Dollar Debts, Yen Judgments: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Foreign Currency Claims

Date of Judgment: July 15, 1975

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

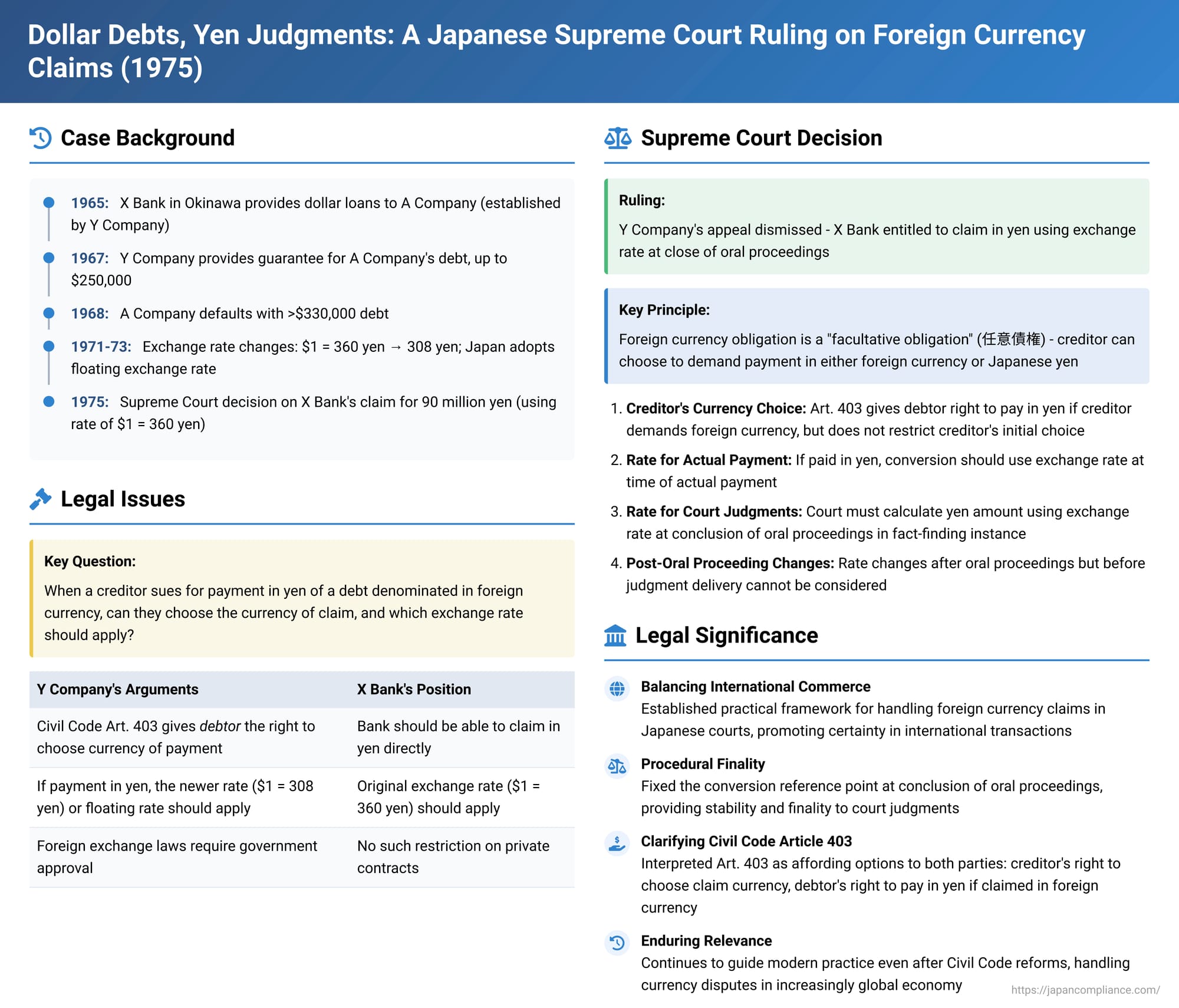

In an increasingly globalized economy, contracts and debts denominated in foreign currencies are commonplace. However, when disputes arise and litigation ensues in a domestic court, questions emerge: Can a creditor demand payment in the local currency? If so, at what exchange rate should the conversion be made, especially when currency values fluctuate? A key Japanese Supreme Court decision from July 15, 1975, provided crucial answers to these questions, establishing principles that continue to guide the handling of foreign currency-denominated obligations in Japanese courts.

The Factual Background: A Dollar Guarantee in a Changing World

The case arose from a series of business dealings against a backdrop of shifting economic landscapes, including the U.S. administration of Okinawa and later global currency realignments:

- X Bank (the plaintiff), located in Naha City, Okinawa, had provided loans to A Company, an entity established in Okinawa by Y Company (the defendant). Y Company was based in Nagoya, Japan, and had been involved in construction for U.S. military bases in Okinawa since the late 1950s.

- The initial loan agreement in 1965 between X Bank and A Company was denominated in U.S. dollars, with a credit limit of $110,000.

- In 1967, when this credit limit was increased to $350,000, Y Company provided a guarantee to X Bank for A Company's obligations. This guarantee had a limit of $250,000 and was effective from August 1967 to August 1970. A Company typically serviced its debt by assigning its U.S. dollar receivables from the U.S. military to X Bank.

- A Company eventually defaulted on its repayments, with overdue debts exceeding $330,000 by March 1968.

- X Bank subsequently sued Y Company (as the guarantor) in a Japanese court. The bank claimed the yen equivalent of the $250,000 guarantee limit, calculated at the then long-standing exchange rate of $1 = 360 yen, for a total of 90 million yen.

- Both the Nagoya District Court (first instance) and the Nagoya High Court (second instance) ruled in favor of X Bank. Y Company appealed to the Supreme Court.

It is important to note the context: at the time the guarantee was made, Okinawa was under U.S. administration, and the $1 = 360 yen exchange rate was part of a fixed-rate global system. By the time the case reached the higher courts, significant changes had occurred, including the move towards floating exchange rates.

The Guarantor's Arguments Before the Supreme Court

Y Company raised several points on appeal, but two were central to the currency issue:

- Debtor's Right to Choose Currency of Payment: Y Company argued that because the guaranteed debt was specified in a foreign currency (U.S. dollars), Article 403 of the Japanese Civil Code applied. They contended this article gave the debtor (Y Company) the exclusive right to choose whether to pay in U.S. dollars or Japanese yen. Therefore, X Bank's direct claim for a specific yen amount was improper.

- Incorrect Conversion Rate: Y Company further argued that if payment in yen was to be made, the conversion rate was incorrect. They pointed out that by a Ministry of Finance decision on December 18, 1971 (after the High Court's oral proceedings had concluded on November 25, 1971, but before its judgment was delivered on October 24, 1972), the official standard exchange rate had changed to $1 = 308 yen. This would have reduced the yen equivalent of $250,000 to 77 million yen. Additionally, Y Company noted that Japan had adopted a floating exchange rate system from February 14, 1973, arguing that any payment should be based on the prevailing floating rate, not the old fixed rate used by the lower courts.

(Y Company also argued that the guarantee contract was void under Japan's foreign exchange laws, or at least payment should be conditional on Ministry of Finance approval. The Supreme Court dismissed this, stating that these laws were regulatory and did not invalidate private contracts, nor did they make judgments conditional upon such approvals.)

The Supreme Court's Key Rulings on Foreign Currency Obligations

The Supreme Court dismissed Y Company's appeal, laying down clear principles regarding foreign currency-denominated claims:

1. Creditor's Right to Claim in Local or Foreign Currency:

The Court declared that a monetary obligation where the amount is specified in a foreign currency is a "so-called 'facultative obligation'" (いわゆる任意債権 - iwayuru nin'i saiken). This means that the creditor has the right to demand payment from the debtor in either the specified foreign currency or in Japanese currency.

The Court clarified that Article 403 of the Civil Code—which states, "If the amount of a claim is specified in a foreign currency, the debtor may make payment in Japanese currency at the exchange rate current at the place of performance"—merely grants the debtor a right to pay in Japanese currency if the creditor has demanded payment in the foreign currency. It does not restrict the creditor's initial choice of which currency to claim in.

2. Conversion Rate for Actual Payment:

The Court affirmed the general principle that when a monetary obligation designated in a foreign currency is actually paid in Japanese currency, the conversion should be made using the foreign exchange rate prevailing at the time of actual payment. This ensures the creditor receives the economic equivalent of the foreign currency amount.

3. Conversion Rate for Court Judgments:

However, the Court established a distinct rule for when a Japanese court renders a judgment for payment in Japanese yen concerning a foreign currency-denominated debt. In such cases, the court must calculate the yen amount using the foreign exchange rate prevailing at the time of the conclusion of oral proceedings in the fact-finding instance (事実審の口頭弁論終結時 - jijitsushin no kōtō benron shūketsu-ji).

Crucially, the Supreme Court stated that any changes in the exchange rate occurring after the conclusion of oral proceedings but before the judgment is formally delivered cannot be taken into account by the court in that judgment.

Applying this to Y Company's arguments, X Bank was entitled to sue for yen, and the High Court correctly used the exchange rate at the close of its oral proceedings. Subsequent rate changes were irrelevant to the judgment amount.

Rationale and Implications

The commentary by Mr. Itatani accompanying this case sheds further light on the decision's underpinnings and impact:

- Why the Creditor Can Choose Currency of Claim:

- Practicality: Japanese courts primarily operate in yen, so allowing creditors to claim in yen simplifies litigation and enforcement processes.

- Nature of Foreign Currency Debts: Often, the foreign currency designation serves to express the value of the obligation (making it a "value debt" - 金額債権, kingaku saiken) rather than a strict demand for the physical delivery of specific foreign banknotes.

- Civil Code Art. 403: Viewed as granting a supplemental right to the debtor, not limiting the creditor.

- The "Facultative Obligation" (任意債権 - nin'i saiken) Concept:

- A facultative obligation typically involves one primary object of performance, but one party (either creditor or debtor) has the right to substitute it with another. The Supreme Court's use of "so-called facultative obligation" for foreign currency debts might not be a strict application of this traditional civil law concept, as monetary debts (unlike, for example, the delivery of a specific unique item) are generally not subject to impossibility of performance, which is a scenario where facultative rights often become relevant.

- Why the Judgment Conversion Rate is Fixed at Close of Oral Proceedings:

- Finality of Judgments: Japanese procedural law generally requires judgments to be for a fixed sum. Fixing the conversion rate at the close of the fact-finding stage provides this certainty.

- Consistency: It aligns with how courts generally handle other types of value fluctuations that might occur after oral arguments have concluded but before judgment is rendered. It prevents potentially endless disputes over rate changes during the judgment deliberation period.

- Relationship with "Time of Actual Payment" Principle:

- While the judgment amount is fixed based on the rate at the close of oral proceedings, the underlying principle of Article 403—that actual payment in yen should reflect the value at payment time—remains. If a creditor sues for payment in the foreign currency, and the debtor then opts to pay in yen, the conversion happens at the payment-time rate. Similarly, if a yen judgment (based on the earlier rate) is later enforced, the actual value received by the creditor might differ if exchange rates have moved significantly, but the legal obligation is fixed by the judgment. The judgment in yen essentially crystallizes the value at the latest feasible point in the court proceedings.

Broader Context and Modern Relevance

This 1975 Supreme Court decision remains a cornerstone of Japanese law regarding foreign currency obligations. Its principles were considered during the major revisions to the Japanese Civil Code in 2017 (effective 2020) but were ultimately left as established case law rather than being explicitly codified.

The ruling continues to be highly relevant in today's world of international trade and finance, where cross-currency transactions are routine. It informs how businesses manage currency risk and how financial disputes are resolved.

Looking ahead, the very definition of "foreign currency" as envisaged by Article 403 (typically, a currency issued by a foreign state with legal tender status, governed by its own lex monetae or law of the currency) may face new questions with the rise of digital currencies. Whether state-planned electronic payment instruments not directly backed by central bank liability, or decentralized cryptocurrencies (even those adopted as legal tender by some nations, like Bitcoin in El Salvador), fall under the ambit of Article 403 will require careful consideration in light of evolving international norms and practices.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1975 ruling provided much-needed clarity on the handling of foreign currency-denominated debts within the Japanese legal system. It affirmed the creditor's flexibility in choosing the currency of their claim in court, while establishing a practical and definitive rule for determining the conversion exchange rate when a judgment is rendered in Japanese yen. This decision balances the need for procedural certainty in litigation with the underlying principle of ensuring fair value in cross-currency obligations, and its tenets continue to shape the resolution of international financial disputes in Japan.