Dissecting Marks: Japan's Supreme Court on Similarity of Composite Trademarks (Tsutsumi no Ohinakkoya Case)

Judgment Date: September 8, 2008

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 19 (Gyo-Hi) No. 223 (Action for Rescission of a Trial Decision)

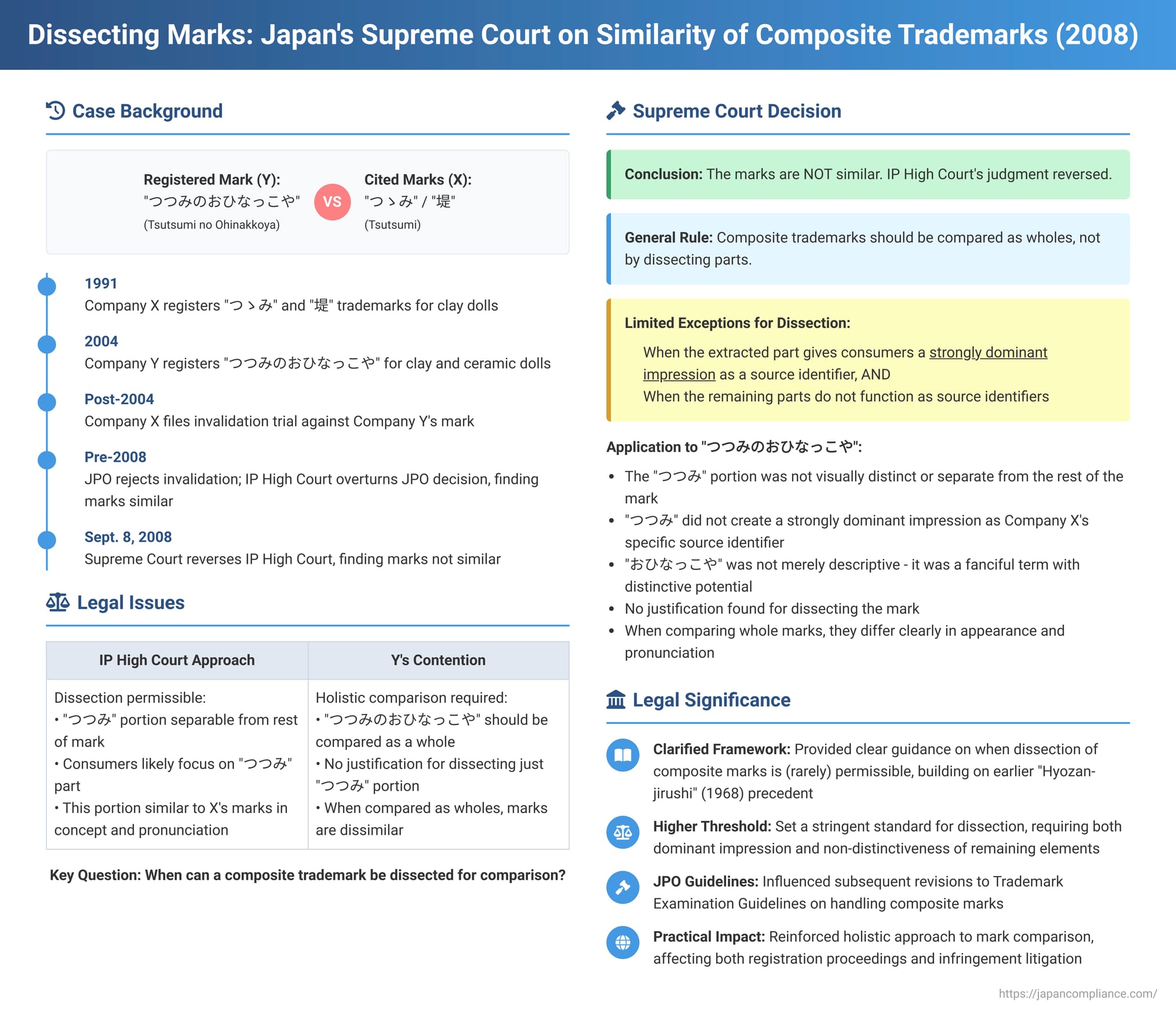

The "Tsutsumi no Ohinakkoya" case, decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 2008, provides critical guidance on a frequently encountered issue in trademark law: how to assess the similarity of composite trademarks. Specifically, the Court addressed when it is permissible to dissect a multi-component trademark and compare only a portion of it with another mark, a practice that can significantly influence the outcome of a similarity analysis. This ruling, referencing and building upon earlier precedents, reinforced a general principle of holistic comparison while outlining narrow exceptions where dissecting a mark might be justified.

The Trademarks and the Dispute

The case involved a dispute between two parties over trademarks used for traditional Japanese dolls.

- Company Y's Trademark (the "Registered Mark"): Company Y (the appellant to the Supreme Court) was the owner of a registered trademark consisting of the Japanese hiragana phrase "つつみのおひなっこや" (Tsutsumi no Ohinakkoya), written horizontally in standard characters. This trademark was registered in 2004 for designated goods including "clay dolls and ceramic dolls". The phrase roughly translates to "Tsutsumi's Little Hina Doll Shop/Place."

- Company X's Trademarks (the "Cited Marks"): Company X (the appellee in the Supreme Court) was the owner of two prior registered trademarks, both registered in 1991 for "clay dolls":

- "つゝみ" (Tsutsumi), written in a slightly older form of the hiragana character 'tsu', in bold horizontal letters.

- "堤" (Tsutsumi), the single kanji character for Tsutsumi (which can mean embankment, and is also used as a place name and surname associated with a traditional type of doll), in bold.

Company X initiated an invalidation trial against Company Y's Registered Mark, arguing, among other things, that it was confusingly similar to its own Cited Marks and therefore violated Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 11 of the Japanese Trademark Law. This provision prohibits the registration of a trademark that is identical or similar to a prior registered trademark used on identical or similar goods.

The Japan Patent Office (JPO) dismissed Company X's invalidation request. The JPO found that the Registered Mark "つつみのおひなっこや" was not similar to either of the Cited Marks ("つゝみ" or "堤"). Company X appealed this JPO decision to the Intellectual Property (IP) High Court.

The IP High Court's Decision: Allowing Dissection

The IP High Court overturned the JPO's decision, concluding that the trademarks were similar. The High Court's reasoning centered on the permissibility of dissecting Company Y's Registered Mark:

- It found that the initial "つつみ" (Tsutsumi) portion of the longer phrase "つつみのおひなっこや" was not so seamlessly integrated with the rest of the mark as to be inseparable in the minds of consumers.

- Given the overall length of the Registered Mark, the High Court reasoned that consumers would likely focus on and separately recognize the initial "つつみ" part.

- From this extracted "つつみ" portion, consumers would derive the concept (kannen) of the place name "Tsutsumi" (known for Tsutsumi dolls), a personal name, or the "Tsutsumi" associated with the dolls themselves. It would also give rise to the pronunciation (shōko) "TSUTSUMI."

- Since Company X's Cited Marks ("つゝみ" and "堤") also evoked the same "Tsutsumi" concept and "TSUTSUMI" pronunciation, the High Court concluded that the Registered Mark and the Cited Marks were similar overall, primarily due to the similarities in concept and pronunciation stemming from this dissectible "つつみ" component. This was despite acknowledging some differences in visual appearance.

Based on this finding of similarity, the IP High Court held that Company Y's Registered Mark should be invalidated under Article 4(1)(xi). Company Y then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Reversal: Guiding Principles on Composite Mark Similarity

The Supreme Court reversed the IP High Court's decision and remanded the case for further consideration (though its reasoning strongly indicated a finding of non-similarity). The Supreme Court's judgment provided a detailed exposition of the principles governing the similarity analysis of composite trademarks.

(1) The General Principle for Trademark Similarity (The Hyozan-jirushi Standard)

The Court began by reiterating the established general principle for assessing trademark similarity, referencing its earlier landmark decision in the Hyozan-jirushi (Iceberg Mark) case (Supreme Court, 1968). Trademark similarity under Article 4(1)(xi) is to be determined by:

- Assessing whether the trademarks, when used on identical or similar goods or services, are likely to cause misidentification or confusion as to the source.

- This assessment must be holistic, considering the overall impression, memory, and associations that the trademarks create for traders and consumers. These impressions are derived from the marks' appearance (外観 - gaikan), concept or idea (観念 - kannen), and pronunciation (称呼 - shōko).

- The analysis must also take into account the actual circumstances of trade (取引の実情 - torihiki no jitsujō) for the relevant goods or services.

(2) The Rule for Composite Trademarks: When Dissection is Generally Impermissible

Building on this general principle, the Supreme Court articulated a specific rule for composite trademarks (結合商標 - ketsugō shōhyō), which are marks made up of multiple components (e.g., words, devices, or combinations thereof):

- As a general rule, when comparing a composite trademark with another mark, it is not permissible to dissect or extract only a part of the composite trademark and compare that isolated part with the other mark to determine the overall similarity of the trademarks themselves.

- Narrow Exceptions (When Dissection Might Be Permissible): The Court acknowledged that this general rule against dissection is not absolute. Dissection might be allowed in limited circumstances, such as:

- Where the extracted portion, by itself, gives traders and consumers a strongly dominant impression as a source-identifying mark (出所識別標識 - shussho shikibetsu hyōshiki).

- Where the remaining parts of the composite trademark (i.e., those parts not extracted) do not give rise to any source-identifying pronunciation or concept.

The Supreme Court cited two of its previous rulings in support of this framework: the Rira Takarazuka case (December 5, 1963) and the SEIKO EYE case (September 10, 1993).

(3) Applying the Principles to the "Tsutsumi no Ohinakkoya" Marks

The Supreme Court then meticulously applied these principles to the facts of the case:

- Appearance of "つつみのおひなっこや": The Court observed that while the Registered Mark contained the letters "つつみ" (which, when pronounced, is the same as the Cited Marks), the full mark "つつみのおひなっこや" was presented in standard characters of uniform size and font, arranged neatly in a single, continuous line. Critically, the Court found that the "つつみ" portion was not configured in such a way as to independently catch the viewer's attention or stand out from the rest of the phrase.

- Assessing the "つつみ" Portion as a Dominant Source Identifier:

- The Court acknowledged the historical context: Tsutsumi dolls, originating from Tsutsumi Town in Sendai City (堤町 - Tsutsumi-chō), were well-known among traders of the designated goods. Thus, the "つつみ" part of the Registered Mark could indeed evoke the concept of the place name "Tsutsumi," a personal name, or the "Tsutsumi" associated with these traditional dolls.

- However, the Court found no evidence that, at the time of the JPO's decision, this "つつみ" portion—beyond its general association with the geographical origin or type of doll—gave traders and consumers a strongly dominant impression that Company X (the owner of the Cited Marks) was the specific source of the designated clay and ceramic dolls. The Court noted that Company Y's grandfather had started producing Tsutsumi dolls by 1981, well before Company X's Cited Marks were registered in 1991.

- Assessing the Source-Identifying Function of the "おひなっこや" (Ohinakkoya) Portion:

- The Court considered that traders and consumers encountering the "おひなっこや" portion would likely understand it as referring to a business involved in the manufacture or sale of Hina dolls ("おひな" - ohina, a term for Hina dolls) or related items ("っ子" - kko, a diminutive or familiar suffix; "や" - ya, often indicating a shop or proprietor).

- However, the Court found that "おひなっこや" was not a generally used or common term for a "Hina doll shop". Instead, it would typically be understood as a newly coined or fanciful term.

- Therefore, this "おひなっこや" part could not be dismissed as merely generic or descriptive in direct relation to clay dolls and lacking any capacity to identify source. It possessed its own potential for distinctiveness.

- No Justification for Dissection: The Supreme Court concluded that there were no other circumstances that would justify dissecting the "つつみ" portion from the rest of the mark "つつみのおひなっこや" for the purpose of comparison.

- Holistic Comparison Mandated: Consequently, the similarity between the Registered Mark and the Cited Marks had to be determined by comparing their entire compositions. It was impermissible to isolate the "つつみ" part of the Registered Mark and compare only that part with Company X's Cited Marks.

(4) Result of the Holistic Comparison:

When comparing the marks in their entirety, the Supreme Court found:

- The Registered Mark "つつみのおひなっこや" and the Cited Marks ("つゝみ," "堤") shared only the first three (out of ten) characters of the Registered Mark in terms of phonetic value.

- Visually (in appearance) and phonetically (in pronunciation), the marks were clearly different when considered as wholes.

- Even if both the Registered Mark and the Cited Marks could evoke a concept related to "Tsutsumi dolls," this conceptual link alone was insufficient to render them similar overall, given the significant differences in appearance and pronunciation.

Thus, the Supreme Court concluded that the marks were not similar trademarks overall.

Deeper Dive into Composite Mark Analysis and Its Significance

The Tsutsumi no Ohinakkoya decision is a significant reference point for understanding how Japanese law approaches the similarity of composite trademarks.

- Building on Precedent: The judgment explicitly references and builds upon the Hyozan-jirushi case for the general principles of trademark similarity. It then applies these principles to the specific complexities of composite marks, drawing on earlier Supreme Court rulings like the Rira Takarazuka case (which acknowledged that parts of a loosely combined mark might be separately perceived) and the SEIKO EYE case (which focused on a dominant famous component combined with a generic term).

- The Strict Standard for Dissection: The Tsutsumi no Ohinakkoya ruling is often interpreted as setting a relatively high bar for allowing the dissection of composite marks. It emphasizes that dissection should only occur in exceptional cases where a specific part is overwhelmingly dominant as a source identifier, or where the remaining parts are truly non-distinctive.

- Scholarly Synthesis of Dissection Criteria: Legal commentators, such as the prominent Judge Takabe Makiko (then Chief Judge of the IP High Court), have synthesized the principles from these key Supreme Court decisions. According to this synthesis, dissection of a composite mark may be permissible if:

- (a) The part in question gives traders and consumers a strongly dominant impression as a source-identifying mark (reflecting language from Tsutsumi no Ohinakkoya and SEIKO EYE).

- (b) The other parts of the composite mark do not generate any source-identifying pronunciation or concept (reflecting language from Tsutsumi no Ohinakkoya).

- (c) The constituent parts are not so inseparably linked as to make their separate observation commercially unnatural (reflecting language from Rira Takarazuka).

It's noted that the precise interplay and hierarchy of these criteria are still evolving in judicial practice, with some IP High Court decisions allowing dissection based on criterion (c) even if (a) or (b) are not strongly met, while others may link the criteria.

- Impact on JPO Trademark Examination Guidelines: Following the Tsutsumi no Ohinakkoya decision, the JPO's Trademark Examination Guidelines were revised. The guidelines now state that for composite trademarks, if the constituent parts are not so strongly combined as to make separate observation commercially unnatural (echoing criterion (c)), then a part alone can give rise to a distinct pronunciation or concept. Notably, the specific phrasing of criteria (a) and (b) from the Tsutsumi no Ohinakkoya judgment was not directly incorporated into this section of the guidelines, which instead leaned on the more flexible language from the Rira Takarazuka era.

- Practical Challenges: Despite these judicial pronouncements and guideline revisions, determining whether a composite mark can be dissected remains a case-specific and often complex inquiry. The actual composition of the mark, the nature of its components, the way they are combined, and the relevant trade circumstances all play crucial roles. Practitioners must therefore pay close attention to the ongoing accumulation of case law in this area.

Conclusion

The "Tsutsumi no Ohinakkoya" Supreme Court case serves as a vital reminder of the general principle in Japanese trademark law that composite trademarks should be compared in their entirety. While it acknowledges that there are exceptions where a part of a mark might be isolated for comparison, the Court defined these exceptions narrowly. The decision emphasizes that for dissection to be justified, the isolated part must typically be a strongly dominant source identifier, or the remaining portions must be devoid of any source-indicating character. This ruling reinforces a cautious approach to dissecting trademarks, aiming to ensure that similarity assessments reflect the overall commercial impression a mark makes on traders and consumers, rather than focusing unduly on shared fragments that may not be perceived independently in the marketplace.