Double Claim, Double Pay? Debtor's Liability After Paying a Subordinate Claimant in Japan

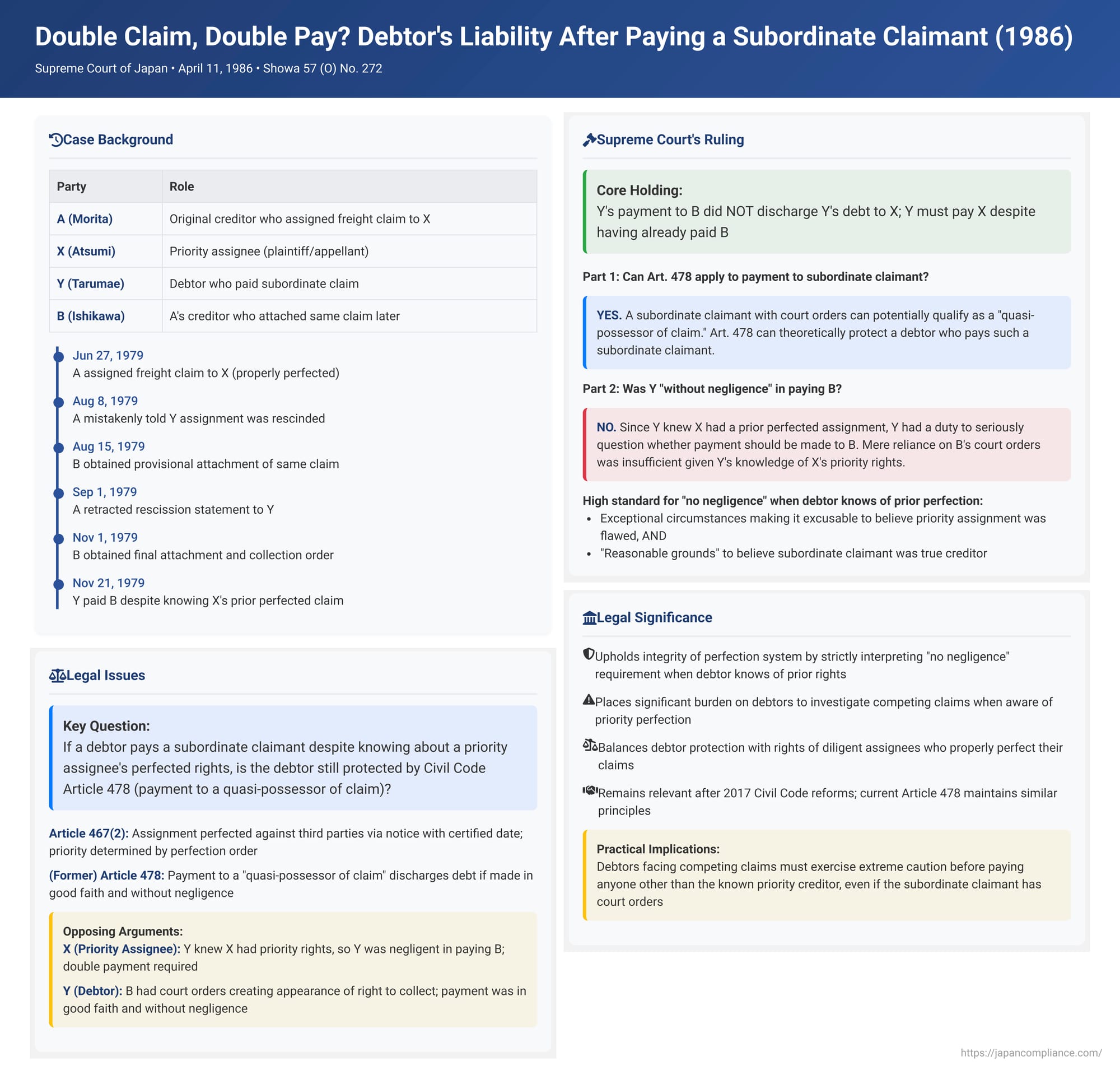

When a debt is assigned (sold) from one creditor to another, Japanese law has clear rules (primarily under Article 467 of the Civil Code) about how the new creditor (assignee) must "perfect" their claim to make it valid against the debtor and other third parties. Priority is generally given to the first to properly perfect. But what happens if a debtor, despite knowing about a properly perfected assignment to Assignee X, ends up paying a different party—say, Creditor B, who attached the same debt later or was a subordinate assignee? Can the debtor argue they've already paid and are off the hook with Assignee X? The Supreme Court of Japan tackled this complex scenario in a judgment on April 11, 1986 (Showa 57 (O) No. 272), focusing on the (now former) Civil Code Article 478 concerning payments made to a "quasi-possessor of a claim."

The Legal Framework: Priority of Assignment vs. Payment to an Apparent Creditor

Two key legal provisions were at play:

- Civil Code Article 467(2) (Perfection and Priority): This article (in its pre-2017 form, but the principle remains) established that for an assignment of a designated claim to be effective against third parties (like other assignees or attaching creditors), the notice to the debtor (or the debtor's consent) must be made using a document with a "certified date" (kakutei hizuke). Priority among competing claimants is determined by the order in which this perfection is completed (typically, when the certified notice reaches the debtor).

- (Former) Civil Code Article 478 (Payment to a Quasi-Possessor of a Claim): This article provided a defense for debtors. It stated that a payment made to a "quasi-possessor of a claim" (saiken no jun-senyūsha)—someone who isn't the true creditor but has the outward appearance of being entitled to receive payment—discharges the debtor if the debtor made the payment in good faith (believing the recipient was the true creditor) and without negligence. (The current Civil Code Article 478 uses slightly different wording but embodies a similar concept: "one who has the outward appearance of a person entitled to receive payment in light of common sense in transaction.")

The tension arises when the party with priority under Article 467(2) is not the party who receives payment from the debtor. Can the debtor still be discharged under Article 478?

Facts of the 1986 Case: A Tangled Web of Assignment, Rescission, and Attachment

The case involved a series of confusing events for the debtor:

- The Parties:

- X (Atsumi Unyu K.K.): The initial, and priority, assignee of a freight charge claim.

- A (Morita Doboku Unyu Y.K.): The original creditor who assigned the claim to X.

- Y (Tarumae Unyu Y.K.): The debtor who owed the freight charges.

- B (ISHIKAWA Shōzō): Another creditor of A, who later attached the same claim.

- The Assignment and Perfection: On June 27, 1979, A assigned its claim against Y (the Debtor) to X. A notified Y of this assignment using a document with a certified date, which Y received around June 28, 1979. This properly perfected X's claim, giving X priority. X even received a partial payment from Y in early July.

- Confusion Ensues:

- Around August 8, 1979, A (the assignor) mistakenly informed Y (the Debtor) that the assignment to X had been rescinded due to an alleged default by X.

- Around September 1, 1979, A realized its mistake and notified Y that the rescission was retracted. This back-and-forth understandably made Y suspicious of A's inconsistent actions.

- Meanwhile, B (another creditor of A) obtained a provisional court order to attach a significant portion of the claim (the "Disputed Portion") on August 15, 1979, followed by a final attachment and collection order on November 1, 1979. Both these court orders were served on Y.

- Debtor Pays the Subordinate Claimant: Y (the Debtor) had initially heard about the (later retracted) rescission of X's assignment and believed the claim had reverted to A. After receiving B's provisional attachment order, then A's retraction of the rescission, and then B's final attachment and collection order, Y was in a difficult position. Pressured by repeated demands from B's lawyer and, crucially, believing that court-issued attachment and collection orders must be valid, Y paid the Disputed Portion (over 2.15 million yen) to B on November 21, 1979. This payment was made despite X having also made demands for the remaining balance of its prior-perfected assigned claim.

- The Lawsuit: X sued Y for the amount Y had paid to B. The lower courts sided with Y, ruling that Y's payment to B was a valid discharge under (former) Article 478 because B, armed with court orders, was a "quasi-possessor of the claim," and Y had paid in good faith and without negligence. X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Two-Part Ruling

The Supreme Court reversed the lower courts' decision regarding the payment to B, finding that it did not discharge Y's debt to X for that amount.

Part 1: Can a Subordinate Claimant (like an Attaching Creditor) Be a "Quasi-Possessor"? YES, Potentially.

The Court first addressed whether Article 478 could even apply when payment is made to someone who is demonstrably a subordinate claimant under the priority rules of Article 467(2).

- It held that Article 478 can theoretically apply in such situations. The rules for determining priority of claims (Article 467(2)) and the rules for determining if a payment to an apparent creditor is valid (Article 478) address different legal questions.

- If a debtor pays a subordinate assignee or an attaching creditor (like B), genuinely and non-negligently believing them to be the true and rightful creditor based on their outward appearance of entitlement, then Article 478 could protect the debtor and validate the payment. The Court noted that even if this means the priority assignee (X) cannot recover from the debtor (Y), X is not left without remedy, as X could still pursue the subordinate party (B) who received the payment under principles of unjust enrichment.

- In this case, B, by virtue of having obtained court-issued attachment and collection orders, possessed the outward appearance of someone entitled to collect the debt and could therefore be considered a "quasi-possessor of the claim." This opened the door for Article 478 to potentially apply.

Part 2: Was the Debtor (Y) "Without Negligence" in Paying B? NO.

This was the crucial part of the ruling. While Article 478 could apply, the conditions for it – specifically, the debtor acting "without negligence" – were not met.

- High Standard for "No Negligence" in This Context: The Supreme Court set a high bar. Since Article 467(2) clearly establishes that the priority assignee (X) is the rightful creditor to whom the debtor should pay, for a debtor's payment to a subordinate claimant (B) to be considered "without negligence" under Article 478, there must be:

- Exceptional circumstances making it excusable for the debtor to have mistakenly believed that the priority assignee's (X's) assignment or its perfection was somehow flawed or ineffective, AND

- "Reasonable grounds" for the debtor to believe that the subordinate claimant (B) was, in fact, the true and rightful creditor.

- Application to the Facts:

- Y (the Debtor) knew that X's Assignment Notice had been properly perfected and had reached Y before B's provisional attachment order was served. This prior perfected right of X was a critical piece of information.

- This knowledge alone, the Court reasoned, should have caused Y to seriously question whether payment should be made to B.

- The mere fact that B's attachment and collection orders were issued by a court was not sufficient to provide Y with "reasonable grounds" to believe B was the true creditor, especially given Y's awareness of X's pre-existing and superior perfected rights. A's earlier confusing (but retracted) rescission notice did not absolve Y of this duty of care towards X.

- Therefore, Y's action of "summarily concluding" that the court orders in favor of B were without error and consequently paying B (who, vis-à-vis X, lacked the ultimate right to collect) could not be deemed to have been without negligence.

As a result, Y's payment to B did not discharge Y's obligation to X for that amount. The Supreme Court effectively determined that X's bankruptcy claim against Y's estate should include the sum Y had improperly paid to B.

Significance: Balancing Debtor Protection and Assignee Rights

This 1986 judgment offers important insights into the delicate balance between protecting a debtor who pays in good faith and upholding the rights of a creditor who has diligently perfected their assignment.

- Upholding the Integrity of the Perfection System: While acknowledging the theoretical applicability of Article 478 (payment to a quasi-possessor), the Supreme Court's stringent interpretation of the "no negligence" requirement effectively safeguards the priority system established by Article 467(2). A prior perfected right cannot be easily defeated by a debtor's payment to a later, subordinate claimant.

- Significant Burden on the Debtor: The decision underscores that debtors face a considerable responsibility when confronted with competing claims to a debt. They cannot simply pay the party that appears most insistent or is armed with official-looking documents (like court orders) if they are aware of another party possessing a prior, properly perfected claim. To be excused for paying the "wrong" person, the debtor must demonstrate compelling and reasonable grounds for believing the priority claim was invalid. Ignorance or a simplistic reliance on later developments is unlikely to suffice if prior rights were known.

- Refining the "Quasi-Possessor" Doctrine: The ruling clarifies the application of the "payment to a quasi-possessor" doctrine in the specific context of competing perfected claims on an assigned debt. It signals that the "outward appearance" of the subordinate claimant must be exceptionally strong, and the reasons for disbelieving the priority claimant's rights particularly compelling, for the debtor's payment to the subordinate to be validated.

Relevance Today (Post-2017 Civil Code Reform)

Although (former) Article 478 was rephrased during the 2017 Civil Code reforms (the current Article 478 now refers to "one who has the outward appearance of a person entitled to receive payment in light of common sense in transaction"), the fundamental principles of protecting a debtor who pays in good faith and without negligence to an apparent obligee remain. This 1986 Supreme Court judgment, with its careful balancing act and its strict approach to what constitutes "no negligence" in the face of a known prior perfected right, continues to offer valuable guidance in interpreting these principles.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1986 decision in this freight charge claim case serves as a crucial reminder of the diligence required from debtors when faced with multiple claimants to a single debt. While the law offers protection for payments made in good faith to those who appear to be rightful creditors, this protection is not absolute. If a debtor is aware that one assignee has properly perfected their claim with priority, the debtor must exercise extreme caution before paying any other, subordinate claimant. Simply relying on subsequent court orders obtained by that subordinate claimant, without a very strong and justifiable reason to believe the priority assignment is defective, will likely be considered negligent, potentially exposing the debtor to the risk of having to pay the debt twice.