Drawing the Line: Japanese Supreme Court on Administrative Guidance and Delayed Building Permits

Date of Judgment: July 16, 1985

Case: Damages Claim

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench, 1980 (O) Nos. 309, 310

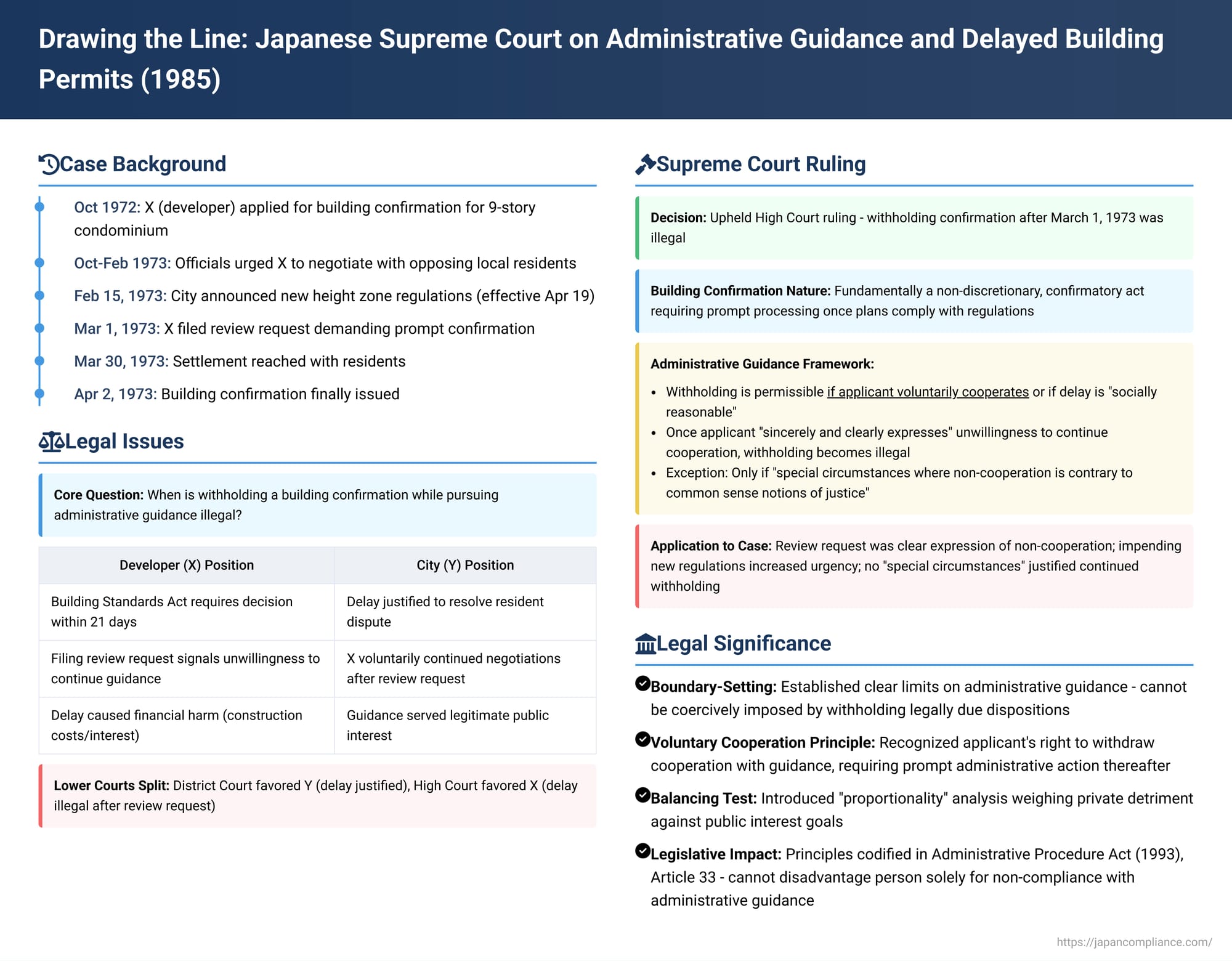

Administrative guidance (gyōsei shidō) is a pervasive feature of governance in Japan, often used by authorities to achieve policy objectives through non-coercive requests and recommendations. While it can facilitate smoother administration and dispute resolution, questions arise about its limits, particularly when it intersects with an applicant's right to a timely decision on a formal application. A landmark 1985 decision by the Supreme Court of Japan, often referred to as the "Building Confirmation Withholding Case," tackled this issue head-on, establishing crucial principles regarding when withholding a building confirmation pending administrative guidance becomes illegal and gives rise to state liability for damages.

The Factual Impasse: A Condominium Plan Meets Local Opposition and Shifting Policies

In October 1972, X, a partnership company, applied to Y, the T Metropolitan Government, for a building confirmation (a permit verifying that a building plan complies with the Building Standards Act and related regulations) for a proposed nine-story condominium with a basement.

Shortly after the application, Y's officials responsible for dispute coordination initiated administrative guidance. They advised X to engage in discussions with local residents who were opposing the construction, primarily due to anticipated significant obstruction of sunlight and other potential negative impacts on their living environment. X complied, participating in over ten negotiation sessions with the residents, actively and cooperatively responding to the advice from Y's officials, and looking to Y for appropriate mediation efforts.

The situation became more complicated on February 15, 1973, when Y announced a new draft plan for high-rise building zone regulations (a "new height zone plan") for the area, which was scheduled to take effect on April 19, 1973. Concurrent with this announcement, Y established a new policy for its administrative guidance:

- Applicants with pending building confirmations (including X) would be requested to modify their designs to align with the stricter requirements of the new height zone plan.

- Building confirmations would not be issued if disputes between applicants and local residents remained unresolved.

On February 23, 1973, Y's officials explained this new policy to X's representative, urging cooperation through design changes and recommending further negotiations with the residents. By this point, X had been negotiating with residents for several months without substantial progress. The introduction of the new height zone plan, coupled with the explicit linkage of dispute resolution to the issuance of the building confirmation, placed X in a precarious position. X concluded that an amicable resolution with residents was unlikely before the new height zone regulations came into force. If the dispute wasn't settled, X would not receive the confirmation and would be compelled to make significant design changes to comply with the new, more restrictive regulations, inevitably leading to substantial financial losses.

Believing it could no longer acquiesce to administrative guidance that was predicated on withholding the building confirmation, X decided to formally demand action. On March 1, 1973, X filed a review request (a form of administrative appeal) with the T Metropolitan Architectural Review Board, seeking prompt processing and a decision on its building confirmation application.

Despite this formal step, negotiations between X and the residents continued. On March 30, 1973, a settlement was reached, involving monetary compensation from X to the residents. Consequently, on April 2, 1973, X withdrew its review request, and Y promptly issued the building confirmation for the condominium as originally applied for.

However, X then sued Y (the T Metropolitan Government) for damages. X argued that Y's building officials had an obligation under the Building Standards Act (Article 6, Paragraph 3 at the time) to issue a decision on the building confirmation application within a specified period (then 21 days). X contended that withholding the confirmation for an extended period while coercively promoting negotiations with residents, especially under the shadow of the new height zone plan, was an illegal act that caused financial harm due to increased construction costs and interest expenses during the delay.

The Lower Courts' Differing Views

The Tokyo District Court dismissed X's claim. It reasoned that if a dispute arises between a developer and local residents concerning a building plan, and negotiations for resolution are underway, withholding the building confirmation is not necessarily illegal. Since X had continued to actively negotiate with residents even after filing its review request, the District Court found that the continued withholding of the confirmation was based on just and reasonable grounds and therefore not unlawful.

The Tokyo High Court, however, took a different stance and partially accepted X's claim. The High Court found that once X, by filing the review request on March 1, 1973, had clearly expressed its unwillingness to further comply with administrative guidance that involved delaying the confirmation, any subsequent withholding of the confirmation lacked legitimate grounds and was therefore illegal. Y appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, and X filed a cross-appeal (presumably on the extent of damages or the period of illegality).

The Supreme Court's Landmark Judgment: Defining the Boundaries of Guidance

On July 16, 1985, the Supreme Court delivered its judgment, dismissing both Y's appeal and X's cross-appeal. This effectively upheld the High Court's finding that the T Metropolitan Government was liable for damages caused by the delay in issuing the building confirmation from March 1, 1973, onwards. The Supreme Court's detailed reasoning set a crucial precedent.

I. The General Principle: Withholding Confirmation During Administrative Guidance:

The Court first acknowledged the legal framework. The Building Standards Act (then Article 6, Paragraphs 3 and 4) stipulated a processing period (21 days for this type of building) within which the building official, upon receiving an application, must examine the plans for compliance with relevant laws and regulations. If compliant, a confirmation notice must be issued. The purpose of this time limit, the Court noted, was to ensure prompt responses to applicants, considering the preparatory burdens on them (financing, temporary relocation, etc.) and to balance regulatory control with the freedom of construction.

The building confirmation itself, the Court affirmed, is fundamentally a non-discretionary, confirmatory act. Once the plans are found to comply with legal requirements (and any necessary consents, e.g., from the fire chief, are obtained), the building official has a duty to issue the confirmation promptly.

However, this duty is not absolute. The Court allowed for exceptions:

- Withholding confirmation might be permissible if the applicant voluntarily consents to the delay.

- Even without explicit consent, withholding might be acceptable if, under all circumstances, it is deemed "socially reasonable" (社会通念上合理的 - shakai tsūnenjō gōriteki) in light of the law's objectives.

The Court then specifically addressed administrative guidance aimed at resolving disputes between a developer and local residents (e.g., over sunlight obstruction, which impacts the living environment – a concern relevant to the public welfare objectives of the Building Standards Act). If such guidance is provided, and the applicant voluntarily cooperates with it (e.g., by negotiating with residents), then withholding the building confirmation for a "socially reasonable period" while awaiting the outcome of the guidance is not immediately illegal. This acknowledges the practical reality that building projects can have "dual effects" (複効的行政行為 - fukkōteki gyōsei kōi), benefiting the applicant but potentially harming neighbors, often necessitating such interest-adjustment guidance.

The crucial turning point, however, is the applicant's stance:

- The act of withholding confirmation is essentially a de facto measure, predicated on the applicant's voluntary cooperation and compliance with the administrative guidance.

- If an applicant clearly expresses their unwillingness to accept further delay of their confirmation while such guidance is ongoing, then forcing them to endure continued withholding against their explicit wishes is impermissible.

- In such cases of an applicant's expressed non-cooperation or non-compliance, withholding the building confirmation solely on the grounds that administrative guidance is still in progress is illegal.

- The only exception to this illegality is if there are "special circumstances where the applicant's non-cooperation can be said to be contrary to common sense notions of justice" (社会通念上正義の観念に反するものといえるような特段の事情 - shakai tsūnenjō seigi no kannen ni hansuru mono to ieru yōna tokudan no jijō). This determination requires a comparative balancing of the detriment suffered by the applicant against the public interest needs pursued by the administrative guidance.

II. When Cooperation Ceases:

The Court elaborated that even if an applicant initially agrees to cooperate with administrative guidance and enters into negotiations, if the progress of those discussions and the surrounding objective circumstances lead the applicant to "sincerely and clearly express" to the building official that they can no longer cooperate with guidance that is tied to withholding their confirmation, and they demand an immediate response to their application, then further withholding based on the ongoing guidance becomes illegal—unless the aforementioned "special circumstances" exist.

III. Application to X's Case:

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found:

- X's act of filing the review request with the Architectural Review Board on March 1, 1973, was a "sincere and clear expression" of its unwillingness to tolerate further delay of the building confirmation due to ongoing administrative guidance, and a demand for immediate action on its application.

- X had initially cooperated with Y's guidance. The failure to resolve the dispute with residents up to that point could not be solely attributed to X. Moreover, Y later introduced new guidance requesting design changes based on a new height zone plan announced after X's application, with the enforcement of this new plan imminent (just over a month away).

- Given these circumstances—especially the pressure of the impending new regulations which threatened X with significant losses if the confirmation was not issued for the original plan—X's decision to signal its non-cooperation via the review request was not unreasonable.

- The Court found no "special circumstances" that would make X's refusal to continue tolerating the delay "contrary to common sense notions of justice."

- Y's officials (both the dispute coordinators and the building official) knew, or should have easily known, from the history of guidance, the content of the review request, and the timing of X's action, that X's demand for prompt confirmation was serious and not merely a tactical maneuver or an emotional outburst.

- Therefore, the T Metropolitan Government's withholding of the building confirmation from March 1, 1973 (the date X filed the review request) onwards, on the grounds of ongoing administrative guidance, was illegal. The Court also found that the building official was, at the very least, negligent in this illegal delay.

The Supreme Court thus affirmed the High Court's judgment holding Y liable for damages incurred by X due to the delay from March 1, 1973, until the confirmation was eventually issued.

Dissecting the "Special Circumstances" Rule and Its Foundations

This 1985 Supreme Court judgment is considered a leading case, forming the basis for Article 33 of Japan's Administrative Procedure Act (enacted in 1993), which deals with administrative guidance. The ruling offers a sophisticated "two-stage legal evaluation" or "intermediate theory" for assessing the legality of withholding a formal disposition while administrative guidance is in progress:

- Balancing of Interests: The first stage involves a comparative balancing of the applicant's detriment (in X's case, the financial losses from construction delay compounded by the risk of being forced into costly design changes due to the new height zone plan) against the public interest pursued by the administrative guidance (here, the amicable resolution of disputes with neighbors to protect their living environment).

- "Common Sense Notions of Justice": If this balancing indicates that the applicant's detriment is excessive or disproportionate to the public interest being served by continuing the guidance against the applicant's will, then the applicant's non-cooperation—provided it's part of legitimate economic activity and not inherently unreasonable—is generally not considered "contrary to common sense notions of justice." In such a scenario, continued withholding becomes illegal.

Underlying this framework is a consideration akin to the proportionality principle. As the PDF commentary suggests, the impending enforcement of the new height zone plan dramatically increased the potential harm to X. This shift in circumstances likely altered the balance of interests, making the continued withholding of the confirmation (a measure previously tolerated during X's cooperation) disproportionate to the goal of dispute resolution, especially once X clearly signaled its desire for the processing of its valid application. The fact that X had engaged seriously with the guidance and ultimately reached a monetary settlement with the residents also likely factored into the Court's assessment that X's eventual stance was not unreasonable.

It's also relevant that while the Building Standards Act sets processing time limits for building confirmations, these are generally interpreted by courts not as absolute, unyielding deadlines but as imposing a "relative duty" on the administration —a view the Supreme Court implicitly adopted by allowing for some justifiable delays under specific conditions.

Context and Implications

The Supreme Court's 1985 decision provides an essential framework for understanding the limits of administrative guidance in Japan, especially when it is linked to the processing of formal applications.

- It acknowledges the practical utility and often necessity of administrative guidance for resolving complex issues like neighborhood disputes arising from development projects.

- However, it firmly establishes that an applicant's voluntary cooperation is the cornerstone of legitimate administrative guidance. Guidance cannot be indefinitely or coercively imposed by withholding a legally due disposition against the applicant's clear and reasonably expressed will.

- The "special circumstances where non-cooperation is contrary to common sense notions of justice" provides a narrow exception, requiring a careful balancing of public and private interests and a high threshold for the administration to meet if it wishes to continue withholding a disposition despite an applicant's refusal to cooperate further with guidance.

This ruling has had a lasting impact on administrative practice, reinforcing the idea that while informal guidance is a valuable tool, it must not unduly trample upon the procedural rights of applicants seeking formal administrative decisions.

Conclusion: Balancing Guidance with Procedural Rights

The 1985 Supreme Court judgment in the "Building Confirmation Withholding Case" is a seminal decision in Japanese administrative law. It carefully navigates the delicate balance between the use of administrative guidance as a means of achieving public policy goals and resolving disputes, and the right of an applicant to receive a timely decision on a lawful application. By setting clear limits on how long an administrative body can withhold a formal disposition while pursuing administrative guidance, especially once an applicant signals non-cooperation, the Court fortified protections against potential administrative overreach and undue delay. This case remains a critical reference for understanding the fair and lawful application of administrative guidance in Japan.