Divorce Across Borders: How Japan's Supreme Court Established Jurisdiction When a Spouse is Missing

Date of Judgment: March 25, 1964

Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench

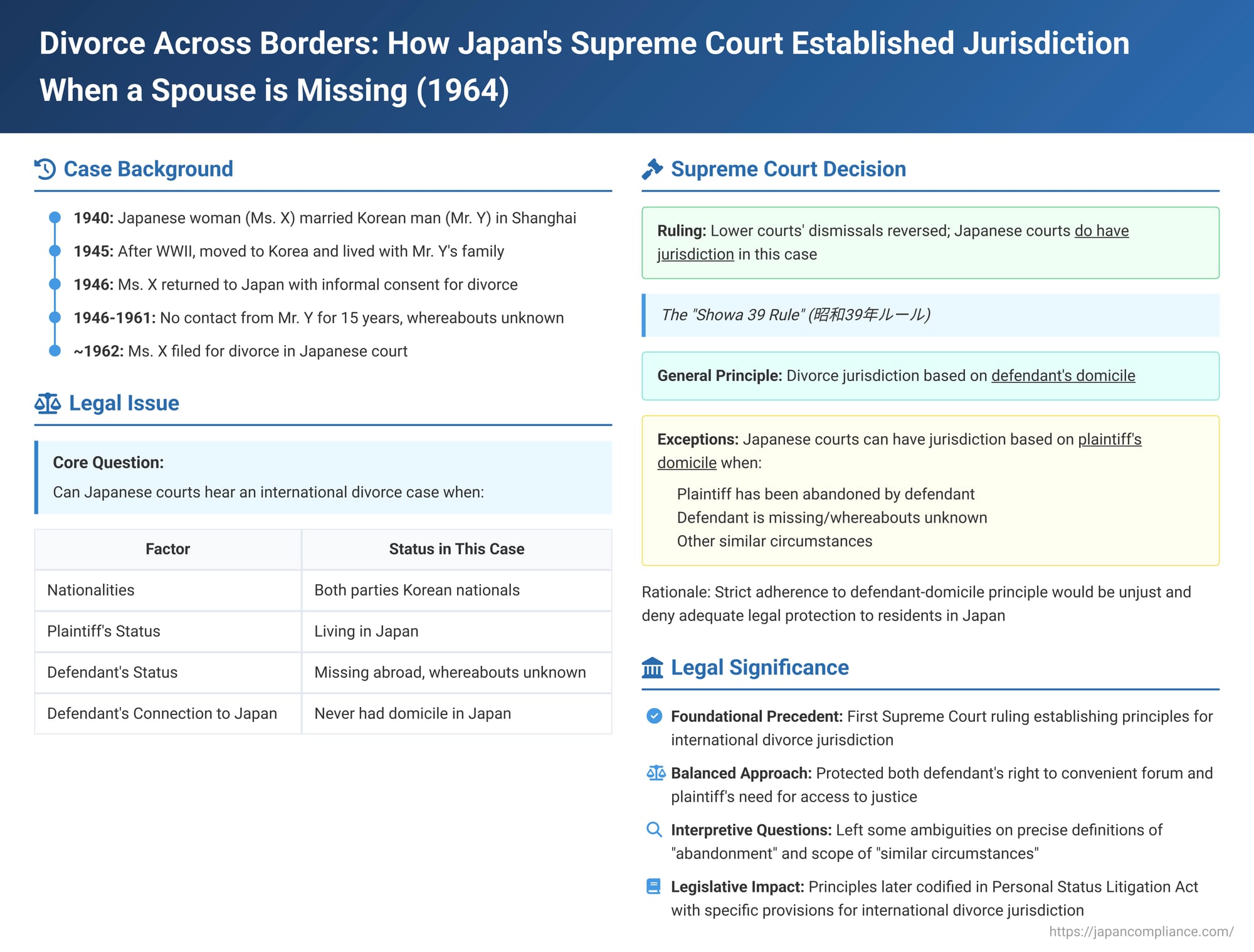

Obtaining a divorce can be complicated, but when international elements are involved—such as differing nationalities or a spouse residing abroad, especially if their whereabouts are unknown—the preliminary question of which country's courts even have the authority to hear the case becomes paramount. A landmark decision by the Grand Bench of the Japanese Supreme Court on March 25, 1964, provided a foundational ruling on international adjudicatory jurisdiction in divorce cases, particularly addressing situations where the defendant spouse is missing. This ruling, often referred to as the "Showa 39 Rule," shaped Japanese law for decades.

The Factual Background: A Marriage Across Cultures and a Disappearing Spouse

The case involved a woman, Ms. X (the plaintiff), and her husband, Mr. Y (the defendant):

- Ms. X was originally a Japanese citizen, born in Tokushima City in 1917. In September 1940, she married Mr. Y, a Korean national, in Shanghai, then within the Republic of China. (Upon this marriage, under the prevailing laws, Ms. X was entered into the Korean family register and, at the time of the lawsuit, both parties were considered to be Korean nationals, Japan having lost its former territorial scope and nationality laws having changed post-WWII).

- After their marriage, the couple lived together in Shanghai. Following the end of World War II in August 1945, they moved to Mr. Y's home country, Korea, and lived with his family.

- Ms. X found it difficult to adapt to life with Mr. Y's family due to significant differences in customs and environment. With Mr. Y's de facto (though not formally legal) consent to a divorce, Ms. X left Korea and returned to Japan alone in December 1946.

- After Ms. X's return to Japan, Mr. Y never made any contact with her. His whereabouts became unknown, and 15 years passed without any news from him.

- Consequently, Ms. X, residing in Japan, filed for divorce in a Japanese court. She based her claim on grounds recognized under Korean family law, specifically Article 840(5) (if the spouse's life or death has been unknown for three years or more) and Article 840(6) (if there is any other serious cause making it difficult to continue the marriage).

The Takamatsu District Court (first instance) and the Takamatsu High Court (second instance) both dismissed Ms. X's lawsuit. They reasoned that for divorce cases between foreign nationals, even if the plaintiff resides in Japan, Japanese courts should only assume jurisdiction if, at a minimum, the defendant had their last domicile in Japan. Since Mr. Y had never resided in Japan, granting jurisdiction would effectively deny him the ability to respond and was deemed improper. Ms. X appealed this dismissal to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Question: Do Japanese Courts Have Jurisdiction Over a Divorce When Both Parties Are Foreign Nationals and the Defendant is Missing Abroad?

The central issue for the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court was whether Japanese courts could exercise international adjudicatory jurisdiction in a divorce case where both spouses were foreign nationals, the plaintiff resided in Japan, and the defendant husband's whereabouts had been unknown for many years, with no prior domicile in Japan.

The Supreme Court's Landmark "Showa 39 Rule"

The Supreme Court quashed the lower courts' judgments and transferred the case to the Tokyo District Court (deeming it the proper domestic venue if Japan had jurisdiction). In its reasoning, the Court established what became known as the "Showa 39 Rule" (named after the Japanese imperial era year corresponding to 1964):

- Principle of Defendant's Domicile: The Court acknowledged that, as a general principle, international adjudicatory jurisdiction in divorce cases should be based on the defendant's domicile being in Japan. This general rule, the Court stated, aligns with the requirements of procedural justice and also helps to avoid the creation of "limping marriages" (跛行婚 - hakōkon)—marriages that are considered dissolved in one country but still valid in another.

- Exceptions Based on Plaintiff's Domicile in Japan: Crucially, however, the Supreme Court carved out important exceptions to this general principle. It ruled that Japanese courts could exercise jurisdiction based on the plaintiff's domicile being in Japan, even if the defendant was not domiciled there, under certain specific circumstances. These circumstances include cases where:

- The plaintiff has been abandoned (遺棄 - iki) by the defendant.

- The defendant is missing (行方不明 - yukue fumei), meaning their whereabouts are unknown.

- Other similar circumstances exist.

- Rationale for the Exceptions: The Court reasoned that rigidly adhering to the defendant-domicile principle in these exceptional situations would be unjust. It would mean denying adequate legal protection to individuals (including foreigners) residing in Japan who might have valid grounds for divorce recognized even under Japanese law (referencing the old Horei Article 16 proviso, which concerned applicable law in international marriages). Such a rigid approach would lead to outcomes contrary to the ideals of justice and fairness in international private law.

- Application to Ms. X's Case: Given that Ms. X's divorce claim was based on the alleged circumstances (including Mr. Y's prolonged disappearance), and since Ms. X had been domiciled in Japan continuously since December 1946, the Supreme Court concluded that it was appropriate for Japanese courts to exercise jurisdiction over her divorce lawsuit, even though Mr. Y had never had a domicile in Japan.

Significance and Evolution of the "Showa 39 Rule"

This 1964 Grand Bench decision was the first time the Japanese Supreme Court had laid down principles for international divorce jurisdiction. It became a foundational precedent:

- Established Case Law: The "Showa 39 Rule" was quickly followed in subsequent Supreme Court cases and was widely accepted as the established case law governing international divorce jurisdiction in Japan for many years, until more specific legislative rules were enacted.

- Balancing Competing Interests: The rule attempted to strike a balance between the defendant's right to a convenient forum (typically their place of domicile) and the plaintiff's need for access to justice, especially when facing situations like abandonment or a spouse's disappearance.

- Unresolved Issues and Subsequent Debates: While groundbreaking, the "Showa 39 Rule" left some ambiguities that led to considerable academic discussion and varied interpretations in lower courts over the years. These included:

- The precise definition of "abandonment" (e.g., did it cover being abandoned abroad before coming to Japan?).

- The required duration for a spouse to be considered "missing."

- The scope of "other similar circumstances" (e.g., did it include cases where the defendant appeared and consented to Japanese jurisdiction, or situations where a foreign divorce was unobtainable or would not be recognized in Japan?).

- The role, if any, of the parties' nationality as a basis for jurisdiction (referred to as "national jurisdiction" - 本国管轄, honkoku kankatsu). While the Showa 39 case involved foreign nationals, the judgment's focus on domicile and the specific exceptions left the role of nationality somewhat open to interpretation, though it was generally not seen as a primary independent ground for jurisdiction by later courts or scholars without other connections to Japan.

- Influence on Later Legislation: The principles established by the "Showa 39 Rule," along with those from a subsequent key Supreme Court ruling in 1996 (the "Heisei 8 Rule," which further clarified jurisdiction when foreign divorce decrees were not recognized), heavily influenced the drafting and eventual enactment of specific statutory provisions on international jurisdiction for divorce cases within Japan's Personal Status Litigation Act (PSLA).

Current Law: Codification in the Personal Status Litigation Act

Today, international adjudicatory jurisdiction for divorce and other personal status matters in Japan is governed by specific articles within the Personal Status Litigation Act (primarily Articles 3-2 onwards, as amended). These codified rules reflect and build upon the principles developed in the "Showa 39 Rule" and subsequent case law. The PSLA now provides clearer bases for jurisdiction, including:

- Defendant's domicile in Japan.

- Plaintiff's domicile in Japan under specified conditions (such as the defendant being missing, or if necessary for fairness or prompt trial, or if the couple's last common domicile was in Japan).

- Common Japanese nationality of both spouses.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1964 decision in this case was a landmark judgment that established a vital framework for international divorce jurisdiction in Japan at a time when specific statutory guidance was lacking. By recognizing the defendant's domicile as the primary basis for jurisdiction but allowing for crucial exceptions based on the plaintiff's domicile in situations of hardship such as abandonment or a spouse's disappearance, the "Showa 39 Rule" provided a path to justice for individuals residing in Japan who might otherwise have been left without a forum to resolve their marital status. This ruling's principles have had a lasting impact, shaping the discourse and ultimately the legislative framework for international family law jurisdiction in Japan.