Digital Doubles: AI Avatars, Privacy, and Portrait Rights for Entertainers in Japan

TL;DR

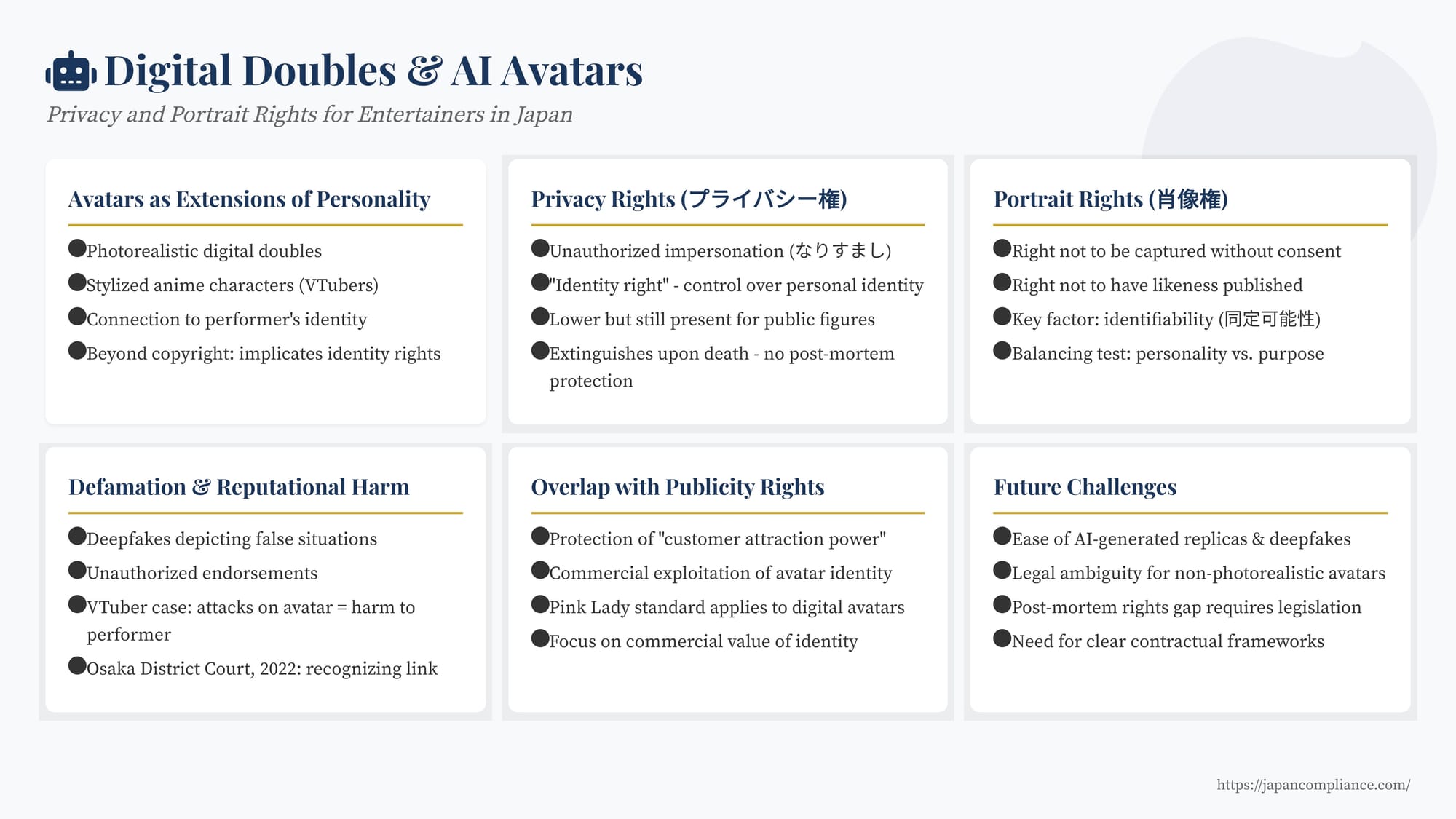

- AI avatars implicate Japanese privacy, portrait and publicity rights when they identify a real entertainer.

- Creating or using photorealistic avatars without consent can breach portrait rights; stylised VTuber avatars may also be protected if strongly tied to a performer.

- Entertainers need explicit contracts, while businesses must secure licences and monitor deep-fake risks.

Table of Contents

- Avatars as Extensions of Personality

- Privacy Rights and AI Avatars

- Portrait Rights (Shōzōken) and AI Avatars

- Defamation and Reputational Harm

- Overlap with Publicity Rights

- Challenges and the Road Ahead

- Conclusion

The line between the real and the virtual continues to blur, particularly in the entertainment industry. From globally famous rock bands performing as digital avatars to the rise of VTubers (Virtual YouTubers) who embody entirely digital personas, AI-generated representations are becoming increasingly common. This trend opens exciting creative avenues but also raises complex legal questions about how an entertainer's identity is protected in the digital realm. In Japan, the key legal frameworks involved are the rights to privacy (プライバシー権, puraibashī-ken) and portrait rights (肖像権, shōzōken).

Avatars as Extensions of Personality

An "AI avatar" in this context can range from a highly realistic, photorealistic digital double of an entertainer to a stylized anime character or even a non-human entity. Regardless of the visual form, when an avatar is used consistently by a specific performer – voiced by them, animated through their motion capture, embodying their personality, sharing their experiences – it can become strongly associated with that individual's identity. This connection is crucial when considering legal protections. While a fictional character per se might primarily be subject to copyright, an avatar consistently representing a real person implicates rights tied to that person's identity and likeness.

Privacy Rights and AI Avatars

Japanese law protects the right to privacy, evolving from the concept of the "right to be left alone" to encompass rights related to controlling personal information ("informational self-determination"). How does this apply to AI avatars?

- Impersonation and Identity: A significant risk is the unauthorized creation or use of an entertainer's AI avatar for impersonation (narisumashi). If a third party uses an avatar convincingly representing a real entertainer to deceive the public or damage their reputation, this could potentially infringe upon what some Japanese legal commentators conceptualize as an "identity right" – the right to maintain control over one's personal identity in relation to others. An Osaka District Court decision in 2016, dealing with online impersonation, acknowledged the potential harm caused when a false persona created by impersonation becomes widely accepted, making it difficult for the actual person to live peacefully. While not yet a formally established standalone right, this concept addresses the core harm of having one's identity hijacked, digitally or otherwise.

- "Public Figure" Doctrine: Entertainers, as public figures, generally have a lower expectation of privacy regarding matters in the public sphere compared to private citizens. However, this does not eliminate their privacy rights entirely. It wouldn't justify, for instance, the misuse of an avatar to fabricate false private information or engage in severe harassment that intrudes upon their personal life beyond legitimate public interest.

- Post-Mortem Limitations: Crucially, privacy rights are considered personal and extinguish upon death in Japan. This means that after an entertainer passes away, their estate or family generally cannot rely on privacy law to prevent the creation or use of an AI avatar based on the deceased, unless perhaps it constitutes defamation of the deceased or severely infringes the family's own feelings of reverence and remembrance (a high bar).

Portrait Rights (Shōzōken) and AI Avatars

Portrait rights (shōzōken) are perhaps more directly relevant to the visual representation inherent in avatars. Rooted in personality rights (jinkaku-ken), shōzōken in Japan encompass two main aspects established by Supreme Court precedent:

- The right not to have one's likeness (face and figure) photographed, filmed, or otherwise captured without consent (established in the Kyoto Prefectural Gakuren case, Supreme Court, December 24, 1969).

- The right not to have one's captured likeness published or publicly disseminated without consent, especially for commercial purposes (related to the Hōtei Irausto Ga ["Courtroom Sketch"] case, Supreme Court, November 10, 2005, concerning publication).

Applying this to AI avatars:

- Photorealistic Avatars: Creating an AI avatar by digitally scanning or meticulously replicating an entertainer's actual appearance without consent could infringe the first aspect of shōzōken. Subsequently using or publishing this unauthorized photorealistic avatar, especially commercially, would likely infringe the second aspect. The key is identifiability (dōtei kanōsei) – whether the avatar is clearly recognizable as the specific entertainer.

- Stylized/Character Avatars (e.g., VTubers): This is where the law is less settled. If an avatar is heavily stylized and doesn't physically resemble the "person inside," does shōzōken apply? Some legal scholarship argues it can. If the avatar functions as the public face of the performer, is uniquely associated with them, and embodies their personality through voice and actions, it could be considered their legally relevant "portrait" for the purpose of their activities, akin to a performer's mask. A 2021 Tokyo District Court decision involving defamation against a VTuber supported this view, finding that attacks targeting the avatar could harm the legally protected interests (specifically,名誉感情 meiyo kanjō - honor sentiment or self-esteem) of the identifiable performer behind it, given the close connection between the avatar's activities and the performer's personality and experiences.

- Infringement Test: Whether the unauthorized creation or use of an avatar infringes shōzōken involves balancing the entertainer's personality interests against various factors, including the purpose, necessity, and manner of the use, and whether it exceeds the bounds of social tolerance (shakai seikatsu jō junin no gendo), drawing from the factors outlined by the Supreme Court in likeness publication cases. Commercial exploitation without consent is highly likely to be deemed infringing.

Defamation and Reputational Harm

Beyond privacy and portrait rights, the misuse of AI avatars poses a significant threat of defamation and reputational harm. Deepfakes depicting entertainers in false or compromising situations, unauthorized endorsements, or avatars used for harassment can severely damage careers built on public image. As mentioned, Japanese courts have begun to recognize that defamatory or insulting statements directed at a VTuber's avatar can constitute unlawful harm to the reputation or personal feelings of the identifiable performer behind it, provided the link is clear (e.g., Osaka District Court, August 31, 2022).

Overlap with Publicity Rights

Where the unauthorized use of an AI avatar primarily aims to capitalize on the entertainer's fame and "customer attraction power," the Right of Publicity becomes central. If an avatar embodying a celebrity's identity is used on merchandise, in advertising, or as the product itself without permission, it likely infringes their publicity rights under the Pink Lady standard (see previous post). This right specifically protects the commercial value of their identity.

Challenges and the Road Ahead

The rapid evolution of AI presents ongoing challenges:

- Ease of Creation/Misuse: AI tools make it increasingly easy for third parties to create convincing digital replicas or deepfakes, potentially for malicious purposes like disinformation or harassment.

- Legal Ambiguity: While existing rights offer some protection, their application to novel forms of digital representation, particularly non-photorealistic but identifying avatars, requires further clarification through case law or legislation.

- Post-Mortem Rights Gap: The lack of clear post-mortem publicity or personality rights in Japan leaves the digital legacies of deceased entertainers vulnerable to unauthorized exploitation. Calls for legislative action to address this gap are likely to intensify.

- Contractual Clarity: For living entertainers, clear agreements with agencies, platforms, and production companies regarding the creation, ownership, control, and permissible uses of their official digital likenesses and AI avatars are becoming increasingly vital. Lessons from recent labor disputes in the US entertainment industry regarding AI highlight the importance of proactively addressing these issues contractually.

Conclusion

AI avatars offer entertainers unprecedented ways to engage with audiences and extend their careers, but they also introduce new vulnerabilities regarding the protection of their identity, likeness, and reputation. While Japan's existing framework of privacy rights, portrait rights, and publicity rights provides a foundation for protection, the unique nature of digital replicas and the speed of technological change necessitate careful legal analysis and, potentially, future legislative adjustments. Ensuring that the law adequately safeguards personal identity and commercial value in the age of AI, while still allowing for creative innovation, will be a key challenge for Japan's legal system in the coming years.

- Protecting Stardom in Japan: Publicity Rights for Stage & Group Names

- Who Owns AI-Generated Works in Japan? Copyright, Authorship & Article 2 Criteria Explained

- False IP Takedowns on Japanese E-Commerce Platforms: UCPA Liability & Risk-Control Guide

- Personal Information Protection Commission – Q&A on Portrait & Privacy Rights (Japanese)

- Agency for Cultural Affairs – Portrait/Publicity Rights FAQ (Japanese)