Dismissal Without Notice in Japan: The Hosotani Clothing Case and Its Enduring Impact (March 11, 1960)

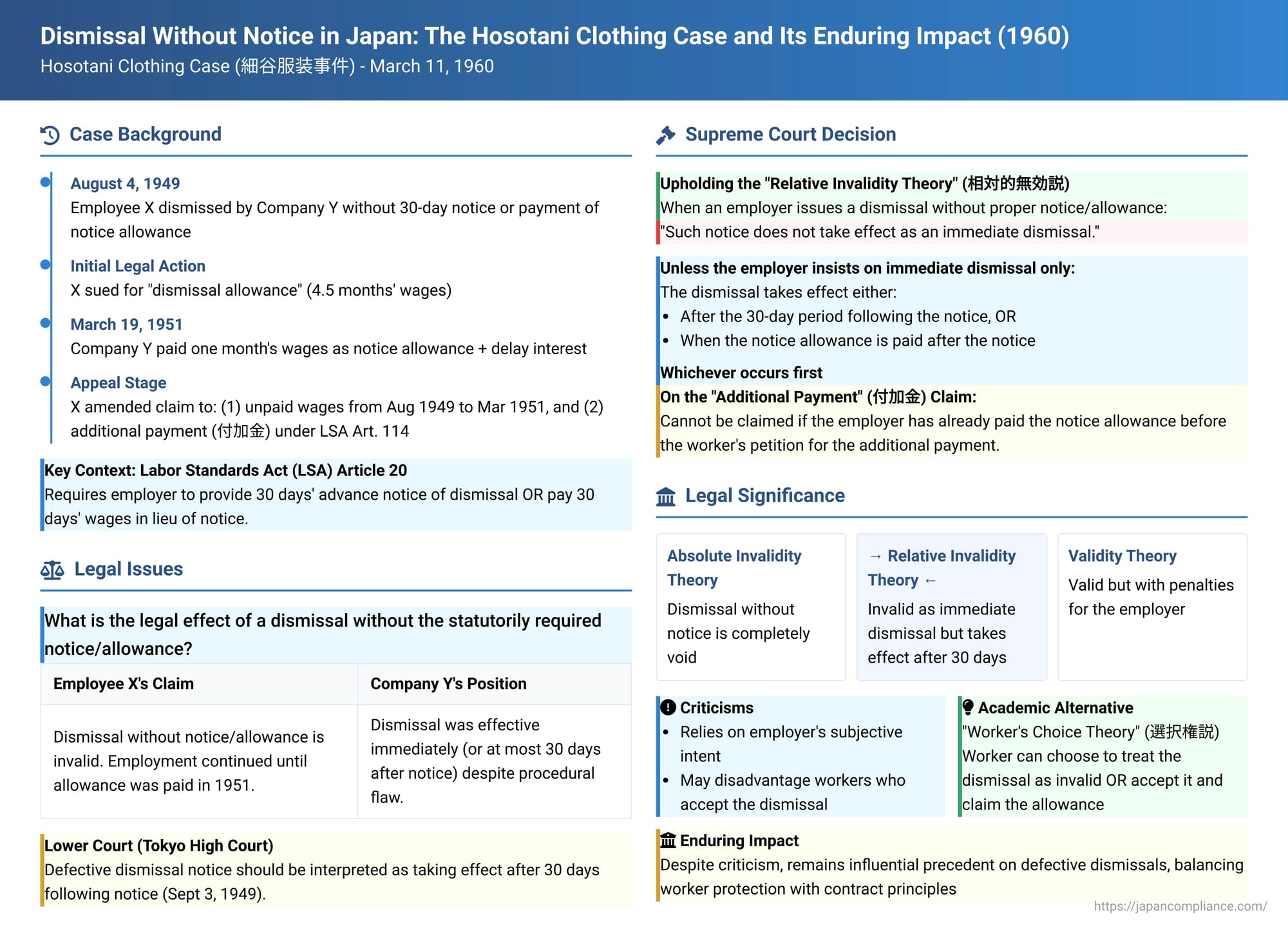

On March 11, 1960, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a judgment in a case known as the "Hosotani Clothing Case" (細谷服装事件). This ruling became a foundational precedent in Japanese labor law concerning the legal effect of an employer dismissing an employee without providing the statutorily required 30-day notice period or, alternatively, paying 30 days' wages in lieu of such notice (解雇予告手当 - kaiko yokoku teate), as mandated by Article 20 of the Labor Standards Act (LSA). The case explored whether such a procedurally flawed dismissal is immediately void or if it can take effect at a later point.

An Abrupt Dismissal and a Shifting Legal Claim

The plaintiff, X, was employed by Defendant Company Y, a business engaged in clothing manufacturing and repair, performing general administrative and bookkeeping duties. On August 4, Showa 24 (1949), Company Y unilaterally informed X of dismissal without either providing the advance notice or paying the dismissal notice allowance.

Initially, X sued Company Y, asserting that the dismissal was unjust and, based on then-prevailing practices in general companies, claimed a "dismissal allowance" equivalent to 4.5 months' wages, along with delay interest. The first instance court (Yokohama District Court) dismissed these claims.

A significant development occurred on March 19, Showa 26 (1951), the same day the first instance judgment was rendered. On this date, Company Y paid X the salary for August 1949 and, crucially, an amount equivalent to one month's wages as the dismissal notice allowance, plus accrued delay interest.

This subsequent payment by Company Y led X to amend the legal basis of the claim during the appeal process. X then argued that a dismissal made in violation of LSA Article 20 (i.e., without proper notice or pay in lieu) is legally invalid. X contended that the dismissal only became effective on March 19, 1951, the date Company Y actually paid the dismissal notice allowance. Based on this, X claimed unpaid wages for the period from August 1949 up to March 1951. Additionally, X sought an "additional payment" (付加金 - fukakin) under LSA Article 114, alleging Company Y's violation of LSA Article 20 at the time of the original dismissal notification in August 1949.

The Tokyo High Court (acting as the original trial court for the purposes of the Supreme Court appeal in this context) rendered a judgment that:

- A dismissal notice issued without either the requisite notice period or payment of the notice allowance cannot take effect as an immediate dismissal.

- However, unless the employer's intention is to insist on an immediate dismissal and they would not intend to dismiss otherwise, such a defective dismissal notice should be interpreted as taking effect after the lapse of the statutory 30-day period following the notice.

- Applying this, the High Court concluded that Company Y's dismissal notice to X on August 4, 1949, became legally effective 30 days later, meaning the employment relationship terminated at the end of September 3, 1949.

- Consequently, X's claim for unpaid wages beyond September 3, 1949, was dismissed.

X appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: The "Relative Invalidity" Theory

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's core reasoning regarding when the dismissal became effective.

On the Effect of Dismissal Without Proper Notice or Pay in Lieu

The Supreme Court laid down the following principle:

"When an employer notifies a worker of dismissal without observing the notice period prescribed in Article 20 of the Labor Standards Act or without paying the notice allowance, such notice does not take effect as an immediate dismissal.

However, unless the employer's intention is to insist on an immediate dismissal (and would not dismiss otherwise), the dismissal takes effect either after the lapse of the 30-day period prescribed in said Article following the notice, OR when the notice allowance prescribed in said Article is paid after the notice, whichever occurs first.

The High Court's judgment, which held that the dismissal notice in this case took effect upon the lapse of the 30-day period, is correct."

On the "Additional Payment" (Fukakin) Claim

Regarding X's claim for an additional payment under LSA Article 114 (which allows courts to order employers to pay an additional sum, up to the amount of unpaid wages/allowances, as a penalty for certain LSA violations, including Article 20):

- The Supreme Court stated: "The obligation for an additional payment under Article 114 of the Labor Standards Act does not arise automatically when an employer fails to pay notice allowance, etc. It arises only when a court orders such payment upon the worker's request."

- Critically, it continued: "Therefore, even if an employer violates Article 20, if the employer has already completed payment of an amount equivalent to the notice allowance and the employer's state of breach of duty has ceased, the worker cannot thereafter petition for an additional payment."

Since Company Y had paid the notice allowance (on March 19, 1951) before X specifically sought the fukakin in relation to the non-payment of the notice allowance, the Supreme Court found the High Court's judgment on this point (which presumably denied the fukakin for this reason) to be correct.

The Legal Labyrinth of Defective Dismissals: Theories and Debates

The Hosotani Clothing case was decided against a backdrop of considerable legal debate about the private law consequences of an employer's failure to comply with LSA Article 20.

- Purpose of LSA Article 20: This article modifies the general civil law principle (Civil Code Art. 627(1), which requires 2 weeks' notice for terminating indefinite term contracts) by imposing a stricter requirement on employers: at least 30 days' advance notice of dismissal or payment of 30 days' average wages in lieu of notice. The primary aim is to protect workers from the immediate financial hardship of sudden job loss. Violations can lead to penal sanctions (LSA Art. 119) and court-ordered additional payments (fukakin under LSA Art. 114). However, the LSA itself does not explicitly state whether a dismissal made in contravention of Article 20 is valid, invalid, or has some other effect on the employment contract.

- Historical Legal Theories: Prior to the Hosotani Supreme Court ruling, three main theories existed:

- Absolute Invalidity Theory (無効説 - mukōsetsu): This view, emphasizing worker protection, considered LSA Article 20 a mandatory provision, meaning any dismissal violating it was entirely void. The employment contract would continue unaffected. A significant doctrinal problem with this theory was its incompatibility with LSA Article 114; if the dismissal is void, then technically no dismissal has occurred, meaning no dismissal notice allowance is "due" for non-payment, rendering the fukakin (additional payment for failing to pay the allowance) illogical.

- Validity Theory (有効説 - yūkōsetsu): This theory regarded LSA Article 20 primarily as a regulatory provision with penal sanctions, arguing that a violation did not affect the civil law validity of the dismissal itself. The dismissal would be effective according to its terms, but the employer would be liable for the notice allowance and potentially a fukakin, thus resolving the LSA Art. 114 contradiction. However, this view was criticized for potentially weakening worker protection.

- Relative Invalidity Theory (相対的無効説 - sōtaiteki mukōsetsu): This intermediate theory proposed that a dismissal issued without proper notice or pay in lieu was invalid as an immediate dismissal. However, if the employer did not insist on the dismissal being immediate (and would still want to dismiss even if not immediate), the dismissal would take effect once the LSA Article 20 requirements were subsequently met – either after 30 days had passed from the defective notice, or upon the employer later paying the dismissal notice allowance. This was also the prevailing administrative interpretation at the time.

- The Supreme Court's Adoption of Relative Invalidity: The Hosotani judgment established the Relative Invalidity Theory as the Supreme Court's official stance, although it did not provide extensive reasoning for this choice.

- Criticisms and Challenges of the Relative Invalidity Theory: The commentary notes that this theory has faced significant academic criticism and is not widely supported by scholars today. Key criticisms include:

- Employer's Subjective Intent: Determining whether an employer "insists on immediate dismissal" delves into the employer's subjective intentions, which can be difficult to ascertain and may lead to the validity of the dismissal being dependent on the employer's subsequent actions or assertions. There's also a theoretical difficulty in explaining how a legally invalid act (the initially defective dismissal) can be "converted" into a valid one later.

- Potential Disadvantage to Workers: If a worker, faced with a defective dismissal, accepts it and stops offering their labor, the subsequent passage of 30 days could validate the dismissal under this theory. This might then preclude the worker from claiming the dismissal notice allowance (as the dismissal eventually became "valid" with notice) or the fukakin. Furthermore, their claim for wages during this 30-day "curing" period could be denied if they are deemed to have had no intention to work.

- Post-Hosotani Judicial and Academic Developments:

- Lower Court Applications: While many lower courts followed the Supreme Court's relative invalidity approach, some attempted to mitigate its potential harshness. For example, some courts awarded wages for the 30-day period if the employer had refused the worker's labor after the defective notice, or allowed a claim for the notice allowance even if the worker had ceased offering labor. Cases where employers were deemed to be rigidly insisting on an immediate, unlawful dismissal sometimes saw courts refusing to allow the "conversion" to a valid dismissal after 30 days.

- The "Worker's Choice Theory" (選択権説 - sentakuken setsu): This theory, which gained traction among academics after the Hosotani ruling and is now a majority scholarly view, proposes that when an employer violates LSA Article 20, the affected employee has a choice:

- They can treat the dismissal as entirely invalid (in which case the employment relationship continues, and no claim for dismissal notice allowance arises).

- Alternatively, they can accept the termination of employment as effective (perhaps as of the defective notice date or after a period) and then claim the dismissal notice allowance, plus the fukakin under LSA Article 114 for the Article 20 violation. This approach is seen as resolving the internal contradiction with LSA Article 114 more cleanly. Some early lower court decisions adopted this worker's choice perspective.

- Resurgence of the "Validity Theory": The commentary also notes that some contemporary legal scholars have argued for a return to the "Validity Theory". Their reasoning includes that LSA Article 20's primary aim is to cushion the economic blow of dismissal and that its text doesn't explicitly link compliance to the dismissal's private law validity. Furthermore, with the robust development of the "abuse of dismissal right" doctrine in Japanese law (now codified in Article 16 of the Labor Contract Act), which provides substantive protection against unfair dismissals, the need to tie the procedural requirement of LSA Article 20 directly to the dismissal's validity is arguably diminished.

Conclusion: A Contentious but Enduring Precedent

The Supreme Court's 1960 judgment in the Clothing Company H (Hosotani Clothing) case established the "Relative Invalidity Theory" as the prevailing judicial interpretation for dismissals failing to meet the notice requirements of LSA Article 20. According to this theory, such dismissals are not outright void but can become effective either after 30 days from the defective notice or upon subsequent payment of the notice allowance, unless the employer was unyieldingly fixated on an immediate dismissal. The ruling also clarified that the "additional payment" (fukakin) for LSA violations is not an automatic entitlement and cannot be claimed if the employer rectifies the underlying payment default before a court order.

While the Hosotani decision provided a framework, its reliance on assessing the employer's subjective intent and its potential implications for workers' subsequent claims have led to persistent academic criticism and the development of alternative theories, notably the "Worker's Choice Theory." Nevertheless, the Hosotani ruling remains a significant, though debated, precedent in the complex area of dismissal law in Japan, highlighting the ongoing efforts to balance statutory worker protections with principles of contract law.