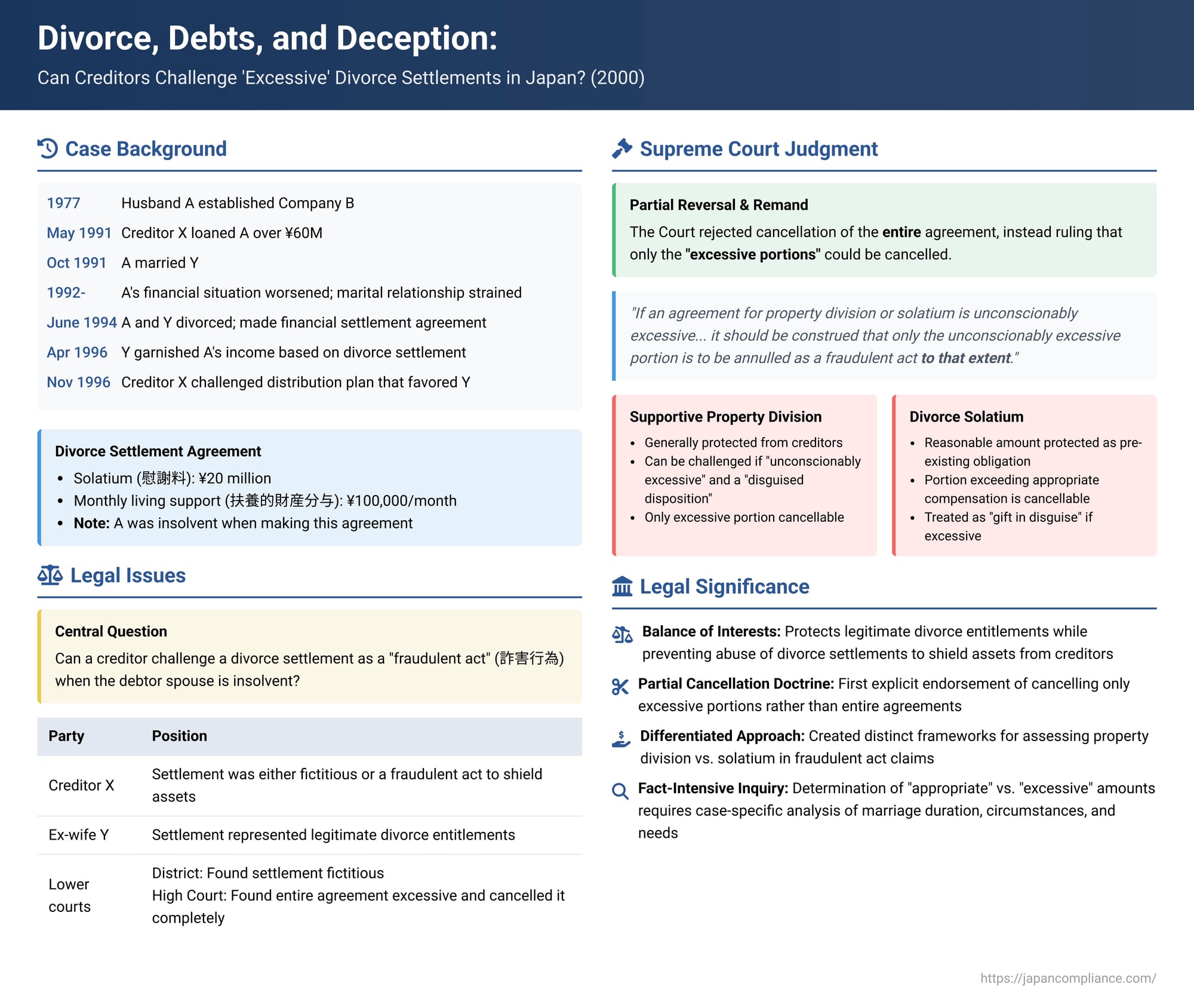

Divorce, Debts, and Deception: Can Creditors Challenge 'Excessive' Divorce Settlements in Japan? A 2000 Supreme Court Ruling

Date of Judgment: March 9, 2000

Divorce often involves complex financial settlements between spouses, including property division (財産分与 - zaisan bunyo) and payments for emotional distress, known as solatium (慰謝料 - isharyō). But what happens when one of the divorcing spouses is heavily indebted and facing insolvency? If that indebted spouse agrees to a particularly generous financial settlement with their ex-partner, can their existing creditors challenge this agreement as a "fraudulent act" (詐害行為 - saigai kōi) designed to unfairly shield assets from rightful claims? The Supreme Court of Japan tackled this critical issue in a decision on March 9, 2000 (Heisei 10 (O) No. 560), providing important clarifications on when and to what extent such divorce-related financial agreements can be annulled by creditors.

The Facts: A Bankrupt Husband, A Divorce Settlement, and Competing Creditors

The case involved a husband, A, who, along with his brother, had established Company B in 1977. By 1991, A was facing financial difficulties. On May 15, 1991, X, a creditor, lent A a significant sum, over 60 million yen. A's financial situation continued to worsen from around 1992. X eventually obtained a final court judgment confirming this loan claim against A. In August 1995, X took steps to enforce this judgment by garnishing 5 million yen of A's salary and executive compensation receivables from Company B (referred to as "the compensation receivables").

Meanwhile, A had married Y in October 1991. However, as A's financial troubles mounted around 1992, their marital relationship became strained, leading to their divorce by mutual agreement on June 1, 1994.

Shortly after the divorce, on June 20, 1994, A and Y entered into a formal agreement concerning financial settlements related to their divorce. This agreement (referred to as "the Agreement") was made into a notarized deed. Crucially, it was established that at the time of this Agreement, both A and Y were aware that A's debts far exceeded his assets (meaning he was insolvent) and that making such an agreement would likely prejudice his other creditors, including X. The Agreement stipulated that A would pay Y:

- Solatium (慰謝料 - isharyō) of 20 million yen.

- Monthly living support (生活補助費 - seikatsu hojohi, a form of supportive property division) of 100,000 yen.

A, however, failed to make any payments under this Agreement. Consequently, in April 1996, Y, based on the notarized Agreement, also took action to garnish A's compensation receivables from Company B, claiming a total of 22.2 million yen (comprising the 20 million yen solatium and 2.2 million yen in accumulated living support payments).

With both X and Y having garnished A's limited income stream, Company B deposited the available sum of just over 2.61 million yen with the Legal Affairs Bureau in June 1996 for distribution. In the proposed distribution plan prepared in November 1996, Y was allocated the lion's share (over 2.11 million yen) based on her divorce settlement claim, while X, despite his prior judgment, was allocated only about 490,000 yen.

X objected to this distribution. He filed a lawsuit arguing that the Agreement between A and Y was either a "fictitious transaction" (通謀虚偽表示 - tsūbō kyogi hyōji, a sham agreement with no real intent to be bound) and therefore void, or, alternatively, that it constituted a "fraudulent act" detrimental to creditors and should be cancelled by the court. X sought to have the entire deposited amount distributed to him.

The first instance court found the Agreement to be a fictitious transaction and thus void. The appellate court (High Court) disagreed that it was fictitious but found the agreed amounts of support and solatium to be "abnormally excessive" (ijō ni kōgaku). It ruled that the entire Agreement constituted a fraudulent act and ordered its complete cancellation. This resulted in Y's share of the distributed funds being reduced to zero, and X's claim to the funds was granted. Y then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court, arguing, among other things, that property division and solatium are distinct, and that a prior Supreme Court precedent from Showa 58 (1983)—which had dealt with property division as a comprehensive concept potentially including solatium—was distinguishable because her agreement with A had explicitly separated these elements.

The Supreme Court's Decision: A Nuanced Approach to Cancellation of Divorce Settlements

The Supreme Court partially agreed with Y, ultimately reversing the High Court's decision to cancel the entire Agreement and remanding the case for further calculation. The Court laid down distinct rules for assessing the cancellability of the supportive property division component and the solatium component of the divorce settlement.

1. Characterizing the Divorce Settlement Agreement:

The Supreme Court first analyzed the nature of "the Agreement," identifying its two main components:

- An agreement for A to pay Y monthly sums of 100,000 yen as "supportive property division" (扶養的財産分与 - fuyō-teki zaisan bunyo). This type of property division is aimed at providing for the post-divorce livelihood of a spouse.

- An agreement acknowledging A's obligation to pay Y 20 million yen as "solatium accompanying divorce" (離婚に伴う慰謝料 - rikon ni tomonau isharyō), meant as compensation for emotional distress caused by the divorce.

2. Rules for Challenging Supportive Property Division as a Fraudulent Act:

The Court referenced its 1983 precedent (Supreme Court, Showa 58.12.19) concerning property division. That precedent established that a property division agreement upon divorce is generally not considered a fraudulent act cancellable by creditors, unless it is "unconscionably excessive contrary to the purport of Article 768, paragraph 3 of the Civil Code [which mandates consideration of all circumstances in determining property division], and there are special circumstances sufficient to find it a disposition of property made under the guise of property division" (i.e., a disguised attempt to hide assets rather than a genuine settlement). The 2000 Court affirmed that this principle applies even when the property division is structured as periodic monetary payments, as in this case.

However, the 2000 Court then introduced a crucial development regarding the extent of cancellation: "And, where an agreement for monetary payment as property division accompanying divorce is made, if said special circumstances exist [i.e., it is unconscionably excessive and a disguised disposition], it should be construed that the unconscionably excessive portion is to be annulled as a fraudulent act to that extent." This explicit endorsement of partial cancellation for property division was a significant clarification, as the 1983 precedent had been less clear on whether an offending agreement would be struck down in its entirety or only the excessive part. The legal commentary suggests this also subtly shifted the analytical focus from whether the entire agreement was a "disguise" to whether parts of it are "unconscionably excessive."

3. Rules for Challenging Divorce Solatium as a Fraudulent Act:

The Supreme Court applied a different framework for the solatium portion of the Agreement:

- An agreement to pay a reasonable amount of divorce solatium is, in principle, an acknowledgment by one spouse of an existing obligation to compensate the other for damages (emotional distress) arising from their blameworthy conduct that led to the divorce. It is a confirmation and quantification of a pre-existing debt, not the creation of a new one. As such, an agreement to pay an appropriate amount of solatium is generally not considered a fraudulent act cancellable by creditors. The Court did not attach the "special circumstances/disguise" reservation here, as it did for property division.

- Excessive Solatium, However, is Vulnerable: The Court clarified: "If an agreement is made to pay an amount of solatium that exceeds the amount of damages for which the said spouse should be liable, then the portion of the agreement exceeding said amount of damages should be considered a gift of money under the guise of solatium payment or a new debt-creating act lacking consideration, and thus can be subject to the right of cancellation for fraudulent act." Only the truly excessive portion, beyond what would be fair compensation for the emotional harm, is cancellable.

4. Application to A and Y's Agreement and Remand:

The Supreme Court agreed with the High Court's factual assessment that the sums stipulated in the Agreement between A and Y were indeed "unconscionably excessive," considering factors such as the duration of their marriage, the circumstances leading to the divorce, and A's dire financial situation.

However, the High Court had erred in cancelling the entire Agreement. The Supreme Court ruled that the correct approach was to:

- Determine the "appropriate" amount for supportive property division and identify the "unconscionably excessive portion."

- Determine the "appropriate" amount for solatium (the actual damages A should be liable for) and identify any amount agreed "exceeding" that.

- Cancel the Agreement only to the extent of these specifically identified excessive amounts.

- The distribution of A's garnished income between X and Y should then be recalculated based on Y's reduced, legally valid claim amount (after deducting the cancelled portions) relative to X's claim.

Because these specific calculations had not been made, the Supreme Court reversed the High Court's judgment concerning the annulment and remanded the case for this detailed re-assessment.

Significance of the Ruling: Refining the "Fraudulent Act" Doctrine in Divorce Contexts

This 2000 Supreme Court decision significantly refines how the doctrine of fraudulent act cancellation applies to financial settlements made in the context of divorce by an insolvent debtor.

- Clarification for Creditors: It provides a clearer, albeit nuanced, pathway for creditors to challenge suspiciously generous divorce settlements that might unfairly deplete a debtor's assets.

- Protection for Divorcing Spouses (to a degree): It affirms that legitimate and appropriate levels of supportive property division and divorce solatium are generally protected from creditor claims of fraudulent act, even if the paying spouse is insolvent. It is only the "excessive" or "disguised gift" portions that are vulnerable to cancellation. This acknowledges the unique nature and social importance of financial settlements upon divorce.

- Endorsement of Partial Cancellation: The explicit endorsement of partial cancellation was a key development. It allows courts to make more precise adjustments, annulling only the objectively unjustifiable parts of a divorce settlement rather than striking down an entire agreement if some components are deemed fair.

- Differentiated Approach for Property Division and Solatium: The Court's decision to apply slightly different standards and rationales for assessing the cancellability of supportive property division versus solatium is noteworthy. Solatium, if representing genuine compensation for wrongdoing, is treated more like the acknowledgment of an existing debt, whereas property division (especially supportive elements) might be more susceptible to being found "unconscionably excessive" if it severely prejudices creditors without strong justification based on need or contribution.

It's also important that the Supreme Court agreed with the High Court that the A-Y Agreement was not a "fictitious transaction" (meaning there was a real intent to create the obligations, even if the amounts were problematic), but rather a genuine agreement whose terms were being challenged as unfair to creditors.

Ongoing Considerations

While this ruling provides significant guidance, the practical application still involves complex factual assessments by the courts. Determining what constitutes an "unconscionably excessive" amount for supportive property division or the "appropriate" level of solatium in any given divorce case remains a highly fact-dependent exercise, taking into account the specifics of the marriage, the reasons for divorce, the financial situations of both spouses, and the needs of any children.

Furthermore, the interaction between these rules for cancelling agreements to pay and the rules for cancelling actual payments already made pursuant to such agreements can present further complexities, especially in formal bankruptcy proceedings where creditor equality principles are paramount. The legal commentary on this case suggests that while an agreement for an appropriate amount might not be a fraudulent act, the actual payment could still be challenged under certain conditions if made with intent to harm creditors while insolvent. This 2000 Supreme Court decision focused on an unpaid agreement affecting a distribution plan for garnished funds, a specific context that may not cover all scenarios of actual asset transfer.

Conclusion: Balancing Creditor Rights with Divorce Realities

The Supreme Court of Japan's March 2000 decision offers a refined framework for balancing the legitimate claims of creditors against the equally legitimate financial needs and entitlements arising from divorce settlements, particularly when the paying spouse is insolvent. By distinguishing between supportive property division and solatium, and by endorsing the principle of partial cancellation for excessive amounts, the Court sought to achieve a more nuanced and equitable outcome. This ruling protects creditors from clear attempts to shield assets through unreasonably generous divorce payouts, while simultaneously respecting the validity of fair and appropriate financial provisions made to support a former spouse or to compensate for the emotional harm of a marriage's end. It underscores the judiciary's role in ensuring that even in the difficult circumstances of insolvency and divorce, financial dispositions are subject to principles of fairness towards all affected parties.