Divorce and Mental Illness in Japan: A 1970 Supreme Court Case on 'Concrete Arrangements' for an Ailing Spouse

Date of Judgment: November 24, 1970

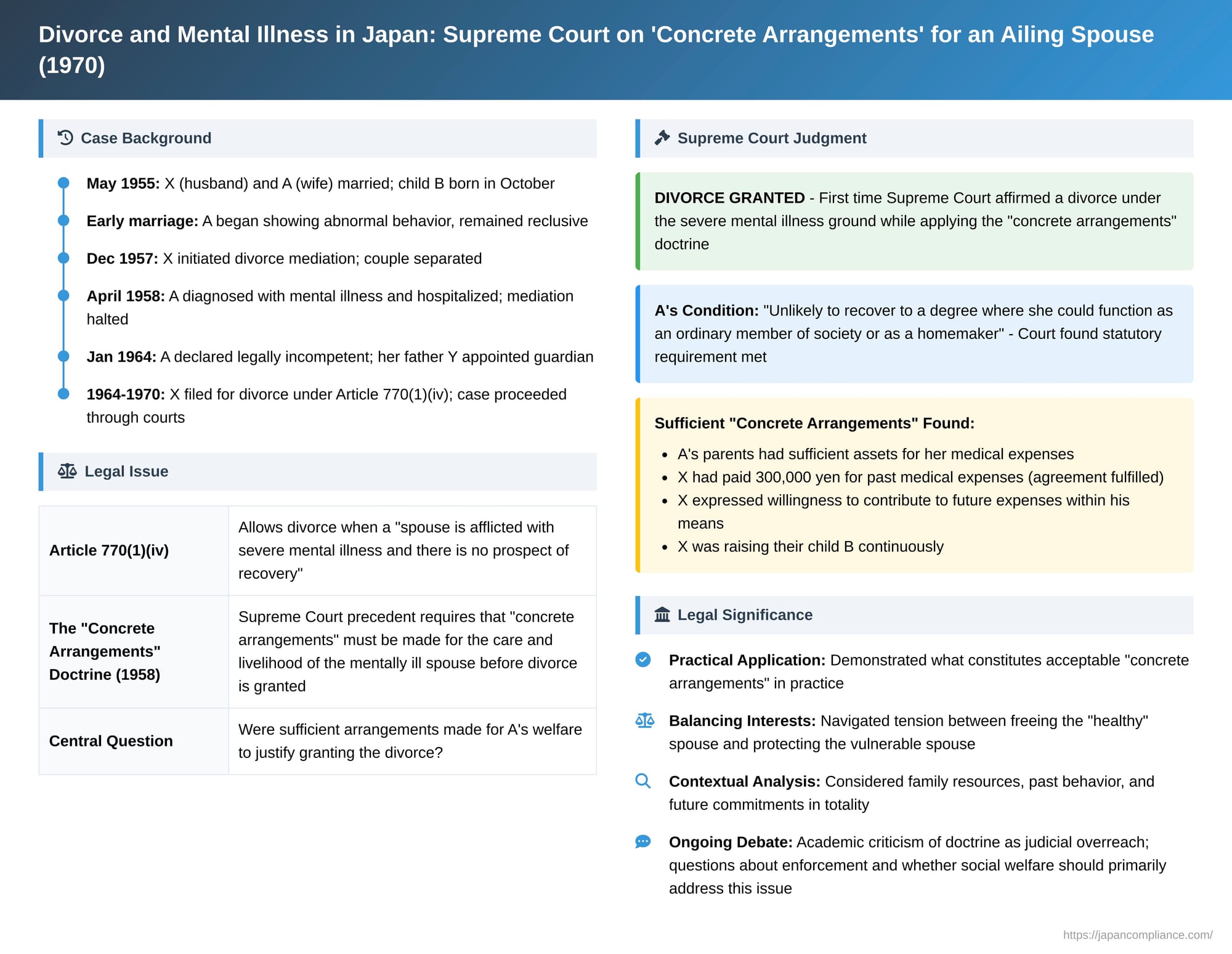

Japanese Civil Code Article 770, paragraph 1, item (iv) provides a specific ground for judicial divorce: when a "spouse is afflicted with a severe mental illness and there is no prospect of recovery." While this provision acknowledges that such profound illness can lead to the irretrievable breakdown of a marital relationship, it also raises significant ethical and social concerns about the welfare of the afflicted spouse post-divorce. Recognizing this dilemma, the Supreme Court of Japan, in a pivotal 1958 precedent, established what is known as the "concrete arrangements" (具体的方途 - gutaiteki hōto) doctrine. This doctrine essentially states that a divorce on this ground should not be granted unless all possible measures for the future care and livelihood of the mentally ill spouse have been considered and some prospect for their well-being is established. The Supreme Court decision of November 24, 1970 (Showa 45 (O) No. 426), provides a crucial illustration of how this doctrine is applied in practice, marking the first time the highest court actually granted a divorce under these stringent conditions.

The Facts of the Case: A Marriage Undone by Illness and Deteriorating Relations

The case involved a husband, X, and his wife, A, who married on May 21, 1955. Their child, B, was born later that year, on October 15. According to the case facts, A began exhibiting abnormal behavior from the early stages of the marriage. Despite efforts to improve the situation, such as relocating, A remained reclusive, struggled to interact with neighbors and the employees of X's newspaper delivery business, and showed no interest or cooperation in X's work.

The marital relationship deteriorated to the point where, on December 21, 1957, X initiated divorce mediation proceedings with the Osaka Family Court, and the couple began living separately. The mediation was reportedly nearing a settlement, which included X paying A 250,000 yen as solatium (damages for emotional distress). However, these proceedings were halted when, on April 8, 1958, A was diagnosed with a mental illness and hospitalized. Consequently, X withdrew the mediation petition.

A's condition saw temporary improvement leading to a discharge, but she was subsequently re-hospitalized. In January 1964, the Osaka Family Court declared A legally incompetent (禁治産宣告 - kinchisan senkoku, an older legal status similar to current adult guardianship), and her father, Y, was appointed as her guardian. A was diagnosed with schizophrenia (at the time referred to as seishin bunretsubyō). Her attending physician indicated that recovery would be a lengthy process, a relapse was highly possible even if she were to be discharged, and it was unpredictable whether she could ever recover sufficiently to resume her role as a homemaker.

Given this situation, X filed a lawsuit for divorce against A (with Y acting as her legal representative), basing his claim on Civil Code Article 770(1)(iv) – that his spouse was afflicted with a severe mental illness with no prospect of recovery.

The first and second instance courts both ruled in favor of X, granting the divorce. Y, acting as A's guardian, appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing two main points: first, that A's mental illness had not reached an incurable stage, and second, that the lower courts' decision to grant the divorce violated the principles set forth in the Supreme Court's 1958 precedent concerning "concrete arrangements" for the ill spouse's future.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Divorce Granted, Applying the "Concrete Arrangements" Doctrine

The Supreme Court dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding the divorce. Its reasoning addressed both of Y's key arguments:

1. Confirmation of "Severe and Incurable Mental Illness":

The Court concurred with the lower courts' assessment of A's condition. It found that A was "unlikely to recover to a degree where she could function as an ordinary member of society or as a homemaker." Therefore, the statutory requirement of a "severe mental illness... [with] no prospect of recovery" under Article 770(1)(iv) was deemed to be met. This involves a legal evaluation by the judge, based on medical expert evidence, focusing not just on the diagnosis but on the severity in terms of impacting the ability to fulfill spousal duties, and the incurability in the sense of no foreseeable return to such a functional state.

2. Applying the "Concrete Arrangements" Doctrine from the 1958 Precedent:

The Court explicitly referenced its 1958 (Showa 33) precedent, which established that even if the conditions of Article 770(1)(iv) are met, a divorce should not be granted unless "all possible concrete measures have been taken for the future medical care, livelihood, etc., of the afflicted spouse, and some prospect for these measures is established." The 1958 ruling had remanded a case where divorce was granted without such considerations, effectively adding this as a crucial judicial check.

The 1970 Court then meticulously examined whether such "concrete arrangements" were sufficiently in place for A:

- A's Family's Financial Resources: The Court noted that A's natal family (her parents) possessed sufficient assets to cover her medical expenses without needing to rely financially on X. This meant that A's basic care was not solely dependent on X's contributions post-divorce.

- X's Past Financial Contributions: Despite X's own limited financial means, he had entered into a formal agreement with Y (A's father and guardian) on April 5, 1965. In this agreement, X committed to paying 300,000 yen to cover A's past medical expenses and other costs incurred since the onset of her illness in April 1958. X had honored this agreement, paying an initial sum of 150,000 yen immediately and the remaining balance by January 1966. Y had accepted these payments without objection.

- X's Stated Intent for Future Contributions: During conciliation attempts at the appellate court stage of the current divorce proceedings, X had expressed his willingness to contribute to A's future medical expenses to the extent that his financial capacity would allow.

- Care of the Child: The Court also took into account that X had been continuously raising their daughter, B, since her birth.

Based on these specific circumstances, the Supreme Court concluded: "These various circumstances signify the absence of grounds that would make the dissolution of the marital relationship inappropriate and thus disallow the divorce claim, as referred to in the aforementioned [1958] precedent." Even considering A's unfortunate illness, the Court found that "this is not a case where the continuation of the marriage between X and A should be deemed appropriate." Consequently, the lower court's decision to grant the divorce under Article 770(1)(iv) was upheld as justifiable.

This judgment was significant as it was the first time the Supreme Court itself, while applying the "concrete arrangements" doctrine established in 1958, actually affirmed the granting of a divorce. It provided a tangible example of what might constitute sufficient arrangements.

The "Concrete Arrangements" Doctrine: Its Purpose, Application, and Critiques

The "concrete arrangements" doctrine, born from the 1958 Supreme Court decision, is an attempt to navigate the difficult ethical terrain of divorces involving severe, incurable mental illness.

- Purpose: It stems from a judicial interpretation of Article 770, paragraph 2 of the Civil Code, which grants courts the discretion to deny a divorce even if one of the statutory grounds (like incurable mental illness) is met, if the court deems that continuing the marriage is appropriate considering all circumstances. The 1958 Court used this discretionary power to ensure that a mentally ill spouse, who is not at fault for their condition, is not left destitute or without necessary care as a result of the divorce. It aims to balance the "healthy" spouse's interest in being freed from a marriage that has effectively broken down due to illness, with the societal and ethical responsibility to protect the vulnerable, afflicted spouse.

- Academic Criticisms: The doctrine has faced considerable academic criticism:

- Overextension of Judicial Discretion: Critics argue that Article 770(2) is intended as a negative discretion – to deny a divorce if there are strong reasons to maintain the marriage despite the existence of a divorce ground. They contend it should not be used to impose positive conditions for granting a divorce, such as making specific financial arrangements.

- Lack of Enforcement Mechanisms: If a court makes a divorce conditional upon certain future financial provisions, there are limited procedural guarantees to ensure these "arrangements" are actually fulfilled post-divorce.

- Misplaced Burden on Divorce Law: Many scholars argue that the financial support and care of individuals with severe mental illnesses should primarily be the responsibility of the social welfare system (e.g., public assistance, disability benefits) and should be addressed through divorce-specific financial settlements like property division or alimony, rather than by making it a threshold condition for the divorce itself under general judicial discretion. Using divorce law as a substitute for robust social security is seen as problematic.

- Despite these criticisms, some commentators expressed understanding for the doctrine, given the potentially inadequate social support systems for the mentally ill at the time, which could leave them vulnerable if divorced without specific provisions.

- The 1970 Ruling's Interpretation of "Concreteness": The 1970 Supreme Court decision's acceptance of X's "willingness to pay within his capacity" for future expenses, coupled with his past fulfillment of financial obligations and the fact that A's family had independent means, has been interpreted in different ways. Some see it as a pragmatic softening of the "concrete arrangements" requirement, possibly influenced by the academic critiques, suggesting that a stringent, legally enforceable guarantee of lifelong support is not always demanded. Others argue that the Court still considered the overall picture, including X's past responsible behavior and A's family's financial independence, to infer a credible commitment from X, thus maintaining a substantive, albeit context-dependent, standard for the "arrangements."

Evolution and Current Relevance of the Doctrine

The legal and social landscape surrounding mental illness and divorce has continued to evolve since 1970.

- Advances in Mental Healthcare: Due to progress in psychiatric medicine and treatment, a diagnosis of "incurable severe mental illness" leading to a complete inability to function maritally is reportedly less common today for conditions like schizophrenia. Consequently, divorce cases involving mental health issues may now more frequently be brought under Article 770(1)(v) – "any other grave reason for which it is difficult to continue the marriage" – rather than the specific mental illness clause. For instance, dementia in elderly spouses is increasingly a factor in divorce under this latter, more general ground.

- Legislative Reform Proposals: A 1996 Civil Code reform proposal suggested deleting Article 770(1)(iv) altogether, aiming to avoid potential discrimination and integrate such cases into the general category of marital breakdown. However, it was anticipated that even under such a reform, courts would likely continue to consider the need for "concrete arrangements" for a vulnerable spouse under their general discretion when assessing whether to grant a divorce.

- Shifting Social Welfare Paradigms: There has been a broader societal shift towards de-familialization of care for the elderly and disabled, with greater emphasis on social support systems. Changes in mental health welfare laws, such as the 2013 abolition of the spousal "protector" (保護者 - hogosha) system which placed significant responsibilities on family members, also reflect this trend. These developments continue to raise questions about the contemporary relevance and appropriate application of the "concrete arrangements" doctrine, which traditionally placed a heavy emphasis on spousal and familial support.

- Remaining Theoretical Questions: A point of contention that remains is the doctrine's differential application. It is a specific consideration for divorces sought on grounds of mental illness but does not typically apply with the same force to cases involving severe physical disability, even if the resulting hardship and need for care for the afflicted spouse are comparable. This raises questions of consistency and fairness in the broader context of divorce law.

Conclusion: A Balancing Act in Difficult Circumstances

The Supreme Court of Japan's 1970 decision in this case was a significant moment in the application of the "concrete arrangements" doctrine. It affirmed that a divorce could indeed be granted on the grounds of a spouse's incurable mental illness, but only after a careful examination of the provisions made for the future well-being of the afflicted spouse. The Court demonstrated a degree of flexibility, considering the specific financial and family circumstances of all parties involved—including the resources of the ill spouse's natal family and the healthy spouse's past conduct and future commitments.

This ruling, and the doctrine it applied, reflects the judiciary's ongoing effort to navigate the challenging intersection of marriage breakdown, individual autonomy, and the societal and ethical responsibilities towards vulnerable individuals. While the specific statutory ground of incurable mental illness might be invoked less frequently today, the underlying principles of balancing competing interests and ensuring a measure of protection for an afflicted spouse in the context of divorce continue to resonate in Japanese family law.