Director Liability in Japan: Lessons from a Case Involving Lawyer-Directors and M&A Due Diligence

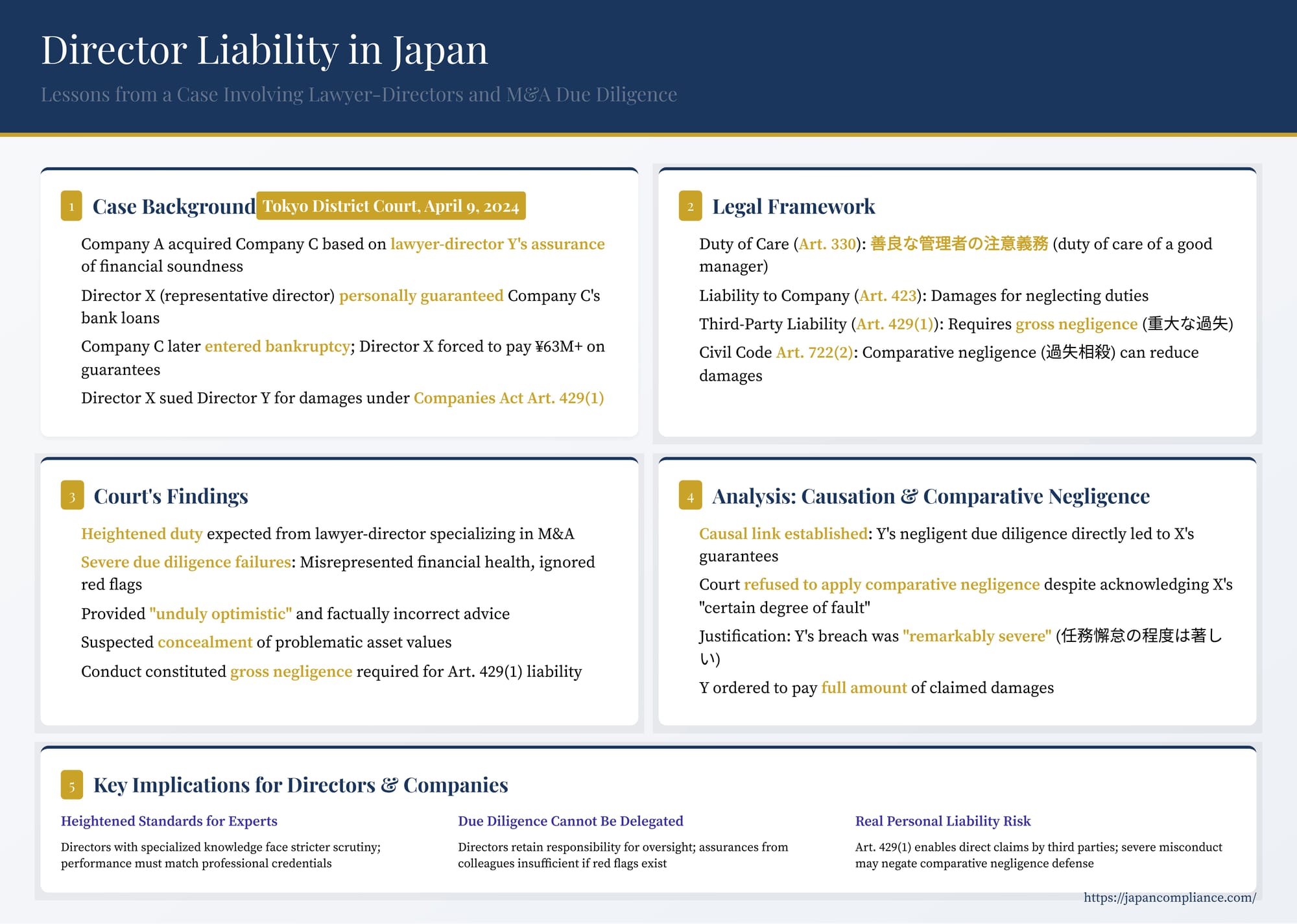

TL;DR: A 2024 district-court ruling voided a board resolution and found a lawyer-director personally liable for grossly negligent M&A due diligence. The case shows that directors with professional expertise carry a higher duty of care and may face full third-party damages when their advice is misleading.

Table of Contents

- Background of the Case: An M&A Deal Gone Wrong

- Legal Framework: Director Duties and Liabilities in Japan

- The Court's Findings: Gross Negligence by the Lawyer-Director

- Linking Director's Breach to Third-Party Harm

- The Decisive Issue: Refusal to Apply Comparative Negligence

- Implications for Directors and Companies in Japan

- Conclusion: Accountability and the Role of Expertise

Corporate governance in Japan continues to evolve, with increasing scrutiny placed on the duties and responsibilities of directors. A recent court decision sheds light on the potential liabilities directors face, particularly those bringing specialized expertise to the boardroom, not just to the company itself but also to third parties who suffer losses due to directorial failures. The Tokyo District Court ruling of April 9, 2024 (Reiwa 6.4.9) provides critical insights into the heightened duty of care expected of professional directors, the consequences of inadequate due diligence in M&A transactions, and the application of comparative negligence in third-party liability claims under Japan's Companies Act.

This case serves as a valuable lesson for companies operating in Japan, especially those relying on directors with legal, financial, or other specialized backgrounds, highlighting the significant personal liability risks involved when duties are neglected.

Background of the Case: An M&A Deal Gone Wrong

The case involved a privately held Japanese company ("Company A") engaged in landscaping and related businesses. Company A decided to acquire another company ("Company C"). This acquisition was primarily handled and advised by one of Company A's directors ("Director Y"), who was a practicing lawyer (bengoshi).

The representative director of Company A ("Director X," who was also the majority shareholder) relied heavily on Director Y's assurances regarding the target company's financial health. Director Y presented Company C as having substantial assets (around 100 million JPY, including significant insurance reserves) and explicitly stated that he, as an M&A specialist lawyer, had conducted thorough due diligence and confirmed the company's financial soundness. Based on these representations, Director X decided to proceed with the acquisition.

A crucial element of the deal involved Director X personally replacing the existing loan guarantees provided by Company C's former representative director ("E") for Company C's debts to banks. Director Y had explained this necessity to Director X, who agreed. Director Y even accompanied and assisted Director X during the process of signing the guarantee agreements at the bank.

Company A acquired all shares of Company C. However, roughly a year later, Company C entered bankruptcy proceedings. As a result, Director X was called upon his personal guarantees and had to make substantial payments to Company C's lenders (over 63 million JPY).

Director X subsequently sued Director Y personally, seeking damages equivalent to the amount he had paid under the guarantees. The claim was primarily based on Article 429, paragraph 1 of the Companies Act, alleging that Director Y, in his capacity as a director of Company A, had breached his duties related to the acquisition, causing harm to Director X (a third party). An alternative claim was made under Article 709 of the Civil Code (tort liability).

Legal Framework: Director Duties and Liabilities in Japan

Understanding the court's decision requires a brief overview of director liability under the Japanese Companies Act (会社法 - Kaishahō).

- Duty of Care (Article 330 Companies Act, Article 644 Civil Code): Directors owe a duty of care of a good manager (善良な管理者の注意義務 - zenryō na kanrisha no chūi gimu, often shortened to 善管注意義務 - zenkan chūi gimu) to the company. This is generally interpreted as the care that an ordinarily prudent person in that position would exercise under similar circumstances.

- Liability to the Company (Article 423): Directors can be held liable to the company for damages caused by neglecting their duties. This often involves proving negligence or breach of the duty of care. The Business Judgment Rule (経営判断の原則 - keiei handan no gensoku) provides some protection for business decisions made in good faith and with reasonable information, but it typically doesn't shield failures in basic due diligence or breaches of loyalty.

- Liability to Third Parties (Article 429(1)): This crucial article states that if officers (including directors) neglect their duties in performing their functions, and they act with knowledge or gross negligence (悪意又は重大な過失 - akui mata wa jūdai na kashitsu), they are liable for damages caused to third parties as a result. This liability extends beyond shareholders to include creditors, counterparties, and, as in this case, potentially other individuals like guarantors who are harmed by the director's grossly negligent conduct in managing the company's affairs.

The Court's Findings: Gross Negligence by the Lawyer-Director

The Tokyo District Court found Director Y liable to Director X under Article 429(1), concluding that he had acted with gross negligence in performing his directorial duties concerning the acquisition of Company C.

1. Heightened Duty of Care: The court explicitly stated that because Director Y was a lawyer and held himself out as an M&A specialist, a higher standard of care was expected of him compared to a director without such expertise. His professional background was a key reason Company A (and Director X) entrusted him with the acquisition process.

2. Failure in Due Diligence: Despite Director Y's assurances, the court found his due diligence severely lacking. He had presented Company C's financial statements, highlighting assets like insurance reserves (approx. 20 million JPY). However, the court determined that Y had failed to investigate the substance of these figures; the insurance reserves, in particular, were found to be essentially non-existent or unavailable. Y had overlooked critical financial red flags, including Company C's ongoing operating losses and negative equity situation.

3. Misleading Advice and Lack of Information: The court found that Director Y's explanations to Director X and the board were "unduly optimistic" and, in some instances, factually incorrect. He failed to point out inconsistencies or concerning aspects in Company C's financial documents. Furthermore, the court strongly suspected (though not definitively proven in this judgment) that Y was aware that the insurance reserves were insubstantial but deliberately failed to report this crucial information to Director X. This failure to provide necessary information and appropriate advice was deemed a significant breach of duty.

4. Gross Negligence: Considering the multiple failures in due diligence, the provision of misleading information, the failure to disclose negative facts, and particularly the heightened standard of care expected of Y as a lawyer-director, the court concluded that his negligence was not merely simple negligence but constituted "gross negligence" (jūdai na kashitsu) as required for liability under Article 429(1).

Linking Director's Breach to Third-Party Harm

A key aspect of Article 429(1) liability is establishing the causal link between the director's neglect of duty (primarily owed to the company) and the damages suffered by the third party.

In this case, Director X's loss arose directly from his personal guarantee of Company C's debts. The court reasoned that Director Y's gross negligence in handling the acquisition for Company A – specifically, his failure to conduct proper due diligence and provide accurate information about Company C's dire financial state – directly led to Director X taking on the guarantee under false pretenses. The decision to acquire Company C and the associated requirement for Director X to provide guarantees were based on Director Y's flawed advice and assurances. Therefore, the court connected Y's grossly negligent performance of his duties as a director of Company A to the personal financial harm suffered by Director X when the guaranteed debts materialized due to Company C's bankruptcy. The duty to provide accurate information necessary for sound decision-making extended implicitly to protecting the interests of the individual (X) who was required to undertake significant personal risk as an integral part of the transaction Y was championing.

The Decisive Issue: Refusal to Apply Comparative Negligence

Perhaps the most legally significant aspect of the ruling was the court's handling of the defense of comparative negligence (過失相殺 - kashitsu sōsai). Director Y argued that Director X, as the representative director of Company A, was also negligent in blindly trusting Y's advice and failing to conduct his own independent assessment before approving the acquisition and taking on the guarantees.

Japanese law allows for the reduction of damages in tort cases if the injured party also contributed negligently to their own loss (Article 722(2) of the Civil Code). This principle is generally applied by analogy to third-party liability claims against directors under Article 429(1) of the Companies Act. If applicable, Director X's damages could have been reduced based on his perceived negligence.

However, the court refused to apply comparative negligence in this instance, ordering Director Y to pay the full amount of damages claimed by Director X.

The court acknowledged that Director X, having received the financial documents and being the ultimate decision-maker as representative director, arguably bore some responsibility ("cannot deny a certain degree of fault"). Nevertheless, it concluded that reducing Y's liability would be inappropriate and unfair (sōtō de wa nai) given the egregious nature of Y's conduct. The court highlighted several factors justifying this refusal:

- Severity of Y's Breach: Director Y's conduct went beyond simple error. His advice was overly optimistic or factually wrong, essentially misleading Director X into a poor decision.

- Failure to Investigate/Disclose: Despite red flags in Company C's financials, Y failed to investigate properly and did not mention these concerns.

- Potential Concealment: The strong suspicion that Y knew about the problematic asset value but concealed it from X weighed heavily against Y.

- Reliance based on Expertise: Director Y's position as a lawyer, carrying a heightened duty, was precisely why Director X placed significant trust in him. Breaching that trust, cultivated by professional status, was seen as particularly blameworthy.

The court essentially concluded that Director Y's breach of duty was so "remarkable" (任務懈怠の程度は著しい - ninmu ketai no teido wa ichijirushii) that it overshadowed any potential negligence on Director X's part, making it contrary to fairness to reduce Y's liability.

Implications for Directors and Companies in Japan

This Tokyo District Court decision offers several important takeaways for US companies with operations or subsidiaries in Japan, their directors (especially expatriates or those with professional backgrounds), and legal advisors:

- Heightened Duty for Expert Directors: Directors possessing specialized knowledge (legal, financial, technical, etc.) are held to a higher standard of care under Japanese law when matters fall within their expertise. Relying on professional titles is not enough; performance must meet that elevated standard. Failure to do so, especially leading to corporate damage, significantly increases liability risk.

- Due Diligence Cannot Be Delegated Away: While boards rely on management and advisors, directors retain ultimate responsibility for oversight, particularly in critical transactions like M&A. This case underscores that due diligence must be substantive and objective. Simply relying on assurances, even from a fellow director with expertise, is insufficient if red flags are missed or ignored. Processes must ensure critical verification occurs.

- Personal Liability to Third Parties is Real: Article 429(1) is a potent tool. Directors whose gross negligence in company management causes financial harm to third parties – creditors, transaction partners, or even fellow directors acting in personal capacities (like guarantors) – face direct personal liability.

- Limits of Comparative Negligence: While comparative negligence is a possible defense in Article 429(1) cases, this ruling demonstrates courts may refuse to apply it where the defendant director's misconduct is particularly severe or involves a breach of trust related to their expertise. Egregious failure can negate the defense, even if the plaintiff might share some blame.

- Importance of Information Flow: Directors have a duty not only to investigate but also to ensure crucial information, especially negative findings from due diligence, is accurately and fully communicated to relevant decision-makers (the board, representative director, individuals undertaking related risks like guarantees). Concealment or overly optimistic framing can be fatal.

Conclusion: Accountability and the Role of Expertise

The Tokyo District Court's ruling in this case reinforces the principle of director accountability in Japan. It sends a clear message that directors, especially those leveraging professional expertise within their board roles, must exercise a high degree of diligence and provide candid, accurate advice. Failure to do so, particularly amounting to gross negligence, can expose them to significant personal liability not only to the company but also to third parties foreseeably harmed by their actions.

The court's refusal to apply comparative negligence, despite acknowledging potential fault by the plaintiff, underscores that fairness considerations can override mechanistic application of the doctrine when a director's breach of duty and trust is profound. For US companies and their directors involved in the Japanese market, this case highlights the critical need for robust governance practices, meticulous due diligence, transparent communication, and a clear understanding of the heightened responsibilities that come with specialized roles on a Japanese board.

- Share-Transfer Restrictions in Closely-Held Japanese Corporations

- Commitment Procedures in Japanese Antitrust

- Derivative vs. Original Acquisition of Rights in Japan

- Ministry of Justice — Guide to Director Liability & Article 429 (JP)

https://www.moj.go.jp/MINJI/minji07_00160.html