Directors' Liability for Company's Legal Breaches: A Japanese Supreme Court Look at the Scope of "Laws," Intent, and Negligence

Case: Shareholder Derivative Action Seeking Recovery for Loss Compensation by Directors, and Application for Joinder in Co-litigation

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of July 7, 2000

Case Number: (O) No. 270 of 1996

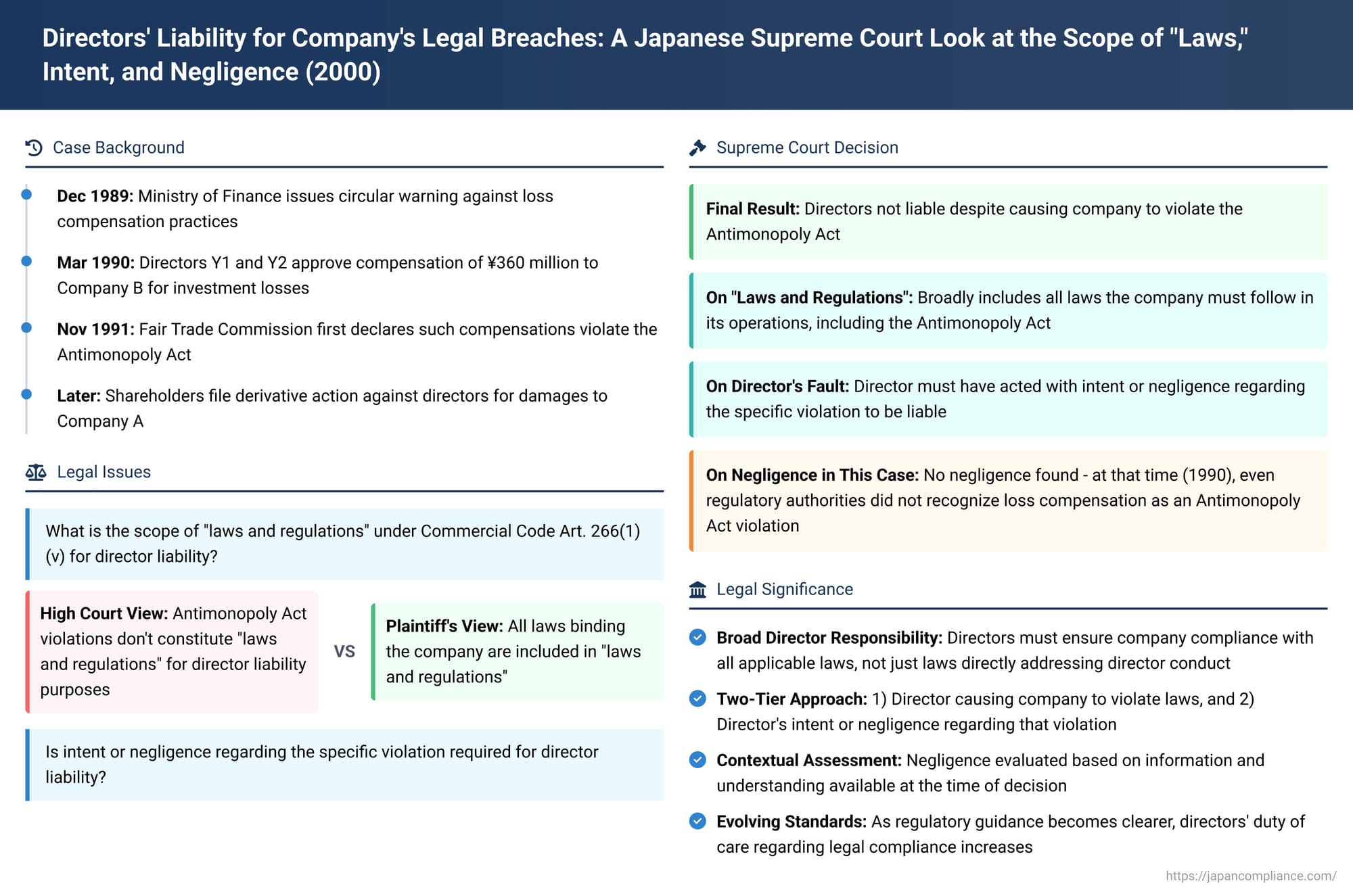

Directors are entrusted with managing a company's affairs, a responsibility that inherently includes ensuring the company operates within the bounds of the law. But what happens when a director's actions cause the company to violate a law? Under what circumstances can directors be held personally liable to the company for the resulting damages? A pivotal Japanese Supreme Court decision on July 7, 2000, arising from the securities loss compensation scandals of the early 1990s, provided critical clarification on two key aspects: the breadth of "laws and regulations" for which directors must ensure compliance, and the necessity of proving the director's intent or negligence concerning such violations.

The Loss Compensation and Its Aftermath: Facts of the Case

The case involved Company A, one of Japan's largest securities firms. Company A managed a type of discretionary investment account known as an "eigyo tokkin" for a major corporate client, Company B. In this arrangement, Company C Trust Bank acted as the trustee, but Company A effectively directed the investments. This specific "eigyo tokkin" operated without a formal investment advisory contract between Company B and an independent investment advisor, meaning Company A had significant influence over the investment strategy.

In December 1989, amidst growing concerns about certain practices in the securities industry, Japan's Ministry of Finance (MOF) issued an important circular. This circular urged securities firms to strictly refrain not only from legally prohibited practices like guaranteeing against investment losses to solicit business, but also from providing ex post facto (after the fact) compensation for losses or offering other special financial benefits to clients. The circular also stated that "tokkin" accounts should, as a general rule, be based on an investment advisory contract between the client and an investment advisory firm.

Following this MOF Circular, an employee of Company A, D, entered into negotiations with Company B to unwind its "eigyo tokkin" account. However, these negotiations were unsuccessful. D reported to Director Y1, who was the head of Company A's management division, that failing to compensate Company B for its investment losses could severely jeopardize their future business relationship.

Company B's "eigyo tokkin" account had been incurring losses even during periods when the stock market was generally buoyant. Director Y1, taking into account this history and the significant risk that Company A might lose its lucrative position as lead underwriter for Company B's future securities offerings, concluded that compensating Company B for its losses was necessary.

In March 1990, the executive committee of Company A, which included the defendants Y1 and Y2 (who were representative directors), approved a proposal to compensate Company B and other clients for their losses. Notably, when making this decision, the directors did not seek legal opinions from lawyers or other experts regarding the potential illegality of such loss compensation, particularly under laws beyond the immediate scope of securities regulations. Company A subsequently executed the loss compensation for Company B, effectively making Company B whole for losses amounting to approximately 360 million yen. This was achieved through a sale and immediate repurchase of foreign currency warrants, structured to avoid direct market impact.

Shareholders of Company A (the plaintiffs, X) later filed a shareholder derivative lawsuit. They alleged that the defendants, Y1, Y2, and other directors, by authorizing and implementing this loss compensation, had breached their duties as directors and caused financial damage to Company A. The suit was based on Article 266, Paragraph 1, Item 5 of the then-Commercial Code (a provision establishing director liability for damages caused by acts violating "laws and regulations" or the articles of incorporation, the substance of which is now part of Article 423, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act).

Lower Court Rulings: A Narrow View of "Laws"

The court of first instance (Tokyo District Court, judgment dated September 16, 1993) dismissed the shareholders' claim.

The appellate court (Tokyo High Court, judgment dated September 26, 1995) also dismissed the claim, but with notable reasoning. The High Court found that the loss compensation provided by Company A to Company B did indeed violate Article 19 of Japan's Antimonopoly Act (which prohibits unfair trade practices), specifically falling under "undue inducement of customers" as per General Designation No. 9 issued by the Fair Trade Commission (FTC). However, the High Court then concluded that a violation of the Antimonopoly Act did not constitute a violation of "laws and regulations" within the meaning of Article 266, Paragraph 1, Item 5 of the Commercial Code for the purpose of establishing director liability. The shareholders appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Broad Interpretation and Exoneration

The Supreme Court dismissed the shareholders' appeal, ultimately agreeing with the lower courts' conclusion that the directors were not liable. However, it did so based on significantly different reasoning, particularly regarding the scope of "laws" and the requirement of director fault.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: A Three-Part Analysis

The Supreme Court's judgment addressed three crucial points:

Part I: The Expansive Scope of "Laws and Regulations" (法令 - hōrei)

The Court first tackled the High Court's narrow interpretation of "laws and regulations."

- It affirmed that "laws and regulations" in Article 266(1)(v) clearly include general provisions defining directors' fundamental duties to the company, such as the duty of care (then Article 254, Paragraph 3 of the Commercial Code, referencing Civil Code Article 644) and the duty of loyalty (then Article 254-3 of the Commercial Code; now respectively Companies Act Articles 330 and 355). Specific statutory provisions detailing particular director duties are also included.

- Crucially, the Supreme Court held that "laws and regulations" under this provision also encompass all provisions in the Commercial Code and other statutes and ordinances that are addressed to the company itself and which the company is obligated to comply with in the course of conducting its business.

- The rationale for this broad interpretation was straightforward: A company, as a legal entity, is naturally bound to comply with all applicable laws. Directors are the individuals responsible for determining the company's business execution and for carrying it out. Therefore, it is an intrinsic part of a director's duty to the company to ensure that the company does not violate these laws.

- Consequently, if a director's actions cause the company to violate such a law (one directed at the company's conduct), that director's act is considered a violation of "laws and regulations" for the purpose of Article 266(1)(v). This is true regardless of whether the act also constitutes a breach of the director's general duties of care or loyalty.

- Applying this to the current case, Article 19 of the Antimonopoly Act, which prohibits businesses (including companies like Company A) from engaging in unfair trade practices, is unequivocally a law that companies must observe in their operations. Thus, the act of the defendant directors in causing Company A to provide the loss compensation (which the Supreme Court agreed was an unfair trade practice violating the Antimonopoly Act) did constitute an act violating "laws and regulations" under Article 266(1)(v). The High Court, therefore, had erred in its narrow interpretation of this term.

Part II: The Indispensable Element of Director's Fault (Intent or Negligence)

Having established that the directors' actions did involve a violation of "laws," the Supreme Court then addressed the standard of fault required for liability.

- It held, citing a previous Supreme Court precedent (a Third Petty Bench judgment of March 23, 1976), that for a director to be held liable for damages under Article 266(1)(v) due to an act violating laws or the articles of incorporation, it must be shown that the director acted with intent (故意 - koi) or negligence (過失 - kashitsu) with respect to that specific violation.

Part III: No Negligence Found in This Specific Instance

The Supreme Court then examined whether the defendant directors were intentional or negligent concerning the violation of the Antimonopoly Act. It relied on the factual findings of the High Court, which included:

- The defendant directors were primarily concerned about whether the loss compensation would violate the Securities and Exchange Act or the MOF Circular. They did not specifically consider the implications under the Antimonopoly Act, largely because the act of compensating an existing major client for past losses was not perceived as a typical act of soliciting business from the general investing public (which is a common focus of unfair competition concerns).

- This lack of focus on Antimonopoly Act implications was not unique to the defendants. Relevant regulatory authorities, including the MOF, primarily approached issues in the securities market through the lens of securities laws. The question of whether loss compensation by securities firms might violate the Antimonopoly Act was not a prominent issue or subject of regulatory guidance for more than a year and a half after Company A made the compensation payment in March 1990.

- Even the Fair Trade Commission (FTC), the primary enforcer of the Antimonopoly Act, did not initially take the position that such loss compensation practices violated the Act. It was only in November 1991 (well after the events in question) that the FTC issued an official recommendation stating that a series of loss compensations by securities firms, including the one by Company A, constituted unfair trade practices in violation of Article 19 of the Antimonopoly Act.

Based on these specific historical circumstances, the Supreme Court concluded:

- At the time the defendant directors decided upon and implemented the loss compensation (March 1990), there were "unavoidable reasons" (yamu o enai jijō) for their failure to recognize that their actions would constitute a violation of the Antimonopoly Act.

- Therefore, it could not be said that they were negligent in lacking this specific awareness.

- Although the loss compensation did violate the Antimonopoly Act (and thus "laws" for the purpose of director liability), the directors could not be held liable under Article 266(1)(v) because they lacked the requisite intent or negligence regarding that specific violation.

Thus, while disagreeing with the High Court's reasoning on the scope of "laws," the Supreme Court ultimately affirmed its conclusion that the directors were not liable, albeit on different grounds.

Analysis and Implications: A Landmark Decision on Director Duties

This 2000 Supreme Court judgment provided critical clarifications on director liability in Japan, with lasting implications.

- The "Scope of Laws" – A Broad Embrace:

The Court's adoption of the "non-restrictive view" (非限定説 - hi-gentei setsu) regarding the scope of "laws and regulations" was a significant development. It confirmed that directors have a duty to ensure the company complies not just with laws directly addressing director conduct (like duties of care and loyalty) but with the entire corpus of laws governing the company's business operations.

Prior to this, some legal scholars and, as seen in this case, some lower courts, had advocated for a more "restrictive view" (限定説 - gentei setsu), partly out of concern that an overly broad definition might lead to an unmanageable scope of director liability. However, as noted in a supplementary opinion by Justice Kawai in this very case, even under a restrictive interpretation of "laws" for Article 266(1)(v), directors could still potentially be held liable for causing the company to violate other laws if doing so constituted a breach of their general duty of care. The Supreme Court's broad interpretation can be seen as reflecting principles of corporate social responsibility, the protection of wider societal interests that laws aim to safeguard, or the presumed reasonable expectations of shareholders that the company will operate lawfully.

While the direct impact of this specific "scope of laws" debate has somewhat diminished under the current Companies Act (which consolidated director liability primarily under the umbrella of "breach of duties" in Article 423), the underlying principle that directors are responsible for company-wide legal compliance remains. The distinction can still be relevant in procedural aspects, such as the allocation of the burden of proof. - The Structure of Liability for Causing Company to Breach Specific Laws:

The judgment establishes a two-tiered approach:This structure, particularly regarding the burden of proof for negligence, has been a subject of academic discussion. The Supreme Court's stance implies that once the plaintiff (e.g., shareholders in a derivative suit) proves the factual occurrence of the company's legal violation resulting from the director's decision, the burden may effectively shift to the director to demonstrate their lack of intent or negligence regarding that violation. An alternative strong academic viewpoint, rooted in treating director liability as a special form of contractual (mandate) liability, would argue that the plaintiff must prove not only the company's violation but also that this violation stemmed from the director's negligent failure to exercise due care (i.e., the plaintiff bears the burden of proving the director's negligence). The Supreme Court's approach is generally seen as more favorable to plaintiffs in derivative suits and is thought to encourage a higher standard of legal compliance by directors, as the onus is on them to justify their lack of awareness or intent regarding a legal breach.- Breach of Law: If a director's actions cause the company to violate a specific law applicable to the company's operations, this directly constitutes an "act violating laws" by the director for liability purposes. There is no need to independently prove that this act also breached the director's general duty of care or loyalty.

- Director's Fault: However, for the director to be held personally liable for the resulting damages, it must also be demonstrated that the director acted with intent or negligence concerning that specific legal violation.

- Fault Regarding "Illegality Awareness":

The exoneration of the directors in this specific case hinged on their lack of culpable awareness of the illegality of their actions under the Antimonopoly Act at that particular time. The fact that neither other regulatory bodies nor the FTC itself had yet characterized such loss compensations as Antimonopoly Act violations was crucial. It underscored that the standard of negligence is contextual. While the directors did not seek specific legal advice on the Antimonopoly Act implications (a point noted by some commentators as a potential oversight), the Supreme Court found that even if they had, given the prevailing understanding at the time, they likely would not have been alerted to this specific legal risk. - Other Defenses and Evolving Standards:

Beyond lack of intent or negligence, directors might also raise defenses such as justification (e.g., acts of necessity) or excuse (e.g., duress leading to a lack of "expectability" of lawful conduct). For instance, a 2006 Supreme Court case considered (but ultimately rejected on the facts) a defense of duress for payments made to anti-social forces.

It's also important to note that societal expectations regarding corporate compliance have significantly increased since 1990. As legal awareness grows and regulatory guidance becomes clearer, it may become increasingly difficult for directors to successfully argue a lack of negligence for failing to recognize the illegality of certain actions. Acts that clearly violate established laws, even if perceived to be in the company's (or shareholders') short-term financial interest, are unlikely to be excused.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision of July 7, 2000, is a landmark ruling in Japanese corporate law. It broadly defines the "laws and regulations" for which directors must ensure company compliance, encompassing all rules governing the company's business activities. Simultaneously, it confirms that director liability for causing the company to breach these laws is not strict; it requires a finding that the director acted with intent or negligence with respect to the specific violation.

This case uniquely illustrates that even if a corporate action is later determined to be illegal, directors may escape personal liability if, at the time the action was taken, its illegality under a particular statute was not reasonably apparent, even to the relevant regulatory authorities. It underscores that the assessment of a director's fault is highly dependent on the specific factual and legal environment existing at the moment of their decision-making. While providing a degree of protection for directors acting in then-uncharted legal territory, the case also implicitly reinforces the ever-growing importance of proactive legal compliance and due diligence in corporate management.