Digitalizing Japan’s Civil Litigation: E-Filing, E-Service & Business Impact

TL;DR: Japan’s civil-procedure overhaul mandates e-filing for lawyers, introduces system-based e-service, and gives parties online access to case files. Businesses must upgrade IT workflows, evidence management, and litigation strategy before full rollout by 2026.

Table of Contents

- The Foundation: Mandatory E-Filing for Legal Professionals

- Transforming Service of Process: E-Service via the Court System

- The Electronic Case Record: Access and Management

- Handling Evidence in the Digital Age

- Facilitating Remote Proceedings

- Implications for Businesses and Litigation Strategy

- Conclusion: Towards a Modernized Civil Justice System

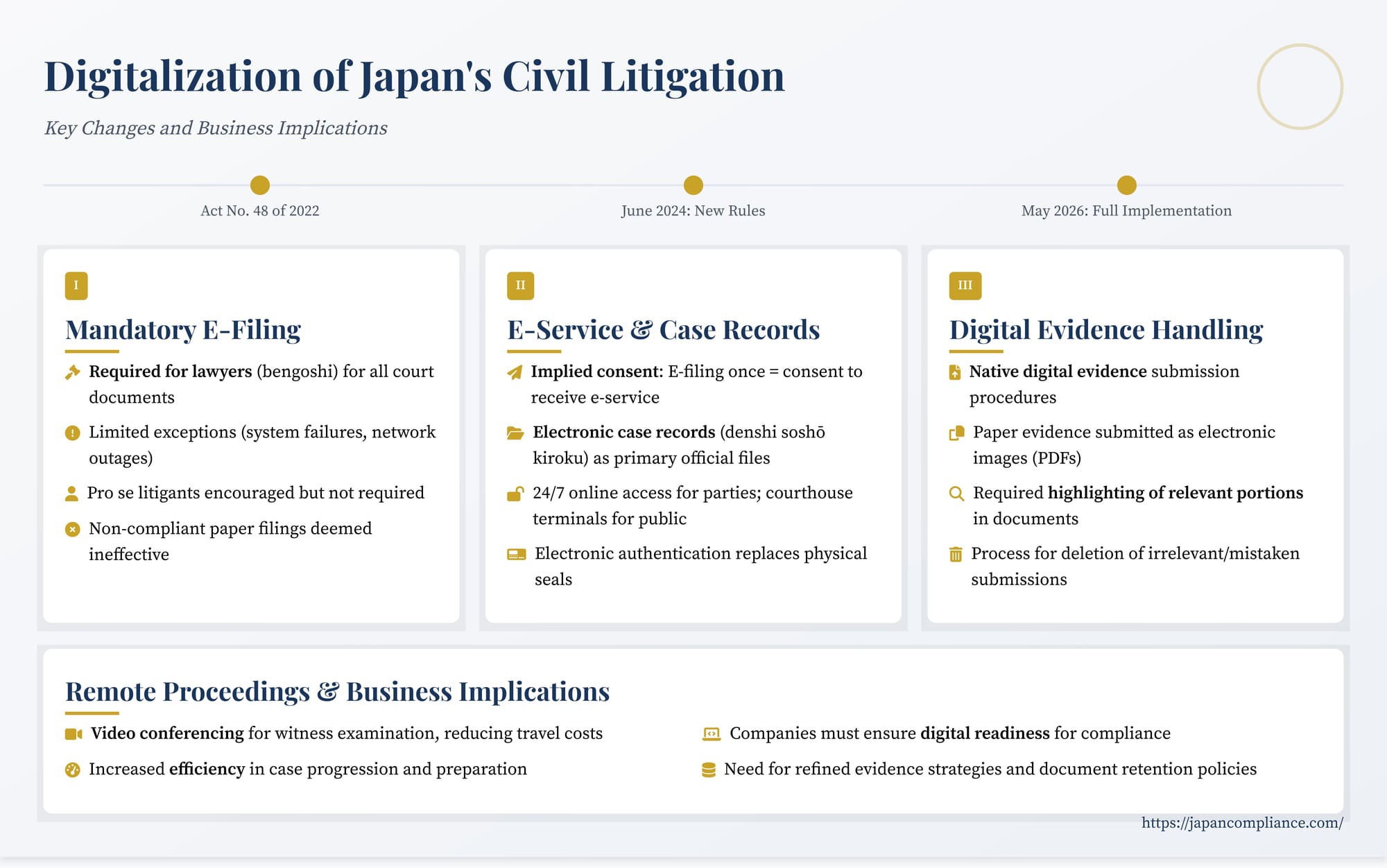

Japan's civil justice system is undergoing its most significant transformation in decades with the comprehensive digitalization of its court procedures. Driven by amendments to the Code of Civil Procedure enacted in 2022 (Act No. 48 of 2022) and detailed in the new Rules of Civil Procedure promulgated in June 2024 (Supreme Court Rule No. 14 of 2024), these changes are set to be fully implemented by May 2026. The reforms aim to modernize litigation by leveraging information technology to enhance efficiency, speed up proceedings, reduce costs, and improve access to justice.

For businesses involved in or potentially facing litigation in Japan, understanding these fundamental shifts – from mandatory electronic filing for represented parties to online access to case records and new methods for handling digital evidence – is crucial for effective case management and strategic planning.

The Foundation: Mandatory E-Filing for Legal Professionals

The cornerstone of the reform is the transition to a court-operated electronic filing (e-filing) system, moving away from the traditional paper-based paradigm.

- Obligation for Lawyers: A pivotal change is the mandatory requirement for lawyers (bengoshi), as well as other designated legal representatives acting under mandate (like patent agents in relevant IP cases), to submit nearly all court documents electronically via the new system. This includes not only foundational documents like complaints (sojō) and briefs (junbishomen), but also formal motions (mōshitate tō) and even supporting materials such as proof of corporate registration or power of attorney (New Rules of Civil Procedure [hereinafter "New Rule(s)"] 52-9 ff., 14(3), 23(3), etc.). The rationale is that legal professionals possess the necessary technical capacity and are expected to lead the drive towards greater procedural efficiency.

- Narrow Exceptions: The obligation is strict. Filing via paper by a represented party is permissible only in limited circumstances, such as verifiable court system failures or major communication network outages beyond the filer's control (New Code of Civil Procedure [hereinafter "New Code"] Art. 132-11(3); New Rule 52-14). Filing paper documents without such justification renders the filing legally ineffective.

- Encouragement for Unrepresented Parties: While individuals or companies representing themselves (pro se) are not legally mandated to e-file if they lack the necessary IT equipment or skills, the rules strongly encourage its use (New Rule 52-12). The long-term goal is clearly towards universal e-filing. Support mechanisms are envisioned to assist those unfamiliar with the technology (New Rule 52-11(1) proviso), potentially involving designated helpers like judicial scriveners (shihō shoshi).

- Impact: This mandatory shift necessitates that law firms and legal departments handling Japanese litigation are fully equipped with the necessary hardware, software, and trained personnel for digital submissions. It promises to reduce paper handling, postage costs, and potentially accelerate filing times.

Transforming Service of Process: E-Service via the Court System

Complementing e-filing is the introduction of electronic service of process (denshi sōtatsu) through the court's official system (New Code Art. 109-2 ff.).

- Implied Consent Rule: A crucial aspect is that any party (represented or not) who utilizes the e-filing system for any submission is thereby required to consent to receive subsequent service of documents electronically via that same system (New Rule 52-9(4)). Parties must file a formal notification of consent (shisutemu sōtatsu no todokede) when they first e-file. This prevents parties from cherry-picking – using the convenience of e-filing for submissions while insisting on traditional paper service for documents served upon them.

- Post-Initiation Service: Once parties are registered for system service, subsequent documents from the court or opposing parties can be served electronically through the system, with notifications likely sent via email (New Rule 45-2 ff.). This promises significantly faster and more reliable service compared to traditional mail or courier methods, reducing procedural delays.

- Initial Service of Complaint: Serving the initial complaint (sojō) on the defendant remains a practical challenge. While system service is possible if the defendant has already consented (e.g., a large corporation proactively registering), the rules anticipate that in many cases, the plaintiff will still need to provide the court with physical copies (printed from the e-filed complaint) for traditional service methods initially (New Rule 58). However, to facilitate early e-service, a new rule requires plaintiff's counsel, when filing the complaint, to notify the court if they know who represented the defendant during pre-litigation negotiations. This allows the court potentially to contact the defendant's likely counsel and encourage them to register for system service promptly, enabling electronic service of the complaint itself (New Rule 55-2).

The Electronic Case Record: Access and Management

The reforms envision a shift from paper-based court files to electronic case records (denshi soshō kiroku) as the primary official record.

- Digital Native Documents: Electronically filed documents become part of the record directly. Court-generated documents like judgments (hanketsu), orders (kettei), and records of proceedings (chōsho) will also be created and maintained electronically. Traditional requirements for physical signatures and seals by judges and clerks are being replaced by secure electronic authentication methods (New Rule 66 ff., 155 ff.).

- Online Access for Parties: A major benefit for litigants and their representatives is the ability to access the complete electronic case file securely via the internet, 24/7, using assigned IDs and passwords. This includes the ability to view and download (fukusha, which includes downloading digital copies) case documents (New Rule 33-2). This drastically improves convenience for case review, preparation, and team collaboration compared to inspecting physical files at the courthouse.

- Public Access: Access for the general public (non-parties without a demonstrated legal interest) remains more limited. While the principle of open access to court records is maintained (New Code Art. 91-2(1)), non-parties must still visit the courthouse and use designated terminals to view the electronic record under supervision. They are generally not permitted to download or copy the files electronically (New Rule 33-2(1)i, 33-2(3)).

- Managing Representation: For cases with numerous lawyers representing a single party (more than 10), the rules require designating a core group (up to 10) who will be actively using the system for filing and access to streamline system administration (New Rule 52-13).

Handling Evidence in the Digital Age

The digitalization extends to how evidence is submitted and managed:

- Submitting Digital Evidence: Clear procedures are established for submitting evidence that originates in electronic format (e.g., emails, spreadsheets, databases, digital audio/video). Parties must submit electronic copies of these records via the system, accompanied by an explanatory document (setsumeisho) detailing the evidence's relevance and how it should be examined (New Rule 149-2 ff.; cf. New Code Art. 231-2, 231-3).

- Submitting Paper Evidence Electronically: Copies of traditional paper documents submitted as evidence (shoshō) are filed electronically as image files (e.g., PDFs) (New Rule 137(3)).

- Discouraging Data Dumps: Recognizing that the ease of e-filing might tempt parties to submit excessive amounts of uncurated data, the new rules explicitly encourage discipline. Parties are urged to submit only evidence that is necessary and sufficient to prove their points (New Rule 137(2)i, 149-4).

- Highlighting Relevance: When submitting documents (especially lengthy ones), parties are encouraged to clearly indicate the specific portions relevant to the facts they seek to prove, using methods like electronic highlighting or annotations (New Rule 137(2)ii, 149-4).

- Withdrawing/Deleting Submissions: A potentially useful new mechanism allows parties, with the consent of all other parties and court approval, to request the deletion of electronically filed documents (such as evidence copies or briefs) from the official record, provided those documents have not yet been formally presented or examined in court proceedings (New Rule 33-5). This could help streamline the record by removing superfluous or mistakenly filed materials.

Facilitating Remote Proceedings

The reforms also formally integrate provisions facilitating remote participation in court proceedings, particularly for witness examinations conducted via video conferencing systems (New Rule 123). This allows witnesses, including experts, to testify from locations outside the courthouse, provided certain conditions ensuring procedural fairness and reliability are met. This can significantly reduce travel costs and logistical hurdles, especially for witnesses located far from the court or overseas.

Implications for Businesses and Litigation Strategy

These comprehensive digitalization reforms will have significant practical impacts on how businesses approach and manage civil litigation in Japan:

- Digital Readiness is Essential: Companies involved in Japanese litigation, along with their internal legal teams and external counsel, must ensure they have the necessary IT infrastructure, digital document management capabilities, and training to comply with e-filing requirements and effectively utilize the electronic case management system.

- Potential for Increased Efficiency: E-filing and e-service should reduce delays associated with paper handling and mail, potentially leading to faster overall case progression. Online access to records enhances case preparation efficiency.

- Adapting Evidence Strategies: Businesses need strategies for managing and presenting both natively digital evidence and digitized paper documents effectively within the electronic system. Internal document retention and collection practices should consider the potential need for electronic submission. While formal US-style discovery is absent, the ease of submitting large data volumes electronically may increase pressure for thorough internal investigation and careful evidence selection.

- Cost Adjustments: While costs related to paper, printing, and couriers should decrease, investment in appropriate technology, software licenses, and user training will be necessary.

- Procedural Awareness: Legal teams must adapt to new procedural deadlines, methods of service, and protocols for interacting with the court and accessing records electronically.

Conclusion: Towards a Modernized Civil Justice System

The digitalization of Japan's civil litigation procedures represents a fundamental modernization effort. The transition to mandatory e-filing for professionals, system-based service, fully electronic case records accessible online to parties, and updated rules for digital evidence promises significant gains in efficiency, accessibility, and transparency. While the transition period will require adaptation and investment from all stakeholders – courts, lawyers, and litigants alike – the ultimate goal is a civil justice system better equipped for the digital age. For businesses operating in Japan, understanding and preparing for these changes is not just about compliance; it's about leveraging the new system effectively to manage disputes more efficiently and strategically in the years to come.

- Navigating the Digital Shift: Key Changes to Japan’s Code of Civil Procedure

- Navigating Japan’s New Civil Procedure: The IT Revolution in Japanese Courts

- Navigating Civil Litigation in Japan: A Primer for US Companies (May 2025)

- Supreme Court of Japan — Civil Procedure IT Reform Overview

https://www.courts.go.jp/about/system_itka/index.html