Disguised Contracts, Implied Employment, and Retaliation: The "Pasko" Supreme Court Judgment

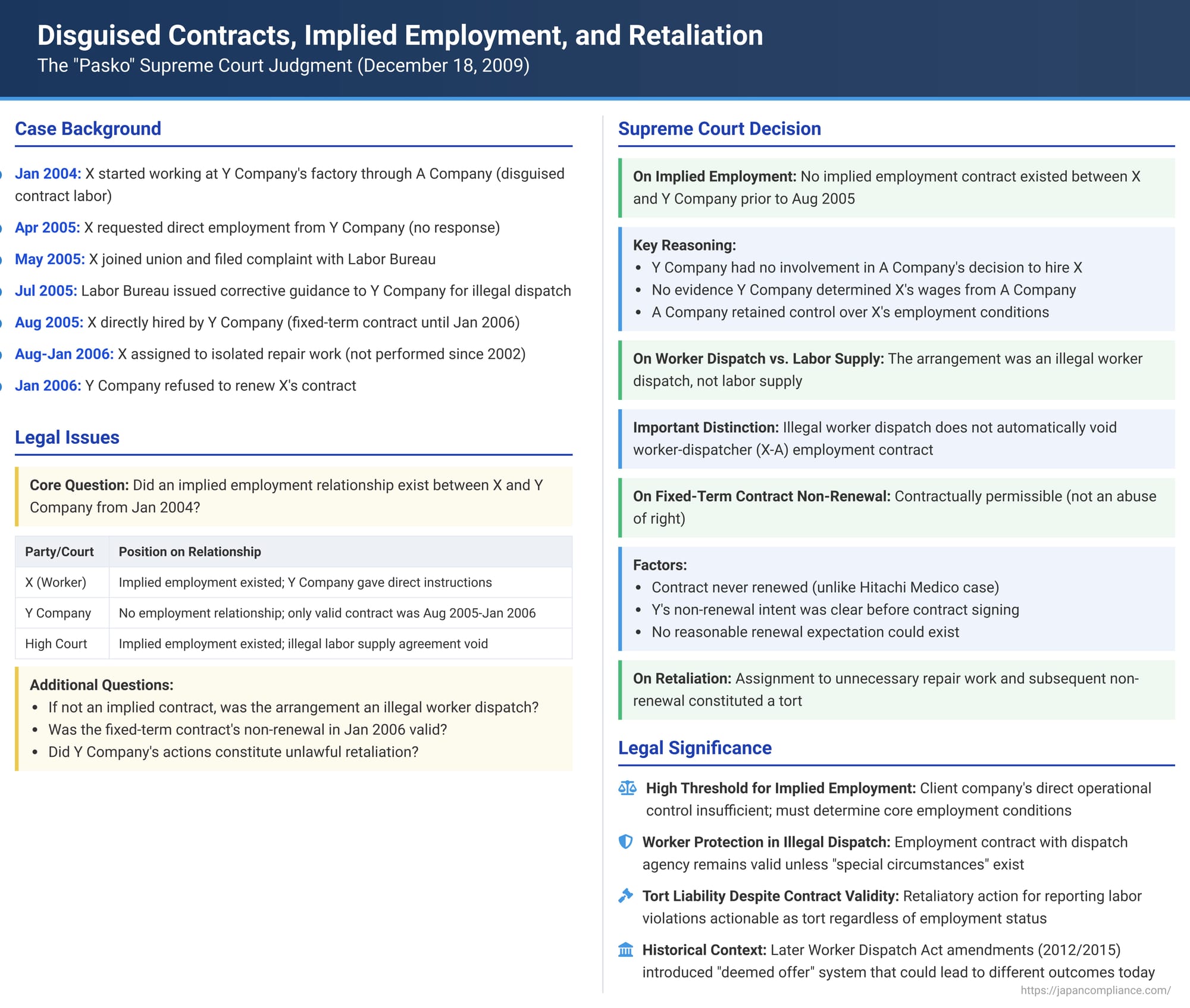

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of December 18, 2009 (Case No. 2008 (Ju) No. 1240: Claim for Confirmation of Status, etc.)

Appellant: Y Company (a plasma display panel manufacturer)

Appellee: X (Worker)

The complexities of non-typical employment arrangements, particularly those involving "disguised contract labor" (gisō ukeoi), have been a recurring theme in Japanese labor law. The Supreme Court's decision on December 18, 2009, in what is commonly known as the Panasonic Plasma Display (Pasko) case, offers significant insights into how the judiciary assesses claims of implied employment contracts with a client company, the validity of contracts in illegal dispatch scenarios, and liability for retaliatory actions.

The Tangled Web: Factual Background

The case revolved around X, a worker who initially worked at the B factory of Y Company, a manufacturer of plasma display panels (PDPs).

Initial Arrangement (January 2004 – July 2005): A Picture of Disguised Contract Labor

X's journey began on January 20, 2004, when he signed an employment contract with A Company (referred to as C in the judgment text). A Company had a business consignment agreement with Y Company to perform manufacturing tasks. X's contract with A Company was for a two-month term (renewable), and his designated place of work was Y Company's B factory. From that day, X was engaged in the sealing process within the device department at the B factory. Crucially, X received direct instructions and orders for his work from Y Company's employees, not from A Company personnel, despite A Company being his formal employer. The foremen and team leaders in X's process were all Y Company employees, and X, along with employees of Y and another company, worked together under Y's direction. X also received instructions for holiday work and break times directly from Y's employees, though sometimes holiday work instructions came from A Company's permanent staff stationed at the factory.

This setup, where a worker is formally employed by an outsourcing company but works under the direct command and control of the client company, is characteristic of "disguised contract labor." At the time X commenced work in January 2004, the dispatch of workers to manufacturing operations was, in principle, prohibited under the Worker Dispatch Act (it was liberalized from March 1, 2004).

X's Challenge and Y Company's Response (April 2005 – July 2005)

Believing his employment situation to be in violation of labor laws, specifically the Worker Dispatch Act, X took action:

- On April 27, 2005, X requested direct employment from Y Company. He received no response.

- On May 11, 2005, X joined U Union and sought collective bargaining.

- On May 26, 2005, X filed a complaint with the Labor Bureau, alleging that Y Company's practices at the B factory constituted illegal labor dispatch and violated Article 44 of the Employment Security Act (which broadly prohibits labor supply businesses not permitted under the Worker Dispatch Act).

Following an investigation, the Labor Bureau, on July 4, 2005, issued corrective guidance to Y Company. The Bureau found that the business consignment contract with A Company was, in fact, a worker dispatch arrangement and identified violations of the Worker Dispatch Act. Y Company was instructed to rectify the situation by switching to proper worker dispatch contracts.

In response, Y Company formulated an improvement plan. This involved A Company withdrawing its personnel from the device department. Y Company then entered into worker dispatch agreements with other companies to continue its PDP manufacturing operations with dispatched workers. X was offered a transfer by A Company to a different department within the B factory. However, X desired to continue working in the device department under Y Company's direct employment and thus resigned from A Company on July 20, 2005.

The Direct Contract with Y Company (August 2005 – January 2006)

After X's resignation from A Company, and following negotiations involving U Union, Y Company issued X a labor conditions notice on August 2, 2005. This notice proposed a direct employment contract with Y Company with the following terms:

- Contract Period: August 2005 to January 31, 2006. The notice stated "no renewal," although a renewal up to March 31, 2006, was mentioned as a possibility.

- Work Content: "PDP panel manufacturing – repair work and preparatory tasks, etc."

The reason Y Company offered a limited term was its intention to transition its production system to a lawful subcontracting arrangement by March 2006, a fact known to U Union.

X, facing a loss of income after leaving A Company, signed an employment contract (the "present employment contract") based on these terms on August 19, 2005, after his legal counsel sent a letter to Y Company stating X was taking the job but reserved his objections concerning the contract period and the nature of the work. The wage was set at ¥1600 per hour.

From August 23, 2005, X commenced work under this direct contract with Y Company. He was assigned to perform repair work on defective PDPs, a task he handled alone. Notably, Y Company had reportedly ceased performing such repair work around March 2002, usually discarding defective panels. X’s workspace for this repair task was enclosed by anti-static sheets.

U Union continued to demand that Y Company provide X with an indefinite-term contract and reinstate him to his former duties in the sealing process. However, on December 28, 2005, Y Company informed X that his employment contract would terminate upon its expiration on January 31, 2006. Y Company subsequently refused X's employment from February 1, 2006. The repair work X had been doing was completed by other employees over five days in February 2006, and Y Company did not conduct such work thereafter.

X then filed a lawsuit against Y Company, seeking, among other things, confirmation of an indefinite-term employment relationship.

The Lower Courts' Path

The District Court (Osaka District Court, April 26, 2007) found that Y Company's assignment of X to the repair work constituted a tort and awarded damages for this but dismissed X's other claims, including the confirmation of an employment contract with no fixed term. Both X and Y Company appealed.

The High Court (Osaka High Court, April 25, 2008) substantially overturned the District Court's decision, ruling largely in X's favor. The High Court found that an "implied employment contract" had existed between X and Y Company from the beginning of X's work at the factory (January 2004). It reasoned that the arrangement between Y Company and A Company was an illegal labor supply contract, void for violating public order (Employment Security Act Article 44). The High Court also found that Y Company had effectively determined the wages X received from A Company. Consequently, the High Court viewed the subsequent formal fixed-term contract between X and Y Company (from August 2005) as a continuation of this underlying employment relationship. The non-renewal of this contract was deemed an abuse of the right to dismiss and therefore invalid. Y Company appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Analysis and Rulings

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of December 18, 2009, partially overturned the High Court's decision. It agreed with the High Court on the tort claim but disagreed on the existence of an implied contract and the invalidity of the non-renewal.

1. Characterizing the Initial Y-A-X Arrangement (January 2004 – July 20, 2005):

The Supreme Court first dissected the legal nature of the relationship between Y Company, A Company, and X.

- Not a True "Contract for Work" (Ukeoi): The Court stated that in a genuine contract for work, the contractor (A Company) is responsible for completing the work and has sole authority to issue specific work instructions to its employees. If, however, the client (Y Company) directly issues concrete commands to the contractor's workers within its premises, the arrangement cannot be classified as a contract for work, even if that is the formal label.

- Illegal "Worker Dispatch," Not "Labor Supply": When such direct command exists and there is no direct employment contract between the client (Y Company) and the worker (X), the three-party relationship falls under the definition of "worker dispatch" as per Article 2, item 1 of the Worker Dispatch Act. The Court clarified that even if this worker dispatch is illegal (e.g., conducted without a license or into prohibited areas), it does not thereby become "labor supply" under Article 4, paragraph 6 (now paragraph 7) of the Employment Security Act, as the Worker Dispatch Act specifically carves out legitimate worker dispatch from the general prohibition on labor supply.

Thus, X was deemed to be a dispatched worker from A Company to Y Company during this period. Since Y Company did not demonstrate that this dispatch was lawful, it was in violation of the Worker Dispatch Act. - Validity of the X-A Company Employment Contract: A critical point made by the Court was that the illegality of the dispatch arrangement does not automatically render the employment contract between the dispatched worker (X) and the dispatching agency (A Company) void. This is because the Worker Dispatch Act is primarily regulatory. Invalidating the worker-dispatcher contract outright could harm the worker. The Act's purpose, including worker protection, is better served by upholding the contract and thus the dispatch agency's responsibilities as an employer, unless "special circumstances" exist. No such special circumstances were found in X's contract with A Company, meaning it remained valid.

2. Rejection of an "Implied Employment Contract" between Y Company and X (Initial Period):

The Supreme Court then addressed whether an implied employment contract existed directly between Y Company and X prior to August 2005. It concluded that such a contract could not be recognized. The key factors for this determination were:

- Y Company was not involved in A Company's decision to hire X.

- There was no evidence that Y Company effectively determined the amount of wages or other payments X received from A Company. (This contradicted the High Court's finding).

- A Company, as X's formal employer, retained some degree of control over X's specific employment conditions, such as by offering him a transfer to another department.

Based on these elements and a comprehensive review of other circumstances, the Court found insufficient grounds to infer a mutual intent to form an employment relationship directly between Y Company and X during this period.

3. The Subsequent Direct Fixed-Term Contract (Y Company and X – from August 2005):

The Court found that the direct employment contract between Y Company and X was established only from August 19, 2005, when the formal contract document was executed.

This contract clearly stipulated a fixed term ending on January 31, 2006. The Supreme Court examined whether the principles governing abusive non-renewal of fixed-term contracts (as established in earlier landmark cases like the Toshiba Yanagimachi case and the Hitachi Medico case) applied. These principles can restrict an employer's ability to refuse renewal if:

a) The fixed-term contract has, through repeated renewals, become substantially equivalent to an indefinite-term contract.

b) The worker has a reasonable expectation that the contract will be renewed.

The Court found that neither condition was met:

- The direct employment contract between Y Company and X had never been renewed.

- Y Company's intention not to renew the contract beyond the stipulated (or slightly extended) period was objectively clear to both X and U Union even before the contract was signed.

Therefore, X could not have a reasonable expectation of renewal. As such, Y Company's decision to let the contract expire on January 31, 2006, was legally permissible from a contractual standpoint.

4. Y Company's Unlawful Acts (Tort Liability):

Despite finding no ongoing employment relationship beyond January 2006, the Supreme Court upheld (in conclusion) the High Court's finding that Y Company had committed tortious acts against X.

- The assignment of X to the repair work—a task Y Company had not performed for years and which was seemingly unnecessary—was reasonably inferred to be a retaliatory measure for X having reported Y Company's illegal dispatch practices to the Labor Bureau.

- Furthermore, the eventual non-renewal (or yatoidome), when viewed as part of the entire sequence of events following X's report, was also considered to be retaliatory and constituted disadvantageous treatment.

A supplementary opinion from one of the justices reinforced this view on tort liability. It highlighted that Y Company's direct employment of X was itself a consequence of the Labor Bureau's corrective guidance. Assigning X to an unnecessary and isolating repair task, knowing X was financially vulnerable after resigning from A Company due to the illegal dispatch situation, was a retaliatory act. This conduct was seen as contrary to the spirit of Article 49-3 of the Worker Dispatch Act (which prohibits disadvantageous treatment of a dispatched worker for reporting violations). The subsequent non-renewal was viewed as a continuation of this retaliatory conduct.

Key Takeaways and Implications

The Pasko judgment offers several important lessons:

- High Threshold for Implied Employment Contracts with Client Companies: This decision reaffirms a generally strict approach by the Supreme Court regarding the establishment of an implied employment contract directly with the client company in disguised contract labor or illegal dispatch situations. The Court prioritizes the formal contractual arrangements and requires strong evidence of the client company's decisive control over fundamental employment conditions (like hiring and wages paid by the intermediary) to infer such a contract. De facto operational control by the client over the worker's tasks is not, by itself, sufficient if the intermediary retains core employer functions.

- Illegal Dispatch Does Not Automatically Void Worker-Dispatcher Contract: The ruling clarifies an important protective measure: the illegality of a dispatch operation (e.g., violations of the Worker Dispatch Act by the client or dispatcher) does not automatically nullify the employment contract between the worker and the dispatching agency, absent "special circumstances." This ensures the worker retains an employment relationship and the dispatcher remains bound by its employer obligations.

- Distinction Between Contractual Validity and Tortious Conduct: The case vividly illustrates that even if a client company is found not to have an implied employment relationship with a worker, and even if its non-renewal of a subsequent, formal fixed-term contract is contractually permissible, the client can still be held liable for tortious acts. Retaliatory measures, such as punitive work assignments or dismissals linked to a worker's lawful whistleblowing, can give rise to damages claims irrespective of the contractual analysis.

- Context of Subsequent Legal Reforms: It is important to note that this 2009 judgment predates significant amendments to the Worker Dispatch Act, particularly the 2012 revisions that introduced a "direct employment offer obligation/deemed offer system." Under this system (further amended in 2015), if a client company receives dispatched workers in violation of certain provisions of the Act (e.g., for longer than permissible periods, or in disguised contract labor), it may be deemed to have offered direct employment to the dispatched worker. Such legislative changes could lead to different outcomes regarding the establishment of a direct employment relationship in fact patterns similar to Pasko arising today.

- Judicial Approach: The Pasko decision underscores a judicial tendency to separate the analysis of contractual relationships (often interpreted strictly based on formal agreements and demonstrable intent) from the condemnation of illegal or unfair practices, which may be addressed through tort law or administrative sanctions rather than by recharacterizing the contractual structure itself.

Conclusion

The Panasonic Plasma Display (Pasko) case is a landmark ruling that meticulously navigates the treacherous legal terrain of disguised contract labor and illegal worker dispatch. It sets a high bar for workers seeking to establish an implied employment contract directly with a client company based on the client's operational control. However, it also sends a clear message that client companies engaging in retaliatory conduct against workers who expose illegal practices can be held liable for damages, even if no direct, ongoing employment relationship is ultimately found by the court. The decision remains a key reference point, though its application must be considered alongside subsequent significant reforms to Japan's worker dispatch legislation.