Director Liability in Japan: A Case Study Involving Attorney Directors and M&A

TL;DR

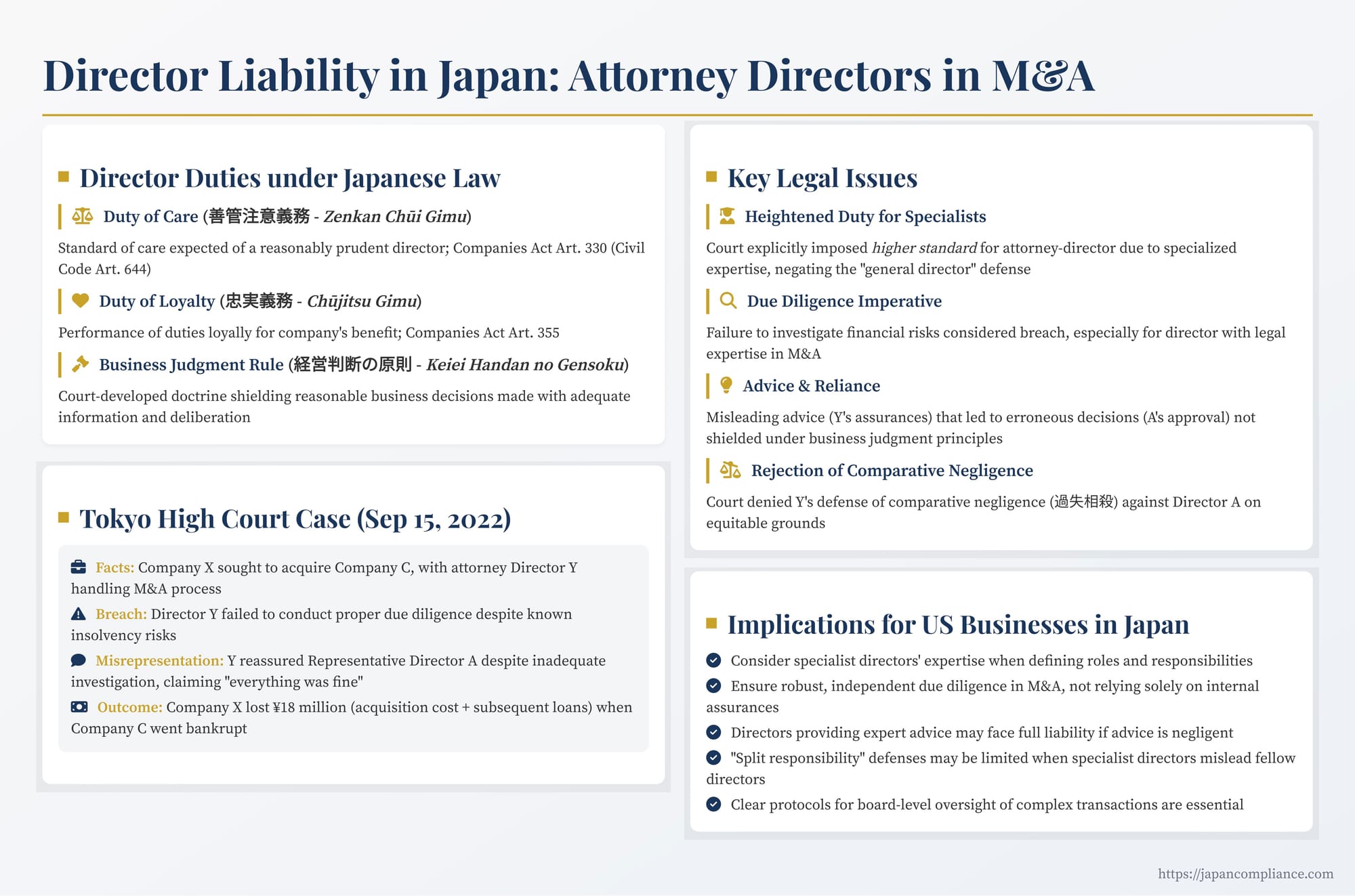

• Tokyo High Court (Sept 15 2022) held an attorney-director personally liable for losses from a failed acquisition because of a heightened duty of care and deficient due-diligence.

• The ruling clarifies that specialist directors cannot rely on the Business-Judgment defence when their expert advice misleads the board.

• Comparative-negligence arguments were rejected, signalling limited scope for offsetting another director’s fault in Japanese internal liability suits.

• US companies should treat due-diligence as non-negotiable, document expert input rigorously, and define board roles clearly when appointing specialist directors.

Table of Contents

- Director Duties under Japanese Law: An Overview

- The Tokyo High Court Case (September 15 2022)

- Key Legal Issues and Analysis

- Implications for US Businesses Operating in Japan

- Conclusion

Understanding the scope and nuances of director liability is crucial for any company operating internationally. In Japan, the duties and potential liabilities of directors, particularly those with specialized expertise like attorneys, present unique considerations, especially in the context of complex transactions such as Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A). A notable decision by the Tokyo High Court on September 15, 2022 (Reiwa 4 (Ne) No. 2012), sheds light on these issues, specifically addressing the heightened duty of care for attorney-directors and the limited applicability of comparative negligence defenses in breach of duty claims brought by the company.

Director Duties under Japanese Law: An Overview

Before delving into the specifics of the case, it's helpful to understand the foundational duties of directors under Japan's Companies Act (Kaisha Hō).

- Duty of Care (善管注意義務 - Zenkan Chūi Gimu): Article 330 of the Companies Act stipulates that the relationship between a company and its directors is governed by the provisions on mandates (agency). This incorporates Article 644 of the Civil Code, which requires a mandatary (agent/director) to manage the entrusted affairs with the "care of a good manager." This is generally interpreted as the duty of care expected of a reasonably prudent person in a similar position, considering the specific circumstances and the director's role and abilities. It encompasses monitoring fellow directors and ensuring the company's operations are lawful and appropriate.

- Duty of Loyalty (忠実義務 - Chūjitsu Gimu): Article 355 imposes a duty on directors to comply with laws, regulations, the articles of incorporation, and shareholders' meeting resolutions, and to perform their duties loyally for the benefit of the company. This duty prevents directors from prioritizing their own interests or those of third parties over the company's interests.

- Business Judgment Rule (経営判断の原則 - Keiei Handan no Gensoku): While not explicitly codified in the Companies Act like in some US jurisdictions (e.g., Delaware), Japanese courts have developed a doctrine analogous to the Business Judgment Rule. This principle generally shields directors from liability for business decisions that turn out poorly, provided the decision-making process was reasonable and based on adequate information gathering and deliberation, without conflicts of interest or gross negligence. However, it does not excuse a fundamental failure to exercise due care or loyalty.

The Tokyo High Court Case (September 15, 2022)

This case involved a dispute between a holding company (Company X) and one of its directors (Director Y), who was also a licensed attorney (Bengoshi).

The Facts:

- Company X, a holding company primarily involved in acquiring and managing real estate-related businesses, sought to acquire another entity, Company C.

- Company X's Representative Director (Director A) entrusted Director Y, an attorney serving on Company X's board, with handling the M&A process for acquiring Company C. An M&A advisor had initially proposed the deal.

- During the preliminary stages, Director A faced difficulties securing bank financing for the acquisition because Company C was reportedly insolvent. Director A initially considered abandoning the deal but decided to proceed, partly to avoid potential disputes related to backing out.

- Director Y continued negotiations and obtained certain financial documents from Company C, including monthly profit and loss statements.

- At a board meeting on June 26, 2018, Director A questioned Director Y about the viability of the acquisition. Director Y reassured Director A, presenting Company C's tax returns and stating that Company C possessed sufficient assets (around 100 million yen) to cover its debts, making the acquisition financially sound. Crucially, Director Y emphasized that Y, as an M&A specialist attorney, had conducted due diligence and everything was fine.

- Based on Director Y's assurances, Director A approved the acquisition. In July 2018, Company X acquired all shares of Company C for 10 million yen. Company X financed this purchase through a loan from Director A.

- Following the acquisition, Company X tasked Director Y with overseeing the management of Company C as part of Y's directorial duties for Company X.

- Between August and November 2018, Director Y informed Director A that Company C required capital infusions to avoid bankruptcy. Director A lent an additional 8 million yen to Company X, which Company X then lent to Company C.

- Despite these efforts, Company C entered bankruptcy proceedings in July 2019, which were eventually discontinued due to lack of assets (異時廃止 - ijihai shi).

- Company X sued Director Y, alleging breach of the duty of care (Zenkan Chūi Gimu) under Article 423, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act. Company X sought damages totaling 18 million yen, representing the acquisition cost and the subsequent loan amount.

Lower Court and Appeal:

- The Tokyo District Court found Director Y fully liable for the 18 million yen in damages, agreeing that Y had breached the duty of care.

- Director Y appealed to the Tokyo High Court. In the appeal, Y introduced a new argument: comparative negligence (過失相殺 - Kashitsu Sōsai). Y argued that Director A, as the Representative Director who made the final decision to acquire Company C without conducting independent investigations or ordering Y to do so more thoroughly, shared responsibility for the loss.

Tokyo High Court Decision and Reasoning:

The High Court upheld the District Court's decision, dismissing Director Y's appeal. The court's reasoning centered on several key points:

- Duty of Care Affirmed: The court reiterated that Director Y, as an executive director of Company X responsible for the acquisition, owed a duty of care. This duty included avoiding the acquisition if it presented a foreseeable risk of causing irrecoverable or near-irrecoverable losses to Company X.

- Heightened Duty for Attorney-Director: The court explicitly stated that Director Y's duty of care was heightened because Y possessed the qualifications of an attorney and was appointed to the board on that premise. This specialized knowledge meant a higher standard of diligence was expected.

- Foreseeable Risk and Breach: The court found that acquiring Company C objectively carried a high risk of substantial loss for Company X, given C's financial state. Furthermore, Director Y had access to documents (recent financial statements) revealing these risks before the acquisition. Therefore, Y could and should have recognized the danger.

- Failure in Due Diligence: Given the identified risks, the court determined that Director Y, as part of the duty of care, had an obligation to conduct a reasonably thorough investigation (due diligence) into the substance behind the figures in Company C's financial statements. The court found that Director Y failed to conduct such an investigation. This failure constituted a breach of duty (任務懈怠 - ninmu ketai).

- Misleading Advice Nullified "Management Decision" Defense: The court addressed Director Y's argument that Director A made the ultimate "management decision" (経営判断 - keiei handan). While acknowledging A's final authority, the court emphasized that Director A was deprived of appropriate information and advice needed to make a sound judgment. Instead, Director Y provided information and advice that led A to make an erroneous decision. Consequently, A's decision did not absolve Y of liability stemming from Y's own breach of duty.

- Liability for Subsequent Loan: The court applied similar reasoning to the 8 million yen loan made post-acquisition, finding Director Y liable for this loss as well, stemming from the initial flawed acquisition and subsequent mismanagement or failure to properly advise against further investment.

- Rejection of Comparative Negligence: The court rejected Director Y's argument for comparative negligence (Kashitsu Sōsai) against Director A. It reasoned that, considering the overall circumstances – particularly that Y was an attorney-director whose inappropriate advice led A to make flawed decisions regarding both the acquisition and the loan – it would be contrary to principles of equity (衡平上相当とはいえない - kōhei jō sōtō to wa ienai) to reduce Y's liability by attributing fault to A.

Key Legal Issues and Analysis

This judgment brings several critical aspects of Japanese director liability into focus:

1. Heightened Duty of Care for Specialist Directors:

A standout feature of this case is the court's explicit recognition of a heightened duty of care for a director possessing specialized qualifications, specifically legal expertise relevant to the task (M&A). While the general standard is that of a "good manager," this case confirms that when a director is appointed or relied upon for specific professional skills, their conduct will be evaluated against a standard informed by that expertise. This aligns with the principle that the duty of care is relative to the director's position and capabilities. US corporate law similarly considers a director's specific expertise as part of the context when evaluating whether they acted with due care, although the explicit "heightening" might be articulated differently. The key is that directors cannot hide behind a veil of general business knowledge when their specific professional skills are germane to the matter at hand.

2. The Imperative of Due Diligence:

The ruling underscores the fundamental importance of adequate due diligence, particularly in M&A. Director Y's assurances, even bolstered by Y's status as an attorney, were insufficient to meet the duty of care. The court expected a proactive investigation into the financial health of the target company, especially given known red flags like insolvency. Merely reviewing provided documents without critical examination or further inquiry was deemed inadequate. This serves as a reminder that due diligence is not a passive exercise but requires active verification and analysis.

3. Advice, Reliance, and the Limits of the Business Judgment Defense:

The court's handling of the interplay between Director Y's advice and Director A's decision is significant. It illustrates that the protection afforded by the business judgment principle (Keiei Handan no Gensoku) to the decision-maker (A) does not necessarily shield the advising director (Y) if the advice itself was rendered negligently or in breach of duty. Y's failure to provide accurate information and sound advice directly tainted A's decision-making process. This highlights that directors providing specialized advice, particularly in M&A, carry substantial responsibility for its quality and accuracy. Their breach can lead to liability even if the final "go/no-go" decision rests with another director or the board as a whole.

4. Comparative Negligence (Kashitsu Sōsai) in Director Liability Suits:

Perhaps the most complex issue is the rejection of the comparative negligence defense. Kashitsu Sōsai is a concept allowing for the reduction of damages based on the plaintiff's own negligence contributing to the loss. In the context of a company (Plaintiff X) suing its director (Defendant Y), applying this doctrine would mean reducing the company's recovery due to the negligence of another agent of the company (Director A).

The High Court did not state that comparative negligence is never applicable in director liability cases against the company. Indeed, other cases, such as a Yokohama District Court decision from July 31, 1998 (Hanrei Times 1014-253), have applied it, reducing a representative director's liability by 20% due to negligence by the company's substantial owner who directed the representative director.

However, in this specific case, the Tokyo High Court found its application inequitable. The commentary surrounding the case suggests several potential factors influencing this "equity" consideration:

- Director Y's Expertise: As an attorney specifically relied upon for M&A advice, Y's breach was seen as particularly significant.

- Director A's Reliance: A reasonably relied on the specialist advice provided by Y.

- Source of Funds: The funds lost ultimately originated from Director A (loaned to Company X). Holding Y fully liable might have been seen as a way to more directly compensate the ultimate source of the funds, who was misled by Y. A might have been the owner-shareholder, closely aligning A's interests with the company's loss.

The court's precise reasoning for invoking "equity" remains somewhat opaque. It could mean that comparative negligence was simply inappropriate on these specific facts, or it could carry a broader implication that in cases of specialist directors providing misleading advice, equity generally weighs against reducing their liability based on the actions of the relying non-specialist directors. This differs from typical US corporate litigation where contribution claims between directors might be possible, but a comparative negligence defense against the company based on the actions of one of its directors in a suit against another director is less common.

Implications for US Businesses Operating in Japan

The principles highlighted in this Tokyo High Court decision offer several practical takeaways for US companies with Japanese operations or engaging in M&A in Japan:

- Director Selection and Roles: Carefully consider the expertise required for board positions. If appointing specialists (lawyers, accountants, industry experts), understand they may be held to a standard reflecting that expertise. Clearly define roles and responsibilities, especially for complex transactions.

- Due Diligence is Non-Negotiable: Robust, independent due diligence is critical in M&A. Do not rely solely on assurances, even from directors with relevant professional backgrounds. Ensure processes involve critical assessment and verification.

- Accountability for Advice: Directors providing specific advice, particularly expert advice, can be held liable if that advice is negligent and leads to flawed decisions by others, even those with final authority (like a Representative Director or the Board).

- Understanding Liability Exposure: A director's breach can lead to full liability for resulting losses, even if other directors were involved in the final decision-making process, especially if the breach involved providing misleading information.

- Limited Defenses: Be aware that defenses common in other contexts, like comparative negligence, may face limitations in director liability suits brought by the company in Japan, depending on the specific facts and equitable considerations determined by the court.

Conclusion

The Tokyo High Court's decision reinforces the seriousness with which Japanese courts approach the duty of care owed by directors, particularly those leveraged for their specialized skills in critical transactions like M&A. It emphasizes that reliance on professional status is no substitute for diligent investigation and accurate advice. While the business judgment principle offers protection for reasonable decisions, it does not shield directors whose breaches of duty—including providing misleading expert counsel—lead the company into foreseeable harm. Furthermore, the case signals that courts may take a nuanced, equity-based approach to defenses like comparative negligence, potentially holding specialist directors fully accountable when their failings mislead fellow directors and harm the company. For foreign businesses, this underscores the need for meticulous director selection, clearly defined roles, rigorous transaction processes, and a thorough understanding of the accountability framework within Japanese corporate law.

- Board Discretion and Director Accountability in Japan: Insights from a 2024 Supreme Court Ruling

- Japan M&A Guide 2025: Legal Essentials & Practical Tips for U.S. Companies

- Parent Company Director Liability in Japan: Oversight of Subsidiary Compliance Failures

- Japanese Law Translation — Ministry of Justice