Dismissing a Director in Japan: When is it "Justifiable" to Avoid Paying Damages?

Case: Action for Cancellation of a Shareholders' Meeting Resolution, etc.

Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of January 21, 1982

Case Number: (O) No. 974 of 1981

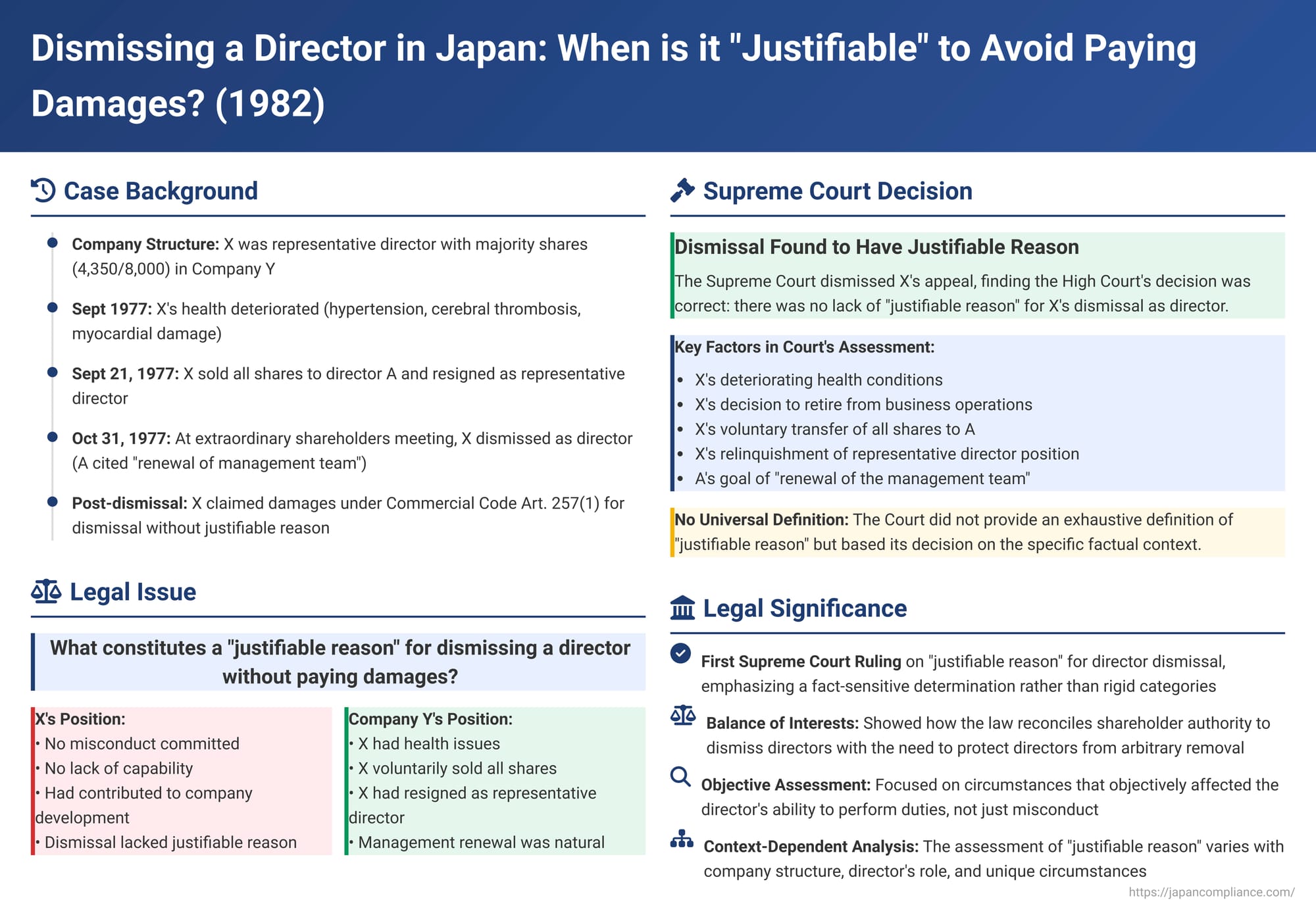

Under Japanese company law, shareholders generally have the power to dismiss a director at any time through a resolution at a shareholders' meeting (Companies Act Article 339, Paragraph 1). However, this power is not absolute when it comes to financial consequences. If a director is dismissed without a "justifiable reason" (seitō riyū), the company may be liable to pay damages to the dismissed director for losses arising from the dismissal (Companies Act Article 339, Paragraph 2). But what exactly constitutes a "justifiable reason"? A key Supreme Court decision from January 21, 1982, shed light on this crucial question, emphasizing the importance of the specific factual context.

A Change at the Helm: Facts of the Case

The dispute involved Company Y, where X was the representative director and held a majority of the shares (4,350 out of 8,000). A, another director who held 2,350 shares, and X's wife, B (who was a nominal director), were also on the board. In practice, X and A jointly managed the company.

Around September 1977, X's health significantly deteriorated due to chronic hypertension, a cerebral thrombosis, and newly developed myocardial damage. Recognizing the need to step away from the demands of the business and focus on his health, X took several decisive steps on September 21, 1977:

- He entered into an agreement to sell all his shares in Company Y to A.

- He concurrently agreed to resign from his position as representative director, with A to take over this role.

Subsequently, a board of directors' resolution was recorded, formally accepting X's resignation as representative director and appointing A as his successor. Once A assumed the role of representative director, he decided to implement a "renewal of the management team." To this end, an extraordinary shareholders' meeting was convened on October 31, 1977. At this meeting, resolutions were passed to dismiss both X and his wife, B, as directors. Two new directors were appointed to replace them. This shareholders' meeting resolution became the focal point of the legal battle.

The Legal Challenge: Dismissal With or Without Justifiable Reason?

X initially challenged the October 31, 1977 shareholders' meeting resolution on procedural grounds, seeking either a confirmation of its nullity or, alternatively, its cancellation. The court of first instance (Fukuoka District Court, judgment dated July 11, 1980) dismissed these claims.

X then appealed to the Fukuoka High Court. In this appeal, he introduced an additional claim: a demand for damages from Company Y under the then-Commercial Code Article 257, Paragraph 1, proviso (the predecessor to the current Companies Act Article 339, Paragraph 2). X argued that his dismissal as a director (distinct from his earlier voluntary resignation as representative director) lacked any "justifiable reason." He asserted that he had not committed any misconduct, nor did he lack the capacity to perform his duties as a director. On the contrary, he presented himself as a meritorious individual who had significantly contributed to Company Y's growth and development.

The High Court (judgment dated June 16, 1981), however, was not persuaded. It upheld the first instance court's decision and also dismissed X's newly added claim for damages. The High Court opined that Company Y's decision to dismiss X as a director was "quite natural for company management" under the circumstances. Aggrieved by this decision, X appealed to the Supreme Court, but solely on the issue of his claim for damages – specifically, whether a "justifiable reason" existed for his dismissal as a director.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation: No Lack of Justifiable Reason Found

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated January 21, 1982, dismissed X's appeal.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: A Confluence of Factors

The Supreme Court's reasoning was concise and heavily fact-dependent. It explicitly endorsed the factual findings of the High Court, which were:

- X, who had been the representative director of Company Y, experienced a worsening of his chronic health conditions around September 1977. Consequently, to focus on his recovery, he decided to retire from the business operations of Company Y. In line with this decision, he transferred all his shares in Company Y to director A and concurrently relinquished his position as representative director to A.

- A, having taken over as representative director and aiming for a "renewal of the management team," convened the extraordinary shareholders' meeting on October 31, 1977, at which X was dismissed as a director by resolution.

Given these established facts, the Supreme Court concluded that the High Court's judgment—which stated that it could not be said that there was an absence of "justifiable reason" under the Commercial Code for Company Y's dismissal of X as a director—was correct and could be affirmed. The Supreme Court found no legal error in the High Court's decision on this point.

Analysis and Implications: Deciphering "Justifiable Reason"

This 1982 Supreme Court decision, though brief in its direct reasoning, offers valuable insights when placed within the broader context of Japanese corporate law concerning director dismissals.

- The Purpose of Companies Act Article 339, Paragraph 2:

This provision (and its predecessor in the Commercial Code) attempts to strike a delicate balance. On one hand, Article 339, Paragraph 1 grants shareholders the fundamental freedom to dismiss directors at any time, which is a key mechanism for shareholder oversight and control, especially in widely-held public companies. On the other hand, directors, particularly those with fixed terms, have a legitimate expectation of serving their term. If directors could be dismissed at any moment without cause and without recourse, their positions would be highly unstable, potentially deterring capable individuals from serving and disrupting consistent company management. Article 339, Paragraph 2 seeks to reconcile these competing interests by allowing dismissal but mandating compensation if it's done without a "justifiable reason." The interpretation of "justifiable reason," therefore, must reflect this intended balance.

Regarding the burden of proof, the generally accepted view, consistent with this case, is that the dismissed director must prove their dismissal and the resulting damages. The company then bears the burden of proving the existence of a "justifiable reason" to avoid liability for these damages. - Nature of the Damages Liability:

The liability for damages under Article 339, Paragraph 2 is not typically conceptualized as arising from tort (unlawful act) or a breach of contract. Dismissing a director is, in itself, a lawful act permitted by statute. Instead, the prevailing legal theory views this liability as a "special statutory liability" (hōtei sekinin setsu) rooted in principles of equity and fairness, designed to compensate for the loss of the director's expected term. Damages generally include the remuneration the director would have earned during the remainder of their term, and potentially retirement allowances or bonuses if their payment was highly probable. - What Constitutes a "Justifiable Reason"?

This is the central question. Legal scholarship and lower court jurisprudence have explored various categories of potential justifiable reasons:- Misconduct or Breach: Acts of malfeasance, serious negligence, or significant violations of laws or the company's articles of incorporation by the director.

- Incapacity: Serious physical or mental illness rendering the director incapable of performing their duties.

- Lack of Competence: A demonstrable lack of skill, ability, or diligence necessary for the role, leading to poor performance.

- Breakdown of Trust: A severe loss of trust between the director and major shareholders or other board members, making continued cooperation impossible. However, this generally does not include mere personal disagreements, a preference for another candidate, or minor policy differences.

- Business Judgment Failures: Significant errors in business judgment leading to substantial harm to the company. This category is highly debated, as holding directors financially liable for bona fide business decisions that turn out poorly could stifle entrepreneurial risk-taking.

It's generally accepted that severe instances of misconduct, incapacity, or incompetence can constitute justifiable reasons.

- Interpreting This Supreme Court Decision:

This 1982 case was the Supreme Court's first ruling specifically on the meaning of "justifiable reason" in this context. A key takeaway is that "justifiable reason" is not confined to situations that would also give grounds for a shareholder to sue for a director's removal (e.g., serious misconduct under Companies Act Article 854).

The decision appears to place significant weight on:- X's deteriorating health.

- X's own voluntary actions: his decision to retire from active involvement in the business, his sale of all his shares (indicating a complete exit from ownership), and his relinquishing of the top executive post of representative director.

The Court also mentions A's intention to "renew the management team." While this is noted as part of the factual background, the judgment doesn't delve into whether X specifically lacked competence or if there were concrete business strategy disagreements that necessitated this renewal beyond A taking control. Without more detailed findings on such aspects, it is difficult to interpret this phrase as an independent, broadly applicable justifiable reason on its own. The confluence of X's health, his complete divestment, and his stepping down from day-to-day leadership seems to be the critical cluster of facts.

- Determining "Justifiable Reason": An Objective Assessment:

The existence of a "justifiable reason" is generally judged objectively: were there circumstances, existing at the time of dismissal, that genuinely hindered or would hinder the director's ability to perform their duties or that otherwise made their continuation in office detrimental to the company's legitimate interests? Some legal theories and court decisions suggest that the company's subjective awareness or articulation of these reasons at the exact moment of dismissal may not be strictly necessary if the objective grounds for dismissal did, in fact, exist.

While courts often try to categorize the reasons (e.g., into the five points listed above), there's discussion about whether a combination of several minor issues, none of which would suffice on its own, can cumulatively amount to a justifiable reason. Some recent lower court cases, like a 2018 Tokyo District Court decision, have adopted such a holistic approach, considering multiple factors together. - The Role of Specific Circumstances and Appointment Context:

An emerging consideration in Japanese case law is the extent to which the specific circumstances of a director's appointment and the mutual understandings at that time should influence the assessment of "justifiable reason" for dismissal. For instance, if a director was appointed for a specific skill set (e.g., tax expertise, as in one lower court case involving an auditor) and repeatedly failed in that area, dismissal was found justifiable. Another lower court case (concerning non-reappointment, which has parallels) considered the initial purpose of appointing a director (e.g., to provide financial support), and if that purpose had been fulfilled, a decision not to retain the director might be seen as having a justifiable basis. These cases suggest that the initial premises of the director-company relationship can be relevant. - Challenges in Modern Diverse Corporate Environments:

Given the increasing diversity in company structures (public, private, subsidiary, joint venture) and the varied roles directors are expected to play, establishing a universal, one-size-fits-all definition of "justifiable reason" is exceedingly difficult. What might be justifiable in a small, owner-managed business facing a health crisis of its key person might be different in a large, publicly traded corporation with a professionalized management team.

As legal commentary points out, if the concept is interpreted too broadly, it could make directors overly vulnerable and hesitant to take necessary risks. If interpreted too narrowly, it could excessively constrain shareholders' ability to effect necessary changes in leadership.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1982 decision in the case of X and Company Y underscores that the determination of a "justifiable reason" for dismissing a director is highly fact-sensitive. In this specific instance, X's severe health issues, coupled with his own actions of completely divesting his ownership, retiring from active business, and stepping down as representative director, were pivotal. When the new representative director, A, subsequently moved to dismiss X from his remaining (and at that point, perhaps largely formal) role as a director as part of a management overhaul, the Court found that, collectively, these circumstances did not demonstrate a lack of justifiable reason.

While the ruling doesn't provide an exhaustive definition of "justifiable reason," it serves as an important precedent. It illustrates that circumstances largely driven by the director's own health and decisions to withdraw from the company can contribute significantly to a finding that their subsequent dismissal as a director was justifiable, thereby shielding the company from a claim for damages. The case continues to be a vital reference point in the ongoing effort to balance shareholder prerogatives with the fair treatment of corporate directors.