Drawing the Line at the Border: Japan's Supreme Court on Customs, Censorship, and Obscenity

Judgment Date: December 12, 1984, Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

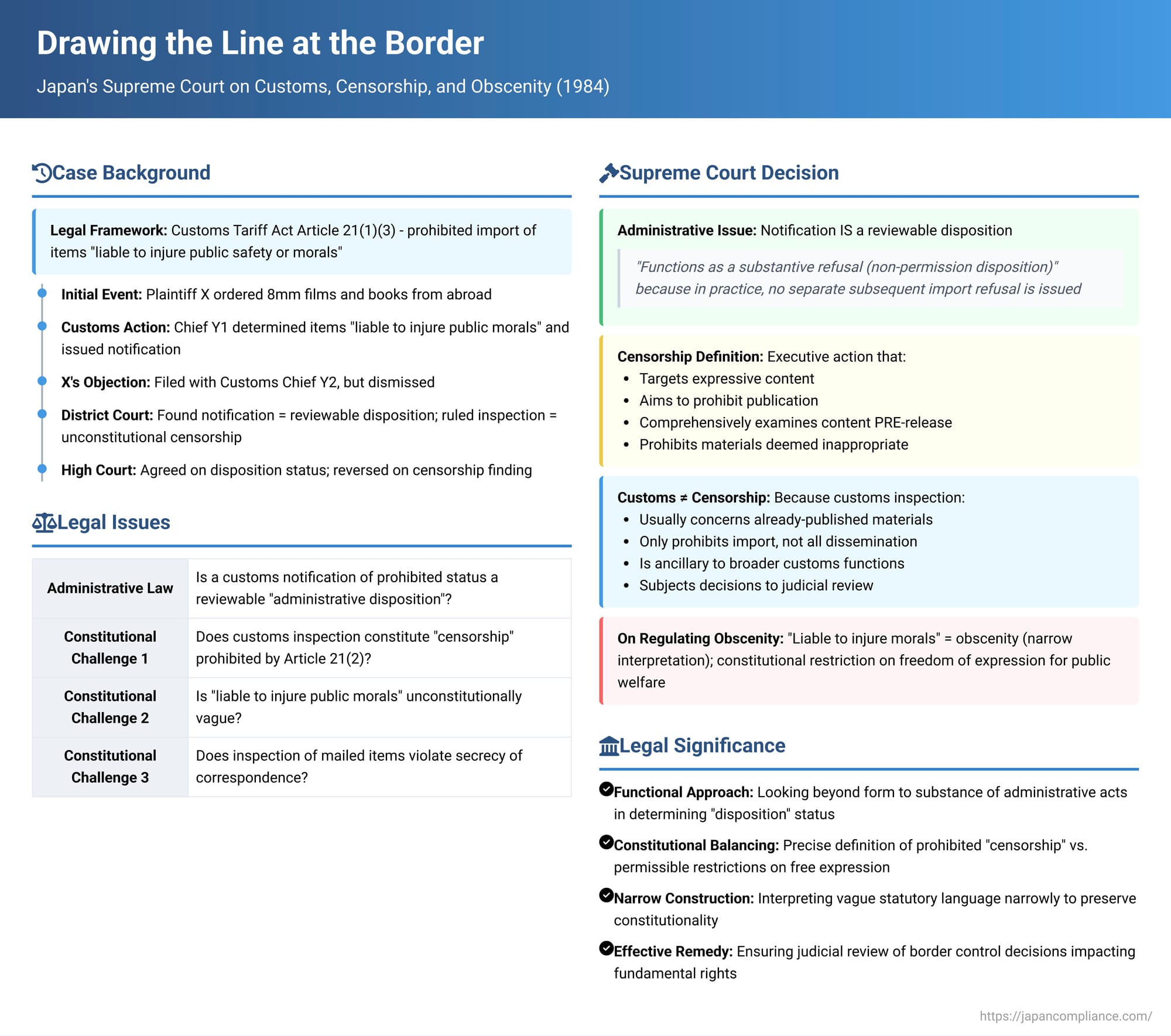

The flow of goods across international borders is a vital aspect of modern life, but it also presents challenges for states seeking to uphold their domestic laws and public standards. One such challenge involves materials deemed "injurious to public safety or morals." In Japan, the customs authorities play a key role in interdicting such items. A landmark 1984 Supreme Court decision delved into the constitutional and administrative law complexities surrounding this process, particularly whether a customs notification deeming items import-prohibited constitutes a reviewable "administrative disposition" and whether such inspections amount to unconstitutional censorship.

The Legal Framework: Prohibiting Imports Injurious to Public Morals

At the time of the case, Japan's Customs Tariff Act (specifically Article 21, Paragraph 1, Item 3, a provision later moved and amended within the Customs Act) listed categories of goods prohibited from import. Among these were "books, drawings, sculptures, or other articles liable to injure public safety or morals".

The procedure for handling such goods involved customs inspection. If, as a result of this inspection, the Customs Chief (or a delegated official) had reasonable grounds to believe that imported goods fell into this prohibited category, they were required to notify the intended importer of this determination (Article 21, Paragraph 3). The importer then had the right to file an objection with the Customs Chief. Following such an objection, the Customs Chief would make a decision and notify the objector (Article 21, Paragraphs 4 and 5; these objection provisions were later revised, with current law providing for administrative review requests followed by litigation). Importing prohibited items or importing without proper permission could lead to criminal penalties. Importantly, established customs practice at the time was that if such a notification of prohibited status was issued, no separate "import non-permission" disposition was subsequently made; the notification itself served as the effective barrier to import.

For postal items, while formal import declarations and permissions were generally not required, items other than letters were still subject to customs inspection. The notification and objection process for prohibited items found in mail was similar to that for general cargo.

The Case: Imported Films and Books Stopped at Customs

The plaintiff, X, had ordered several items from a foreign company, including 8mm movie films and books, intending to import them into Japan by mail. Upon inspection, Y1 (the Chief of the Sapporo Customs Branch, acting under the authority of Y2, the Hakodate Customs Chief) determined that these items were "liable to injure public morals" and thus fell under the import prohibition of Article 21, Paragraph 1, Item 3 of the Customs Tariff Act. Y1 duly notified X of this determination, meaning X could not receive the items. X filed an objection with Y2, but this objection was dismissed.

X then initiated legal proceedings, seeking the revocation of both the initial notification and the decision dismissing his objection. X raised several significant constitutional arguments, claiming:

- The customs inspection itself constituted "censorship," which is absolutely prohibited by Article 21, Paragraph 2 of the Constitution of Japan.

- The phrase "liable to injure public safety or morals" in the Customs Tariff Act was unconstitutionally vague, violating Article 21, Paragraph 1 (freedom of expression), Article 29 (property rights), and Article 31 (due process).

- The inspection of postal items violated the secrecy of correspondence, also protected by Article 21, Paragraph 2.

The Sapporo District Court (First Instance) found that the customs notification and the dismissal of the objection were indeed reviewable administrative dispositions. On the merits, it agreed with X that the customs inspection in this specific case amounted to unconstitutional censorship and granted X's request to revoke the customs actions.

The Sapporo High Court (Second Instance), on appeal by the customs authorities, also recognized the dispositional character of the notification and dismissal. However, it disagreed on the constitutional issue, finding that the customs inspection did not constitute prohibited censorship. Consequently, it reversed the first instance judgment and dismissed all of X's claims. X then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench Decision (December 12, 1984)

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court ultimately dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision to reject X's claims. However, the Supreme Court's reasoning provided crucial clarifications on both the administrative law question of "dispositional character" and the constitutional issues raised.

Part 1: The Customs Notification is a Reviewable "Administrative Disposition"

The Supreme Court first affirmed that the customs notification (and the subsequent decision on objection) indeed qualified as an administrative disposition subject to an administrative appeal lawsuit.

- The Court acknowledged that even if the law itself declares certain goods import-prohibited, the practical application of this prohibition requires a prior determination by the Customs Chief that the specific goods in question actually fall into that prohibited category. This determination is an "exercise of administrative power" distinct from ordinary judgment.

- The Court noted that judging whether an item is "liable to injure public safety or morals" involves a value judgment and is not always self-evident, especially compared to items like narcotics whose prohibited status might be clear from their physical nature.

- Crucially, the Court looked at established customs practice. When goods were deemed to fall under the "public safety or morals" clause (Item 3), the Customs Chief would issue the notification as per Article 21, Paragraph 3. Significantly, no separate, subsequent "import non-permission" disposition was issued. This notification was, in effect, "the final expression of the customs authority's refusal to allow importation." This applied equally to postal items, for which there was no formal import declaration and permission process.

- Once such a notification was issued, the importer could not legally take possession of the goods from the bonded area, or in the case of mail, receive delivery from postal authorities.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that in the actual practice of customs procedures, this notification "functions as a substantive refusal (non-permission disposition)." As such, both the initial notification and the decision on an objection to it were deemed administrative dispositions reviewable by the courts. (The Court also noted that subsequent legislative amendments had explicitly provided for administrative review requests and revocation lawsuits concerning such notifications).

Part 2: Customs Inspection is Not Unconstitutional "Censorship"

The Court then addressed X's primary constitutional claim that customs inspection amounted to censorship, which Article 21, Paragraph 2 of the Constitution absolutely prohibits. The Court provided a detailed analysis to distinguish customs inspection from prohibited censorship:

- Definition of Censorship: The Court defined "censorship" as an act by the executive branch that involves:

- Targeting expressive materials based on their thought content.

- Aiming to prohibit the publication/dissemination of all or part of such materials.

- Comprehensively and generally examining the content of targeted expressions before their public release.

- Prohibiting the release of materials deemed inappropriate.

- Historical Context: The Court noted that this constitutional prohibition was based on historical experiences, both in Japan (under the Meiji Constitution with laws like the Publication Act and Newspaper Act, and specific censorship of films) and abroad, where such systems severely restricted freedom of thought and expression.

- Distinguishing Features of Customs Inspection:

- Post-Publication (Usually): Customs inspection typically targets materials already published or released in foreign countries; it's not a restraint prior to any initial public dissemination.

- Import Prohibition, Not Total Ban: The items are prohibited from import into Japan, but this doesn't mean they are confiscated and destroyed by customs, nor does it completely deny all possibility of expression (e.g., they might still exist or be disseminated outside Japan).

- Ancillary to Customs Duty: Customs inspection is part of the broader customs and tariff collection process. Its primary purpose is not to comprehensively examine and regulate thought content itself, even though it incidentally affects items containing expression.

- Judicial Review Available: Unlike historical censorship systems where administrative judgment was often final, decisions made during customs inspection (like the notification in this case) are subject to judicial review.

Based on these distinguishing factors, the Supreme Court concluded that customs inspection of items potentially falling under the "public safety or morals" clause does not constitute "censorship" as prohibited by Article 21, Paragraph 2 of the Constitution.

Part 3: Regulating Obscenity is a Permissible Limit on Free Expression

The Court then considered whether the import restriction violated the broader guarantee of freedom of expression under Article 21, Paragraph 1, particularly regarding the alleged vagueness of "liable to injure...morals."

- Narrow Construction of "Morals": The Court held that the phrase "liable to injure...morals" in the context of books and drawings should be interpreted narrowly to refer to "obscene materials." This interpretation was supported by looking at the history of Japanese law, particularly the Penal Code's provisions against distributing obscene materials, which have long focused on sexual morality.

- Obscenity and Public Welfare: The Court reaffirmed its stance that freedom of expression, while a fundamental right, is not absolute and can be subject to restrictions for the public welfare. Maintaining a minimum standard of sexual morality and protecting society from the harm of obscenity falls within the scope of public welfare. Restricting the import of obscene materials was thus a permissible means to achieve this legitimate public welfare objective.

- Addressing Vagueness: By interpreting "injurious to morals" as "obscene," the Court found that the law was not unconstitutionally vague. The concept of obscenity, it noted, had been clarified through an accumulation of case law related to the Penal Code, providing a sufficiently clear standard for individuals to understand what is prohibited. This limited construction ensures that only materials that can be constitutionally regulated (i.e., obscene materials) are targeted, without unduly chilling constitutionally protected expression.

- Impact on "Right to Know": The Court acknowledged that prohibiting the import of such materials restricts the public's "right to know" or access information. However, given that the distribution of obscene materials is already restricted domestically, the Court found this limitation on access to imported obscene materials to be a justifiable and unavoidable consequence of upholding public sexual morality.

Part 4: Secrecy of Correspondence Not Violated

Regarding X's claim that the inspection of postal items violated the secrecy of correspondence (also guaranteed by Article 21, Paragraph 2), the Court quickly dismissed this. It pointed out that the Customs Act (Article 76, Paragraph 1, proviso) explicitly states that customs inspection of mail applies only to items other than letters (信書 - shinsho). Since the items X sought to import were films and books, not letters, the secrecy of correspondence was not implicated.

Part 5: Application to X's Items

Finally, the Supreme Court upheld the High Court's factual determination that the specific items X attempted to import were indeed obscene and therefore fell under the category of "books, drawings...liable to injure...morals" as interpreted by the Court.

The "Dispositional Character" of Notifications: A Closer Look

This 1984 Grand Bench decision built upon and solidified an earlier 1979 First Petty Bench Supreme Court precedent which had also found a similar customs notification to be an administrative disposition. The key factor in these rulings is the substantive function of the notification within the overall customs procedure. Although merely labeled a "notification," it operates as the definitive administrative act that prevents the import of the goods, thereby directly impacting the importer's rights to possess and use those goods within Japan.

This approach of looking at the practical effects and the overall administrative "mechanism" to determine dispositional character can be seen in other Supreme Court cases as well. For instance, a notification of a violation of the Food Sanitation Act, which could trigger further administrative disadvantages, was also found to be a reviewable disposition, as was a notice of termination (abolition) of a designated facility for hazardous substances which directly impacted the facility operator's legal status. These cases indicate a judicial willingness to look beyond mere labels and assess the real-world impact of administrative communications on citizens' rights.

Balancing Free Expression with Public Morals

A significant aspect of this judgment is the Court's effort to balance the fundamental right to freedom of expression with the state's legitimate interest in upholding public morals. The Court achieved this by:

- Narrowly construing the potentially broad statutory phrase "injurious to public morals" to mean specifically "obscene materials." This was essential to save the law from being struck down as unconstitutionally vague, which could have had a chilling effect on legitimate expression.

- Affirming that the regulation of obscenity is a permissible restriction on free expression when justified by the public welfare.

This approach reflects a common judicial technique: when a statute is capable of both a broad, potentially unconstitutional interpretation and a narrower, constitutional one, courts will often adopt the narrower construction to uphold the law while protecting fundamental rights.

The "Effective Remedy" Principle in Broader Context

While the 1984 decision did not explicitly hinge its dispositionality finding on the "need for effective remedy" with the same prominence as some later Supreme Court cases (such as the 2008 ruling on land readjustment plans), the act of recognizing the customs notification as a reviewable administrative disposition inherently provides importers with a direct legal path to challenge the customs authorities' determination in court. This is consistent with a broader judicial trend towards ensuring that citizens have meaningful access to justice when their rights are affected by administrative actions.

Conclusion

The 1984 Supreme Court Grand Bench decision in the import-prohibited goods case is a landmark ruling with several important dimensions. It robustly affirmed the customs authorities' power to restrict the import of obscene materials, finding this to be a constitutionally permissible measure to protect public morals, even when it impacts freedom of expression and the right to access information. The Court also provided a detailed constitutional analysis distinguishing customs inspection from prohibited censorship.

From an administrative law perspective, the decision solidified the principle that a customs notification deeming goods as import-prohibited functions as a final administrative refusal and thus constitutes a reviewable "administrative disposition." This ensures that importers whose goods are blocked at the border have a direct avenue to seek judicial review of the customs authorities' judgment, thereby upholding the rule of law in this critical area of state power. The case remains a vital reference for understanding the interplay between international trade, constitutional rights, and administrative procedure in Japan.