Dismissal During Work-Related Injury Leave: Japan's Supreme Court Clarifies Termination Compensation Exception (June 8, 2015)

Japan’s Supreme Court ruled that employers may invoke the Labour Standards Act termination‑compensation exception to dismiss workers on prolonged injury leave, even when WCAI benefits, not company payments, are being received.

TL;DR

- Japan’s Supreme Court (June 8 2015) held that paying Article 81 “termination compensation” lifts the Article 19 dismissal ban even when the worker is receiving Workers’ Accident Compensation Insurance (WCAI) benefits.

- WCAI benefits are deemed a substitute for the employer’s own LSA Chapter 8 obligations; substance prevails over payment source.

- Employers may still be liable under Labour Contract Act Art. 16 if dismissal lacks objective reasonableness or social acceptability.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: Long‑Term Absence, Workers’ Comp, and Dismissal

- Legal Framework: Dismissal Restriction and Termination Compensation

- Lower Court Ruling: Strict Textual Interpretation Prevents Dismissal

- The Supreme Court’s Analysis (June 8 2015)

- Remand for Assessment of Dismissal Reasonableness

- Implications and Significance

- Conclusion

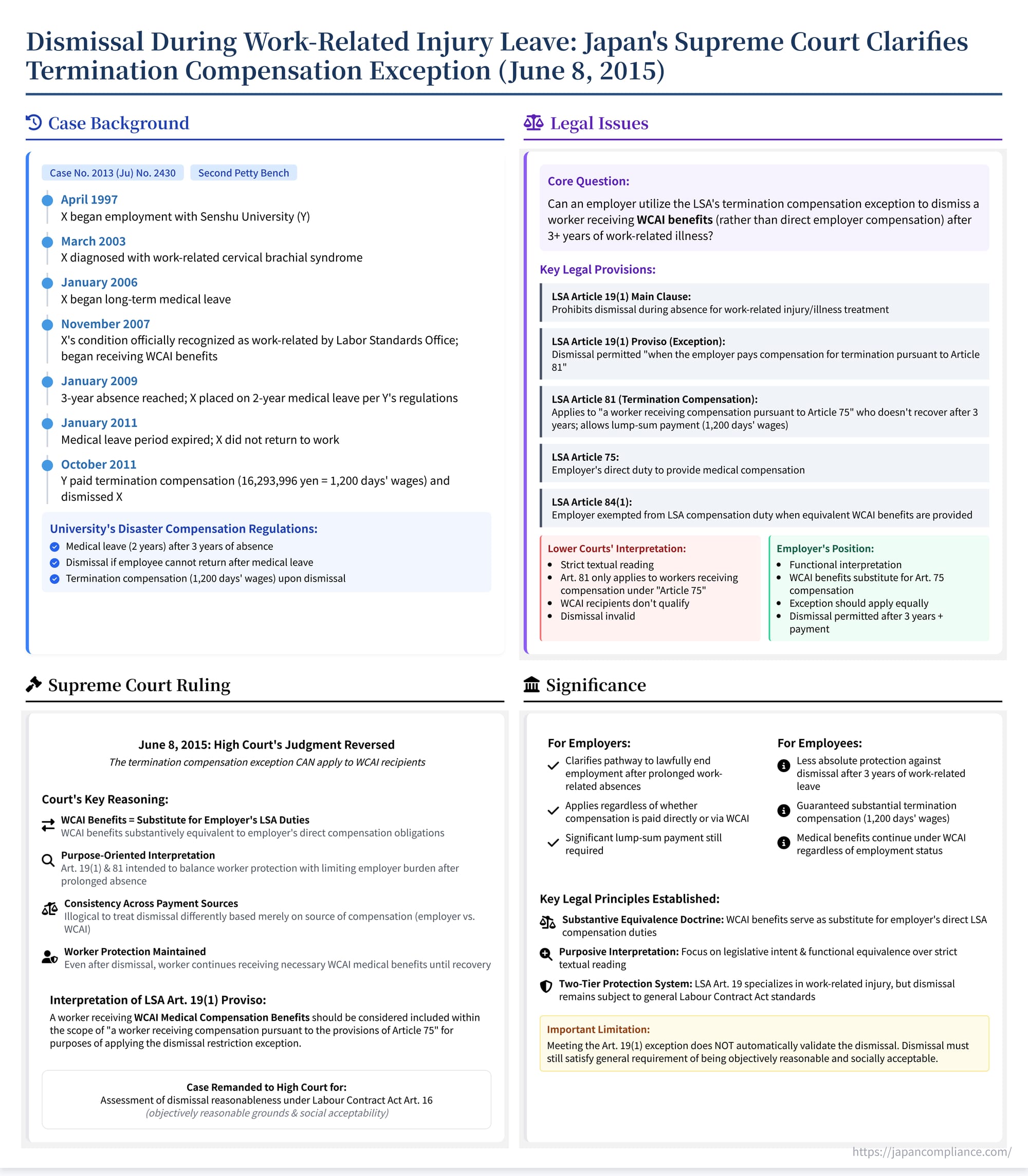

On June 8, 2015, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan issued a significant judgment addressing the relationship between Japan's Labour Standards Act (LSA) and the Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act (WCAI Act) concerning dismissal restrictions for employees on leave due to work-related injuries or illnesses (Case No. 2013 (Ju) No. 2430, "Confirmation of Status etc. Counterclaim Case"). The case centered on whether an employer could utilize the LSA's "termination compensation" (uchikiri hoshō) provision to dismiss an employee after three years of medical leave, even when the employee was receiving benefits under the WCAI Act rather than directly from the employer under the LSA's compensation provisions. The Court ruled that the termination compensation exception can apply in such cases, effectively holding that WCAI benefits function as a substitute for the employer's direct LSA compensation duties for the purpose of this dismissal rule. This decision provides crucial clarification on navigating long-term absences and dismissals related to workplace injuries in Japan.

Factual Background: Long-Term Absence, Workers' Comp, and Dismissal

The case involved a long-serving employee of a private university and the application of internal regulations and national labor laws:

- Employment and Illness: The appellee, X, began working for the appellant, Y (University, a school corporation), in April 1997. Around March 2002, X started experiencing symptoms like shoulder stiffness. In March 2003, X was diagnosed with cervical brachial syndrome (頸肩腕症候群 - keikenwan shōkōgun).

- Work-Related Injury Recognition & Leave: Following repeated absences, X commenced a long-term absence from work starting January 17, 2006. In November 2007, the Central Labour Standards Inspection Office Director officially recognized X's condition (as of March 20, 2003) as a work-related illness (gyōmujō no shippei). Consequently, X began receiving Medical Compensation Benefits (療養補償給付 - ryōyō hoshō kyūfu) and Temporary Disability Compensation Benefits (休業補償給付 - kyūgyō hoshō kyūfu) under the WCAI Act.

- Employer's Internal Regulations: Y (the university) had internal Disaster Compensation Regulations (honken kitei) outlining procedures for work-related injuries/illnesses, including provisions beyond the statutory WCAI benefits ("non-statutory compensation" - 法定外補償 hōteigai hoshō). These regulations included:

- Medical Leave: If a full-time employee is absent due to a work-related disaster for 3 years and still cannot work, they are placed on medical leave for a specified period based on years of service (Rule 13). For X (10-20 years of service), this period was 2 years (Rule 13(2)).

- Dismissal upon Leave Expiration: If the reason for leave persists after the leave period expires, the employee shall be dismissed (kaishoku) (Rule 14(3)).

- Termination Compensation: If an employee receiving WCAI benefits (and non-statutory compensation from Y) is dismissed under Rule 14(3), LSA Article 81 applies, and the employer shall pay termination compensation (uchikiri hoshōkin) equivalent to 1200 days of average wages (Rule 9).

- Application of Regulations and Dismissal:

- On January 17, 2009, X's absence due to the work-related illness reached 3 years. As X remained unable to work, Y placed X on a 2-year medical leave according to Rule 13(2).

- The 2-year leave period expired on January 17, 2011. X did not comply with Y's request to return to work, instead demanding return-to-work training.

- Y concluded that X was clearly unable to return to work. On October 24, 2011, Y paid X termination compensation amounting to 16,293,996 yen (calculated as 1200 days of average wages per Rule 9).

- Subsequently, Y issued a notice dismissing X effective October 31, 2011 ("the Dismissal").

- (Note: Y had also separately paid X non-statutory compensation totaling approx. 19 million yen between 2009 and 2012 under its regulations).

Legal Framework: Dismissal Restriction and Termination Compensation

X challenged the dismissal's validity, primarily based on the dismissal restriction stipulated in the Labour Standards Act (LSA):

- LSA Article 19, Paragraph 1 (Main Clause): Prohibits an employer from dismissing a worker during a period of absence for medical treatment due to a work-related injury or illness, and for 30 days thereafter. This provides strong protection against dismissal while recovering from work-related conditions.

- LSA Article 19, Paragraph 1 (Proviso): Creates an exception to this dismissal restriction. The restriction does not apply "when the employer pays compensation for termination pursuant to Article 81."

- LSA Article 81 (Termination Compensation): Allows an employer to discontinue ongoing compensation obligations under the LSA by paying a lump sum equivalent to 1200 days of average wages, specifically if "a worker receiving compensation pursuant to the provisions of Article 75" has not recovered from the work-related injury or illness after 3 years from the start of medical treatment.

- LSA Article 75 (Medical Compensation): Defines the employer's direct duty under the LSA to provide necessary medical compensation to a worker injured or taken ill due to work.

- LSA Article 84, Paragraph 1 (Exemption Due to WCAI): States that if benefits equivalent to the LSA's disaster compensation duties are provided under the WCAI Act, the employer is exempted from their direct LSA compensation duty to the extent of those benefits.

- WCAI Act: Establishes the mandatory workers' compensation insurance system, funded primarily by employer premiums, which provides benefits (like medical compensation and temporary disability compensation) for work-related injuries and illnesses, largely substituting for the employer's direct LSA obligations.

The Core Legal Question: The crux of the case was the interpretation of the link between LSA Art. 19(1) proviso and Art. 81. The proviso allows dismissal if termination compensation is paid under Art. 81. Article 81, in turn, explicitly refers to workers receiving compensation under Art. 75 (the employer's direct duty). Since X was receiving benefits under the WCAI Act (which exempts the employer from the Art. 75 duty per Art. 84), did X technically fall outside the scope of workers described in Art. 81? If so, could the employer Y invoke the Art. 19(1) proviso to justify the dismissal?

Lower Court Ruling: Strict Textual Interpretation Prevents Dismissal

The High Court (Tokyo High Court), affirming the first instance court, adopted a strict textual interpretation. It reasoned:

- LSA Article 81 explicitly applies to workers receiving compensation under "Article 75."

- X was receiving benefits under the WCAI Act, not directly from the employer under LSA Article 75.

- Therefore, X was not a worker covered by Article 81.

- Consequently, the condition for the dismissal restriction exception in Article 19(1) proviso (payment of termination compensation pursuant to Article 81) was not met.

- As a result, the dismissal of X during a period protected by Article 19(1) main clause (leave for work-related illness) was invalid.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (June 8, 2015)

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated June 8, 2015, disagreed with the lower courts' strict textual interpretation and held that the termination compensation exception could apply even when the employee receives WCAI benefits. The Court overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case.

1. Substantive Relationship Between LSA Compensation and WCAI Benefits:

The Court began by analyzing the fundamental relationship between the employer's direct compensation duties under LSA Chapter 8 and the benefits provided under the WCAI Act.

- It reviewed the legislative history and the interlocking provisions (LSA Art. 84(1), WCAI Act Art. 12-8(2)), concluding that the WCAI system was established precisely as a mechanism to ensure workers receive necessary compensation while alleviating the direct financial burden on employers imposed by the LSA.

- The Court reaffirmed its long-standing position (citing a Showa 52 [1977] precedent) that WCAI benefits are substantively equivalent to, and serve as a substitute for, the employer's direct disaster compensation obligations under the LSA. In essence, when WCAI benefits are paid, it is the government fulfilling, through an insurance mechanism, the duty that the LSA originally placed on the employer.

2. Purpose of the Termination Compensation and Dismissal Exception:

The Court considered the dual purpose of LSA Art. 81 and its connection to Art. 19(1) proviso:

- Ending Compensation Duty: Article 81 allows the employer, after 3 years of providing (or being liable for) medical compensation under Art. 75 without the worker recovering, to make a substantial lump-sum payment (1200 days' wages) and thereby terminate their future compensation obligations under the LSA.

- Ending Employment Relationship: The proviso in Art. 19(1) links directly to this Art. 81 payment, allowing the employer, upon making this payment under the same conditions (3 years of medical leave without recovery), to also overcome the dismissal restriction and terminate the employment relationship itself. This relieves the employer from the burden of maintaining employment indefinitely during a worker's prolonged inability to work due to a work-related condition.

3. Consistency Requires Including WCAI Recipients:

Given that WCAI benefits are a substitute for the employer's LSA compensation duties, the Court reasoned it would be inconsistent to treat the application of the Art. 19(1) dismissal exception differently based merely on the source of the compensation payments (employer directly vs. government via WCAI).

- The underlying situation triggering the exception – a worker unable to work for over 3 years despite ongoing medical compensation for a work-related condition – is the same.

- The employer's burden associated with the prolonged absence (maintaining the employment relationship, potential administrative costs, etc.) exists regardless of whether WCAI is paying the benefits.

- The rationale for allowing dismissal after 3 years plus a significant lump-sum payment (balancing worker protection with employer burden) applies equally in both scenarios.

4. Worker Protection Considerations:

The Court also considered worker protection. It noted that even if an employer dismisses a worker after paying termination compensation under this interpretation, the worker receiving WCAI benefits continues to receive necessary Medical Compensation Benefits (ryōyō hoshō kyūfu) under the WCAI Act until their injury or illness is cured (or symptoms stabilize). This ongoing medical coverage mitigates potential harm to the worker resulting from the dismissal. Therefore, allowing the dismissal exception to apply to WCAI recipients does not necessarily leave the worker without essential protection regarding their medical needs.

5. Interpretive Conclusion on LSA Art. 19(1) Proviso:

Based on the substitutive nature of WCAI benefits, the purpose of the termination compensation and dismissal exception rules, and considerations of consistency and worker protection, the Court concluded:

- A worker receiving WCAI Medical Compensation Benefits (under WCAI Act Art. 12-8(1)(i)) should be considered included within the scope of "a worker receiving compensation pursuant to the provisions of Article 75" as referred to in LSA Article 81, specifically when applying the dismissal restriction exception under LSA Article 19, Paragraph 1, proviso.

6. Application to the Case:

Applying this interpretation to the facts:

- X was receiving WCAI Medical Compensation Benefits.

- X's medical leave (療養 - ryōyō) had continued for more than 3 years after commencement without the illness being cured.

- Y (the employer) paid X termination compensation equivalent to 1200 days of average wages.

- Therefore, the conditions triggering the exception under LSA Art. 19(1) proviso were met.

- Consequently, the general dismissal restriction in LSA Art. 19(1) main clause did not apply to X's situation.

- The Dismissal was not automatically invalid for violating LSA Art. 19(1).

Remand for Assessment of Dismissal Reasonableness

The Supreme Court's finding only addressed the specific prohibition under LSA Art. 19. It did not rule on the ultimate validity of the dismissal itself. A dismissal, even if not violating Art. 19, must still comply with general principles of Japanese employment law, particularly Article 16 of the Labour Contract Act, which prohibits dismissals lacking objectively reasonable grounds and social acceptability (often referred to as the doctrine of abusive dismissal).

Since the High Court had found the dismissal invalid solely based on its (incorrect) interpretation of LSA Art. 19, it had not assessed whether the dismissal satisfied the requirements of Labour Contract Act Art. 16. Therefore, the Supreme Court remanded the case back to the Tokyo High Court to conduct this further examination – specifically, to determine if dismissing X after the extended leave and payment of termination compensation was objectively reasonable and socially acceptable under all the circumstances.

Implications and Significance

This 2015 Supreme Court decision significantly clarifies the application of dismissal restrictions in cases of long-term work-related injury or illness in Japan:

- WCAI Benefits = LSA Compensation for Dismissal Restriction: It establishes that, for the specific purpose of the LSA Art. 19(1) dismissal restriction exception, receiving WCAI benefits is treated as equivalent to receiving direct employer compensation under LSA Art. 75.

- Termination Compensation Exception Broadened: This effectively broadens the applicability of the LSA Art. 81 termination compensation route as a way to end employment after 3 years of work-related medical leave, making it available to employers regardless of whether compensation is paid directly or via WCAI.

- Focus on Substantive Equivalence: The ruling emphasizes the substantive equivalence between the employer's LSA duties and the WCAI benefits that replace them, prioritizing this functional relationship over a strict literal reading of the cross-referenced article numbers.

- Dismissal Still Subject to Reasonableness Test: Crucially, the decision does not grant employers an automatic right to dismiss after paying termination compensation. The dismissal must still independently satisfy the requirements of objective reasonableness and social acceptability under Labour Contract Act Art. 16. The remand highlights that factors surrounding the employee's condition, prospects for recovery/return, the employer's efforts (or lack thereof) regarding accommodation or rehabilitation, and the appropriateness of dismissal as a final measure must still be considered.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's June 8, 2015 judgment resolved a significant ambiguity regarding the interplay between the Labour Standards Act's dismissal restrictions and the Workers' Accident Compensation Insurance Act. By holding that receiving WCAI medical benefits qualifies an employee for the termination compensation exception under LSA Articles 81 and 19(1) proviso (provided the 3-year and payment conditions are met), the Court aligned the rules irrespective of the direct source of compensation. While this potentially facilitates dismissals after very prolonged work-related absences, the ruling simultaneously reaffirmed that such dismissals remain subject to scrutiny for objective reasonableness and social acceptability under general employment law principles. The decision underscores the substitutive relationship between direct employer compensation duties and the WCAI system in Japanese labor law.

- Workers’ Comp vs. Consolation Money: Japan’s Supreme Court Separates Financial and Non‑Financial Damages (1966)

- Understanding “Working Hours”: A Deep Dive into a Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on On‑Call Napping Time (2002)

- Navigating Japan’s Unique “Worker” Definition: Implications for Your US Business

- Workers’ Accident Compensation Insurance – Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

- Labour Standards Act (English Translation) – Ministry of Justice