Directors' Mandate in Corporate Bankruptcy: Japanese Supreme Court Rules on "Interest to Sue" in Dismissal Disputes

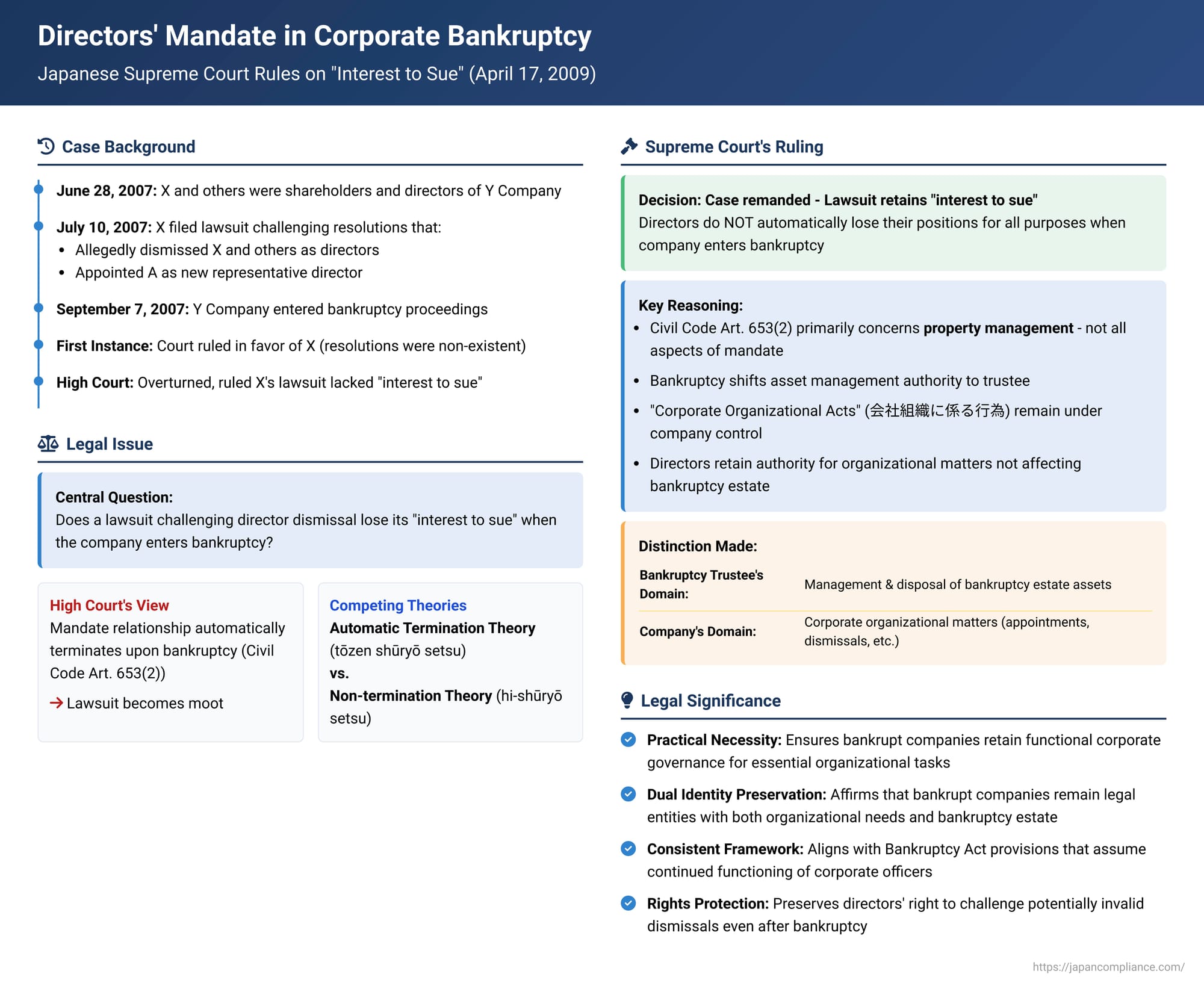

On April 17, 2009, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered an important judgment clarifying the status of company directors following the company's entry into bankruptcy proceedings. The Court ruled that a lawsuit challenging the validity of a shareholders' resolution dismissing directors does not automatically lose its "interest to sue" (a legal concept similar to standing or mootness) merely because the company subsequently becomes bankrupt. This decision hinged on the Court's interpretation that the mandate relationship between a company and its directors does not entirely terminate for all purposes upon the company's bankruptcy.

The Dispute Over Directorship and Subsequent Bankruptcy

The plaintiffs, X and others, were shareholders and, as of June 28, 2007, also incumbent directors of Y Company. On July 10, 2007, they initiated a lawsuit seeking legal confirmation of the non-existence of certain corporate resolutions. Specifically, they challenged:

- An alleged extraordinary shareholders' meeting resolution of Y Company, purportedly held on June 28, 2007. This resolution reportedly dismissed X and others from their director positions, removed B as an auditor, and appointed new individuals, including A (who later intervened in the lawsuit on behalf of Y Company), as directors and an auditor.

- An alleged board of directors' resolution, supposedly held by these newly appointed directors on the same day, which appointed A as the representative director of Y Company.

While this lawsuit was pending before the Fukushima District Court, Y Company entered formal bankruptcy proceedings on September 7, 2007, and a bankruptcy trustee was duly appointed. The first instance court eventually ruled in favor of X and others, finding the challenged resolutions to be non-existent.

However, A, the intervenor, appealed this decision. The Sendai High Court overturned the first instance judgment and dismissed the lawsuit initiated by X and others, concluding that it lacked a sufficient "interest to sue." The High Court's reasoning was that once Y Company entered bankruptcy and a trustee was appointed, the mandate (agency) relationship between Y Company and any of its directors at that time automatically terminated by operation of law (specifically, citing Article 653, item 2 of the Civil Code, which states that a mandate terminates upon the principal's bankruptcy). Therefore, the High Court reasoned, even if X and others were to win their lawsuit and the resolutions dismissing them were declared non-existent, they could not be reinstated to their former directorial positions. Absent any special circumstances, their legal challenge had become moot. X and others then successfully petitioned the Supreme Court to hear their appeal.

The Central Legal Question: Directors' Status After Company Bankruptcy

The pivotal legal question before the Supreme Court was the effect of a company's bankruptcy on the status of its directors, particularly in relation to the "interest to sue" in a pending lawsuit concerning their dismissal. The interpretation of Article 653, item 2, of the Civil Code was central to this issue. If this provision meant that directors automatically and entirely lost their positions upon the company's bankruptcy, then a lawsuit aimed at confirming their status or challenging their dismissal might indeed lose its practical legal purpose.

This issue had been a subject of debate among legal scholars. One view, the "automatic termination theory" (tōzen shūryō setsu), traditionally prevalent among company law experts, held that a director's mandate, being a form of agency, would automatically end with the company's (principal's) bankruptcy. Another view, the "non-termination theory" (hi-shūryō setsu), argued that the termination of the mandate upon the principal's bankruptcy primarily relates to acts concerning the management and disposal of property, which become the responsibility of the bankruptcy trustee. Under this latter view, the mandate could continue for other types of acts, particularly those related to the company's internal organization.

The Supreme Court's Clarification on Mandate and Interest to Sue

The Supreme Court reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings, finding that the lawsuit did retain its interest to sue.

The Court provided a nuanced interpretation of Civil Code Article 653, item 2:

- Purpose of the Civil Code Provision: The Court explained that the rule stipulating the termination of a mandate upon the principal's bankruptcy is based on the rationale that, once a principal enters bankruptcy, they lose the capacity to manage or dispose of their property themselves. Consequently, the agent (e.g., a director) also cannot perform such property-related acts on behalf of the principal. Thus, a typical mandate agreement, insofar as it concerns the principal's property-related affairs, ends because its objective can no longer be achieved by the agent.

- Distinction in Corporate Bankruptcy: When a company enters bankruptcy proceedings, the authority to manage and dispose of the assets constituting the bankruptcy estate shifts exclusively to the court-appointed bankruptcy trustee.

- "Corporate Organizational Acts": However, the Court emphasized that acts relating to the company's own organization (会社組織に係る行為 - kaisha soshiki ni kakaru kōi)—such as the appointment or dismissal of company officers (directors, auditors, etc.)—are distinct from the management and disposal of the bankruptcy estate. These organizational acts do not fall within the scope of the bankruptcy trustee's powers but are matters that the bankrupt company itself can, and must, still carry out through its corporate organs.

- Consequence for Directors' Mandate: In light of this distinction and the purpose of Civil Code Article 653, the Supreme Court concluded that the mandate relationship between a company and its directors or auditors does not automatically and entirely terminate merely because the company has entered bankruptcy proceedings. Directors who were in office at the time bankruptcy proceedings commenced do not automatically lose their positions for all purposes. They can continue to exercise their authority with respect to matters such as these corporate organizational acts. In support of this, the Court referenced its prior First Petty Bench judgment of June 10, 2004 (Heisei 12 (Ju) No. 56), which reached a similar conclusion regarding directors of a yugen kaisha (a form of limited liability company).

Therefore, because the directorships of X and others would not have automatically ceased for all functions upon Y Company's bankruptcy, their lawsuit challenging the validity of the resolutions that purported to dismiss them and appoint new officers retained its legal interest. The High Court's premise that they could not regain their positions was incorrect.

Implications for Bankrupt Companies and Their Governance

This Supreme Court decision has significant implications for the governance of companies in bankruptcy in Japan. It clarifies that a bankrupt company is not merely a passive collection of assets to be administered by a trustee; it remains a legal entity that requires functioning corporate organs for certain non-estate-related corporate activities.

The ruling supports the practical necessity of allowing incumbent directors to continue handling essential organizational tasks. As legal commentary points out, finding new individuals willing to serve as directors of a company already in bankruptcy can be extremely difficult. Moreover, the existing directors are typically the most familiar with the company's affairs and are often best positioned to undertake necessary corporate actions that fall outside the trustee's primary role of managing the bankruptcy estate. Such actions might include convening shareholder meetings, responding to lawsuits concerning the company's corporate structure, or taking steps related to the company's legal existence that do not impinge upon the trustee's administration of assets.

Consistency with Existing Bankruptcy Law Principles

The Supreme Court's interpretation is also consistent with various provisions within the Japanese Bankruptcy Act itself, which presuppose the continued existence and functioning of a bankrupt company's officers. For example, the Act assigns certain duties and rights to directors or other representatives of a bankrupt corporation, such as the obligation to provide explanations to the court or trustee, the right to file an immediate appeal against the bankruptcy adjudication decision itself, and roles in the claim investigation process. These provisions would be difficult to operationalize if all officers automatically lost their positions entirely upon the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings.

Concluding Thoughts

The Supreme Court's April 17, 2009, judgment provides a vital clarification on the status of directors when a Japanese company enters bankruptcy. By interpreting Civil Code Article 653, item 2, not as an absolute rule of mandate termination for all purposes, but as one primarily linked to the capacity to manage property, the Court ensured that bankrupt companies can continue to undertake necessary internal corporate organizational acts through their existing directors. This preserves the legal interest in lawsuits concerning the legitimate appointment or dismissal of such officers, even if the company's financial assets are under the control of a bankruptcy trustee. While the precise scope of "corporate organizational acts" for which directors retain authority may require further delineation in future cases, this decision marks an important step in understanding the nuanced interplay between corporate governance, agency law, and bankruptcy proceedings in Japan.