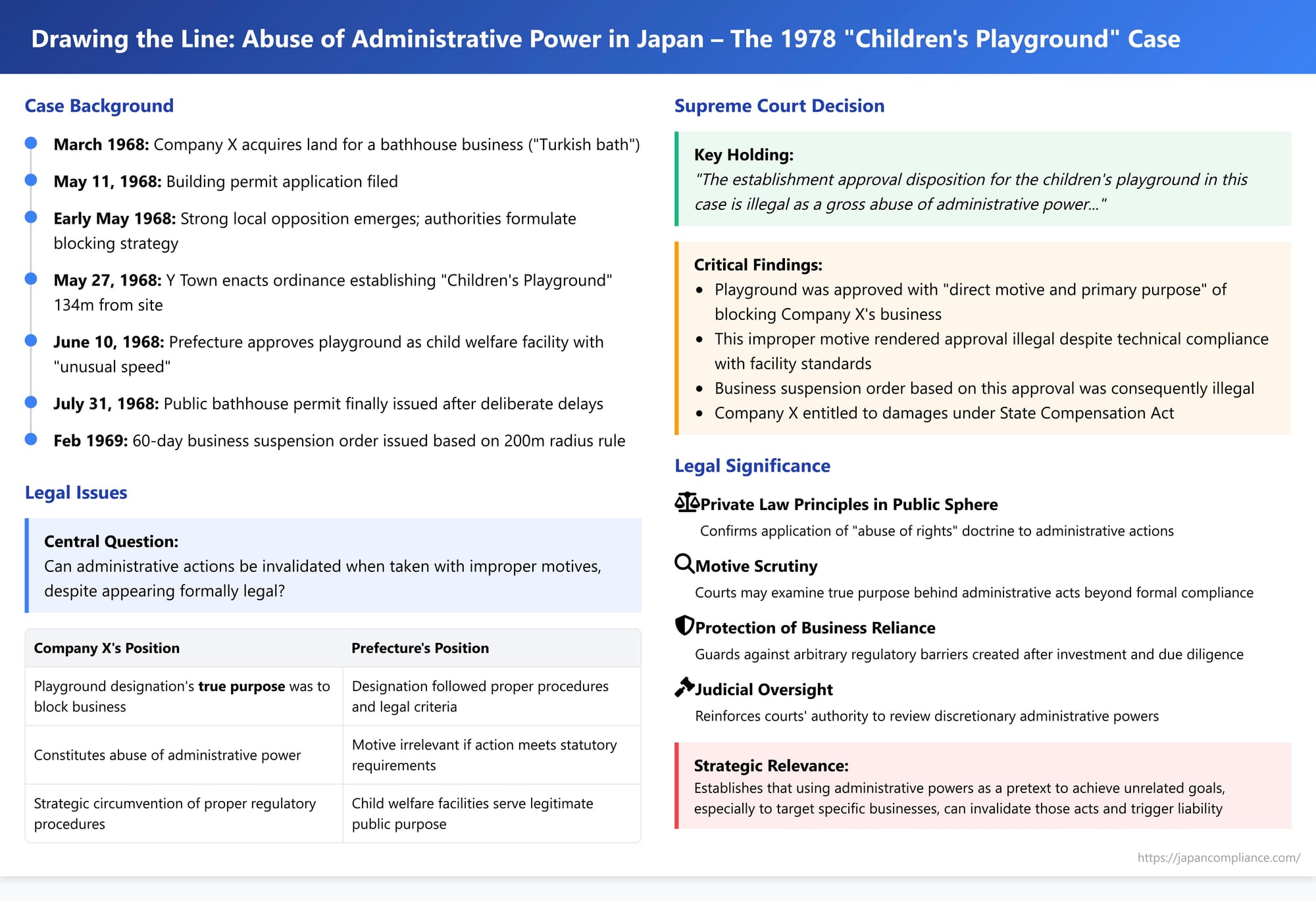

Drawing the Line: Abuse of Administrative Power in Japan – The 1978 "Children's Playground" Case

Administrative bodies are vested with significant powers to regulate society and implement public policy. However, these powers are not absolute and must be exercised within the bounds of the law and for their intended purposes. A landmark judgment by the Supreme Court of Japan on May 26, 1978, serves as a critical reminder that when administrative actions are driven by improper motives and result in the misuse of legal tools, they can be deemed an illegal "abuse of administrative power" (gyōseiken no ran'yō).

The Factual Background: A Controversial Business Plan Meets Determined Opposition

The case centered on the efforts of Company X, represented by Mr. A, to establish a bathhouse business with private rooms (a type of establishment then commonly known as "Turkish baths," though this term is now considered offensive) in Y Town, Yamagata Prefecture[cite: 1, 2].

- Initial Steps and Due Diligence: Mr. A planned to open this business and, after investigating the existing regulations under the Public Morals Business Control Law (the "Old Fūei Hō," Fūzoku Eigyō-tō Torishimari Hō), acquired land for construction around March 1968[cite: 1, 2]. On May 11, 1968, Mr. A, in his personal capacity, applied for a building permit for the business premises and also applied for a public bathhouse business permit (this latter application was later withdrawn and re-filed in Company X's name on June 6, 1968)[cite: 1, 2].

- Local Opposition and Official Intervention: By early May 1968, strong local opposition to the proposed bathhouse emerged[cite: 1, 2]. In response, the government of Yamagata Prefecture (Y, the defendant) and Y Town authorities formulated a strategy to prevent the business from opening[cite: 1, 2].

- The "Alternative Plan" to Block the Business:

- The authorities initially considered amending a prefectural ordinance under the Old Fūei Hō to designate the area as a prohibited zone for such businesses. However, this approach was deemed too slow due to the schedule of the prefectural assembly[cite: 1, 2].

- A more expedient, albeit indirect, plan was devised, reportedly at the strong urging of the prefectural police headquarters[cite: 1]. This plan involved quickly designating a nearby children's playground (jidō yūen)—located on the site of a former school approximately 134 meters from Company X's proposed construction site—as an official "child welfare facility" under Japan's Children's Welfare Act (Jidō Fukushi Hō)[cite: 1, 2].

- The significance of this designation was that Article 4-4, Paragraph 1 of the Old Fūei Hō prohibited the operation of businesses like Company X's establishment within a 200-meter radius of specified facilities, including schools, libraries, and, crucially, child welfare facilities established under the Children's Welfare Act[cite: 1, 2].

- Rapid Implementation: This alternative strategy was executed with notable speed:

- On May 27, 1968, the Y Town council enacted an ordinance to formally establish the "Y Town Children's Playground" and immediately applied to the Governor of Yamagata Prefecture for its approval as a child welfare facility[cite: 1, 2].

- On June 10, 1968, the Prefectural Governor granted this approval with what was described as "unusual speed" (irei no hayasa)[cite: 1, 2]. This approval is referred to as the "Establishment Approval" (setchi ninka).

- Company X's Progress and Subsequent Obstacles:

- Meanwhile, Mr. A had received his building permit on May 23, 1968, and commenced construction of the bathhouse[cite: 1, 2]. By the end of June, the building was substantially completed, and an inspection certificate was issued on July 11, 1968[cite: 1, 2].

- However, the public bathhouse business permit for Company X faced delays. It was not issued until July 31, 1968, allegedly because the prefectural environmental hygiene section, at the request of the prefectural police, held back the permit's issuance[cite: 1, 2].

- Business Operation, Suspension, and Legal Action: Company X eventually began operating the bathhouse around September 1968. In February 1969, the Prefectural Public Safety Commission issued a 60-day business suspension order against Company X[cite: 1, 2]. Company X was also subjected to criminal prosecution for violating the Old Fūei Hō (due to its proximity to the newly designated child welfare facility)[cite: 1, 2].

- Company X initially filed a suit to revoke the business suspension order. However, as the suspension period elapsed while the lawsuit was pending, the company amended its claim to seek monetary damages from Yamagata Prefecture under Article 1 of the State Compensation Act (Kokka Baishō Hō). The core of Company X's argument was that the Establishment Approval for the children's playground was granted solely for the improper purpose of blocking its legitimate business operations. As such, X contended, the approval constituted an abuse of administrative power, rendering it legally invalid. Consequently, the business suspension order, which was predicated on the existence of this "unlawfully" established child welfare facility, was also illegal and invalid, leading to compensable damages[cite: 1, 2].

Lower Courts' Differing Views

The lower courts had conflicting opinions on the matter:

- The Yamagata District Court (first instance) dismissed Company X's claim for damages, siding with the prefectural authorities.

- The Sendai High Court (second instance), however, reversed this decision and ruled in favor of Company X. The High Court acknowledged that, objectively viewed in isolation, the children's playground itself might have met the minimum physical standards for a child welfare facility, and thus the Establishment Approval might not appear intrinsically illegal on its face. However, the High Court found it "clear that the Establishment Approval was made with the direct motive and primary purpose of blocking and prohibiting" Company X's bathhouse business. It concluded that this motivation rendered the approval a "gross abuse of administrative power" (gyōseiken no ichijirushii ran'yō) and therefore illegal[cite: 1, 2].

Yamagata Prefecture appealed the High Court's ruling to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Affirming "Abuse of Power"

In a notably concise judgment issued on May 26, 1978, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court dismissed Yamagata Prefecture's appeal, thereby upholding the Sendai High Court's decision in favor of Company X[cite: 2].

The Supreme Court stated:

"Under the facts found by the court below [the Sendai High Court], the establishment approval disposition for the children's playground in this case is illegal as a gross abuse of administrative power, and it is reasonable to find a considerable causal relationship between the said approval disposition and the damages suffered by the appellee (Company X) due to the business suspension order predicated thereon. Therefore, the appellee's claim for damages in this suit should be accepted." [cite: 2]

The Supreme Court explicitly affirmed the High Court's finding that the approval of the children's playground as a child welfare facility, given the circumstances and motivations, constituted a "gross abuse of administrative power" and was therefore illegal[cite: 2].

Analysis and Implications: When Administrative Actions Cross the Line

This 1978 Supreme Court decision is a cornerstone in Japanese administrative law concerning the abuse of power. Its implications are manifold:

- Doctrine of Abuse of Right/Power in Public Law: The legal commentary accompanying the case highlights that general principles of private law, such as the prohibition of the abuse of rights (codified in Article 1, Paragraph 3 of the Civil Code), are understood to be applicable to administrative actions and legal relationships[cite: 1]. This Supreme Court judgment is a leading example confirming this applicability in the context of administrative power.

- Improper Motive as the Core of Abuse: The decisive factor in this case was the improper motive behind the administrative action. The authorities utilized their power to approve child welfare facilities not for the genuine statutory purpose of promoting children's welfare, but for the ulterior purpose of shutting down an unwanted business. The High Court had determined that this intent to block Company X was the "direct motive and primary purpose" of the Establishment Approval[cite: 1]. This aligns with theories of administrative discretion where actions driven by legally irrelevant considerations or for purposes alien to the empowering statute can be deemed an abuse.

- "Appearance of Legality" Is Not Sufficient: The case demonstrates that even if an administrative act (like the approval of the playground) appears to satisfy formal or superficial legal requirements (e.g., the playground met minimum physical standards for such a facility), it can still be invalidated as an abuse of power if its true, underlying purpose is found to be illegitimate or extraneous to the objectives of the empowering law[cite: 1].

- Circumvention of Proper Legal Procedures: The authorities had initially contemplated a more direct, albeit slower, method for restricting Company X's business – amending a prefectural ordinance to create a specific prohibited zone. Their subsequent resort to the child welfare facility designation was seen as a strategic maneuver to achieve their aim more rapidly by leveraging a different legal instrument for a purpose it was not designed for[cite: 1]. The commentary suggests that using a regulatory method not envisioned by the law for that specific type of business restriction (i.e., using child welfare facility status rather than specific zoning or public morals ordinances) was a contributing factor to the finding of abuse[cite: 1].

- Impact on Legitimate Business Reliance: Mr. A, on behalf of Company X, had undertaken due diligence by checking the existing regulations and had made significant financial investments in acquiring land and commencing construction before the authorities initiated their "emergency" actions to block the project[cite: 1]. The rapidly implemented regulatory barrier, created through the swift designation of the playground, effectively nullified these investments and frustrated legitimate business expectations. The fact that Company X had proceeded after confirming the existing legal framework was an important background element[cite: 1].

- Judicial Scrutiny of Administrative Discretion: This judgment powerfully underscores that discretionary powers granted to administrative bodies are not unfettered. Courts retain the authority to review the exercise of such discretion and will intervene if it is found to be manifestly unreasonable, based on improper motives, or for purposes contrary to the empowering legislation.

- The "Race Against Time" Element: The timing of the administrative actions was a critical aspect. The authorities demonstrably rushed the approval of the children's playground to create a prohibitive factual and legal situation before Company X could legally commence its operations. The legal commentary notes that the Old Fūei Hō contained an exemption for businesses already holding a public bathhouse permit at the time a new prohibited zone was established around them. Company X was effectively caught in a "race," with its own application for a public bathhouse permit being deliberately delayed while the prohibitive playground designation was expedited[cite: 1].

- Precursor to "Duty of Consideration" Principles: Although the term "duty of consideration" (hairyo gimu) was more explicitly developed in later Supreme Court cases (such as the Kii-Nagashima water source protection ordinance case also discussed in this series), the 1978 "Children's Playground" judgment can be viewed, as the commentary suggests, as an early judicial expression of concern for protecting legitimate business reliance against arbitrary or improperly motivated administrative actions that disrupt established expectations without due process[cite: 1].

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1978 ruling in the "Children's Playground" case stands as a significant precedent in Japanese law, affirming that administrative power, even when cloaked in the guise of formal legality, can be deemed an illegal "abuse" if its predominant purpose is found to be improper and unrelated to the objectives of the law under which that power is exercised.

This decision serves as a crucial safeguard against arbitrary governance, sending a clear message that using administrative powers as a pretext to achieve unrelated goals, particularly to target specific individuals or businesses in a manner that undermines their legitimate reliance and investment, can lead to the invalidation of those administrative acts and potentially to liability for damages under the State Compensation Act. It highlights the judiciary's vital role in policing the boundaries of administrative discretion and ensuring that public power is wielded responsibly and in good faith.