Directors in the Dust? Japanese Supreme Court on Director Status After Company Bankruptcy

Date of Judgment: April 17, 2009

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

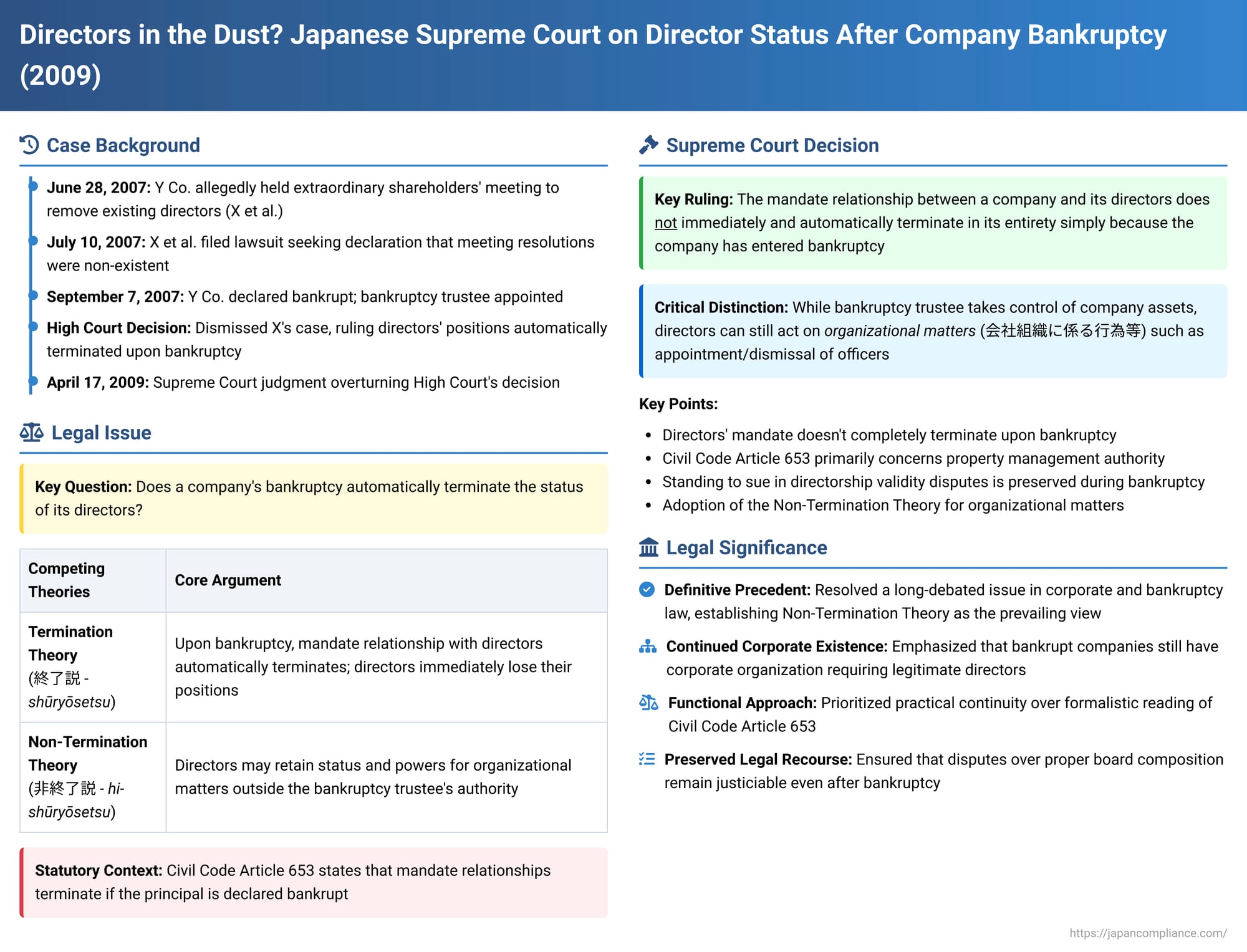

When a company is declared bankrupt, the immediate focus shifts to the administration of its assets by a bankruptcy trustee. But what becomes of the company's directors? Do their powers and positions automatically dissolve the moment bankruptcy proceedings commence? This question is not merely academic; it has significant implications, especially if there are ongoing legal disputes concerning who the rightful directors of the company are.

The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this critical issue in its decision on April 17, 2009, clarifying the status of directors and their mandate relationship with a company once it enters bankruptcy.

The Legal Background: Mandate Relationships and Bankruptcy in Japan

In Japanese law, the relationship between a company and its directors is understood as a form of mandate (委任 - inin) governed by the Civil Code, in addition to specific provisions in the Companies Act. A key provision in the Civil Code, Article 653, generally states that a mandate relationship terminates if the principal (in this context, the company) is declared bankrupt.

This statutory provision had historically led to two main contending legal theories regarding the status of company directors upon the company's bankruptcy:

- The Termination Theory (終了説 - shūryōsetsu): This theory posits that upon the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings against a company, the mandate relationship with its directors automatically terminates. Consequently, the directors immediately lose their positions and powers. This view found some support in a literal reading of the statutes and concerns about allowing directors who may have led the company into insolvency to continue in any official capacity.

- The Non-Termination Theory (非終了説 - hi-shūryōsetsu): This theory argues that the mandate relationship does not automatically and entirely terminate. Proponents suggest that while directors lose powers related to the company's assets (which fall under the bankruptcy trustee's control), they may retain their status and certain powers related to non-asset-based, purely organizational matters of the company.

The Supreme Court's 2009 decision provided significant clarity in this debate.

Facts of the Y Co. Case

The case involved a dispute over the legitimacy of directorship positions at Y Co.

- Disputed Shareholders' Meeting: On June 28, 2007, Y Co. allegedly held an extraordinary shareholders' meeting. At this meeting, resolutions were purportedly passed to remove the existing directors, X et al. (plaintiffs/appellants), and an auditor, B, and to appoint new directors and auditors. Subsequently, the allegedly newly appointed board was said to have held a meeting to appoint a new representative director.

- Lawsuit by Allegedly Ousted Directors: On July 10, 2007, X et al. filed a lawsuit seeking a judicial declaration that these shareholders' meeting resolutions and the subsequent board resolution were, in fact, non-existent (e.g., due to fatal flaws in how the meeting was called or conducted).

- Company Declared Bankrupt: While this lawsuit was pending in the first instance court, Y Co. was declared bankrupt on September 7, 2007, and a bankruptcy trustee was appointed to manage its affairs.

- High Court's Dismissal Based on Termination Theory: The High Court, when the case reached it on appeal, adopted the "termination theory." It reasoned that upon Y Co.'s bankruptcy, any mandate relationship between the company and its directors (whether the old ones or the allegedly new ones) would have automatically terminated. Therefore, even if X et al. were to win their lawsuit and prove the resolutions were non-existent, they could not be reinstated as directors because their own mandates would also have ceased at the point of bankruptcy. Consequently, the High Court concluded that X et al. no longer had a legal interest or "standing to sue" (訴えの利益 - uttae no rieki), and dismissed their case.

X et al. appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision of April 17, 2009

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous judgment, overturned the High Court's decision.

Reinterpreting Civil Code Article 653 in the Corporate Context

The Court began by analyzing the purpose behind Civil Code Article 653, which dictates the termination of a mandate upon the principal's bankruptcy.

- The Court reasoned that the primary rationale for this rule is linked to the principal's loss of capacity to manage or dispose of their property following bankruptcy. If the principal (the company) can no longer independently manage its property, then the agent (the director) similarly cannot exercise mandated powers over that property. Thus, a typical mandate concerning the mandator's property naturally cannot achieve its purpose and must end.

- When a company enters bankruptcy, the authority to manage and dispose of the company's assets—collectively forming the "bankruptcy estate"—vests exclusively in the bankruptcy trustee.

- However, the Court drew a crucial distinction for acts purely related to the company's organization and corporate structure (会社組織に係る行為等 - kaisha soshiki ni kakaru kōi tō). These include matters such as the appointment or dismissal of directors and auditors. Such organizational acts, the Court stated, are distinct from the management and disposal of the bankruptcy estate and do not fall under the bankruptcy trustee's powers. These acts can, in principle, still be performed by the bankrupt company itself, acting through its appropriate corporate organs.

Adoption of the Non-Termination Theory for Organizational Matters

Based on this nuanced interpretation of the purpose of Civil Code Article 653, the Supreme Court held that:

- The mandate relationship between a company and its directors (or auditors) does not immediately and automatically terminate in its entirety simply because the company has received a bankruptcy procedure commencement decision.

- Consequently, directors who were in office at the time the company was declared bankrupt do not automatically lose their status and all their powers. They can continue to exercise their authority as directors specifically with respect to matters concerning the company's organization. In making this point, the Supreme Court referenced its own prior ruling from 2004 (Heisei 16), which had supported the view that directors retain their status for such non-property related organizational acts post-bankruptcy.

Standing to Sue is Preserved

Flowing from this adoption of the non-termination theory for organizational matters, the Supreme Court concluded:

- If a lawsuit is pending at the time of a company's bankruptcy, and that lawsuit concerns the validity of shareholders' meeting resolutions for the dismissal or appointment of directors or auditors, the plaintiff's legal interest (standing) in pursuing that lawsuit is not automatically extinguished by the bankruptcy.

- The question of who the rightful directors are remains a live and relevant issue, precisely because those directors may still have legitimate organizational functions to perform, even for a bankrupt company.

Outcome: The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in its interpretation of the law by incorrectly assuming that directors automatically lose their positions upon the company's bankruptcy, which led to the erroneous conclusion that X et al. had lost their standing to sue. The Supreme Court, therefore, quashed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for a trial on the merits of X et al.'s claim that the disputed shareholders' meeting resolutions were non-existent.

Significance and Implications of the Ruling

The 2009 Supreme Court decision provided significant clarification on a long-debated point of Japanese corporate and bankruptcy law.

- Definitive Stance on Director Status in Bankruptcy: The ruling firmly established the non-termination theory as the prevailing view regarding the immediate impact of a company's bankruptcy on the status of its directors, at least concerning their ability to act on purely organizational matters. This resolved much of the uncertainty that had existed due to seemingly conflicting earlier judicial dicta.

- Continued Relevance of Corporate Governance Post-Bankruptcy: The decision underscores that a bankrupt company, while its assets are managed by a trustee, continues to have a corporate existence. There may still be a need for its legitimate directors to perform functions related to its corporate structure. These could include cooperating with the bankruptcy trustee, addressing shareholder inquiries on non-estate matters, or, in certain circumstances, participating in discussions about potential corporate rehabilitation or other post-bankruptcy organizational steps.

- Rationale Supporting Non-Termination: Academic commentary highlights several practical and policy reasons that support the non-termination theory adopted by the Court:

- Practical Difficulties: Appointing entirely new directors for a company already in bankruptcy can be practically challenging.

- Need for Continuity and Knowledge: Existing directors often possess crucial institutional knowledge about the company's affairs, which can be valuable even during the bankruptcy process for tasks not directly related to asset administration.

- Focus of Civil Code Art. 653: The Court’s interpretation aligns with a view that Civil Code Art. 653 is primarily concerned with the termination of mandates related to property management, which becomes impossible for the bankrupt principal, rather than all aspects of a director’s role.

- Distinction from the Stricter "Termination Theory": The Supreme Court’s reasoning effectively narrows the application of Civil Code Art. 653 in the context of corporate directors, moving away from a purely formalistic reading that would see all directorial mandates instantly cease. It prioritizes a functional approach, considering what powers directors might still reasonably exercise outside the scope of the bankruptcy trustee's authority over assets.

Conclusion

The April 17, 2009, Supreme Court decision marked a significant development in Japanese law by clarifying that the commencement of bankruptcy proceedings against a company does not automatically and completely terminate the mandate of its directors or extinguish their status for all purposes. Directors may retain their positions and authority to act on organizational matters that are distinct from the bankruptcy trustee's administration of the company's assets.

This ruling ensures that legal disputes concerning the legitimate composition of a company's board of directors remain relevant and can be adjudicated even after the company has entered bankruptcy. It acknowledges the continuing, albeit limited, role that directors might play in the life of a bankrupt company and upholds the importance of resolving questions of proper corporate governance regardless of the company's financial state.