Double Payments and Missed Notices: Navigating Reimbursement Among Joint Debtors in Japan

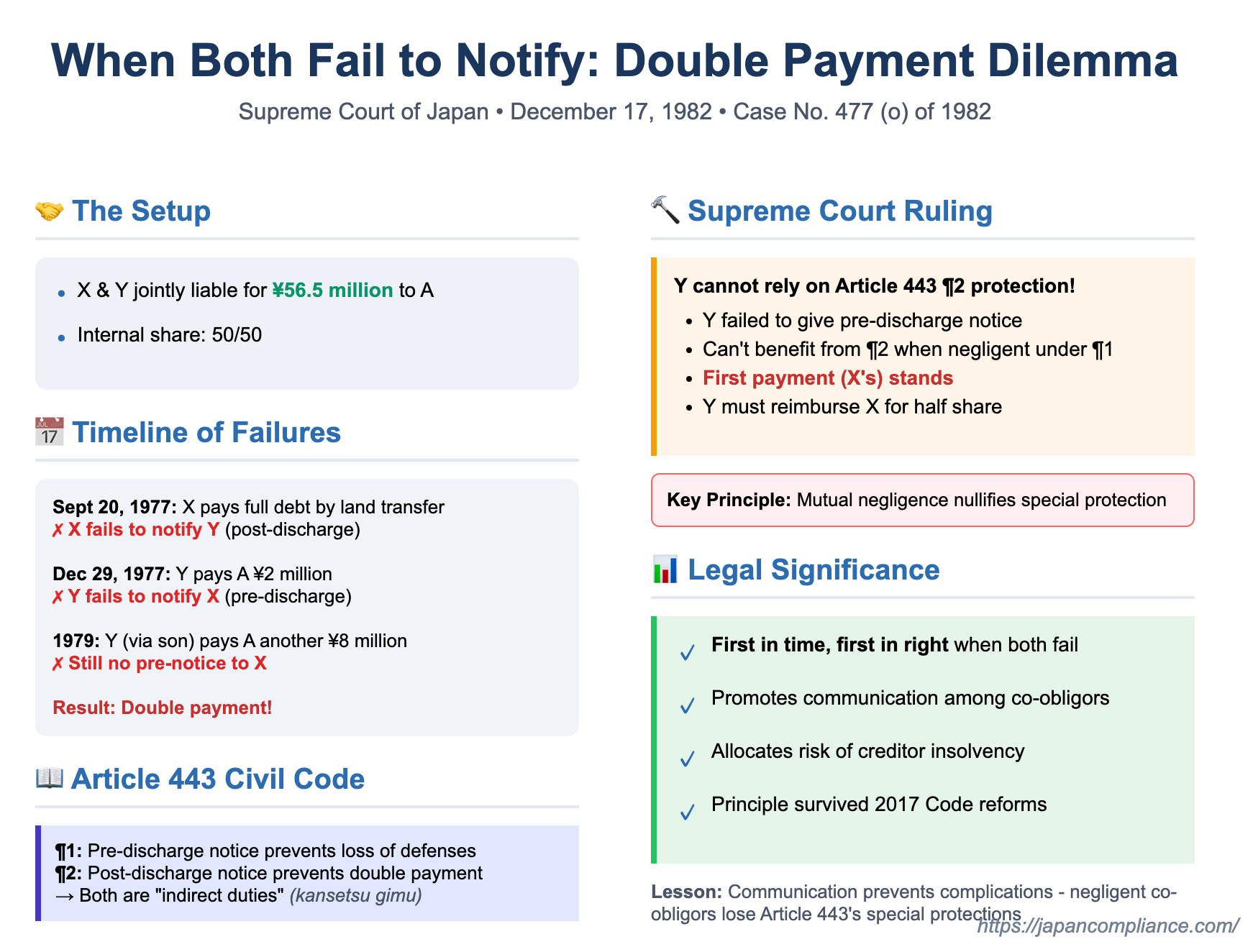

When multiple parties are jointly and severally liable for a single debt, each is responsible for the full amount to the creditor, but internally, they usually share the burden. If one obligor pays more than their share, they can seek reimbursement (kyūshō) from the others. However, Japanese law (specifically Article 443 of the Civil Code) encourages communication between these co-obligors to prevent complications like double payments. A Supreme Court of Japan decision on December 17, 1982 (Showa 56 (O) No. 477) provided crucial clarity on what happens when this communication breaks down on multiple fronts.

Joint and Several Liability and the "Indirect Duty" of Notice (Article 443)

Under joint and several liability (rentai saimu), a creditor can demand full payment from any one of the obligors. Once an obligor pays the debt (or part of it exceeding their internal share), they generally gain a right to be reimbursed by the other co-obligors for their respective shares.

To avoid situations where, for instance, one obligor pays the debt, and then another, unaware of this payment, also pays the same creditor (a "double payment"), Article 443 of the Civil Code outlines a system of notifications:

- Pre-Discharge Notice (Paragraph 1): An obligor intending to discharge the debt (e.g., by payment or set-off) should notify the other co-obligors beforehand. If they fail to do so and another co-obligor had a valid defense against the creditor (which is now lost because the debt is paid), the paying obligor's reimbursement claim against that co-obligor might be restricted.

- Post-Discharge Notice (Paragraph 2): An obligor who has discharged the debt should notify the others afterward. If they fail to do so, and another co-obligor, acting in good faith and without knowledge of the prior discharge, subsequently makes a payment or otherwise discharges the debt, this second discharge is considered effective for the purpose of that second obligor seeking reimbursement from the first (negligent) obligor.

These notices are not strict legal obligations for the reimbursement right to arise but are termed "indirect duties". Failure to provide them doesn't void the reimbursement right itself but can lead to limitations or penalties, effectively incentivizing communication. The core problem addressed by the 1982 Supreme Court case is: what if both the first obligor to pay fails to give post-discharge notice, and a second obligor who subsequently pays also fails to give pre-discharge notice?

Facts of the 1982 Case (X v. Y)

The dispute involved two individuals, X and Y, who were jointly and severally liable to a creditor, A, for 56.5 million yen, with their internal burden-sharing being equal.

- X's Discharge: On September 20, 1977, X discharged the entire debt by transferring land to A (a "substitute performance" or daibutsu bensai). However, X failed to notify Y of this discharge afterwards (no post-discharge notice).

- A's (Mis)understanding: Creditor A apparently mistakenly believed that X's land transfer was only a partial payment for a different debt X owed, not the joint and several debt. Consequently, A continued to demand payment from Y for the joint debt.

- Y's Payments: Unaware that X had already settled the entire debt, Y made payments to A:

- On December 29, 1977, Y paid A 2 million yen. Y did not notify X before making this payment.

- Later, Y's son, C (acting for Y due to Y's illness), negotiated with A and, on May 31, 1979, assumed 8 million yen of the debt, paying 4 million yen that day and another 4 million yen on September 29, 1979. The appellate court treated C's actions as Y's. C also did not give X pre-notice, though the appellate court found C not negligent in this as X's whereabouts were allegedly unknown at that time.

- Double Payment and Lawsuit: This series of events led to a double payment of a portion of the debt. X eventually sued Y for Y's half-share (28.25 million yen) of the original debt that X had discharged. The central issue became how these overlapping payments and mutual failures to notify should be resolved under Article 443.

The Supreme Court's Ruling: No Protection for the Negligent Second Payer

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, effectively upholding the first payment made by X as the valid discharge of the original debt.

The Court's core finding was:

If a joint and several obligor (like Y, the second payer in this scenario) fails to give notice to another co-obligor (like X, the first payer) before undertaking their own act of discharging the debt, they cannot then rely on Article 443, Paragraph 2 to have their own discharge act deemed effective for reimbursement purposes against the first obligor, even if that first obligor had already discharged the debt but failed to give the required post-discharge notice.

The reasoning was that Article 443, Paragraph 2—which protects a second payer who acts in good faith when the first payer omits post-discharge notice—is predicated on the general framework of Article 443, including Paragraph 1 (which deals with the consequences of failing to give pre-discharge notice). The Court stated that Paragraph 2 is not intended to protect a co-obligor who was themselves negligent in failing to give the pre-discharge notice encouraged by Paragraph 1. In other words, the special protection afforded to a second payer under Paragraph 2 assumes that the second payer was otherwise diligent and not at fault regarding their own notification duties.

Unpacking the Decision: Prioritizing the First Discharge in Cases of Mutual Negligence

This 1982 ruling was significant because it provided a clear answer from Japan's highest court to a situation not explicitly detailed in the Civil Code, reinforcing what had become the dominant scholarly view.

- First in Time, First in Right (Generally): When both obligors are at fault in their notification duties—the first by not giving post-discharge notice and the second by not giving pre-discharge notice—the general principle is that the discharge which occurred first in time is the one that legally extinguishes the debt to the creditor.

- The "Indirect Duty" and "Negligence": While Article 443 doesn't frame notification as a strict, absolute duty, the failure to notify is treated as a form of "negligence" or lapse that can lead to disadvantageous consequences, such as limitations on the right of reimbursement.

- The Dual Function of Pre-Notice: Legal scholars have pointed out that pre-discharge notice by a paying obligor serves two functions. Primarily, it allows other co-obligors to raise any defenses they might have against the creditor (e.g., a right of set-off) before the debt is paid. Secondarily, it acts as an inquiry or a warning to other co-obligors that a discharge is about to happen, which can help prevent them from mistakenly making a second payment. A second payer who fails to give pre-notice can be seen as failing in this secondary, preventative function.

- Symmetrical Fault Nullifies Special Protection: If the first payer fails to prevent potential double payment by omitting post-discharge notice, and the second payer also contributes to the risk by omitting pre-discharge notice (thus failing to inquire or warn), then both are, in a sense, at fault regarding the double payment. In such a scenario of mutual lapse, the special provision of Article 443, Paragraph 2 (which deems the second payment effective for reimbursement purposes against the first payer) should not benefit the second payer. The initial discharge by X stands as the effective one.

Theoretical Evolution and the Purpose of Article 443

The 1982 Supreme Court decision, though its reasoning was concise, spurred further academic discussion about the deeper purposes of Article 443.

- Some scholars argue that Article 443 implicitly recognizes a good faith duty among co-obligors to communicate and take reasonable steps to prevent double payments.

- A significant theoretical development has been the view that Article 443 is, at its core, about allocating the risk of the creditor's insolvency. If a double payment occurs, and the overpaid creditor becomes insolvent and cannot return the excess, which obligor bears that loss? The rules in Article 443, by restricting reimbursement rights based on notification failures, effectively place this risk on the obligor deemed more "at fault" due to their failure to notify. If both are at fault, some newer theories propose that this insolvency risk should be shared equitably between them, perhaps according to their internal burden-sharing ratios.

- There are also emerging views that emphasize a "duty to investigate prior acts" for any obligor intending to discharge the debt, rooting this in the pre-notice requirement and a stringent interpretation of "good faith".

Relevance in Light of the 2017 Civil Code Reforms

The principles established by the 1982 Supreme Court judgment largely retain their significance even after the major 2017 reforms to the Japanese Civil Code's law of obligations. While Article 443 underwent some consideration for substantial changes during the reform process—including proposals to make pre-notice entirely optional or to codify the 1982 ruling's outcome explicitly—these major alterations were ultimately not adopted.

Minor textual changes were made to Article 443 in 2017:

- The content of the pre-notice was clarified: from notifying that "a demand for performance has been received" to notifying that one "will obtain a joint discharge". This reflected existing scholarly understanding.

- The qualifier "negligent" was removed when describing an obligor who obtained discharge without pre-notice, as the failure itself often implies negligence.

These minor changes are unlikely to affect the standing or interpretation of the 1982 decision.

One notable addition was the phrase "knowing that there are other joint obligors" into both paragraphs of Article 443. This clarifies that notice is not required towards co-obligors whose existence is unknown to the paying obligor. The commentary suggests this "knowing" element might be interpreted with some flexibility, as seen in the appellate court's handling of C's non-notice to X in this very case, where X's whereabouts were unknown.

Conclusion: Communication is Key

The Supreme Court's 1982 decision delivers a clear message for joint and several obligors: communication is crucial. In situations of mutual failure to provide the notices encouraged by Article 443 of the Civil Code, the law will generally uphold the first valid discharge of the debt. A second obligor who also failed in their duty to give pre-discharge notice cannot invoke the special protections of Article 443, Paragraph 2 to have their subsequent payment deemed effective against the first payer for reimbursement purposes. This judgment emphasizes that the provisions designed to protect diligent co-obligors from the consequences of another's notification lapse are not available to those who were similarly remiss in their own communication duties, thereby promoting fairness and helping to prevent the complications arising from double payments.