Drawing the Line: Japan's Supreme Court on Lawful vs. Coercive Retirement Persuasion (July 10, 1980)

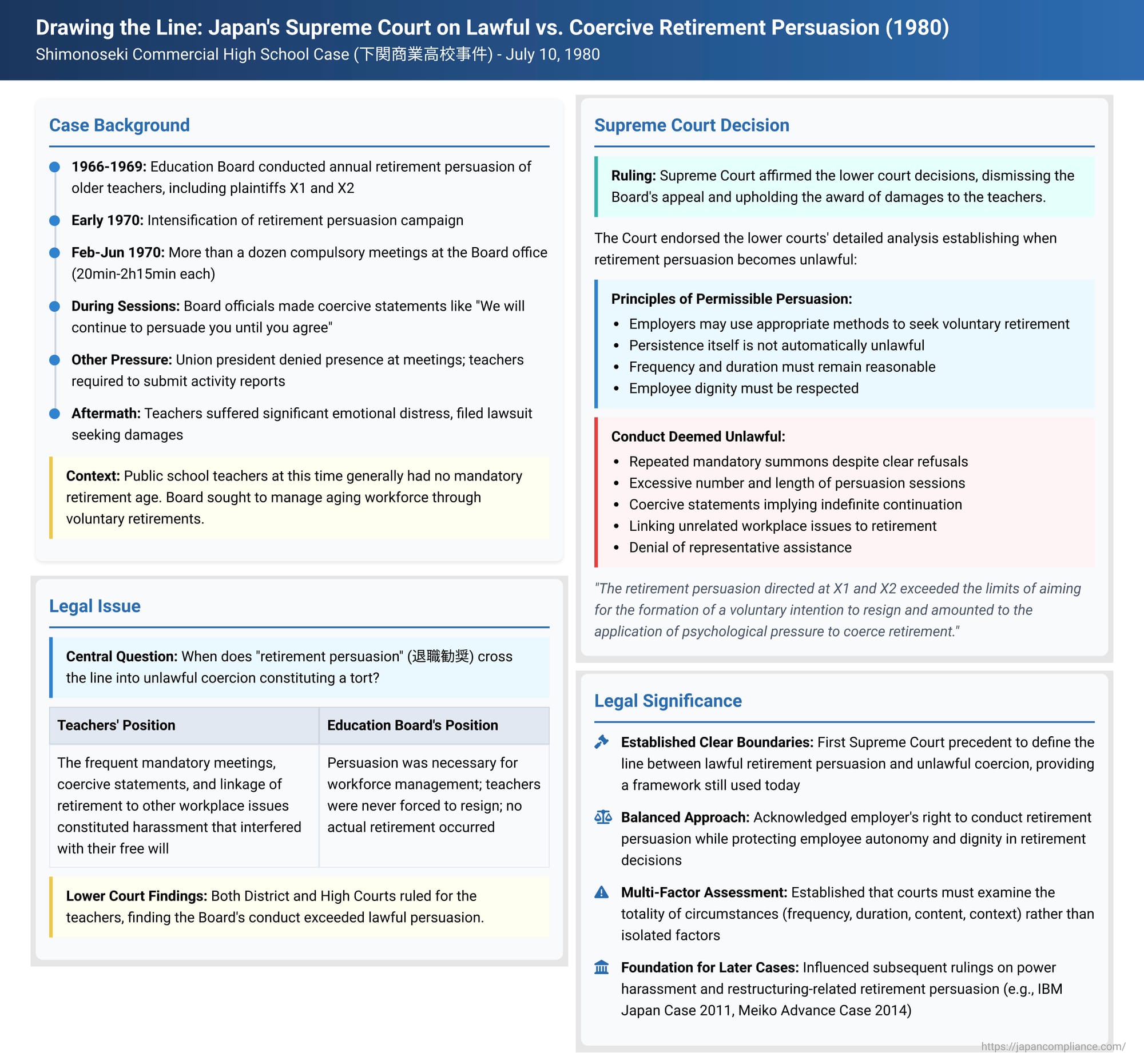

On July 10, 1980, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a judgment in a damages claim case known as the "Shimonoseki Commercial High School Case" (下関商業高校事件). This ruling, by affirming the lower courts' detailed analysis, became a significant early precedent in Japanese labor law for establishing the boundaries of permissible "retirement persuasion" (退職勧奨 - taishoku kanshō) by employers. It addressed when such efforts to encourage an employee's voluntary resignation cross into unlawful coercion and can give rise to employer liability for damages.

A Campaign of Persistent "Persuasion"

The plaintiffs, X1 and X2, were teachers employed at S Commercial High School, a public school. The primary defendant, Y1, was the City Board of Education (BoE) responsible for establishing and managing the school. Defendant Y2 held the position of Superintendent of Education, and Defendant Y3 was the Deputy Superintendent of Education.

The case arose in a specific historical context: at the time, public school teachers in Japan generally did not have a mandatory retirement age (a system-wide mandatory retirement age was not fully implemented until 1985). To manage an aging teacher workforce, promote personnel turnover, and maintain what it considered an appropriate age distribution among staff, the BoE had a policy of actively encouraging older teachers to opt for early retirement.

The facts central to the dispute were:

- Ongoing Persuasion: Plaintiff X1 had been subjected to annual retirement persuasion efforts by the BoE since the end of the Showa 40 fiscal year (early 1966), and Plaintiff X2 since the end of the Showa 41 fiscal year (early 1967). Both teachers had consistently refused these overtures up to the end of the Showa 43 fiscal year (early 1969). In March of Showa 42 (1967), the BoE had issued a notice stating that it would no longer offer any preferential treatment packages conditional upon early retirement.

- Intensification of Efforts: Towards the end of the Showa 44 fiscal year (early 1970), the BoE significantly intensified its retirement persuasion campaign directed at X1 and X2.

- Starting in February 1970, following initial persuasion attempts by the school principal, the BoE began issuing official work orders compelling X1 and X2 to report to the BoE offices for discussions.

- Over a period spanning approximately three to five months, X1 and X2 were subjected to more than a dozen such persuasion sessions. These meetings varied in length, from as short as 20 minutes to as long as 2 hours and 15 minutes each.

- Coercive Statements: During these sessions, officials from the BoE, including Deputy Superintendent Y3, made various statements to pressure X1 and X2, such as:

- "If you resign, we can hire two or three new teachers."

- "The union's demand for a significant increase in staff numbers cannot be met because you [older teachers] are still here."

- "We will continue to persuade you. No matter how long it takes, no matter how many days, until you agree, until you say yes."

- Procedural Issues: X1 and X2 had attempted to designate their union president as their representative for these negotiations, but the BoE refused to recognize the union president in this capacity and denied the union president's request to be present during the persuasion sessions. Furthermore, Deputy Superintendent Y3 ordered X1 and X2 to submit reports detailing their teaching activities or research achievements, and also suggested the possibility of transferring them to administrative positions within the BoE itself.

- Linkage to Other Workplace Issues: Concurrently, the teachers' labor union had been making demands on the BoE concerning other workplace matters, such as the abolition of the night-duty system at S Commercial High School and the filling of vacant teaching positions. The BoE consistently maintained a stance that it would not address these unrelated issues until the "retirement problem" – specifically, the retirement of X1 and X2 – was resolved. This created a situation where X1 and X2 felt distressed, worrying that they were personally responsible for the lack of progress on these broader workplace concerns.

As a result of this sustained and intensive retirement persuasion campaign, X1 and X2 claimed to have suffered significant emotional distress. They subsequently filed a lawsuit against Y1 (the BoE), Y2 (the Superintendent), and Y3 (the Deputy Superintendent), seeking damages of 500,000 yen each under Article 1, Paragraph 1 of the State Compensation Act, which governs compensation for damages caused by unlawful acts of public officials.

The Lower Courts: Finding the Line Crossed

- Yamaguchi District Court, Shimonoseki Branch (First Instance): The District Court partially ruled in favor of Plaintiffs X1 and X2. It articulated several principles for evaluating the legality of retirement persuasion:

- While employers are permitted to use various appropriate methods of persuasion to obtain an employee's voluntary consent to retire, any conduct that improperly interferes with the employee's free will or harms their sense of honor is impermissible and can constitute an unlawful infringement of rights, potentially amounting to a tort.

- Repeatedly issuing official work orders for an employee to report for the purpose of retirement persuasion, especially when the employee has indicated a desire not to retire, can itself become a form of undue pressure and render the persuasion campaign unlawful.

- Even if an employee explicitly states they do not wish to retire, further persuasion is not automatically illegal. However, if the employee's refusal is clear and definitive, continuing the persuasion without offering new conditions (such as improved retirement terms) or taking a significant break is likely to be viewed as an attempt to improperly coerce a change of mind.

- The frequency and duration of persuasion sessions must be kept within limits that are normally necessary for explanation and negotiation. Excessively numerous or prolonged sessions, unless part of a genuine ongoing negotiation, tend to increase the employee's anxiety and can constitute undue pressure.

- Retirement persuasion often involves discussion of an employee's private circumstances, including family situations, and must therefore be conducted with sufficient care to avoid harming the employee's sense of honor or causing emotional distress that could impair their ability to make a free and uncoerced decision.

- The overall legality of the persuasion attempt should be judged by comprehensively considering factors such as whether the employee was allowed to have a representative present, the number of individuals conducting the persuasion, the presence or absence of any incentives or preferential treatment for retiring, and whether the cumulative effect was to overwhelm the employee's ability to make a free decision.

Applying these principles, the District Court concluded that the retirement persuasion directed at X1 and X2 "exceeded the limits of aiming for the formation of a voluntary intention to resign and amounted to the application of psychological pressure to coerce retirement". It emphasized that however necessary early retirements might seem to the employer, because voluntary retirement is sought, coercive tactics are impermissible.

- Hiroshima High Court (Appeal): The High Court largely upheld the District Court's judgment, making some minor additions and corrections to the reasoning but affirming the finding that the BoE's conduct was unlawful.

Defendant Y1 (the BoE) appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation

The Supreme Court dismissed the BoE's appeal. In its relatively brief judgment, the Court stated: "The High Court's determination regarding the points raised in the appeal, in light of the evidence cited in its judgment, cannot be said to be unsupportable, and there is no illegality in its process as asserted in the arguments."

Essentially, the Supreme Court endorsed the factual findings and the detailed legal reasoning of the lower courts regarding the unlawfulness of the BoE's retirement persuasion tactics in this specific case. It is important to note that two justices on the panel issued a dissenting opinion, arguing that the BoE's actions were understandable given the context of managing an aging public sector workforce without a mandatory retirement age and that the persistent persuasion did not necessarily equate to unlawful coercion since the teachers ultimately did not retire. However, the majority opinion prevailed.

Defining "Retirement Persuasion" and Its Legal Standing

The Shimonoseki Commercial High School case, through the Supreme Court's affirmance of the lower courts' thorough analysis, became a key precedent in Japanese labor law concerning the limits of retirement persuasion.

- Nature of Retirement Persuasion (Taishoku Kanshō):

- Legally, taishoku kanshō is understood as a factual act by an employer aimed at encouraging an employee to decide to resign voluntarily.

- It can also possess the characteristics of a legal act, such as an employer's offer for a consensual termination of the employment contract, or an inducement for the employee to make such an offer.

- Critically, employers are generally free to engage in such persuasion, and employees are under no obligation whatsoever to accede to the employer's suggestion; the decision to retire must remain genuinely free and voluntary on the part of the employee.

- Therefore, the act of persuading an employee to retire is not, in itself, illegal.

When Persuasion Crosses the Line into Unlawful Coercion

The central issue is determining when permissible persuasion becomes impermissible coercion.

- The Guiding Standard: While this Supreme Court judgment itself did not articulate a new general standard, its endorsement of the lower courts' detailed reasoning was highly influential. A more generalized standard, often cited in subsequent cases and legal commentary, was clearly articulated in a later Tokyo District Court judgment (the IBM Japan Case, 2011): retirement persuasion becomes unlawful if it "goes beyond the limits socially accepted for forming a worker's voluntary intention to resign... and employs words or deeds that apply undue psychological pressure to the worker or unjustly harms their sense of honor, thereby being sufficient to obstruct their free decision-making".

- Illustrative Examples of Unlawful Retirement Persuasion from Case Law (as highlighted in the commentary ):

- Bullying, Harassment, and Isolation: Situations involving frequent bullying by multiple superiors, sometimes including physical violence, the assignment of meaningless tasks as a form of harassment, and actions designed to isolate the employee. The Air France Case (Tokyo High Ct., 1996) is an example. The Meiko Advance Case (Nagoya Dist. Ct., 2014), where daily verbal and physical abuse combined with retirement pressure led to an employee developing an acute stress reaction and tragically taking their own life, also falls into this category. Such actions often align with modern definitions of power harassment.

- Excessively Repetitive and Lengthy Sessions Despite Clear Refusal: Cases where employers conduct an extraordinary number of persuasion sessions over extended periods, even after the employee has clearly stated their intention not to retire. For instance, in the All Nippon Airways Case (Osaka High Ct., 2001), over 30 persuasion sessions, some very lengthy, were held over approximately four months, culminating in superiors confronting the employee at their company dormitory and using derogatory language such as calling the employee a "parasite". The context, such as the employee's health (e.g., suffering from depression as in the M.C. & P. Case, Kyoto Dist. Ct., 2014, where five 1-2 hour sessions were scrutinized), can also be critical in assessing the impact of such sessions.

- Coercive Use of Other Personnel Actions (Retaliatory Measures): Instances where an employee's refusal to retire is met with disadvantageous personnel actions intended to force their resignation. Examples include demoting a manager to a menial warehouse position after repeated refusals (Shinwa Sangyo Case, Osaka High Ct., 2013), or subjecting an employee to persistent derogatory remarks about their utility to the company followed by a transfer to a distant location requiring an extremely long commute, seemingly as a means of harassment (Hyogo Prefecture Federation of Commerce and Industry Associations Case, Kobe Dist. Ct. Himeji Branch, 2012).

- Indirect Coercion and Hostile Environment: Creating an environment so hostile that even employees not directly targeted feel pressured to resign. In the Fukuda Denshi Nagano Hanbai Case (Tokyo High Ct., 2017), a series of actions against two female employees (unjustified discipline, bonus cuts, derogatory comments about older employees) was found to constitute illegal pressure not only on them but also indirectly on two other female employees who witnessed these events and feared similar treatment.

- Contrasting Example of Lawful Persuasion: The commentary also mentions situations where retirement persuasion has been deemed lawful, such as the IBM Japan Case (Tokyo Dist. Ct., 2011). In that instance, during an economic downturn (post-Lehman shock), the company implemented a voluntary retirement support program that included enhanced severance packages and outplacement services. The persuasion was targeted at employees with lower performance evaluations, conducted by managers who had received training on appropriate interview techniques, and was carried out without demeaning the employees.

Conclusion: Protecting Employee Autonomy in Retirement Decisions

The Supreme Court's 1980 decision in the Municipal Commercial High School S (Shimonoseki Commercial High School) Case, by affirming the detailed and principled analysis of the lower courts, established crucial boundaries for the practice of retirement persuasion in Japan. It underscored that while employers have the freedom to encourage employees to consider voluntary retirement, this freedom is not absolute. Persuasion tactics that devolve into undue psychological pressure, harassment, or coercion, thereby undermining an employee's ability to make a free and uncoerced decision about their continued employment, are unlawful and can lead to employer liability for damages. This case serves as a lasting reminder of the importance of respecting employee dignity and autonomy, even when an employer is pursuing legitimate managerial objectives such as workforce restructuring. The principles it endorsed continue to guide courts in scrutinizing the fairness and legality of retirement persuasion practices.