Double Jeopardy in Juvenile Court: Japan Supreme Court Defines Scope of Protection After Protective Disposition (September 20, 1961 Decision)

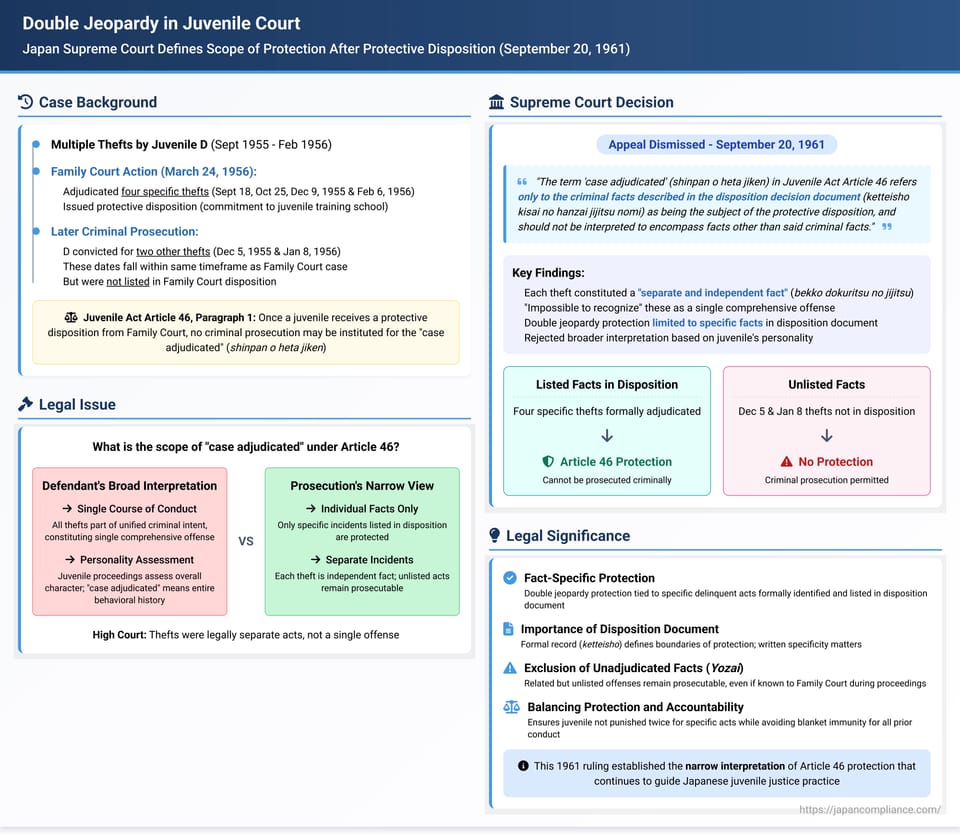

The principle against double jeopardy – that an individual should not be tried or punished twice for the same offense – is a cornerstone of criminal justice systems worldwide, including Japan's (Constitution Article 39). Japan's Juvenile Act, which governs proceedings for minors who commit offenses, contains a specific provision reflecting this principle. Article 46, Paragraph 1 states that once a juvenile who has committed an act that would be a crime if committed by an adult receives a "protective disposition" (hogo shobun) from the Family Court (such as commitment to a juvenile training school or placement on probation), no criminal prosecution may be instituted for the "case adjudicated" (shinpan o heta jiken).

This provision seems straightforward, but a critical question arises: What exactly constitutes the "case adjudicated" by the Family Court? Does the protection extend only to the specific delinquent acts formally identified and listed as the basis for the protective disposition? Or could it encompass other related offenses committed around the same time, perhaps as part of a single course of conduct, even if not explicitly mentioned in the Family Court's final order? Furthermore, some argued historically that because juvenile proceedings focus on the child's overall character and need for rehabilitative measures (yō-hogo-sei), perhaps the "case adjudicated" should refer to the juvenile's entire personality and past conduct up to that point, effectively barring prosecution for any prior acts. The Supreme Court of Japan provided a definitive answer to the scope of Article 46 protection in a ruling dated September 20, 1961.

Case Background: Serial Thefts, Protective Disposition, and Later Prosecution

The case involved defendant D, who had committed a series of thefts. Some of these thefts occurred while D was still legally a juvenile.

- Family Court Action: D was apprehended as a juvenile for suspected thefts. On March 24, 1956, the Sendai Family Court (Furukawa Branch) determined D had committed four specific theft incidents (occurring on Sept 18, 1955; Oct 25, 1955; Dec 9, 1955; and Feb 6, 1956). Based on these findings, the Family Court issued a protective disposition, committing D to an intermediate juvenile training school.

- Criminal Prosecution: Later, after D had become an adult, D was criminally prosecuted and convicted for several thefts. Among these convictions were sentences for two other thefts that D had committed on December 5, 1955, and January 8, 1956 – dates falling within the same general timeframe as the thefts handled by the Family Court, but not among the four specific incidents listed in the Family Court's disposition order.

The Double Jeopardy Challenge

D appealed the criminal conviction, specifically challenging the guilty verdict for the December 5th and January 8th thefts. The core legal argument rested on Juvenile Act Article 46 and the principle against double jeopardy:

- Single Course of Conduct Argument: D argued that all the thefts committed between September 1955 and February 1956, including the two prosecuted criminally, were part of a single, continuous course of conduct driven by a unified criminal intent (tan'itsu han'i). Therefore, they should legally constitute a single comprehensive offense (hōkatsuteki ichizai). Since the Family Court had already adjudicated and issued a disposition for part of this single offense (the four listed thefts), Article 46 should bar subsequent prosecution for other parts of the same alleged offense (the December 5th and January 8th thefts).

- Adjudication of Personality Argument: Alternatively, D argued that juvenile proceedings fundamentally assess the juvenile's overall personality and need for protection, not just isolated acts. Therefore, the phrase "case adjudicated" in Article 46 should be interpreted broadly to mean the juvenile's entire character and behavioral history up to the point of the Family Court's disposition. If so, any delinquent act committed before the protective disposition should be covered by the bar against subsequent prosecution.

The High Court rejected these arguments, finding that the prosecuted thefts were factually distinct from those handled by the Family Court and were not part of a single comprehensive offense. D appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis: "Case Adjudicated" Means Facts Specified in the Disposition

The Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's decision and dismissed D's appeal, providing a clear and narrow interpretation of "case adjudicated" under Juvenile Act Article 46.

Rejection of Single Offense Theory:

First, the Court addressed the criminal law argument. It agreed with the High Court's factual assessment that the thefts prosecuted criminally (Dec 5, Jan 8) were "entirely different facts" (mattaku bekui no jijitsu) from the four thefts listed in the Family Court's disposition document. Each incident was deemed a "separate and independent fact" (bekko dokuritsu no jijitsu). The Court found it "impossible to recognize" these separate acts as constituting a single comprehensive offense driven by a singular intent. Therefore, the premise for the first double jeopardy argument failed.

Strict Interpretation of "Case Adjudicated":

More importantly, the Court directly interpreted the scope of Juvenile Act Article 46:

"...the term 'case adjudicated' (shinpan o heta jiken) in Juvenile Act Article 46 refers only to the criminal facts described in the disposition decision document (ketteisho kisai no hanzai jijitsu nomi) as being the subject of the protective disposition, and should not be interpreted to encompass facts other than said criminal facts."

This ruling explicitly rejected the broader interpretations offered by the defense.

- It rejected the idea that Article 46 protection extends to related but unlisted offenses, even if arguably part of the same course of conduct (unless they legally constitute a single comprehensive offense with the listed facts, which was found not to be the case here).

- It implicitly rejected the "adjudication of personality" theory, confirming that the double jeopardy protection attaches to specific facts adjudicated, not the juvenile's overall character or history prior to the disposition.

Conclusion:

Since the thefts for which D was criminally convicted (Dec 5 & Jan 8) were factually separate from and not listed in the Family Court's disposition document, the legal effect of the protective disposition under Article 46 did not extend to these offenses. Consequently, the constitutional and statutory claims based on double jeopardy were deemed to lack the necessary premise, and the appeal was dismissed.

Rationale and Significance

This 1961 decision remains a foundational ruling on the scope of double jeopardy protection within Japan's juvenile justice system. Its significance lies in several areas:

- Fact-Specific Protection: It established that the protection afforded by Article 46 is tied to the specific delinquent acts formally identified by the Family Court as the basis for its protective disposition. This aligns with the view, which became dominant over time, that juvenile proceedings, while focused on welfare, must also properly adjudicate the underlying facts of delinquency, especially when those facts constitute crimes.

- Importance of the Disposition Document: The ruling underscores the critical role of the formal disposition document (ketteisho). As required by procedural rules (like Juvenile Hearing Rule 36), this document must specify the delinquent facts found proven. This documented finding serves to clearly define the boundaries of the Article 46 double jeopardy protection.

- Exclusion of Unadjudicated Facts (Yozai): The decision clarifies that other potential offenses (yozai) committed by the juvenile, even if known to the court and considered as part of the overall assessment of the juvenile's character or need for protection, are not covered by the Article 46 bar unless they are formally included in the disposition's factual basis. This mirrors the principle in adult criminal law where considering other offenses merely for sentencing does not trigger double jeopardy for those other offenses.

- Balancing Protection and Accountability: The ruling strikes a balance. It ensures that a juvenile is not punished twice for the specific acts addressed by a protective disposition. However, it prevents the juvenile system from inadvertently granting blanket immunity for all prior misconduct, allowing for accountability through later prosecution for distinct offenses not formally adjudicated by the Family Court.

While the decision provides legal clarity, commentators have noted a potential downside: prosecuting other offenses (yozai) criminally after a juvenile has already received a protective disposition aimed at rehabilitation can potentially undermine the effectiveness of those rehabilitative efforts. This suggests a need for careful prosecutorial discretion even when prosecution is legally permissible.

In summary, the 1961 Supreme Court decision established that the double jeopardy protection under Japan's Juvenile Act Article 46 following a protective disposition is strictly limited to the specific delinquent acts identified in the Family Court's formal disposition order. It does not provide broader immunity covering related but unadjudicated offenses or the juvenile's general past conduct.