Instead, it should be determined by considering factors such as the degree of care typically required for someone in the insured's profession or status, the extent to which the insured failed in that duty, and the level of societal blame attached to such failure. The court would then decide if paying insurance benefits in such a situation would violate principles of good faith towards the insurance group or be contrary to public order and morals. Applying this broader definition, the trial court found that Mr. A's actions indeed constituted gross negligence as per the exclusion clause.

The High Court subsequently affirmed the finding of gross negligence on Mr. A's part and dismissed the appeal by X1 and X2. The claimants then appealed to the Supreme Court, primarily contesting the lower courts' determination that Mr. A had been grossly negligent.

The Legal Question: What is "Gross Negligence" in This Context?

The central legal issue for the Supreme Court was the interpretation and application of the term "gross negligence" within the mutual aid contract's exclusion clause. While the claimants argued against the finding of gross negligence on the facts, the Supreme Court's decision ultimately hinged on its own assessment of Mr. A's conduct against the legal standard for gross negligence.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Drunk Driving Was Gross Negligence

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X1 and X2, thereby upholding the denial of benefits. The Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Equivalence to Commercial Code Standard: The Court began by stating that the term "gross negligence," as used in the exclusion clause of this mutual aid contract for disaster benefits, should be interpreted as having the same meaning and intent as "gross negligence" found in Article 641 (concerning non-life insurance) and Article 829 (concerning marine insurance) of the old Commercial Code.

- Assessment of Mr. A's Conduct: The Supreme Court then meticulously reviewed the facts of Mr. A's conduct as determined by the lower court:

- On the night of the accident, Mr. A had consumed approximately five to six gō of sake (a gō is a traditional Japanese unit of volume, about 180 milliliters or 6 fluid ounces, so Mr. A had consumed roughly 0.9 to 1.08 liters, or about 30-36 fluid ounces, of sake) and was considerably intoxicated when he began driving his passenger car.

- Even at the time the accident occurred, his blood alcohol content was found to be 0.98 milligrams per milliliter.

- Under the influence of this significant amount of alcohol, Mr. A disregarded the prevailing road conditions.

- He was driving on a curved road with a posted speed limit of 40 kilometers per hour.

- He failed in his duty of forward attention and drove recklessly at a speed exceeding 70 kilometers per hour.

- As a result of this conduct, he collided with the tow truck, which was parked on the right side of the road at the time.

- Conclusion on Gross Negligence: Based on these facts, the Supreme Court concluded that Mr. A had, through an "extremely malicious and severe violation of law and reckless driving," brought about the accident himself. The Court held that this conduct squarely fell within the definition of "gross negligence" as intended by the mutual aid contract's exclusion clause.

The High Court's judgment, which reached the same conclusion, was therefore affirmed as ultimately correct.

Unpacking "Gross Negligence": A Spectrum of Interpretations

The Supreme Court's 1982 decision, while clear in its application to the extreme facts of Mr. A's drunk driving, did not explicitly provide a new definition of "gross negligence." It linked it to the existing Commercial Code standard, which itself had been subject to interpretation.

- Historical Standard ("Almost Akin to Intent"): A long-standing interpretation of "gross negligence" in Japanese commercial law, stemming from a 1913 Daishin-in (Great Court of Cassation) precedent concerning a cargo insurance policy (Taisho 2.12.20, referenced in the commentary as h55.pdf), defined it as "a state of lack of attention almost akin to intent, such as when one could easily foresee and avoid an unlawful harmful result but carelessly overlooks it and fails to prevent it". A 1957 Supreme Court decision interpreting "gross negligence" in the context of the Act Concerning Liability for Fire (Shukka Sekinin Hō) also adopted this stringent "almost akin to intent" standard. The official case investigator's commentary accompanying the 1982 Supreme Court decision suggested that this judgment, too, was following the same demanding "almost akin to intent" framework for gross negligence under Commercial Code Article 641.

- The 1982 Judgment's Own Language: However, the 1982 Supreme Court judgment itself did not explicitly reiterate the "almost akin to intent" definition. It simply stated that "gross negligence" in the contract should be interpreted in the same sense as in the Commercial Code. This has led some legal commentators to suggest that the Supreme Court might have implicitly supported the first instance court's broader definition, which did not strictly require a finding of near-intent but also considered factors like societal blameworthiness and good faith.

- Varying Standards in Subsequent Case Law: Following this 1982 decision, lower courts in Japan have not always applied a uniform definition of "gross negligence." Some have continued to use the strict "almost akin to intent" standard for both non-life insurance and accident riders. Others have used less stringent language, focusing on whether the insured failed to exercise even slight attention to foresee and avoid a readily foreseeable and avoidable harmful result. A third group of cases has followed the first instance court's approach in this case, incorporating considerations of the nature of the duty of care, societal blame, good faith, and public order.

- Insurance Act Drafters' Intent: When the current Insurance Act was drafted (enacted effective 2010), the drafters, in their explanatory notes for the new provisions on gross negligence exclusions (Article 17 for non-life insurance and Article 80 for accident and health fixed-sum insurance), referred back to the 1913 Daishin-in precedent with its "almost akin to intent" definition.

Why Exclude for Gross Negligence? Theoretical Underpinnings

The legal and theoretical justifications for excluding insurance coverage due to the insured's gross negligence are primarily twofold:

- Good Faith / Public Policy View: This traditional and still prevailing view holds that it would be contrary to the principle of good faith and fair dealing, or even public order and morals, to allow an insured person (or their beneficiaries) to receive insurance benefits for a loss that the insured themselves brought about through their own intentional wrongdoing or exceptionally reckless behavior. However, explaining the gross negligence exclusion purely on public order grounds can be challenging, as gross negligence, unlike intentional acts, does not always carry the same level of societal condemnation.

- Risk Exclusion View (有力説 - yūryoku-setsu): An influential alternative (or supplementary) theory argues that insurers, when setting premiums, calculate these based on a standard level of risk associated with fortuitous events. They do not typically price their policies to cover the significantly increased likelihood of loss that arises from an insured person's own intentional acts or their gross negligence. From this perspective, such acts fall outside the scope of the risks the insurer agreed to underwrite at the agreed premium. Policyholders, it is argued, would generally not wish to pay the much higher premiums that would be necessary to cover such self-induced, highly culpable risks. This theory does not necessarily negate the good faith arguments but suggests they alone may not fully explain the exclusion.

The Current Insurance Act and Its Implications

The landscape of Japanese insurance law has evolved since this 1982 decision. The current Insurance Act explicitly includes the insured's gross negligence as a statutory ground for exemption in "accident and health fixed-sum insurance" contracts (which includes typical accident riders on life insurance policies) under Article 80, item 1. The drafting history of this provision indicates that it was influenced by decisions like the 1982 Supreme Court case, and the intent was to codify a principle similar to that found in the old Commercial Code Article 641 for non-life insurance. The explanatory notes for the Insurance Act link the rationale for this gross negligence exclusion in Article 80 to the idea that "even in cases of gross negligence, there can be instances that violate the principle of good faith in insurance contracts". However, legal commentary suggests that this explanation does not necessarily preclude the "risk exclusion" theory as a concurrent justification.

A point of complexity arises with the proviso in Article 80, item 1, which states that even if one beneficiary intentionally or with gross negligence causes the insured event, other innocent beneficiaries may still be able to claim their share of the benefits. The "risk exclusion" theory finds it somewhat difficult to fully explain this proviso, as the heightened risk created by one party's actions would, from a pure risk perspective, affect the entire event.

The academic debate over the precise definition of "gross negligence" for insurance exclusion purposes continues. Some scholars argue for a very narrow interpretation, limiting it to "quasi-intent" or conduct virtually indistinguishable from an intentional act, on the basis that exclusions should primarily target deliberate wrongdoing. Others contend that gross negligence clauses also serve a practical role in supplementing intentional act exclusions (which can be hard for insurers to prove) and that a finding of a severe lack of ordinary care, judged by the standard of an average person, should suffice without necessarily needing to be "almost akin to intent". Proponents of this latter view, however, often acknowledge that an all-or-nothing outcome (full payment or no payment) based on a finding of gross negligence—which can sometimes be a fine line from simple negligence—is inherently harsh. Some have suggested legislative reforms to introduce principles of proportional reduction of insurance benefits based on the degree of the insured's negligence, rather than a stark denial of all benefits.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's 1982 decision powerfully affirmed that extreme misconduct, such as driving while heavily intoxicated at high speeds, can indeed constitute "gross negligence" sufficient to trigger an exclusion clause in an accident-related insurance or mutual aid contract, leading to the denial of benefits. While the judgment linked the standard to the existing Commercial Code provisions for non-life insurance, it did not provide an explicit, self-contained definition of "gross negligence," leaving room for ongoing interpretation and debate in subsequent case law and academic circles.

This case serves as a critical reminder for policyholders that their conduct can have profound implications for insurance coverage. Acts of extreme recklessness, particularly those involving severe violations of law like drunk driving, may well cross the threshold into "gross negligence," thereby voiding the financial protection that accident insurance is intended to provide. The decision highlights the enduring tension within insurance law between the system's role as a safety net for fortuitous events and its unwillingness to indemnify losses that are, in essence, self-inflicted through an insured's exceptionally culpable behavior. The varying interpretations of "gross negligence" in later cases also point to the challenge courts face in drawing a consistent line between mere carelessness and the kind of profound dereliction of care that warrants the drastic consequence of claim denial.