Drawing Procedural Lines: Scope of Challenge in an "Action of Objection to the Grant of a Writ of Execution" in Japan

In the Japanese civil execution system, obtaining a "writ of execution" (執行文 - shikkōbun) from a court clerk is a critical step before a creditor can forcibly enforce a judgment or other "title of obligation" (債務名義 - saimu meigi). While usually an administrative process, if a debtor believes this writ has been improperly issued—for instance, because a condition for execution stipulated in the judgment has not actually been met, or because the writ has been issued against an incorrect successor to the original debtor—they can file a specific type of lawsuit known as an "action of objection to the grant of a writ of execution" (執行文付与に対する異議の訴え - shikkōbun fuyo ni taisuru igi no uttae) under Article 34 of the Civil Execution Act (formerly Article 546 of the Code of Civil Procedure).

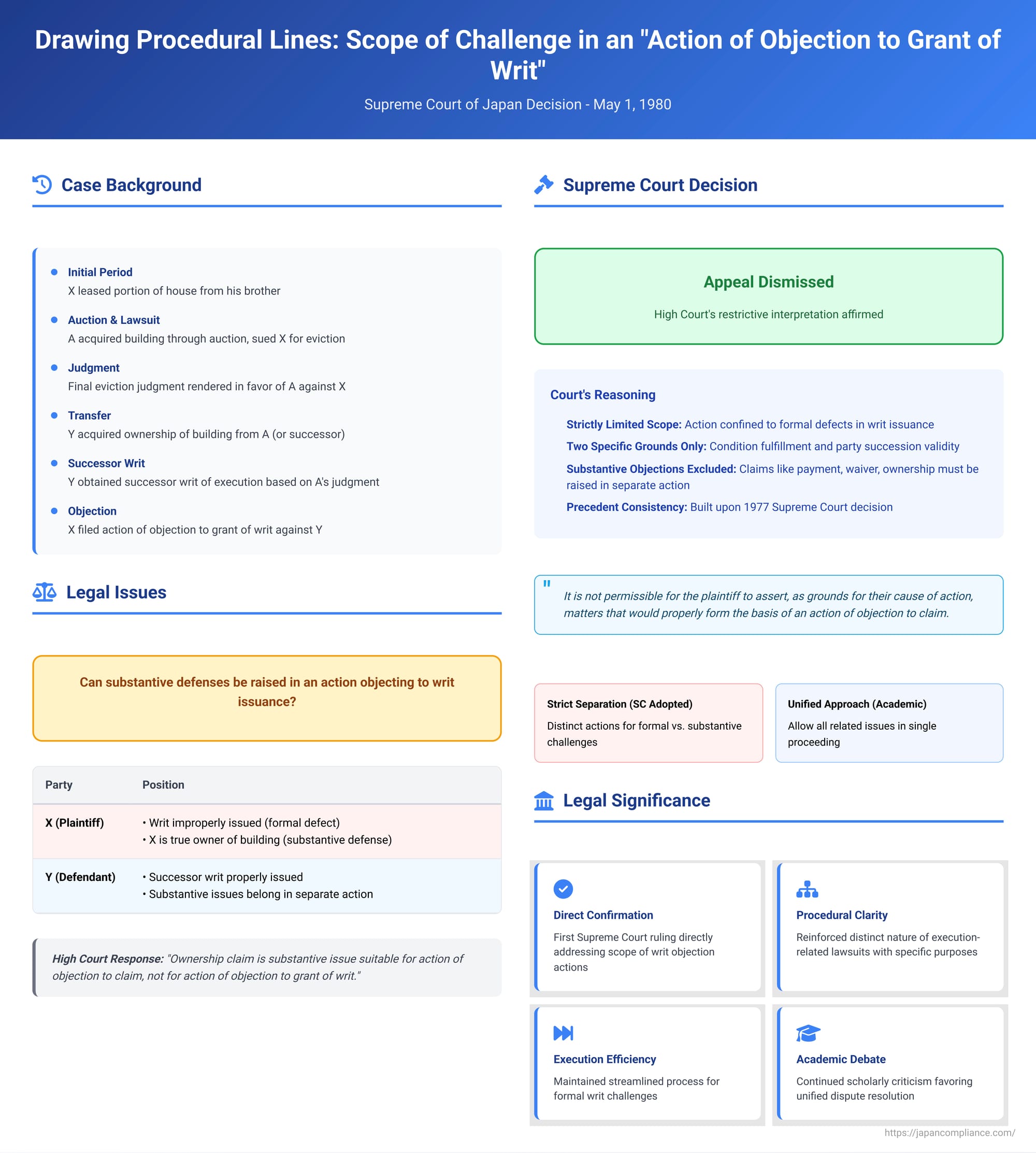

A fundamental procedural question concerns the scope of arguments that the plaintiff (typically the judgment debtor or their successor) can raise in such an action. Can they go beyond challenging the formal propriety of the writ's issuance and also assert substantive reasons why the underlying claim itself should not be enforced (e.g., because the debt has been paid or waived)? A 1980 Supreme Court of Japan decision directly addressed this, reaffirming a strict interpretation of the distinct roles of different execution-related lawsuits.

Background of the Dispute

The plaintiff, Mr. X, occupied a portion of a house he had leased from his brother. Some time prior, a third party, A (not a party to the immediate Supreme Court case), had acquired the entire building through an auction. A then initiated an eviction lawsuit against Mr. X concerning the portion X occupied. A judgment was rendered in A's favor, ordering X's eviction, and this judgment became final and binding.

Subsequently, Mr. Y acquired ownership of the building (presumably from A or A's successor in interest). Based on the original eviction judgment obtained by A against X, Mr. Y obtained a "successor writ of execution." This type of writ allows a judgment to be enforced by or against a successor to the original parties. In this instance, the writ apparently positioned Y as the successor to A's rights as the judgment creditor, and enabled Y to enforce the eviction against X.

Mr. X challenged this by filing an "action of objection to the grant of a writ of execution" against Mr. Y. His primary argument in this lawsuit was that the successor writ had been improperly issued because Y was not a legitimate successor to A's rights under the original judgment, or that X was not a successor to the original judgment debtor in a manner that justified enforcement by Y.

During the appeal stage of this writ objection lawsuit, Mr. X sought to introduce an additional, crucial argument: he claimed that he, Mr. X, was in fact the true owner of the building, and therefore, any compulsory execution (eviction) by Mr. Y against him was impermissible. This claim of ownership is a substantive defense going to the merits of whether Y had any right to evict X, rather than a purely formal defect in the issuance of the writ.

The Osaka District Court (court of first instance) had earlier ruled against Mr. X, finding Y's acquisition of ownership (and thus Y's status as a successor entitled to the writ) to be valid, and dismissed X's objection to the writ.

The Osaka High Court (appellate court) also dismissed Mr. X's appeal. Regarding Mr. X's newly emphasized claim of ownership, the High Court held that this was a substantive issue. While it might potentially serve as a ground for an "action of objection to claim" (請求異議の訴え - seikyū igi no uttae)—a separate lawsuit where a debtor challenges the enforceability of the underlying claim itself—it was not a permissible ground for challenging the grant of a successor writ of execution within the specific framework of an "action of objection to the grant of a writ of execution." The High Court reasoned that the latter type of action is confined to addressing formal issues such as the fulfillment of a condition precedent for execution or the factual validity of a party's succession.

Mr. X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of Japan. He argued, among other points, that when a court is tasked with determining the existence of executory force through a full judicial proceeding (like the action of objection to the writ), there is no longer a compelling need to rigidly separate formal grounds for objection from more fundamental substantive grounds. He contended that forcing parties into multiple, stylized lawsuits for different aspects of the same underlying dispute is contrary to litigation economy.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court of Japan dismissed Mr. X's appeal, thereby affirming the High Court's restrictive interpretation of the scope of an "action of objection to the grant of a writ of execution."

The Court's reasoning was concise and directly built upon its recent precedent:

- Strictly Limited Scope of Adjudication: The Supreme Court reiterated that the scope of matters to be審理 (adjudicated) in an "action of objection to the grant of a writ of execution" (under old Code of Civil Procedure Article 546, now Civil Execution Act Article 34) is strictly limited to:

- Determining whether a condition upon which the enforceability of the title of obligation depends has, in fact, been fulfilled (in cases where a writ was issued based on such condition).

- Determining whether a succession of parties (concerning the title of obligation) has, in fact, occurred (in cases where a successor writ of execution was issued).

- Substantive Objections Not Permissible as Grounds for This Action: Consequently, the Court held that it is not permissible for the plaintiff in such an action (the debtor or successor objecting to the writ) to assert, as the grounds for their cause of action, matters that would properly form the basis of an "action of objection to claim" (under old CCP Article 545, now Civil Execution Act Article 35). These latter grounds typically relate to substantive reasons why the underlying claim should no longer be enforced (e.g., payment, set-off, waiver, prescription that occurred after the title of obligation was formed).

- Reliance on the 1977 Precedent: The Supreme Court explicitly stated that this conclusion was "evident from the purport of the precedents of this Court," specifically citing its First Petty Bench decision of November 24, 1977 (Showa 51 (O) No. 1202). That 1977 case had held that in an "action for the grant of a writ of execution" (where the creditor is the plaintiff seeking the writ), the defendant debtor cannot raise substantive objections to the claim as mere defenses within that action. This 1980 ruling extended that logic to the reciprocal situation where the debtor is the plaintiff objecting to a writ already granted.

The Supreme Court therefore found the High Court's judgment, which similarly confined the scope of X's action, to be correct and upheld it.

Significance and Analysis of the Decision

This 1980 Supreme Court judgment, while perhaps predictable in light of its 1977 predecessor, served to solidify the Court's stance on the strict compartmentalization of grounds for different types of execution-related lawsuits in Japan.

- Direct Confirmation for Writ Objection Suits: As the PDF commentary points out, this was the Supreme Court's first direct ruling confirming that grounds properly belonging to an "action of objection to claim" cannot be used by the plaintiff as the basis for an "action of objection to the grant of a writ of execution".

- Consistent Jurisprudence Favoring "Action-Type Specificity": This decision is part of a consistent line of Supreme Court jurisprudence, particularly from the 1960s and 1970s, that increasingly emphasized the distinct nature and purpose of various execution-related lawsuits. These rulings generally support the "theory of concurrent actions" or "action-type specificity theory" (訴権競合説 - soken kyōgō setsu). This theory posits that lawsuits like the "action of objection to claim" and the "action of objection to the grant of a writ" are independent actions, each with its own specific, non-interchangeable grounds for relief.

- A 1966 Supreme Court case had already distinguished between grounds for objecting to a writ and grounds for objecting to a claim in the context of default clauses in settlement agreements.

- A 1968 Supreme Court case explicitly stated that an "action of objection to claim" and an "action of objection to the grant of a writ" are "separate actions with different objectives".

- The crucial 1977 Supreme Court case then barred defendants from raising substantive objections as mere defenses in an action for the grant of a writ.

- Furthermore, a later Supreme Court decision in December 1980 (Showa 55.12.9) held that a party's failure to raise a substantive objection in a prior action of objection to a writ does not preclude them from raising that same substantive ground in a subsequent action of objection to claim. This lack of issue preclusion for substantive grounds across these different procedural avenues further underscores their distinct nature under this theory.

- Alternative Academic Theories: The PDF commentary details the ongoing academic debate, contrasting the Supreme Court's "action-type specificity" approach with other theories:These theories diverge based on their interpretation of legislative intent, the value placed on procedural efficiency versus formal distinctions, and the perceived fairness of issue preclusion in this context.

- Theory of Subsumption/Statutory Joinder (法条競合説 - hōjō kyōgō setsu): This view sees both types of actions (writ objection and claim objection) as fundamentally similar in their ultimate goal of determining the propriety of execution. It argues that grounds for both should be litigable in a single suit. A key implication often associated with this theory is that if a ground could have been raised in the first action (e.g., a writ objection suit that allows substantive claims), it would be precluded from being raised in a later action (e.g., a claim objection suit).

- Eclectic/Intermediate Theory (折衷説 - setchū setsu): This theory shares with the subsumption theory the idea that the ultimate aim of these actions is similar and that grounds should ideally be intermingled for efficiency. However, it acknowledges that the law does provide for two distinct forms of action. Therefore, while it might allow the mixing of grounds, it would argue against issue preclusion if a party chose to use one form of action and did not raise all possible grounds; they should be allowed to raise the omitted grounds in the other form of action later.

- Critique of the Supreme Court's Approach: The author of the PDF commentary is critical of the Supreme Court's strict separation, similar to the critique offered for the 1977 decision. The main arguments for allowing a more unified approach (i.e., permitting substantive defenses within writ-related actions) include:

- Efficiency and One-Stop Resolution: Addressing all related issues in a single proceeding could be more efficient and better serve the goal of comprehensively resolving the dispute between the parties.

- Avoiding Formalism: Forcing parties into separate, rigidly defined lawsuits for different types of objections can appear overly formalistic and burdensome, especially when the underlying goal is simply to determine if execution should proceed.

- Potential for Inconsistent Outcomes or Complex Reconciliations: The PDF commentary on the 1977 case (which is relevant here due to the similar reasoning) pointed out potential awkwardness if, for example, a debtor could win both an action objecting to a writ (on formal grounds) and a separate action objecting to the claim (on substantive grounds), leading to questions about how these judgments would interact if rendered simultaneously.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's May 1, 1980 decision firmly reinforced the principle that an "action of objection to the grant of a writ of execution" in Japan has a narrowly defined scope. It is a procedural tool focused on formal defects in the issuance of the writ, specifically concerning the fulfillment of conditions for execution or the validity of party succession. Debtors or their successors cannot use this particular lawsuit to raise substantive challenges to the underlying enforceability of the claim itself; such objections must be pursued through a distinct "action of objection to claim."

This ruling, consistent with the Court's 1977 precedent, underscores a judicial policy of maintaining clear procedural lines between different types of execution-related remedies. While this approach emphasizes formal correctness and the distinct purposes of each statutory action, it remains a subject of academic discussion regarding its overall impact on litigation economy and the comprehensive resolution of disputes arising in the context of civil execution.