Drawing the Line: Japan's Supreme Court on Road Pollution, Injunctions, and the 'Tolerable Limit' of Harm

Date of Judgment: July 7, 1995

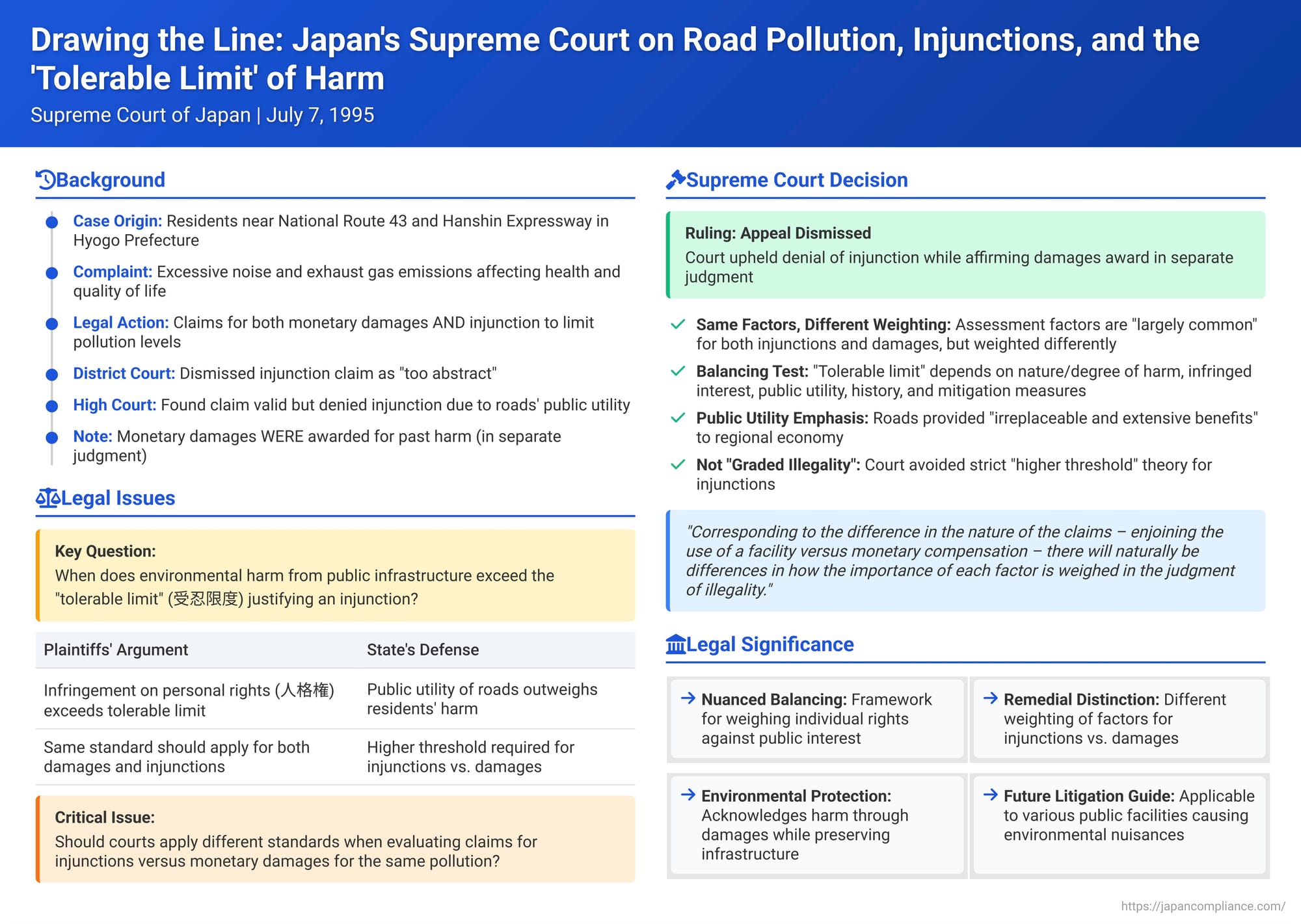

The development of public infrastructure, such as major highways, is often vital for economic growth and societal convenience. However, it can also bring unwelcome consequences for those living nearby, including persistent noise, air pollution, and a general degradation of their living environment. This raises a critical legal question: when does the harm suffered by residents cross a line, empowering them to legally demand a stop—an injunction—to such infringements, especially when the source of the harm serves a significant public purpose? And how does the standard for obtaining an injunction compare to that for receiving monetary damages for the suffering endured? The Supreme Court of Japan tackled these complex issues in a landmark decision on July 7, 1995, famously known as the "Route 43 / Hanshin Expressway" pollution case (Heisei 4 (O) No. 1504).

The Plight of the Roadside Residents: A Battle Against Noise and Fumes

The plaintiffs, X et al., were residents living near National Route 43 and associated roadways including parts of the Hanshin Expressway in Hyogo Prefecture (collectively referred to as "the Roads"). They alleged that they were suffering significant harm—including physical ailments, disruption to their daily lives, and mental distress—due to the incessant noise and exhaust gas emissions from the heavy traffic on these major arteries.

Their legal action had two main prongs: they sought monetary damages for past and anticipated future harm, and, crucially for this specific Supreme Court judgment, they sought an injunction. This injunction aimed to compel the road administrators, Y et al. (the State and the Hanshin Expressway Public Corporation), to prevent noise and nitrogen dioxide levels exceeding certain specified limits from entering their residential properties. Their claim for an injunction was based on the infringement of their personal rights (人格権 - jinkakuken).

The Journey Through the Courts: A Split Outcome on Remedies

The path to the Supreme Court was complex. The first instance court (Kobe District Court) had initially dismissed the injunction claim as being improperly formulated, deeming it too abstract because it sought the prevention of pollution intrusion without specifying the concrete measures to be taken.

The appellate court (Osaka High Court), however, found the injunction claim to be sufficiently specific and therefore procedurally valid. It laid out a framework for assessing such claims: if the residents' personal rights were found to be illegally infringed by the road pollution, they could indeed seek an injunction. The illegality of the infringement, the appellate court stated, hinged on whether the harm exceeded what a member of society could reasonably be expected to tolerate in daily life—the "tolerable limit" or junin gendo (受忍限度). This determination required a comprehensive consideration of various factors.

Significantly, the appellate court posited that the junin gendo for granting an injunction is generally stricter, demanding a higher degree of harm, compared to the junin gendo for awarding monetary damages. Applying this stricter standard to the injunction claim, the appellate court noted that the residents' harm was primarily lifestyle disruption (e.g., interference with conversations, sleep) and mental distress. Against this, it weighed the "important public mission" of the Roads in facilitating the wide-area distribution of industrial goods, emphasizing that there were no viable alternative routes. Consequently, the appellate court concluded that the infringement on the residents' personal rights, while real, did not exceed the higher tolerable limit required to justify an injunction. Their injunction claim was therefore dismissed.

In stark contrast, both the first instance and appellate courts did find that the pollution had exceeded the tolerable limit for the purpose of monetary compensation for past damages. The residents were awarded damages for the harm they had already suffered. This part of the decision was appealed by the road administrators but was ultimately upheld by the Supreme Court in a separate judgment issued on the same day as the injunction judgment (July 7, 1995, Minshu Vol. 49, No. 7, p. 1870). This divergence—illegality found for damages but not for an injunction based on the same polluting activity—set the stage for the Supreme Court's specific ruling on the injunction aspect. The residents appealed the denial of their injunction claim.

The Supreme Court's Decision on the Injunction: A Nuanced Approach

The Supreme Court, in its judgment on the injunction claim, upheld the appellate court's decision to dismiss it. The top court's reasoning provides crucial insight into how Japanese law balances public utility against private rights when injunctive relief is sought.

The "Tolerable Limit" (Junin Gendo) Standard Reaffirmed:

The Supreme Court agreed that the legality of infringements on daily life due to factors like road noise and pollution turns on whether the harm exceeds a "tolerable limit." The determination of this limit involves a comprehensive balancing of multiple factors, including:

- The nature and degree of the infringing act (e.g., pollution levels, duration).

- The nature and content of the infringed interest (e.g., health, peaceful enjoyment of property).

- The public utility or necessity of the infringing activity (e.g., the importance of the road).

- The history and circumstances of the infringing activity's commencement and continuation.

- The presence, content, and effectiveness of any measures taken to prevent or mitigate the harm.

Different Standards for Injunctions vs. Damages? Not Different Degrees of Illegality, but Different Weighting of Factors:

The Supreme Court clarified a critical point: the factors considered when assessing whether the tolerable limit has been breached are "largely common" for both injunction claims and damages claims.

However, the Court stated, "corresponding to the difference in the nature of the claims – enjoining the use of a facility versus monetary compensation – there will naturally be differences in how the importance of each factor is weighed in the judgment of illegality. Therefore, it is not unreasonable if differences arise in the determination of illegality for these two types of claims."

This means that the threshold of "illegality" itself isn't necessarily higher for an injunction, but the balancing exercise can lead to different results because the implications of each remedy are vastly different. An injunction, particularly against major public infrastructure, can have widespread societal and economic consequences, far exceeding the impact of a monetary award to specific individuals.

Application to the Route 43 Case:

In the context of the injunction sought against the Roads, the Supreme Court endorsed the appellate court's emphasis on their immense public utility. The Roads provided "irreplaceable and extensive benefits" not only to local residents and businesses but also to interregional transportation and broader industrial and economic activity.

While acknowledging the lifestyle disruptions faced by the residents and the deficiencies in preventative measures taken by the authorities (factors that were sufficient to justify damages for past harm), the Supreme Court found that these considerations were not weighty enough to overcome the profound public utility of the Roads to a degree that would warrant an injunction. Thus, for the purpose of granting an injunction, the harm had not crossed the tolerable limit. The residents' appeal for an injunction was dismissed.

Unpacking the "Tolerable Limit" and the Role of Public Utility

This judgment underscores that "public utility" is not a simple trump card that negates all claims. In the parallel damages proceedings for this very same case, the same level of public utility did not shield the road administrators from liability for past harm, especially given the finding that feasible preventive measures had not been adequately implemented.

The critical distinction drawn by the Supreme Court lies in the nature and impact of the remedy sought:

- Monetary Damages: Primarily compensate for past harm and mainly affect the financial positions of the litigating parties.

- Injunction: Seeks to stop or restrict an ongoing activity. An injunction against a major highway system like Route 43 and the Hanshin Expressway would have far-reaching consequences for countless third-party users, regional commerce, and the national economy. It is this broader impact that justifies giving greater weight to public utility when an injunction is considered.

Moving Beyond a Simple "Graded Illegality" Theory

It's important to note that the Supreme Court's decision did not explicitly adopt what had been a prevailing academic theory known as the "graded illegality theory" (違法性段階説 - ihōsei dankai setsu). This theory suggested that a higher degree of illegality was inherently required to justify an injunction compared to what was needed for a damages award. The appellate court had leaned on this theory.

The Supreme Court, however, framed its reasoning differently. It did not speak of different degrees of illegality. Instead, it focused on a differential weighting of common factors within the same overarching illegality assessment. This allows for a more flexible, context-sensitive approach, where the same factual situation can lead to different legal outcomes depending on the specific remedy sought and its potential repercussions. More recent academic thought also tends to criticize the simplistic graded illegality theory, arguing that the underlying illegality should, in principle, be the same, though public utility might exceptionally justify denying an injunction while still allowing damages.

Implications and Scope of the Ruling

The 1995 Route 43 injunction judgment has become a seminal case in Japanese environmental and tort law. It established a crucial framework for how courts evaluate requests for injunctions against public works or facilities that cause environmental nuisances. Its principles have been applied in various subsequent cases involving different types of public facilities (from community centers to private railways serving public roles) and public projects. The ruling provides a mechanism for courts to acknowledge and compensate for past harm through damages, even when an injunction, with its potentially severe and widespread disruption, is deemed inappropriate due to overriding public utility concerns.

Lingering Questions and Future Directions for Injunctive Relief

While this judgment clarified the approach for assessing injunctions against existing, highly utilitarian public infrastructure, it also left some questions open, particularly regarding the nature of the injunction sought.

The residents in the Route 43 case sought what is often termed an "abstract injunction"—they asked the court to order that noise and pollution not exceed certain levels on their property, without specifying the exact measures the road administrators should take. They were not, for instance, demanding a complete shutdown of the highways.

The commentary on this case suggests that the Supreme Court's decision might not preclude other forms of dispute resolution or more tailored injunctive relief in different circumstances. For example, if it could be demonstrated that specific, feasible mitigation measures (such as stricter speed limits, lane reductions, enhanced sound barriers, or operational restrictions during certain hours) could significantly reduce the pollution without crippling the road's essential functions, could a court then grant an injunction mandating such measures? Such an injunction could potentially be enforced through indirect compulsion (a legal mechanism to ensure compliance). Indeed, a subsequent lower court case (Kobe District Court, January 31, 2000), applying the Supreme Court's assessment framework, did affirm illegality justifying an injunction against road pollution, partly on the grounds that a complete ban on the road's use was not necessary to achieve the required reduction in pollution.

The challenge for future cases lies in clearly defining when the public utility of an infringing source genuinely necessitates the denial of any form of injunctive relief, and what specific facts and evidence parties need to present concerning the irreplaceability of the facility and the feasibility (or infeasibility) of less disruptive mitigation measures.

Conclusion: Balancing Progress and Protection

The 1995 Supreme Court judgment in the Route 43 / Hanshin Expressway injunction case is a landmark decision that navigates the complex interplay between individual rights to a healthy and peaceful living environment and the broader societal interest in essential public infrastructure. It established that while the factors for assessing the illegality of harm are common for both damages and injunctions, the weighting of these factors—particularly public utility—can differ significantly due to the disparate impacts of the remedies. This allows courts to provide monetary relief for proven harm while exercising caution in granting injunctions that could have far-reaching negative consequences on the public at large. The decision continues to shape Japanese jurisprudence on environmental disputes, emphasizing a nuanced balancing act rather than a rigid, one-size-fits-all approach.