Domicile in Tax Law: Japan's Supreme Court on the "Principal Base of Life" and Tax Avoidance Motives

Judgment Date: February 18, 2011

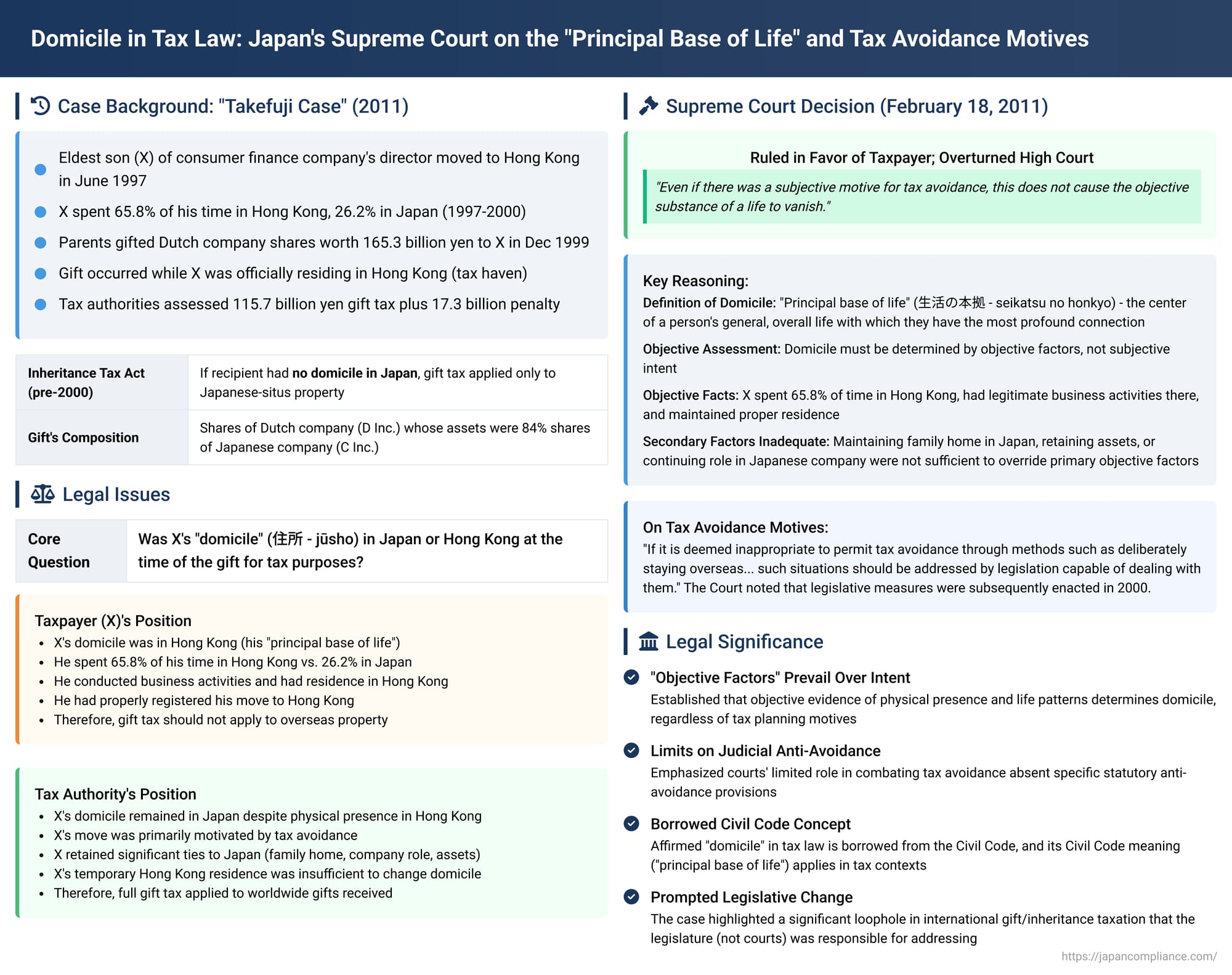

In a high-profile case with significant implications for Japanese tax law, often referred to colloquially as the "Takefuji Case," the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a pivotal judgment on the interpretation of "domicile" (住所 - jūsho) for gift tax purposes. The ruling emphasized an objective assessment of an individual's "principal base of life" and controversially concluded that a taxpayer's subjective motive to avoid taxes does not, in itself, negate the objective establishment of a domicile outside Japan, even if such a move facilitates substantial tax savings. The decision underscored the judiciary's deference to the literal interpretation of tax laws and placed the onus on the legislature to address perceived loopholes.

The Multi-Billion Yen Gift and a Contentious Domicile

The appellant, X, was the eldest son of A, the representative director of a major Japanese consumer finance company (C Inc.), and A's wife, B. The case revolved around a substantial gift X received from his parents in December 1999. This gift consisted of shares in D Inc., a Dutch private limited liability company, which in turn held a significant number of shares (over 84% of D Inc.'s assets) in C Inc. The value of this gift was assessed by the tax authorities at approximately 165.3 billion yen, leading to a gift tax determination of roughly 115.7 billion yen, plus a non-filing penalty of about 17.3 billion yen.

The core of the dispute was X's "domicile" at the time of the gift. Under Japanese Inheritance Tax Act provisions applicable at the time (specifically, Article 1-2, prior to its amendment on March 31, 2000):

- If a donee (recipient of a gift) had a domicile in Japan, they were considered an "unlimited taxpayer" and subject to Japanese gift tax on all gifted property, regardless of whether the property was located in Japan or overseas.

- If a donee did not have a domicile in Japan, they were a "limited taxpayer." Gift tax was only levied if the gifted property was located within Japan. Gifts of foreign-situs property to non-domiciled donees were not subject to Japanese gift tax.

It was a generally known tax planning strategy at the time for individuals to move their domicile to a jurisdiction like Hong Kong (which did not levy gift tax) and receive gifts of foreign property, thereby legally avoiding Japanese gift tax.

X's Move to Hong Kong

X had joined his father's company, C Inc., in 1995 and became a director in June 1996. In May 1997, C Inc., upon A's proposal, decided to establish a subsidiary in Hong Kong to pursue overseas business opportunities (this later shifted to acquiring local Hong Kong firms). X departed for Hong Kong on June 29, 1997, and was appointed as C Inc.'s resident officer in Hong Kong for information gathering and investigation. He subsequently became a director of two acquired Hong Kong local entities.

X remained based in Hong Kong from June 29, 1997, until December 17, 2000 (a period of approximately 3.5 years, referred to as "the subject period"), when he reportedly abandoned his duties and disappeared. The gift in question occurred on December 27, 1999, about 2.5 years into X's Hong Kong assignment.

During "the subject period":

- Stay Durations: X spent approximately 65.8% of his time in Hong Kong and about 26.2% in Japan.

- Work Activities: He engaged in business activities for C Inc. and the Hong Kong entities for a total of 168 days in Hong Kong, including meetings with local contacts. In Japan, he attended most of C Inc.'s monthly board meetings and other significant business meetings, such as executive committees and national branch manager conferences. He was promoted within C Inc. to Managing Director in June 1998 and then to Senior Managing Director in June 2000.

- Living Arrangements: X, who was single, resided alone in a serviced apartment in Hong Kong ("the HK residence"). This apartment was leased for two-year terms, renewed once during his stay. When in Japan, he stayed with his parents and younger brother at the family's residence in Sugamo, Tokyo ("the Sugamo residence"), which had been his home before his departure.

- Assets: The vast majority of X's personal assets (over 99.9%, including substantial holdings in C Inc. stock and large bank deposits and borrowings) remained in Japan. His assets in Hong Kong consisted primarily of savings from his remuneration, amounting to around 50 million yen.

- Formalities: Upon moving to Hong Kong, X filed a "moving-out notification" with his Japanese municipality, indicating Hong Kong as his new residence. He also submitted documents to the Japanese Consulate-General in Hong Kong and the Hong Kong Immigration Department, listing the HK residence as his address. However, he did not notify all of his banks in Japan of his change of address. For C Inc. internal documents like appointment acceptance letters, he sometimes used the Sugamo residence address, while public filings like securities reports listed his Hong Kong address.

The tax authorities (the Sugamo Tax Office Chief) determined that X's domicile remained in Japan at the time of the gift, leading to the substantial gift tax assessment. X challenged this, arguing his domicile was in Hong Kong.

Lower Court Rulings

The Tokyo District Court (trial court) found in favor of X, concluding that his domicile was not in Japan at the time of the gift. However, the Tokyo High Court (appellate court) reversed this decision, holding that X's domicile was indeed in Japan. The High Court emphasized X's awareness of the tax avoidance purpose of his Hong Kong move and his actions in managing his stay durations to support this objective. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Definition and Application of "Domicile"

The Supreme Court overturned the Tokyo High Court's ruling and reinstated the trial court's decision in favor of X, effectively cancelling the gift tax assessment. The Court's judgment meticulously defined "domicile" and applied it to the complex facts, giving significant weight to objective factors over subjective intent.

The Legal Meaning of "Domicile"

The Supreme Court began by defining "domicile" (住所 - jūsho) as used in Article 1-2 of the Inheritance Tax Act:

"Where the gifted property is located outside Japan, the donee having a domicile within Japan at the time of receiving said gift is a requirement for gift tax liability (Article 1-2, Item 1 of the Act). The term 'domicile' herein, in the absence of any special reason warranting a contrary interpretation, refers to the principal base of life (seikatsu no honkyo - 生活の本拠), that is, the center of a person's general, overall life with which they have the most profound connection. Whether a certain place constitutes a person's domicile is to be determined objectively by whether it possesses the substance of being the principal base of life."

The Court cited several of its own precedents, including a 1954 Grand Bench decision concerning domicile for electoral law purposes, to support this objective definition.

Application to X's Circumstances

Applying this objective test, the Supreme Court found:

- Objective Establishment of Life in Hong Kong: X had been assigned to Hong Kong as a resident officer for C Inc. and a director of its local entities. The gift occurred approximately 2.5 years after this assignment began. He had formally registered his move to Hong Kong. During the roughly 3.5-year "subject period," he spent approximately two-thirds of his time residing in the leased HK residence and conducted business activities there. The Court found that these activities and his stay in Hong Kong were not a mere sham devoid of substance, created solely for tax avoidance.

- Comparison with Activities in Japan: In contrast, X spent about one-quarter of his time in Japan, staying at the Sugamo residence and attending to C Inc. business.

- Conclusion on "Principal Base of Life": Based on these objective facts, the Supreme Court concluded that, at the time of the gift, the HK residence possessed the substance of being X's principal base of life, while the Sugamo residence in Japan did not.

The Irrelevance of Tax Avoidance Motive to Objective Facts

A crucial part of the Supreme Court's reasoning was its response to the High Court's emphasis on X's tax avoidance motive:

The High Court had argued that because X recognized the tax avoidance purpose of his Hong Kong move and consciously managed his stay durations to maintain a majority presence outside Japan, his time spent in Hong Kong should not be the primary factor in determining domicile. The Supreme Court rejected this:

"As stated before, whether a certain place constitutes a domicile is to be determined by whether it objectively possesses the substance of being the principal base of life. Even if there was a subjective motive for tax avoidance, this does not cause the objective substance of a life to vanish. Therefore, the fact that X adjusted his stay durations with such a motive cannot be a reason to deny that the HK residence was the principal base of life for X, who actually spent approximately two-thirds of the subject period in Hong Kong (about 2.5 times his stay in Japan) under the circumstances described."

The Court further stated: "This conclusion is an unavoidable consequence of the Act using the Civil Code concept of 'domicile' to define tax liability. If, on the other hand, it is deemed inappropriate to permit tax avoidance through methods such as deliberately staying overseas for an extended period to create the conditions for such avoidance—a situation perhaps not originally envisaged by tax practice—then, as there are limits to what can be achieved by interpretation of the Act, such situations should be addressed by legislation capable of dealing with them." The Court pointed out that legislative measures to this effect were indeed subsequently enacted in 2000.

Dismissal of Other Factors Emphasized by the High Court

The Supreme Court also addressed other factors the High Court had relied upon to find X's domicile in Japan, deeming them insufficient to overturn the objective evidence of his Hong Kong base:

- Staying at the family home (Sugamo residence) when in Japan: This was a natural choice for accommodation during return trips.

- X's important position within C Inc. (Japan): While significant, it did not outweigh the substantial difference in stay durations (Hong Kong vs. Japan) to make Japan the principal base of life.

- Not moving substantial household effects to Hong Kong: Not unreasonable considering the cost and hassle, and the fact that he was in a serviced apartment.

- Staying in a serviced apartment in Hong Kong: This was a natural and reasonable choice for a single individual on an overseas assignment with X's status, remuneration, and wealth; it did not imply that the stay was not intended to be long-term.

- Keeping most assets in Japan: Not inconsistent with the behavior of many expatriates.

- Not updating address with all financial institutions: Given that X had formally registered his move to Hong Kong for official purposes (like resident registration), failing to update some non-essential bank records out of convenience was not seen as definitively negating his intention to reside in Hong Kong.

The Supreme Court found that none of these factors were sufficient to deny the objective reality that the HK residence was X's principal base of life.

Judgment: Gift Tax Assessment Cancelled

The Supreme Court concluded that X did not have a domicile in Japan (as defined in Article 1-2, Item 1 of the Inheritance Tax Act) at the time of receiving the gift. Therefore, he was not liable for Japanese gift tax on the foreign-situs shares, and the tax authorities' assessments were illegal. The High Court's judgment was reversed, and the first instance judgment (in favor of X) was upheld.

Supplementary Opinion of Justice Sudo

Justice Masahiko Sudo, while concurring with the majority opinion, issued a supplementary opinion expressing some nuanced reflections:

- Unease with the Outcome: Justice Sudo acknowledged the significant public discomfort ("not an insignificant sense of unease from the perspective of general legal sentiment") that could arise from a situation where an enormous amount of wealth (165.3 billion yen), substantially derived from C Inc.'s domestic business activities, was transferred from parents to son tax-free through a carefully constructed "tax avoidance scheme." He noted X's optimal ability to pay tax and the implications for wealth redistribution in Japan.

- Objective Domicile vs. Reality: He pondered whether, with modern advancements in communication and transportation, an individual might objectively have "bases of life" in multiple countries simultaneously. Looking at X's continued significant activities and ties in Japan, one might argue that Japan also remained a base of life.

- Singularity of Domicile in Law: However, Justice Sudo pointed out that established Japanese case law treats "domicile" (for a single legal purpose) as singular. The concept of multiple concurrent domiciles is not generally accepted in Japanese legal interpretation. Therefore, a choice had to be made between Hong Kong and Tokyo. Given X's significantly longer physical presence in Hong Kong and his business activities there, Hong Kong had to be considered the stronger candidate for the principal base of life, even if the stay was orchestrated as part of the tax avoidance plan and was not intended to be permanent beyond the scheme's completion. The Hong Kong presence was not a mere "sham."

- Limits of Judicial Interpretation under "Taxation by Law": Despite the potentially unpalatable outcome, Justice Sudo emphasized the supremacy of the constitutional principle of "taxation by law" (Constitution, Articles 30 and 84). This principle demands that tax liability be based on clear legal provisions, interpreted strictly. Courts cannot engage in expansive interpretations, apply general anti-abuse doctrines where no specific statutory basis exists, or make special factual findings merely to negate a tax avoidance scheme. If the law, strictly interpreted, allows for such an outcome, the solution lies in legislative reform, not judicial activism. He noted that the law was indeed changed subsequently.

Significance of the "Takefuji Case"

This ruling is a landmark in Japanese tax law for several critical reasons:

- "Borrowed Concept" of Domicile: It affirmed that "domicile" in the Inheritance Tax Act is a "borrowed concept" from the Civil Code, meaning it should be interpreted in line with the Civil Code's definition of "principal base of life," which focuses on objective factors.

- Objective Test for Domicile Prevails: The case strongly reinforces that the determination of domicile for tax purposes rests on an objective assessment of where an individual's life is centered. Subjective motives, including a clear intention to avoid taxes, do not invalidate an objectively established foreign domicile, provided the foreign presence is genuine and not a mere facade.

- Limits of Judicial Anti-Avoidance: The judgment starkly illustrates the limitations placed on Japanese courts in combating tax avoidance schemes in the absence of specific statutory anti-avoidance rules. The principle of "taxation by law" requires a clear legal basis for taxation, and courts are generally reluctant to create one through interpretation where the legislature has not acted.

- Call for Legislative Action: The Supreme Court explicitly stated that if tax avoidance methods like the one employed by X are deemed undesirable, the appropriate remedy is legislative change, not judicial reinterpretation of existing law to achieve a particular fiscal outcome. This case served as a high-profile example that likely spurred or validated subsequent legislative efforts to close such loopholes in international gift and inheritance taxation.

The "Takefuji Case" remains a pivotal, though sometimes controversial, example of the Japanese judiciary navigating the complex intersection of statutory interpretation, constitutional principles, and the challenges posed by sophisticated tax planning. It highlights a legal tradition that prioritizes textual fidelity and the rule of law, even when the results may seem counterintuitive from a purely fiscal or social equity standpoint.