Business Judgment Rule & Principle of Trust in Japan: A Practical Guide to Limiting Director Liability

Guide to Japan’s Business Judgment Rule and Principle of Trust—why sound process, delegation and documentation let directors limit personal liability.

TL;DR

- Japanese courts protect directors who make informed, rational, good‑faith decisions through the Business Judgment Rule (BJR).

- In large organisations, the Principle of Trust lets directors rely on competent subordinates unless “red flags” appear.

- Documented process, sound internal controls and prompt follow‑up on warnings are the keys to avoiding personal liability.

Table of Contents

- Director Duties under the Japanese Companies Act

- The Business Judgment Rule (BJR) in Japan: Protecting Decisions

- The Principle of Trust: Delegation in Large Organizations

- Application in Practice: Osaka District Court Decision (May 20 2022)

- Implications for U.S. Directors and Companies

- Conclusion

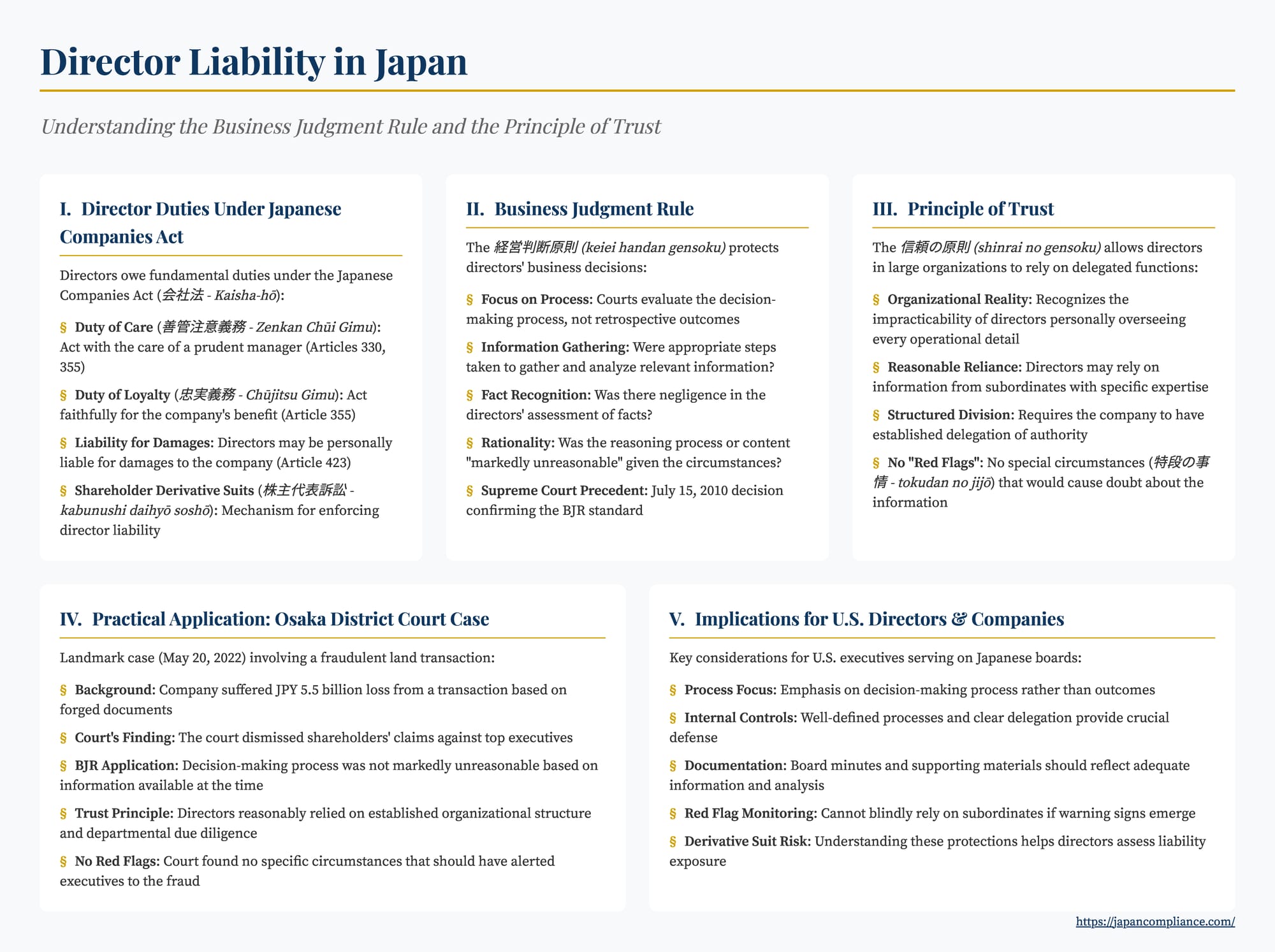

Serving as a director of a Japanese corporation, whether a large subsidiary of a U.S. parent or an independent entity, carries significant responsibilities. Directors owe duties of care and loyalty to the company, and breaches can lead to substantial personal liability, often pursued through shareholder derivative suits (株主代表訴訟 - kabunushi daihyō soshō). However, Japanese corporate law, like its counterparts elsewhere, recognizes that directors must be able to make difficult decisions and manage complex organizations without the constant fear of litigation over unsuccessful outcomes. Two key legal doctrines provide crucial protection in this regard: the Business Judgment Rule (経営判断原則 - keiei handan gensoku) and the Principle of Trust (信頼の原則 - shinrai no gensoku). Understanding these doctrines is vital for anyone involved in corporate governance in Japan.

Director Duties under the Japanese Companies Act

The foundation of director accountability lies in the Japanese Companies Act (会社法 - Kaisha-hō). Key duties include:

- Duty of Care (善管注意義務 - Zenkan Chūi Gimu): Directors are required to manage the company's affairs with the care of a prudent manager (Article 330 referencing the Civil Code; Article 355). This involves acting diligently and making informed decisions.

- Duty of Loyalty (忠実義務 - Chūjitsu Gimu): Directors must act faithfully for the benefit of the company (Article 355). This prohibits self-dealing and requires prioritizing the company's interests over personal ones.

Failure to meet these standards can result in directors being held liable for damages suffered by the company (Article 423). Shareholder derivative suits provide a mechanism for shareholders to sue directors on behalf of the company to recover such damages.

The Business Judgment Rule (BJR) in Japan: Protecting Decisions

Recognizing that business inherently involves risk and that not all decisions will lead to success, Japanese courts have developed and apply the Business Judgment Rule. This doctrine shields directors from liability for decisions made in good faith and on an informed basis, even if those decisions ultimately result in losses for the company.

Core Principles:

The focus of the BJR in Japan is primarily on the process of decision-making, rather than a retrospective evaluation of the decision's outcome. Courts generally refrain from second-guessing business decisions if the directors acted reasonably. Key questions courts ask when evaluating a decision under the BJR include:

- Information Gathering: Did the directors take reasonably appropriate steps to gather and analyze relevant information before making the decision?

- Fact Recognition: Was there negligence or gross error in the directors' understanding or assessment of the facts underlying the decision?

- Rationality: Was the reasoning process leading to the decision, and the content of the decision itself, markedly unreasonable given the circumstances at the time?

If the decision-making process was rational and based on reasonably gathered information, courts will typically defer to the directors' judgment, even if alternative courses of action might have seemed plausible or ultimately proven more successful. A key Supreme Court decision (Supreme Court, July 15, 2010) affirmed that director decisions do not breach the duty of care unless the decision-making process or content has markedly unreasonable points.

Rationale:

The BJR encourages directors to undertake necessary business risks and pursue innovation without being paralyzed by the fear of personal liability for decisions made honestly and diligently. It acknowledges that directors, not courts, are best positioned to make complex business judgments.

Recent Nuances:

While the core principle remains strong, legal commentators note that its application can evolve. For instance, some discussion arose following a Tokyo District Court ruling on July 13, 2022, concerning director liability at a major electric power company following a nuclear accident. While interpretations vary, some observers suggested this ruling might indicate a stricter review if directors disregard warnings or assessments from internal or external experts without reasonable justification, potentially narrowing the BJR's protective scope in such specific circumstances compared to situations involving pure business forecasts or strategic choices.

The Principle of Trust (信頼の原則 - Shinrai no Gensoku): Delegation in Large Organizations

Modern corporations, especially large ones, operate through complex organizational structures with specialized departments and delegated authority. It is impractical, if not impossible, for top-level directors to personally oversee every operational detail or verify every piece of information generated within the company.

Recognizing this reality, Japanese courts apply the "Principle of Trust" (or "Right to Rely"). This principle allows directors, particularly those in upper management or non-executive roles within large, departmentalized organizations, to reasonably rely on information, reports, and analyses provided by subordinate departments, internal committees, or employees with specific expertise.

Core Principles:

A director's reliance on information from subordinates is generally considered reasonable, and decisions based on that information are protected, provided that:

- The company has a structured division of labor and delegation of authority.

- The director does not have specific knowledge or "red flags" (special circumstances - 特段の事情 tokudan no jijō) that would reasonably cause them to doubt the reliability of the information or the competence of the subordinates providing it.

The assessment considers the director's specific position, duties, knowledge, experience, and the nature of their involvement in the matter at hand. If no such red flags exist, a director trusting the established internal processes and the work of specialized departments fulfills their duty of care regarding the information basis of their decision.

Rationale:

This principle enables efficient management in large organizations by allowing senior management and boards to focus on strategic oversight rather than micromanagement. It acknowledges the necessity of delegation and specialization in complex corporate structures.

Application in Practice: The Osaka District Court Decision (May 20, 2022)

A significant case illustrating the application of both the BJR and the Principle of Trust involved a shareholder derivative suit against former top executives of a major Japanese house building corporation.

Background:

The company suffered substantial losses (over JPY 5.5 billion) resulting from a fraudulent land transaction where it paid a large sum for property based on forged documents, believing it was acquiring land from the rightful owner via an intermediary. Shareholders subsequently filed a derivative lawsuit against the former Representative Director (CEO) and the former Director responsible for the accounting and finance division, alleging breaches of their duties of care and loyalty in approving and executing the transaction.

The Court's Findings (Osaka District Court, May 20, 2022):

The Osaka District Court dismissed the shareholders' claims, explicitly relying on both the BJR and the Principle of Trust.

- Applying the BJR: The court reiterated the standard that director liability arises only if the fact-finding process was flawed or the decision-making process and content were markedly unreasonable.

- Applying the Principle of Trust: The court emphasized that in large companies with established divisions of labor and delegated authority, directors can reasonably rely on the examinations and reports conducted by relevant departments, unless special circumstances warrant skepticism.

- Analysis of the Facts:

- The court noted the company's vast scale (trillion-yen revenues, over 10,000 employees) and its established organizational structure with clear departmental responsibilities and internal approval processes.

- The Representative Director's role was defined as overall business management and strategic decision-making, not detailed vetting of individual real estate contracts below very high financial thresholds (the threshold requiring his approval was JPY 1 billion, whereas this deal, while large, was within the scope requiring lower-level approvals first).

- The court found no specific circumstances that should have alerted the top executives to the sophisticated fraud being perpetrated or caused them to doubt the due diligence performed by the relevant real estate and legal departments.

- Therefore, the directors' reliance on the internal processes and the information provided by subordinates was deemed reasonable. Their decision to proceed with the transaction, based on the information available to them at that time and the internal recommendations, was not considered markedly unreasonable, despite the disastrous outcome.

This judgment underscores that even when substantial losses occur, directors who follow established procedures, reasonably rely on delegated functions within a large organization, and whose decision-making process isn't fundamentally flawed are likely to be protected by these doctrines.

Implications for U.S. Directors and Companies

For U.S. corporations with Japanese subsidiaries, U.S. executives serving as directors of those subsidiaries, or individuals serving on the boards of Japanese partner companies, these doctrines have significant implications:

- Understanding the Standard of Care: While the principles are conceptually similar to U.S. doctrines, their specific application and interpretation by Japanese courts matter. The focus on the decision-making process is paramount.

- Importance of Internal Controls and Delegation: The Principle of Trust highlights the critical importance of having well-defined internal processes, clear delegation of authority, reliable reporting lines, and competent personnel within Japanese operations. The existence and proper functioning of these systems can provide a crucial defense for overseeing directors.

- Documentation is Key: Demonstrating that decisions were made based on adequate information, reasonable analysis, and proper internal procedures is vital. Board minutes and supporting documentation should reflect this process.

- Red Flags Matter: Directors cannot blindly rely on subordinates. If warning signs or inconsistencies emerge ("special circumstances"), directors have a duty to inquire further. Ignoring obvious red flags can negate the protection of the Principle of Trust.

- Comparison with U.S. BJR: While analogous, the formulation and judicial tests might differ subtly. The Japanese BJR's emphasis on whether the process or content was "markedly unreasonable" (ichijirushiku fugeōri) sets the threshold. U.S. directors should not assume identical application but recognize the underlying shared goal of protecting informed, good-faith business decisions.

- Derivative Suit Risk: Shareholder derivative suits are a feature of the Japanese corporate landscape. Understanding these protective doctrines helps directors assess and mitigate liability risks.

Conclusion

The Business Judgment Rule and the Principle of Trust are essential components of Japanese corporate law that shape the landscape of director liability. They represent a balance struck by the courts: holding directors accountable for negligence or disloyalty, while simultaneously protecting those who make informed, good-faith decisions within complex organizational structures. The Osaka District Court's May 20, 2022 decision serves as a potent reminder that in large, departmentalized companies, adherence to rational decision-making processes and justifiable reliance on established internal functions are key factors in shielding directors from liability, even in the face of significant financial setbacks. For U.S. business people and legal professionals involved with Japanese corporate entities, appreciating these doctrines is fundamental to effective governance and risk management.

- Director Liability in Japan: A Case Study Involving Attorney Directors and M&A

- Holding Directors Accountable in Japan: Understanding the Power of Shareholder Derivative Suits

- Crossing Borders, Sharing Responsibility? Director Liability in Japanese Parent Companies for Overseas Subsidiary Misconduct

- Japan Corporate Governance Code – Financial Services Agency