Director's Duty to the World? A Deep Dive into Japanese Supreme Court's View on Third-Party Liability

Case: Action for Damages

Supreme Court of Japan, Grand Bench, Judgment of November 26, 1969

Case Number: (O) No. 1175 of 1964

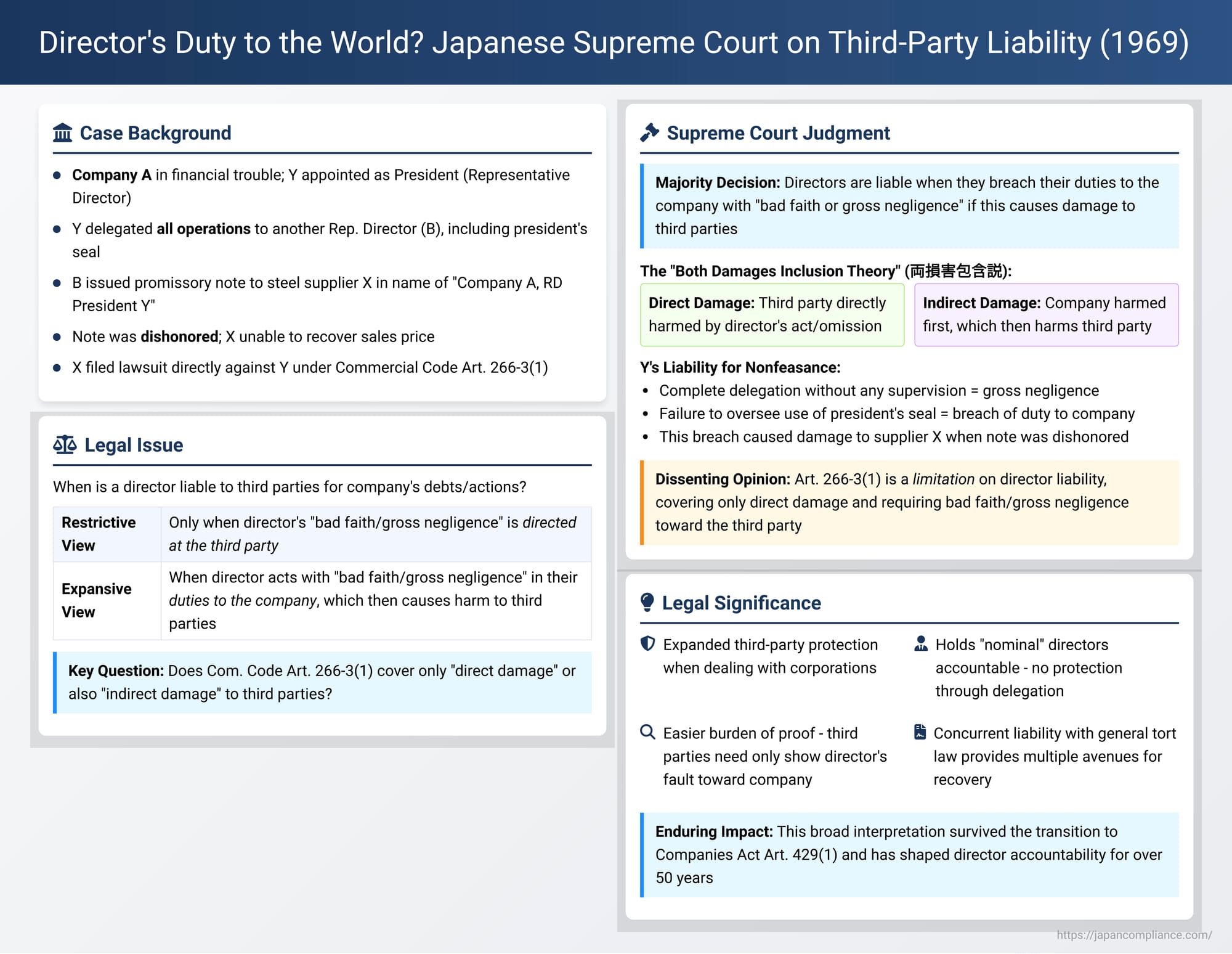

Directors of corporations hold a position of trust and responsibility, not only towards their company and its shareholders but also, in certain circumstances, towards third parties who may be harmed by their actions or inactions. Japanese company law provides a specific statutory basis for such third-party liability. A seminal Grand Bench judgment by the Supreme Court on November 26, 1969, provided a foundational and expansive interpretation of this liability, particularly concerning the meaning of "bad faith or gross negligence" attributable to directors and the types of damages recoverable by third parties. This ruling has had a lasting impact on how director accountability to external stakeholders is understood in Japan.

A Dishonored Note and a Hands-Off President: Facts of the Case

The case arose from a commercial transaction involving Company A, which was experiencing financial difficulties. To leverage his personal status and creditworthiness for the struggling company, Y was appointed as a Representative Director and President of Company A. However, Y was a busy individual and effectively delegated the entirety of Company A's business operations to another Representative Director, B. This delegation included entrusting B with the president's official seal and Y's personal name stamp, granting B the authority to issue promissory notes and checks in the name of "Company A, Representative Director President Y."

B, acting on behalf of Company A, purchased steel materials from X (the plaintiff). For payment, B issued a promissory note to X, drawn in the name of "Company A, RD President Y." Subsequently, this promissory note was dishonored, meaning Company A failed to make payment when it fell due. As a result, X was unable to recover the sales price for the steel materials supplied.

X then filed a lawsuit directly against Y, the figurehead RD President, seeking damages. X's primary legal basis was an alleged joint tort committed by Y and B. Alternatively, X claimed Y was liable under then-Commercial Code Article 266-3, Paragraph 1 (the predecessor to Article 429, Paragraph 1 of the current Companies Act), which established a framework for directors' liability to third parties. X also asserted liability under the Civil Code for failure to supervise an agent.

The Lower Courts: Finding Liability

Both the Osaka District Court (court of first instance) and the Osaka High Court (appellate court) found Y liable to X. Their decisions were primarily based on Y's breach of duties under Commercial Code Article 266-3, Paragraph 1. However, both courts also applied the doctrine of comparative negligence, reducing the amount of damages awarded to X to some extent. Y, disagreeing with the finding of liability, appealed to the Supreme Court. The case was elevated to the Grand Bench due to its legal significance.

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench Decision: Affirming Broad Director Accountability to Third Parties

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench, in a majority decision, dismissed Y's appeal, thereby upholding his liability to X. The majority opinion laid out a comprehensive interpretation of Article 266-3, Paragraph 1 of the then-Commercial Code.

Reasoning of the Majority Opinion: Protecting Third Parties via Director's Internal Duties

The majority's reasoning can be broken down into several key components:

- Nature and Purpose of the Statutory Liability (Art. 266-3(1)):

The Court emphasized that the legislature, recognizing the crucial role stock companies play in the economy and the dependence of corporate activities on the actions of their directors, established this provision specifically for the protection of third parties. It stipulated that if directors, in the performance of their duties, breached their obligations to the company (such as the general duty of care and the specific duty of loyalty) with "bad faith or gross negligence" (悪意又は重大な過失 - akui matawa jūdai na kashitsu), and this breach thereby caused damage to a third party, those directors would be directly liable to compensate the third party for such damage. - Scope of Damage Covered – The "Both Damages Inclusion Theory" (両損害包含説 - ryō songai hōgan setsu):

A critical aspect of the ruling was its interpretation of the type of third-party damage covered. The Court held that this liability applies regardless of whether the third party suffered direct damage (損害を被った結果、ひいて第三者に損害を生じた場合 - where the company suffers damage which, in turn, causes damage to the third party, often termed "indirect damage") or suffered damage directly (直接第三者が損害を被った場合 - where the director's act directly harms the third party, even if the company itself suffers no loss). This broad interpretation became known as the "both damages inclusion theory." - Relationship with General Tort Law (Civil Code Article 709):

The majority opinion clarified that this special statutory liability under the Commercial Code does not preclude a director from also being held liable under general tort law (Civil Code Article 709) if their conduct constitutes a direct tort against the third party. A general tort claim would typically require proving the director's intent or (simple) negligence specifically directed towards harming the third party.

However, Article 266-3(1) provided an alternative, and often easier, path for third parties. To succeed under this Commercial Code provision, the third party only needed to allege and prove the director's "bad faith or gross negligence" in breaching their duties to the company, and a causal link between that breach and the third party's damage. The third party did not need to separately prove that the director had intent or negligence specifically in relation to causing harm to them (the third party). - Liability for Negligent Supervision (Nonfeasance):

The Court addressed Y's situation directly. It held that if a representative director, such as Y, completely delegates all company business operations to another representative director (like B) or other individuals, takes no active interest in how those operations are being conducted, and consequently overlooks or fails to prevent misconduct or breaches of duty by those individuals, then that representative director (Y) is also deemed to have breached their own duties to the company with "bad faith or gross negligence." Essentially, abdicating supervisory responsibility to such an extent is, in itself, a grossly negligent breach of a director's duty. - Application to the Facts:

In Y's case, he had entrusted all operational authority, including the power to issue promissory notes in his name as RD President, to B. He had taken no steps to supervise B's activities. B, in turn, had issued the promissory note to X for the steel purchase at a time when Company A was in dire financial straits and payment was unlikely (this was B's misconduct/breach of duty to Company A, committed with at least gross negligence). Y's complete failure to supervise B, allowing this situation to occur, was deemed a gross dereliction of Y's own duties as RD President of Company A. This grossly negligent breach of duty by Y (to Company A) caused X (the third party) to suffer damage when the note was dishonored. Therefore, Y was held liable to X under Article 266-3, Paragraph 1.

The Dissenting View: A More Restricted Interpretation

The Grand Bench decision was not unanimous. Notably, Justice Matsuda penned a detailed dissenting opinion (joined by Justice Tanaka), arguing for a much more restrictive interpretation of Article 266-3, Paragraph 1:

- A Special Tort Rule Limiting Liability: The dissent viewed the provision not as an expansion of director liability but as a special rule of tort law that limits director liability to third parties. Specifically, it argued that directors should only be liable to third parties for their tortious acts if committed with "bad faith or gross negligence" towards the third party. This would mean that directors are exempted from liability for acts of simple negligence causing harm to third parties, a protection not afforded under general tort law (Civil Code Art. 709).

- Displacement of General Tort Law: Consequently, this special Commercial Code provision should displace the general tort rule for directors acting in their official capacity. There would be no concurrent liability under Civil Code Art. 709 for simple negligence.

- "Bad Faith or Gross Negligence" Pertains to Conduct Towards Third Party: The requisite "bad faith or gross negligence" must relate to the director's conduct that directly harmed the third party, not merely to an internal breach of duty owed to the company.

- Only "Direct Damage" Covered: The liability should be confined to "direct damage" inflicted upon the third party by the director's act, and should not extend to "indirect damage" (where the third party suffers because the company was harmed).

- Concerns about Scope: The dissent expressed concern that the majority's broad interpretation could lead to an unwarranted expansion of director liability, particularly for directors of the many small, often nominally incorporated, companies in Japan, where the corporate form might not reflect the robust internal structures presupposed by such extensive liability rules. It suggested that doctrines like "piercing the corporate veil" might be more appropriate for addressing issues in such small companies, rather than broadly reinterpreting general director liability provisions.

Analysis and Implications: Shaping Director Accountability to Third Parties

The 1969 Grand Bench ruling remains a foundational decision in Japanese corporate law concerning the liability of directors to third parties.

- Nature of the Liability – Special Statutory Duty: The majority established that the liability under what is now Companies Act Article 429, Paragraph 1 is a special statutory liability created by company law for the protection of third parties. While it can exist concurrently with general tort liability under the Civil Code, it has its own distinct requirements.

- The Crucial "Bad Faith or Gross Negligence" Standard: The most debated aspect was the referent of "bad faith or gross negligence." The majority's interpretation – that it refers to the director's state of mind or conduct concerning their duties owed to the company – significantly eases the burden of proof for third-party plaintiffs. If a director is found to have been grossly negligent in, for example, overseeing the company's financial reporting (a duty to the company), and this leads to misleading financial statements that cause a third-party investor to suffer loss, that investor can sue the director under Article 429(1) by proving the gross negligence towards the company, without needing to prove the director specifically intended to deceive that investor or was negligent towards that investor. This is often a lower hurdle than a standard tort claim.

- The "Both Damages Inclusion Theory" (Direct and Indirect Damage):

The Court's explicit inclusion of both "direct damage" (e.g., a third party is directly defrauded by a director's act) and "indirect damage" (e.g., a creditor is harmed because a director's mismanagement bankrupted the company) greatly expanded the potential scope of this liability. This has been particularly important for creditors of insolvent companies, providing them with a potential avenue to recover losses directly from culpable directors when the company itself is unable to pay.

Legal commentators have noted the theoretical challenge in squaring the "indirect damage" aspect with the requirement that the director's fault be in relation to their duty to the company. How does a breach of duty to the company that first harms the company, and then harms a creditor, directly equate to liability to that creditor? The prevailing explanations often involve concepts like: (a) a director's act that constitutes a tort against a third party also damages the company's social reputation or trust, thus being a breach of duty to the company; or (b) particularly when a company is nearing insolvency, directors take on a heightened duty to preserve company assets for the benefit of creditors, and a breach of this duty (a duty effectively to the company to protect creditor interests) can ground liability under Article 429(1). - Liability for Nonfeasance and Failure of Supervision: This case is a leading authority for the principle that a director, especially a representative director, cannot escape liability by simply abdicating their responsibilities and delegating all operational control to others without any oversight. Such complete nonfeasance, if it allows misconduct by subordinates that harms third parties, can itself constitute gross negligence in the performance of duties owed to the company, thereby triggering liability under Article 429(1). This principle extends, by analogy, to the supervisory duties of ordinary (non-representative) directors concerning the overall conduct of the company's business.

- Enduring Debate and Legislative Inaction:

Despite the clarity provided by the Grand Bench majority, the dissenting opinions, particularly Justice Matsuda's comprehensive critique, highlighted alternative, more restrictive interpretations that also had logical coherence. The fact that the legislature, in subsequent revisions of company law including the enactment of the 2005 Companies Act (which largely carried over the wording of Article 266-3(1) into Article 429(1)), did not fundamentally alter the operative language has meant that the majority view from this 1969 decision remains the prevailing law. However, the critiques regarding the potentially vast scope of liability and its theoretical underpinnings continue to be discussed in academic circles.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's Grand Bench decision of November 26, 1969, established a broad and impactful framework for understanding the liability of company directors to third parties in Japan. By interpreting the statutory requirement of "bad faith or gross negligence" as relating to the director's breach of duties owed to the company, and by including both direct and indirect damages suffered by third parties within the scope of recovery, the Court significantly empowered external stakeholders, particularly creditors of distressed or mismanaged companies. Furthermore, the ruling firmly established that directors cannot shield themselves from liability by merely being passive or "nominal" if their gross negligence in fulfilling their supervisory duties allows the company to harm third parties. While subject to ongoing academic debate regarding its theoretical foundations and ultimate scope, this judgment has undeniably shaped the landscape of director accountability in Japanese corporate law for over half a century.