Dialing in on Depreciation: Japanese Supreme Court Defines 'Asset Unit' for PHS Network Rights in the NTT Docomo Case

Date of Judgment: September 16, 2008

Case Name: Corporate Tax Reassessment Invalidation Lawsuit (平成18年(行ヒ)第234号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

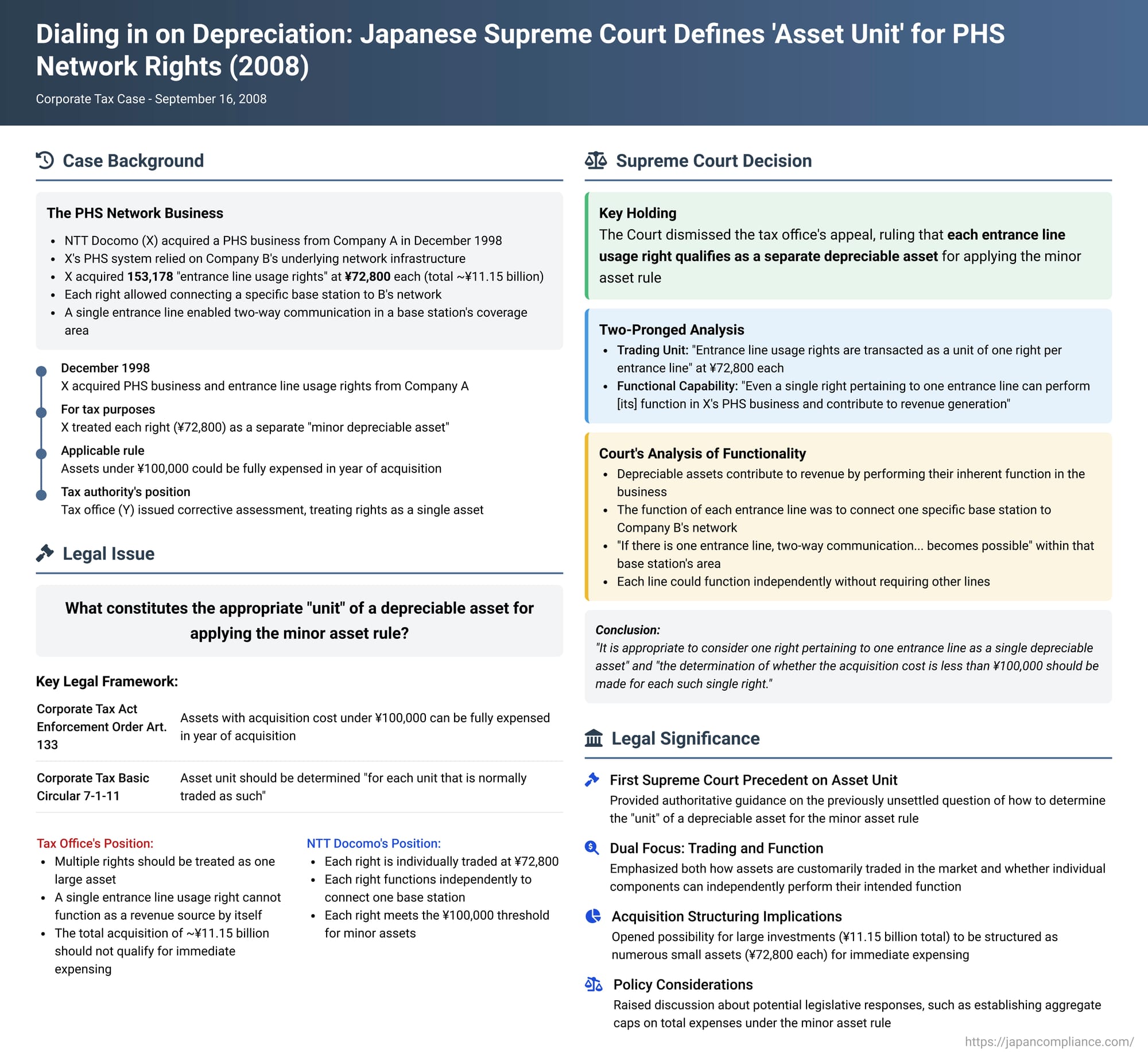

In a significant decision for corporate taxation, commonly known as the NTT Docomo case, the Supreme Court of Japan on September 16, 2008, clarified the criteria for determining the "unit" of a depreciable asset. This determination is crucial for identifying whether an asset qualifies as a "minor depreciable asset," allowing its full acquisition cost to be expensed in the year of acquisition. The case specifically involved "entrance line usage rights" essential for a Personal Handy-phone System (PHS) network, and the Court's ruling provided much-needed guidance on a previously unsettled point of law.

The Technological and Financial Context: PHS Networks and Asset Acquisition

The respondent, X (a major telecommunications company, formerly NTT Docomo), operated various mobile phone services, including a PHS business. On December 1, 1998, X acquired an existing PHS business from another company, A.

X's PHS system was of a type dependent on the network infrastructure of a major underlying carrier, Company B. In this setup, communication between a PHS user's terminal and, for example, a fixed-line telephone, would occur via several components: a PHS base station (installed by X), an "entrance line" (a wired transmission path connecting X's base station to B's PHS connection equipment, installed by B), B's PHS connection equipment, and B's broader telephone network. Critically, a single entrance line was sufficient to enable such two-way communication for the area covered by the base station it served.

The "entrance line usage right" was the right for a PHS operator like X, relying on B's network, to have a specific entrance line installed by B (with X bearing the cost) and to use that line to interconnect its specific base station with B's specific PHS connection equipment. This interconnection, in turn, enabled B to provide telecommunication services via its network to X's PHS customers within that base station's coverage area.

As part of the PHS business acquisition from Company A, X acquired 153,178 existing entrance line usage rights, each at a price of ¥72,800 (totaling approximately ¥11.15 billion). Subsequently, X also acquired new entrance line usage rights as needed by applying to B for the installation of new lines, paying ¥72,800 per line to cover installation and procedural costs. X then put all these acquired rights to use in its PHS business.

For corporate income tax purposes, X treated each individual entrance line usage right as a separate "minor depreciable asset". This was because the acquisition cost per right (¥72,800) was below the ¥100,000 threshold stipulated in Article 133 of the Corporate Tax Act Enforcement Order (the version before a 2004 amendment). This classification allowed X to deduct the full acquisition cost of these rights as an expense in the business year they were acquired and put into service.

The head of the competent tax office, Y (the appellant), disagreed with this treatment. Y contended that the entrance line usage rights did not qualify as minor depreciable assets, presumably arguing that the numerous rights should be aggregated or otherwise treated as a single, larger asset exceeding the ¥100,000 threshold. Consequently, Y issued a corrective corporate tax assessment against X. X challenged this assessment in court.

The Legal Framework: Minor Depreciable Assets and the "Unit" Question

Generally, when a company acquires fixed assets (other than land) that are used in its business and diminish in value over time or through use, these are classified as "depreciable assets". The cost of acquiring such assets is not expensed entirely in the year of acquisition but is instead allocated (depreciated) over the asset's useful life. This aligns with the accounting principle of matching expenses with the revenues they help generate over several periods.

However, Japanese corporate tax law provides an exception for certain low-value assets. Article 133 of the Corporate Tax Act Enforcement Order allows for "minor depreciable assets"—those with an acquisition cost of less than ¥100,000 (or for assets with a useful life of less than one year)—to be fully expensed in the business year they are put into service, provided the company accounts for them as an expense. This special treatment is generally understood to be because such assets are considered to lack sufficient materiality to warrant the complexities of formal depreciation procedures.

The dispute in this case centered on how to determine the "acquisition cost" for the purpose of this ¥100,000 threshold when multiple similar items are acquired. Specifically, what constitutes a single "unit" of a depreciable asset? The law itself did not explicitly define this "unit of determination". A relevant administrative guideline, Corporate Tax Basic Circular 7-1-11, stated that the determination should be made "for each unit that is normally traded as such". Prior to this case, there were no Supreme Court precedents directly addressing this issue of the unit of determination for minor depreciable assets.

The lower courts (Tokyo District Court and Tokyo High Court) had sided with X. The first instance court, for example, held that the determination should be based on "the unit capable of performing its function as an asset in the company's business activities, viewed generally and objectively". It found that a single entrance line usage right could indeed perform its function of interconnection and thus qualified as the unit. The tax office (Y) appealed these decisions to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Two-Pronged Analysis: Trading Unit and Functional Capability

The Supreme Court dismissed the tax office's appeal, thereby affirming that each entrance line usage right should be treated as an individual asset unit for the purpose of the minor depreciable asset rule.

The Court's reasoning can be seen as having two main components:

- The Trading Unit: The Court first observed that, based on the facts, "entrance line usage rights are transacted as a unit of one right per entrance line". X acquired these rights from Company A at a price of ¥72,800 per single line right, and also acquired new rights from B on a similar per-line basis and cost. This established the customary way these specific rights were bought and sold.

- The Functional Capability of a Single Unit: The tax office (Y) argued that a single entrance line usage right, by itself, could not function as a source of revenue in X's PHS business, implying it needed to be part of a larger system to be functional. The Supreme Court explicitly rejected this argument.

- It stated that depreciable assets contribute to revenue generation by performing their inherent function according to their intended use within the business.

- The inherent function of an entrance line usage right in X's type of PHS business was to use a specific entrance line to interconnect one of X's specific base stations with one of B Company's specific PHS connection devices. This, in turn, enabled B Company to provide its network's telecommunication services to X's PHS customers within that base station's coverage area.

- Crucially, the Court noted that the factual record showed that "if there is one entrance line, two-way communication, such as calls from a PHS terminal within the area of the base station connected by that line to B Company's fixed-line or mobile phones, or calls from fixed-line or mobile phones to a PHS terminal in that area, becomes possible".

- Therefore, the Court concluded, "even a single right pertaining to one entrance line can perform the above-mentioned function in X's PHS business and contribute to revenue generation".

Based on these findings, the Supreme Court held that "it is appropriate to consider one right pertaining to one entrance line as a single depreciable asset". (The Court also cited the relevant provisions of the Corporate Tax Act and its Enforcement Order that classify telecommunication facility usage rights as depreciable assets ). Consequently, for applying the ¥100,000 threshold of Article 133 of the Enforcement Order, "the determination of whether the acquisition cost is less than ¥100,000 should be made for each such single right". Since X acquired each right for ¥72,800, "each one of these rights should be considered a minor depreciable asset as stipulated in the said article".

Distinguishing from Lower Court Reasoning (Slight Nuance)

While the Supreme Court reached the same ultimate conclusion as the lower courts, legal commentators have noted a slight difference in emphasis in their reasoning. The lower courts primarily focused on the "asset's functional capability" as the standard for determining the unit. The Supreme Court, however, first explicitly noted that the entrance line usage rights were "transacted as a unit of one right per entrance line" before addressing and affirming the functional capability of a single unit. This suggests the Supreme Court may have considered both the "trading unit" and the "functional unit" as relevant criteria, or perhaps used the functional analysis to confirm the appropriateness of the trading unit. Some academic views suggest that these two concepts—the unit in which an asset is normally traded and the unit in which it can perform its function—will often coincide in practice.

Implications and Broader Significance

The Supreme Court's decision in the NTT Docomo case has several important implications:

- Precedent for Unit Determination: It provides authoritative guidance from Japan's highest court on the previously unsettled issue of how to determine the "unit" of a depreciable asset for the purpose of the minor depreciable asset rule.

- Emphasis on Individual Functionality and Trading Norms: The ruling underscores that if an individual component of a larger system is customarily traded as a distinct unit and can independently perform its core intended function within the business, contributing to revenue, it can be treated as a separate asset for depreciation purposes.

- Potential for Structuring Acquisitions?: A significant point of discussion among commentators is the potential policy implication of this ruling. The concern is that by allowing assets to be judged on such an individual basis, companies might be incentivized to disaggregate what are effectively large, integrated investments into numerous sub-¥100,000 units simply to qualify for immediate expensing. In X's case, while each line right was individually inexpensive, the total initial acquisition involved over 150,000 rights at a cost exceeding ¥11 billion. Allowing such a substantial investment to be expensed immediately based on the low cost of its individual components has raised eyebrows.

- Possible Legislative Responses: In light of such concerns, some commentators have pointed to potential legislative or administrative responses, such as establishing an aggregate annual cap on the total amount that can be expensed under the minor depreciable asset rule, similar to provisions like Section 179 of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment in the NTT Docomo case adopted a practical approach to defining the unit of a depreciable asset, giving weight to both how the asset components are commonly transacted and their individual capacity to perform their intended function within the business. By affirming that each ¥72,800 entrance line usage right was a distinct minor depreciable asset, the Court allowed for their immediate expensing. While providing clarity on the "unit of determination," the decision also spurred discussion on the broader policy objectives and potential vulnerabilities of the minor depreciable asset rule when applied to large-scale acquisitions of individually low-cost, but collectively significant, assets.