Dissecting Pay Disparities: The Hamakyorex Supreme Court Ruling on Fixed-Term vs. Permanent Employees in Japan

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of June 1, 2018 (Case Nos. 2016 (Ju) No. 2099 & No. 2100: Claim for Unpaid Wages, etc.)

Appellant/Appellee (Employer): Y Company

Appellee/Appellant (Employee): X

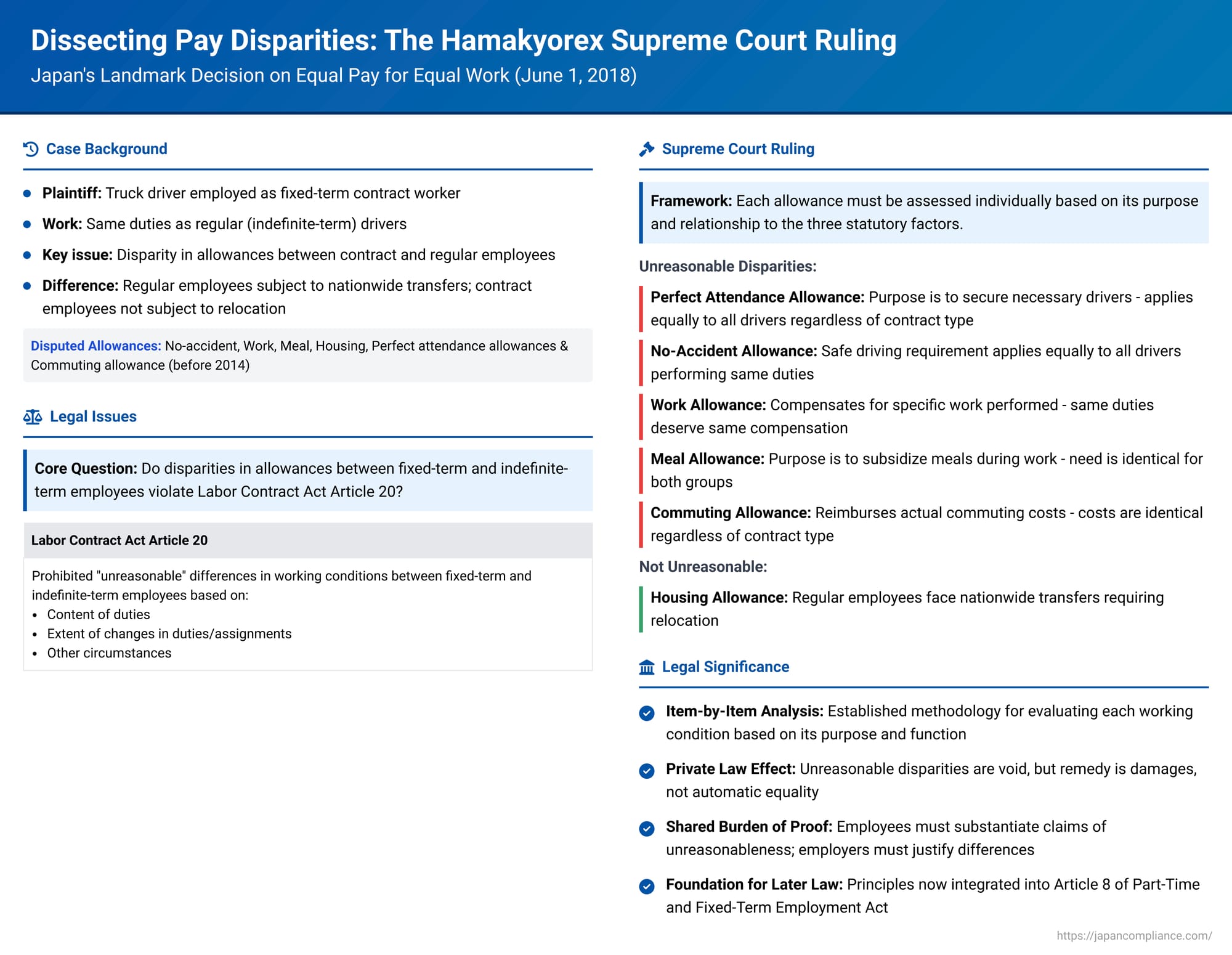

On June 1, 2018, the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a landmark judgment in the Hamakyorex case, a decision with profound implications for the treatment of fixed-term contract employees compared to their permanent counterparts. This case meticulously examined various differences in allowances and benefits under the now-former Article 20 of Japan's Labor Contract Act (LCA), which prohibited unreasonable disparities in working conditions based on the fixed-term nature of an employment contract. While Article 20 has since been integrated into Article 8 of the Part-Time and Fixed-Term Employment Act (PTFTA), the principles enunciated in Hamakyorex continue to shape the legal discourse on "equal pay for equal work" in Japan.

Setting the Scene: The Facts of Hamakyorex

The plaintiff, X, was a truck driver working for Y Company, a transportation firm, at its A branch (referred to as the Hikone branch in the judgment text). X was employed under a fixed-term labor contract that had been renewed multiple times. His compensation was primarily an hourly wage (initially ¥1150, later ¥1160) and a commuting allowance of ¥3000 per month. As a contract employee, he generally did not receive regular pay raises or bonuses.

In contrast, Y Company's regular employees (those with indefinite-term contracts) had a monthly salary structure, with basic pay composed of age-based pay, length-of-service pay, and function-based pay. They were also eligible for a range of allowances and benefits not available, or available on different terms, to contract employees like X. Separate sets of work rules and salary regulations governed regular and contract employees.

Crucially, the Supreme Court acknowledged the lower court's finding that the actual job duties and the degree of responsibility associated with the truck driving work performed by X and the regular employees at the A branch were the same.

However, there were differences in the broader scope of their employment:

- Regular Employees: Faced the possibility of nationwide transfers, including secondment to other companies. They were part of a formal grading and job-ranking system designed for fair treatment, appropriate placement, ongoing training, and development as core human resources for the company.

- Contract Employees (like X): Had no expectation of changes to their work location or secondments. They were not included in the company's formal human resource development and career progression systems for regular employees.

The dispute centered on the differences in the following specific allowances and benefits:

- No-accident allowance: Provided to regular employees (¥10,000/month for accident-free work) but not to contract employees.

- Work allowance: Provided to regular employees for engaging in specific duties (¥10,000/month at the A branch) but not to contract employees.

- Meal allowance: Provided to regular employees (¥3,500/month) but not to contract employees.

- Housing allowance: Provided to regular employees (¥5,000/month for those 21 or younger, ¥20,000/month for those 22 or older) but not to contract employees.

- Perfect attendance allowance: Provided to regular employees (¥10,000/month for perfect attendance on all workdays) but not to contract employees.

- Commuting allowance (until December 2013): X received ¥3,000/month, while a regular employee with the same commuting arrangements would have received ¥5,000/month. This was equalized from January 2014.

- Family allowance: Available to regular employees but not to contract employees.

- Bonus: Generally not provided to contract employees (though possible based on company/individual performance), while regular employees received bonuses based on company performance.

- Regular pay raise: Generally not provided to contract employees (though possible based on company/individual performance), while regular employees had them as part of their pay structure.

- Retirement allowance: Generally not provided to contract employees, while regular employees were eligible after five or more years of service.

X argued that these differences constituted a violation of former Article 20 of the Labor Contract Act. He sought a court declaration that he held the same rights as regular employees concerning these benefits, payment of the difference in allowances for a specified period, and, alternatively, damages in tort for the unlawful disparities.

The Legal Framework: Former Labor Contract Act Article 20

Former Article 20 of the LCA stated that where working conditions differ between a worker with a fixed-term labor contract and a worker with an indefinite-term labor contract with the same employer, such difference shall not be found unreasonable if it is due to the contract having a fixed term, taking into account (i) the content of the worker's duties, (ii) the extent of changes in the content of duties and assignment, and (iii) other circumstances.

The core aim of this provision was to address the growing societal concern over disparities between regular (permanent) and non-regular (fixed-term) employees by prohibiting "unreasonable" differences linked to the contractual term.

The Supreme Court's Interpretation and Rulings

The Supreme Court's judgment in Hamakyorex provided extensive interpretation of former LCA Article 20 and meticulously applied it to each contested allowance.

1. Purpose and Effect of (Former) Article 20:

- Purpose - Balanced Treatment, Not Automatic Equality: The Court clarified that Article 20 aimed to ensure fair treatment for fixed-term contract workers by prohibiting unreasonable working conditions that arise due to the contract having a fixed term. It acknowledged that differences in working conditions between fixed-term and indefinite-term employees could exist. The provision's objective was to ensure that such differences were not "unreasonable" when considering the job content, the scope of changes in job duties and assignments, and other relevant circumstances. It sought "balanced treatment" appropriate to any such differences, rather than mandating strict equality in all instances.

- Private Law Effect - Voidness, Not Automatic Equalization: The Court affirmed that Article 20 has a direct effect on private law. This means that any part of a fixed-term labor contract establishing a difference in working conditions that violates Article 20 is null and void. However, this voidness does not automatically elevate the working conditions of the fixed-term employee to be identical to those of the comparable indefinite-term employee. The Court noted that Y Company had separate and distinct work rules and salary regulations for regular employees and contract employees. Therefore, simply because a difference was deemed unreasonable under Article 20, it did not mean that the regular employees' work rules or salary regulations would automatically apply to X. Consequently, X's primary claims for confirmation of identical rights and direct payment of wage differences based on that premise were dismissed. The primary remedy for a breach of Article 20, leading to such void provisions, is a claim for damages in tort.

2. Applicability of Article 20 – "Due to the existence of a fixed term":

The Court interpreted the phrase "due to the existence of a fixed term" (「期間の定めがあることにより」) as meaning that the difference in working conditions between fixed-term and indefinite-term employees is related to the presence or absence of a fixed term. The Court suggested that the degree of this connection is a factor to be considered when assessing the unreasonableness of the difference, rather than a strict, high-bar causation requirement. In this case, given that distinct work rules applied to contract employees and regular employees, the resulting differences in allowances were considered to be related to the fixed-term nature of X's contract and thus fell within the ambit of Article 20.

3. Defining "Unreasonable" and the Burden of Proof:

- "Unreasonable" as an Evaluable Standard: The Supreme Court stated that the term "unreasonable" in Article 20 means that the difference in working conditions can be evaluated as unreasonable. This is a normative assessment, not merely a statement of something not being rational.

- Shared Burden of Proof: In making this normative evaluation, the burden of proof is shared. The party alleging a violation of Article 20 (typically the fixed-term employee) is responsible for proving the facts that would support an evaluation of unreasonableness. Conversely, the party disputing the violation (typically the employer) is responsible for proving facts that would negate such an evaluation (i.e., facts that support the reasonableness of the difference).

- Respect for Employer Discretion and Negotiations: The Court also noted that in assessing whether working conditions are "balanced," aspects of labor-management negotiations and the employer's business judgment should be given a degree of respect.

4. Item-by-Item Analysis of Allowances – The Heart of the Judgment:

The Supreme Court then undertook a detailed, item-by-item examination of each disputed allowance, considering the purpose of each allowance and the actual differences in job duties, scope of changes, and other circumstances between X and the regular employees.

- Housing Allowance (Difference: Not Unreasonable):

- Purpose: To subsidize employees' housing costs.

- Reasoning: Regular employees at Y Company were subject to potential nationwide transfers, including those requiring relocation, which could lead to higher housing expenses. Contract employees like X, however, were not expected to relocate for work. This difference in potential housing burdens justified the disparity in housing allowance. Thus, providing housing allowance to regular employees but not to contract employees was not deemed unreasonable.

- Perfect Attendance Allowance (Difference: Unreasonable):

- Purpose: To encourage perfect attendance among truck drivers to ensure the smooth operation of Y Company's transportation services by securing a necessary number of available drivers.

- Reasoning: The job duties of X (contract driver) and regular drivers were the same. The necessity of ensuring driver attendance was therefore also the same for both groups and did not differ based on their job content. The potential for regular employees to be transferred or promoted to core positions in the future did not alter this need for present attendance. Furthermore, while X's contract mentioned a possibility of pay raises based on performance, non-raising was the default, and there was no evidence that perfect attendance was considered for such raises. Therefore, denying this allowance to contract drivers while providing it to regular drivers performing the same duties was deemed unreasonable. The Supreme Court overturned the High Court on this point for the period after LCA Article 20 became applicable and remanded the case for a determination of whether X actually met the perfect attendance criteria.

- No-Accident Allowance (Difference: Unreasonable):

- Purpose: To foster the development of skilled, safe drivers and to earn customer trust through safe transportation.

- Reasoning: The job duties of contract and regular drivers were identical. The need for safe driving and accident prevention was consequently the same for both. The fact that regular employees might have future prospects for transfer or promotion did not diminish this shared need for safe operation by all drivers. No other circumstances were found to justify treating contract employees differently in this regard. The difference was thus unreasonable.

- Work Allowance (Difference: Unreasonable):

- Purpose: This allowance was paid for performing specific types of work and was considered monetary compensation for those particular tasks. At the A branch, regular drivers uniformly received ¥10,000.

- Reasoning: X's job duties were the same as those of regular drivers. The different scope of potential future job changes or assignments for regular employees did not alter the monetary value of the actual tasks performed by both groups. No other legitimate reasons were presented to justify the disparity. The difference was held to be unreasonable.

- Meal Allowance (Difference: Unreasonable):

- Purpose: To provide a subsidy for employees' meal expenses. It is logical to provide this to employees who need to take meals during their working hours.

- Reasoning: The job duties of contract and regular drivers were the same, and there was no discernible difference in their work patterns that would affect their need to take meals during work time. The different scope of potential future job changes or assignments for regular employees was irrelevant to the necessity and extent of needing meals during work hours. No other circumstances justified the disparity. The difference was found to be unreasonable.

- Commuting Allowance (Difference before January 2014: Unreasonable):

- Purpose: To reimburse employees for their commuting expenses.

- Reasoning: The actual cost of commuting does not differ based on whether an employment contract is fixed-term or indefinite-term. Differences in the scope of potential job content or assignment changes are not directly related to the amount of commuting expenses incurred. No other circumstances justified the disparity in amounts paid (X received ¥3,000, while a comparable regular employee received ¥5,000). This difference was deemed unreasonable.

(Note: The Supreme Court did not rule on family allowance, bonuses, regular pay raises, or retirement allowance in terms of their unreasonableness under Article 20 in this specific judgment for X, as these were not the primary focus of the final appeal on merits or were handled differently procedurally.)

Significance and Implications of the Hamakyorex Decision

The Hamakyorex judgment is a cornerstone in the evolving jurisprudence on non-regular employment in Japan.

- Framework for "Unreasonableness": It established a clear analytical framework for assessing "unreasonableness" under former LCA Article 20 (and by extension, current PTFTA Article 8). This involves an item-by-item consideration of each working condition, focusing on its nature and purpose, and then evaluating any disparity against the "three elements": job duties, scope of changes in duties and assignments, and other circumstances.

- Remedy is Primarily Damages: The Court clarified that while an unreasonable disparity renders the relevant contract provision void, it doesn't automatically entitle the fixed-term employee to the same conditions as a permanent employee. The principal legal remedy for the employee is damages in tort.

- Guidance on Burden of Proof: It provided crucial guidance on the shared burden of proof, requiring employees to substantiate claims of unreasonableness and employers to justify the differences.

- Continuing Relevance under PTFTA: Although LCA Article 20 has been repealed and its principles absorbed into Article 8 of the Part-Time and Fixed-Term Employment Act, the detailed reasoning in Hamakyorex regarding the purpose of various allowances and the factors determining unreasonableness remains highly influential in interpreting the current law. PTFTA Article 8 similarly prohibits unreasonable differences in treatment between regular employees and part-time/fixed-term employees, considering the nature of the job, etc., and also includes a provision requiring employers to explain differences in treatment if requested by a worker.

- Part of a Larger Trend: Hamakyorex was one of the first major Supreme Court rulings on LCA Article 20, followed by others (e.g., Nagasawa Unyu, and later the "October 2020" series of cases including Osaka Medical University, Metro Commerce, and Japan Post cases ) that have further refined the application of these principles to different benefits like bonuses and retirement allowances, often with varying outcomes depending on the specific facts and the nature of the benefit. These cases collectively underscore that there is no blanket "yes" or "no" to disparities; each element of compensation or working condition must be analyzed individually based on its purpose and the specific circumstances.

Conclusion

The Hamakyorex Supreme Court decision marked a significant step in addressing wage and benefit disparities between fixed-term and permanent employees in Japan. By providing a detailed methodology for evaluating the reasonableness of such differences on an allowance-by-allowance basis, the Court offered both employers and employees critical guidance. While not mandating absolute equality, it firmly established that differences in treatment must be objectively justified based on the nature and purpose of each working condition and the actual circumstances of employment. This judgment continues to be a vital reference point for ensuring fair treatment and compliance with labor laws aimed at protecting non-regular workers.