Drawing the Line: Japan's Supreme Court on the Legal Force of Administrative Circulars

A Third Petty Bench Ruling from December 24, 1968

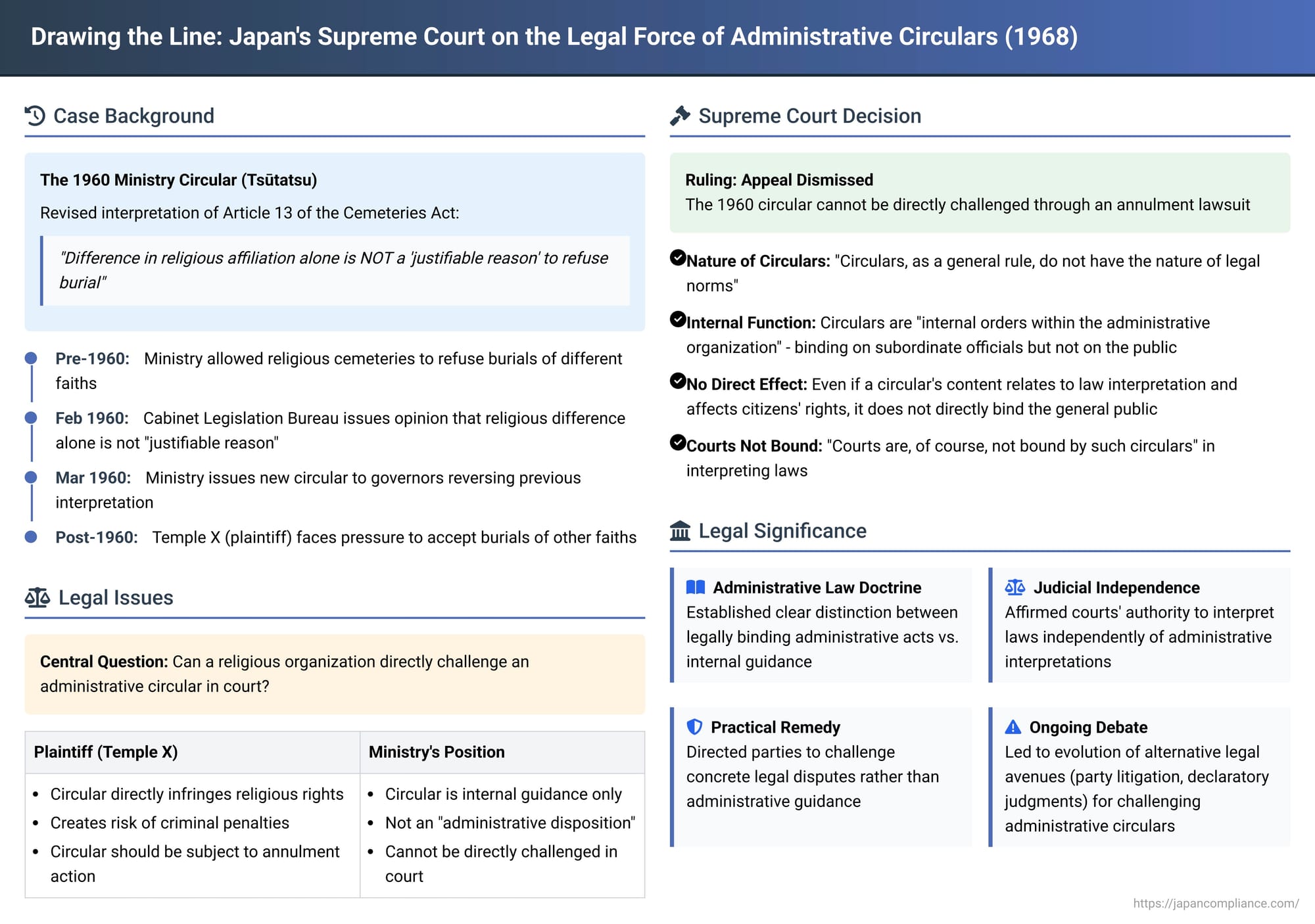

Government agencies frequently issue administrative circulars (通達 - tsūtatsu) to provide guidance to subordinate offices on the interpretation and application of laws and regulations. While these circulars play a crucial role in ensuring uniform administrative practice, their legal status—particularly whether they can be directly challenged in court by affected citizens—has been a subject of significant legal discussion. A landmark decision by the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on December 24, 1968 (Showa 39 (Gyo Tsu) No. 87), addressed this issue in the context of a Ministry of Health circular concerning the refusal of burials at cemeteries managed by religious organizations.

The Cemetery Dispute: A Clash of Faiths and Interpretations

The case revolved around Article 13 of Japan's Cemeteries and Burials Act (墓地、埋葬等に関する法律 - Bochi, Maisō-tō ni Kansuru Hōritsu, hereinafter "Cemeteries Act"). This article stipulates that "When a request for burial, interment, enshrinement, or cremation is received, the administrator of a cemetery, charnel house, or crematorium shall not refuse it without justifiable reason (正当の理由 - seitō no riyū)." A violation of this provision was subject to penal sanctions, including fines or minor detention, under Article 21(1)(i) of the same Act, making it a directly punishable offense.

The interpretation of "justifiable reason" became contentious. In August 1949, the head of the Environmental Sanitation Section of the Ministry of Health had issued a notice to the Director of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government's Sanitation Bureau. This notice suggested that for cemeteries managed by religious organizations, a "justifiable reason" to refuse burial under Article 13 could exist if accepting the burial would "gravely offend religious sentiments."

However, the social and religious landscape evolved. Conflicts began to arise between established religious organizations managing cemeteries and newly expanding religious sects whose members sought burial in these cemeteries. This led the Ministry of Health to revisit its interpretation. After obtaining an opinion from the First Department Director of the Cabinet Legislation Bureau (dated February 15, 1960), which stated that "merely being a member of a different religious sect" does not constitute a "justifiable reason" for refusal, the Ministry changed its stance.

In March 1960, the Director of the Environmental Sanitation Department of the Ministry of Health's Public Health Bureau issued a new circular (Notice Eikan Hatsu No. 8, hereinafter "the 1960 Circular" or 本件通達 - honken tsūtatsu) to all prefectural governors and mayors of designated cities. This circular announced that the Ministry was revising its previous interpretation of Article 13 of the Cemeteries Act and would henceforth interpret and apply it in line with the Cabinet Legislation Bureau's opinion—meaning, difference in religious affiliation alone would no longer be considered a "justifiable reason" to refuse burial. The circular also requested these local authorities to handle burial-related administrative affairs accordingly. At the time, the regulation of cemeteries and burials was considered an "agency-delegated function" (機関委任事務 - kikan inin jimu), where local governors acted under the direction of the national minister.

The Plaintiff's Plight: A Temple's Dilemma

The plaintiff, X, was a Buddhist religious corporation that had managed a cemetery for many years. Its long-standing practice had been not to accept the burial of individuals who were not adherents of its particular sect. X argued that the 1960 Circular caused it direct harm and disadvantage:

- It felt effectively compelled to comply with the new interpretation in the circular.

- It faced the potential risk of criminal penalties under the Cemeteries Act if it continued its traditional practice and refused burials based on differing religious affiliations, in contravention of the circular's guidance.

- X also pointed to real-world consequences, such as instances where members of its congregation who had converted to other faiths allegedly conducted burials in its cemetery without the temple's traditional rites, and other temples that had refused burials based on differing faiths had faced criminal accusations.

Believing the 1960 Circular directly and unlawfully infringed upon its rights to manage its cemetery according to its religious principles, X filed a lawsuit against Y, the Minister of Health and Welfare, seeking the annulment (取消訴訟 - torikeshi soshō) of the circular. However, both the Tokyo District Court (first instance) and the Tokyo High Court (second instance) dismissed X's suit as inadmissible. They held that the circular did not constitute an "administrative disposition" (行政処分 - gyōsei shobun) that could be the subject of an annulment action. X appealed this dismissal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision of December 24, 1968

The Supreme Court's Third Petty Bench dismissed X's appeal, affirming the lower courts' decisions that the 1960 Circular was not subject to an annulment action.

Nature of Administrative Circulars (通達 - Tsūtatsu):

The Court provided a foundational explanation of the legal nature of administrative circulars in Japan:

- The 1960 Circular was identified as a directive from the Ministry of Health and Welfare (acting through the relevant department director) to subordinate administrative organs (including prefectural governors) regarding the interpretation and application of the Cemeteries Act. It was an instruction on how they should exercise their official powers in matters under the Minister's jurisdiction.

- The Court stated that, "Originally, circulars, as a general rule, do not have the nature of legal norms (法規の性質をもつものではなく - hōki no seishitsu o motsu mono de wa naku)."

- Their primary function is to serve as internal communications within the administrative hierarchy, by which a superior agency directs subordinate agencies and their personnel on official duties. As such, circulars are essentially "internal orders within the administrative organization."

- While these internal orders are binding on the subordinate agencies and officials who receive them, they "do not directly bind the general public." This principle holds true, the Court clarified, "even if the content of the circular relates to the interpretation or handling of laws and regulations and has a significant bearing on the rights and duties of citizens."

No Direct Legal Effect on the Public or Courts:

Based on this understanding of circulars as internal administrative tools, the Court drew several conclusions about their external legal effects:

- Not Determinative of Administrative Actions' Validity: Because circulars are not inherently legal norms, "even if an administrative agency issues a disposition contrary to the purport of a circular, the validity of that disposition is not affected by that reason alone." An action is judged by its conformity with the law, not the circular.

- Not Binding on Courts: "Courts are, of course, not bound by such circulars." When interpreting and applying laws and regulations, courts can and do arrive at their own independent interpretations, which may differ from those expressed in administrative circulars. If a practice stipulated in a circular is found by a court to contravene the true meaning or purpose of the law, the court can independently determine that practice to be illegal.

Effect of the Specific 1960 Circular on X:

Applying these general principles to the 1960 Circular concerning burial refusals:

- The Court acknowledged that the circular represented a change in the Ministry's previous interpretation of the Cemeteries Act. However, it maintained that this new interpretation was binding only on the administrative organs (like prefectural governors) responsible for enforcing the Act. It did "not directly bind" the public, including X.

- Consequently, the circular could "not be said to directly infringe upon X's asserted rights to manage its cemetery or to newly impose upon X a legal duty to tolerate burials" from other sects.

- Regarding the risk of criminal penalties under Article 21 of the Cemeteries Act for violating Article 13 (refusing burial without "justifiable reason"), the Court reiterated that courts are not bound by the circular's interpretation of "justifiable reason." When a court determines whether a "justifiable reason" exists in a particular case, it "should consider circumstances other than those indicated in the circular." Therefore, the mere issuance of the circular did "not mean that X immediately faced a risk of criminal penalties."

- Any damages or disadvantages that X claimed to have suffered were, in the Court's view, "not directly caused by the circular itself."

Conclusion on Reviewability of the Circular:

The Supreme Court concluded: "Under existing law, only administrative dispositions or similar actions that directly and concretely affect the rights, duties, or legal status of citizens can be the subject of an annulment action in administrative litigation." Since the 1960 Circular did not meet this threshold of having direct, concrete legal effects on X's rights or duties, X's lawsuit seeking its annulment was deemed impermissible and was correctly dismissed by the lower courts.

Understanding "Administrative Dispositions" (行政処分 - Gyōsei Shobun) vs. Internal Guidance

This judgment hinges on the crucial distinction in Japanese administrative law between an "administrative disposition" and other forms of administrative activity, such as internal guidance or circulars.

- An administrative disposition is generally understood as an act by an administrative agency that directly determines the rights and duties of specific individuals or entities under the law, having an external legal effect. Examples include granting or revoking a license, issuing a tax assessment, or ordering a building demolition. Such dispositions are typically subject to direct judicial review through an annulment action.

- Administrative circulars, as clarified by this judgment, are primarily tools for internal administrative management and communication. They aim to achieve consistency and provide guidance to officials but are not intended to, by themselves, create new legal rights or obligations for the public or to alter existing ones established by statutes or formal regulations.

The Debate on Reviewing Circulars

The Supreme Court's consistent position, reaffirmed in this 1968 case, is that administrative circulars generally lack the "dispositive character" (処分性 - shobunsei) required to be directly challenged through an annulment suit. This is because they are seen as not directly creating or altering the legal rights and duties of the public.

However, this stance has been a subject of ongoing discussion among legal scholars and has sometimes been contrasted with lower court decisions that have, in exceptional circumstances, shown a willingness to review circulars that have particularly severe and direct impacts on citizens' rights (e.g., the Tokyo District Court's 1971 decision in the Weighing Instrument Act Circular case).

Scholars also point out that while circulars may not be directly binding on the public, they can have significant de facto influence. Principles such as the administration's self-binding to its own stated rules (a corollary of the equality principle) can sometimes give circulars indirect external relevance in judging the legality of specific administrative actions taken (or not taken) in accordance with them. Some also argue that if internal rules like circulars are themselves not unlawful, administrative bodies should generally adhere to them unless there are rational reasons to deviate.

Alternative Legal Avenues for Relief

If a circular itself cannot be directly annulled, what avenues for legal relief exist for those who believe they are adversely affected by an administrative interpretation contained in a circular?

- The Supreme Court in this case, and its judicial officer in accompanying explanations, suggested that X should seek relief when a concrete legal dispute arises. This could involve:

- Defending against criminal charges if prosecuted for allegedly violating Article 13 of the Cemeteries Act by refusing a burial. In such a proceeding, the court would independently interpret "justifiable reason," not being bound by the circular. (Though the Court here downplayed the immediate risk of penalty).

- Filing a civil lawsuit, for example, to seek an injunction against individuals attempting to force a burial contrary to the temple's rules (if those rules are otherwise lawful).

- Challenging a subsequent administrative disposition, such as a hypothetical revocation of the temple's cemetery operating permit, if such an action were taken based on non-compliance with the circular's interpretation.

- Legal commentary notes that forcing plaintiffs to seek relief only through defending criminal prosecutions can be a burdensome and inadequate remedy.

- More recent developments in Japanese administrative law, particularly revisions to the Administrative Case Litigation Act, have broadened the potential for using public law party litigation (公法上の当事者訴訟 - kōhōjō no tōjisha soshō). This type of lawsuit can sometimes be used to seek judicial review or clarification of legal relationships concerning administrative actions that do not qualify as formal "dispositions." For example, a suit for a declaratory judgment of non-obligation (義務不存在確認訴訟 - gimu fusonzai kakunin soshō) might be employed to seek a court's ruling on whether one is legally obliged to follow the interpretation set out in a circular, provided a sufficient "legal interest in seeking confirmation" (確認の利益 - kakunin no rieki) can be demonstrated. Whether the plaintiff X in this 1968 case would have met this threshold for a declaratory judgment, based on the disadvantages they claimed, is a matter for consideration. There is also a modern academic view suggesting that the strict distinction between annulment actions and party litigations might not always be necessary when seeking declaratory relief concerning administrative acts.

Significance of the Ruling

The 1968 Supreme Court decision in the Tōfukuin cemetery case remains a leading authority in Japan on the legal nature and reviewability of administrative circulars.

- It firmly established the general principle that circulars are internal administrative guidelines and not "legal norms" directly binding on the public or the courts, and therefore typically not subject to direct annulment actions.

- It underscored the judiciary's independent role in interpreting statutes and regulations, irrespective of interpretations provided in administrative circulars.

- While acknowledging that circulars can influence administrative practice and indirectly affect citizens, the ruling directed aggrieved parties to seek judicial relief through challenges to concrete administrative dispositions or in the context of specific legal disputes arising from the application of the law, rather than through direct attacks on the circulars themselves.

Conclusion

This Supreme Court judgment plays a crucial role in defining the legal landscape of administrative guidance in Japan. It draws a clear line between internal administrative communications aimed at ensuring uniform practice and formal legal norms that directly create rights and obligations for the citizenry. While the non-reviewability of circulars as "dispositions" means that parties cannot usually seek their direct annulment, the Court also affirmed that individuals are not bound by unlawful interpretations contained in circulars, and courts retain the ultimate authority to interpret the law. The ongoing evolution of administrative litigation, particularly the expanded use of public law party suits, may offer alternative avenues for addressing the impact of such administrative guidance in specific circumstances, but the core principle that circulars are not, in themselves, directly challengeable administrative dispositions remains a cornerstone of Japanese administrative law.