Drawing the Line on Fame: Japan's Supreme Court Defines Right of Publicity Infringement in the Pink Lady Case

Judgment Date: February 2, 2012

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 21 (Ju) No. 2056 (Claim for Damages)

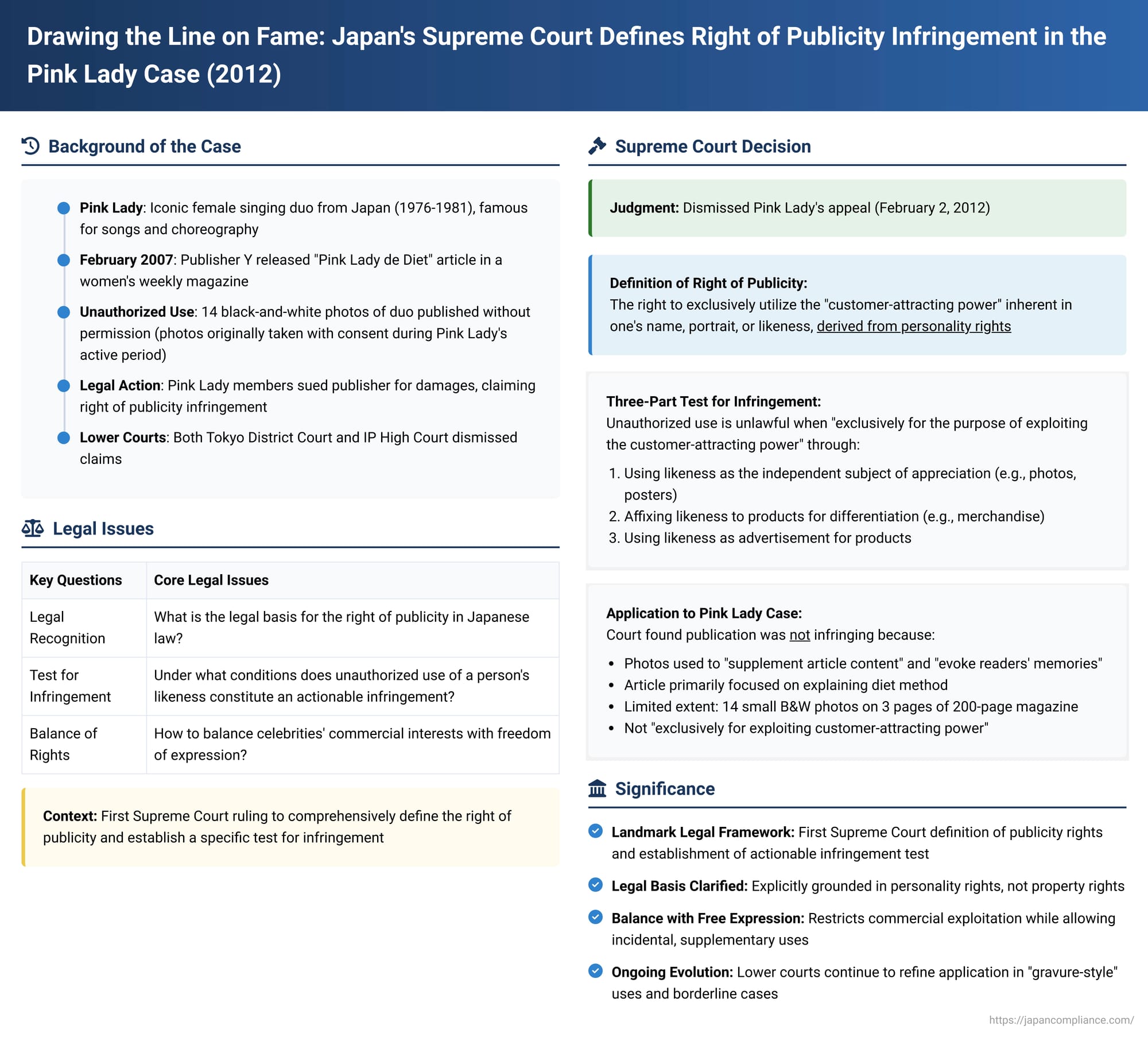

The "Pink Lady case," decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 2012, stands as a landmark judgment in Japanese intellectual property law. It was the first time the nation's highest court provided a comprehensive definition of the "right of publicity" (パブリシティ権 - paburishiti-ken), clarified its legal basis as deriving from personality rights, and established a specific three-part test for determining when the unauthorized use of a person's name or likeness constitutes an infringement actionable as a tort. This decision has since become a cornerstone for navigating disputes involving the commercial use of celebrity images and identities in Japan.

The "Pink Lady de Diet" Article: A Blast from the Past Sparks a Legal Battle

The plaintiffs (X) were the two members of the iconic Japanese female singing duo "Pink Lady." Active primarily from 1976 to 1981, Pink Lady achieved immense popularity across a wide demographic, with their songs and characteristic choreography becoming nationwide crazes.

The defendant, Company Y, was a major publisher of books and magazines. In the February 13, 2007 issue of its popular women's weekly magazine, Company Y published a feature article titled "'ピンク・レディー de ダイエット'" (Pink Lady de Diet – Dieting with Pink Lady) ("the Article"). This Article included a total of 14 black-and-white photographs of X ("the Photos") which were published without X's permission for this specific use.

The Photos themselves were not new; they depicted X during their heyday – performing on stage in costume, posing with their signature dance moves, in swimsuits, and during interviews. These photographs had originally been taken by photographers working for or on behalf of Company Y with X's consent at that time (i.e., during the 1970s and early 1980s when Pink Lady was active).

X filed a lawsuit against Company Y, alleging that the unauthorized republication of these Photos in the 2007 magazine article infringed their right to exclusively control and utilize the "customer-attracting power" (顧客吸引力 - kokyaku kyūinryoku) inherent in their likenesses – their right of publicity. They sought damages based on tort law.

Both the first instance court (Tokyo District Court) and the appellate court (Intellectual Property High Court) dismissed X's claim. The case then proceeded to the Supreme Court after X's petition for acceptance of the appeal was granted.

The Supreme Court's Framework for the Right of Publicity

The Supreme Court ultimately dismissed X's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions. However, in doing so, it laid down a foundational legal framework for the right of publicity in Japan.

I. Definition and Legal Basis of the Right of Publicity

The Court began by defining the core concepts:

- A person's name, portrait, and other aspects of their likeness (collectively, "Likenesses" - 肖像等 - shōzō tō) can possess a "customer-attracting power" that serves to promote the sale of goods or services.

- The right to exclusively utilize this customer-attracting power is what is termed the "Right of Publicity." This right, the Court stated, is based on the commercial value inherent in the Likenesses themselves.

- Crucially, the Supreme Court clarified the legal nature of this right: the Right of Publicity "constitutes one aspect of rights deriving from personality rights (人格権に由来する権利 - jinkakuken ni yurai suru kenri)."

. This was a significant pronouncement, as prior lower court decisions had varied, sometimes grounding the right in personality rights and other times in property rights. The PDF commentary highlights this as a definitive statement on the right's legal character, especially in light of a previous Supreme Court case (Gallop Racer, 2004) that had denied a right of publicity for "things" (like racehorse names) due to a lack of specific statutory basis, making the Pink Lady ruling particularly important for establishing the right for human individuals ``. - Balancing with Freedom of Expression: The Court also acknowledged an important counterbalance. Individuals whose Likenesses possess customer-attracting power often become figures of public interest and attention. As such, they must sometimes tolerate the use of their Likenesses in legitimate contexts such as news reporting, commentary, criticism, and creative works, when such use constitutes a valid act of expression.

II. The Three-Part Test for Infringement of the Right of Publicity

The Supreme Court then articulated a specific test for when the unauthorized use of Likenesses infringes the Right of Publicity and becomes actionable as a tort under Japanese law. Such use is deemed unlawful when it can be said to be "exclusively for the purpose of exploiting the customer-attracting power of the Likenesses" (専ら肖像等の有する顧客吸引力の利用を目的とする - moppara shōzō tō no yūsuru kokyaku kyūinryoku no riyō o mokuteki to suru).

The Court provided three typified examples of uses that would generally meet this "exclusively for customer appeal" criterion:

- Using the Likenesses themselves as the independent subject of appreciation in products, etc. This refers to cases where the image or name is the primary product being sold, such as collectible photographs (bromides), posters, or photo books where the celebrity's image is the main draw.

- Affixing the Likenesses to products, etc., for the purpose of differentiating those products. This covers merchandise where the celebrity's image or name is used to make the product more appealing or identifiable, such as t-shirts, mugs, or other "character goods" featuring the celebrity.

- Using the Likenesses as an advertisement for products, etc. This is the straightforward use of a celebrity's image or name to endorse or promote unrelated goods or services.

III. Application of the Test to the Pink Lady Case Facts

The Supreme Court then applied this framework to the specific use of the Pink Lady photos in Company Y's magazine:

- Customer-Attracting Power Acknowledged: The Court readily acknowledged that, given Pink Lady's immense popularity in the 1970s and 80s, the Likenesses of X in the Photos did indeed possess customer-attracting power.

- Analysis of the Article's Use of the Photos: However, when examining the actual use within "the Article," the Court noted several key factors:

- Content of the Article: The primary subject of the Article was not Pink Lady themselves or their careers. Instead, it focused on a diet method that utilized the choreography from Pink Lady's famous songs – a diet trend that had apparently gained some popularity around the autumn of 2006. The headlines highlighted the diet's supposed effects, and the text primarily consisted of illustrations and written explanations of the dance moves adapted for dieting. It also included reminiscences from another celebrity discussing their childhood experiences of imitating Pink Lady's dances.

- Limited Extent of Use: The Photos were used within only three pages of the magazine, which itself was approximately 200 pages long.

- Nature of the Photos: All 14 Photos were black-and-white, not prominent color spreads.

- Size of the Photos: The dimensions of the Photos were relatively small, ranging from approximately 2.8cm x 3.6cm to a maximum of about 8cm x 10cm.

- Court's Conclusion on the Purpose of Use: In light of these specific circumstances, the Supreme Court concluded that the Photos were used by Company Y for the purpose of "supplementing the content of the Article, such as by evoking readers' memories," while the Article itself was focused on explaining the diet method and presenting related anecdotes.

- Final Determination on Infringement: Therefore, the Court held that Company Y's unauthorized publication of the Photos in the magazine could not be said to be "exclusively for the purpose of exploiting the customer-attracting power" of X's Likenesses. Consequently, the use was not deemed unlawful as a tortious infringement of the right of publicity.

Justice Kintsuki's Supplementary Opinion: Clarifying "Exclusively"

Justice Kintsuki Seishi provided a supplementary opinion that offered further insights into the "exclusively for customer appeal" standard.

- He emphasized that because the right of publicity centers on the unauthorized use of customer-attracting power, this exploitation must be the core element of infringement.

- However, he also stressed that famous individuals are legitimate subjects of public interest and societal discourse (including entertainment-related interest in celebrities and athletes). Reporting, commentary, and criticism regarding such figures should not be unduly stifled.

- Most media (newspapers, magazines, broadcasts) operate as commercial enterprises. Any publication or broadcast featuring a celebrity's likeness might inherently have some customer-attracting effect. Therefore, broadly deeming all "commercial uses" as infringements would be inappropriate. The scope of infringement must be "as clearly and narrowly defined as possible."

- Justice Kintsuki noted that Japan lacks a specific statute codifying the right of publicity; it is a right recognized by courts as deriving from personality rights. Furthermore, harm from publicity rights infringement is primarily economic, and other harms (like defamation or privacy invasion) can be addressed through separate legal claims. These factors also support a limited interpretation of the scope of infringement.

- He viewed the three categories of use listed by the majority (likeness as product, likeness on product, likeness in ads) as typical examples of uses that are indeed "exclusively for customer appeal" and likely cover most legitimate infringement scenarios based on past lower court precedents. He suggested that other types of uses should only be considered infringing if they exploit customer appeal to a comparable degree as these three archetypes.

- Critically, Justice Kintsuki addressed a potential misinterpretation of the word "exclusively" (専ら - moppara). He cautioned that this term should not be interpreted overly strictly to mean that if any other minor purpose exists, the use is automatically non-infringing. For example, if celebrity photos are published alongside an article, a court should compare the size, prominence, and treatment of the photos versus the content and significance of the article. If the article is merely an "appendage" or pretext for publishing the photos, or if the photos are given undue prominence unrelated to any substantive textual content, then the use could still be deemed "exclusively" for exploiting customer appeal.

Legacy and Impact: A New Standard for Publicity Rights

The Pink Lady Supreme Court decision is a watershed moment for the right of publicity in Japan.

- Consolidation of Lower Court Trends: The PDF commentary explains that the Supreme Court's "exclusively for customer appeal" test, and its three typified infringing uses, largely followed and consolidated a line of reasoning that had been developing in lower court decisions, particularly those following the King Crimson appellate case

. Many lower courts had already been distinguishing between uses where photos were primary (like gravure spreads or photo books) and uses where photos were merely illustrative of a textual article. The Pink Lady judgment essentially endorsed this approach, where uses primarily aimed at journalistic or informational content (even if commercially published) with supplemental imagery were generally tolerated, while uses focusing on the images themselves as the main attraction were more likely to be found infringing. - Guidance for Future Cases: By providing a clear (albeit still interpretable) standard and typified examples, the Supreme Court aimed to increase predictability in this area of law, thereby reducing potential chilling effects on legitimate forms of expression and creativity that might involve the incidental use of celebrity likenesses ``.

- Continuing Evolution for "Gravure-Style" Uses: The PDF commentary points out that the Pink Lady case, with its focus on relatively small, black-and-white photos accompanying a textual article, did not directly rule on the more contentious issue of "gravure-style" (グラビア的 - gurabia-teki) uses, such as large, prominent color photographs in magazines that are a main feature in themselves ``.

- Post-Pink Lady lower court decisions have continued to grapple with these scenarios. For instance, the ENJOY MAX case (Tokyo District Court, 2013) found infringement for even small black-and-white photos where the accompanying text was deemed to primarily serve the purpose of arousing readers' sexual interest, and the photos themselves lacked any "independent significance" beyond exploiting the celebrity's image. This decision echoed the earlier Bubka Special 7 appellate case (Tokyo High Court, 2006), which had condemned widespread, sexually suggestive commercial exploitation of celebrity images.

- Conversely, the Shukan Jitsuwa case (IP High Court, 2015) found no infringement where a weekly magazine published black-and-white gravure photos (about 12cm in size) of female celebrities but had digitally replaced their breasts with detailed illustrations, accompanied by commentary. The court reasoned that the illustrations (intended to make readers imagine nudity), rather than the original photos, were the primary focus, and the photos served as a secondary element.

These differing outcomes indicate that the application of the Pink Lady framework to gravure-style and potentially exploitative uses is still an evolving area of law, where the specific context and perceived purpose of the use remain highly determinative.

- Other Personality Rights Remain Distinct: It is important to remember that even if a use does not infringe the right of publicity (because it's not "exclusively for customer appeal"), it might still infringe other personality rights, such as the right to privacy or protection against defamation, depending on the content of the photos or accompanying text ``. Many of the cited lower court cases, both before and after Pink Lady, also involved such claims.

- Unresolved Issues: The Supreme Court's judgment did not address certain related aspects of the right of publicity, such as its assignability or inheritability. The judicial research officer's commentary on the Pink Lady case noted these as open questions that were not foreclosed by the decision ``.

Conclusion

The Pink Lady Supreme Court case represents a critical step in the development of the right of publicity in Japan. By formally recognizing the right as deriving from personality rights and by establishing a three-part typological test centered on whether a use is "exclusively for the purpose of exploiting the customer-attracting power" of an individual's likeness, the Court provided a much-needed framework for analyzing such claims. While the "exclusively" criterion, as clarified by Justice Kintsuki's supplementary opinion, requires careful contextual application, the judgment aims to strike a balance between protecting individuals' commercial interests in their identities and safeguarding freedom of expression. The decision generally aligns with prior lower court trends that allowed for incidental or illustrative uses of likenesses in journalistic or informational contexts while scrutinizing uses that more directly commodified the celebrity image itself. The application of these principles to more borderline cases, particularly in the realm of magazine gravure and online content, continues to be refined by lower courts, making this an area of ongoing legal evolution.