Deportation Stays and the Right to Appeal: A 1977 Japanese Supreme Court Decision

Decision Date: March 10, 1977

Case Number: Showa 51 (Gyo-Fu) No. 5 – Appeal Against Dismissal of Appeal Concerning Decision on Motion for Stay of Execution of Administrative Disposition

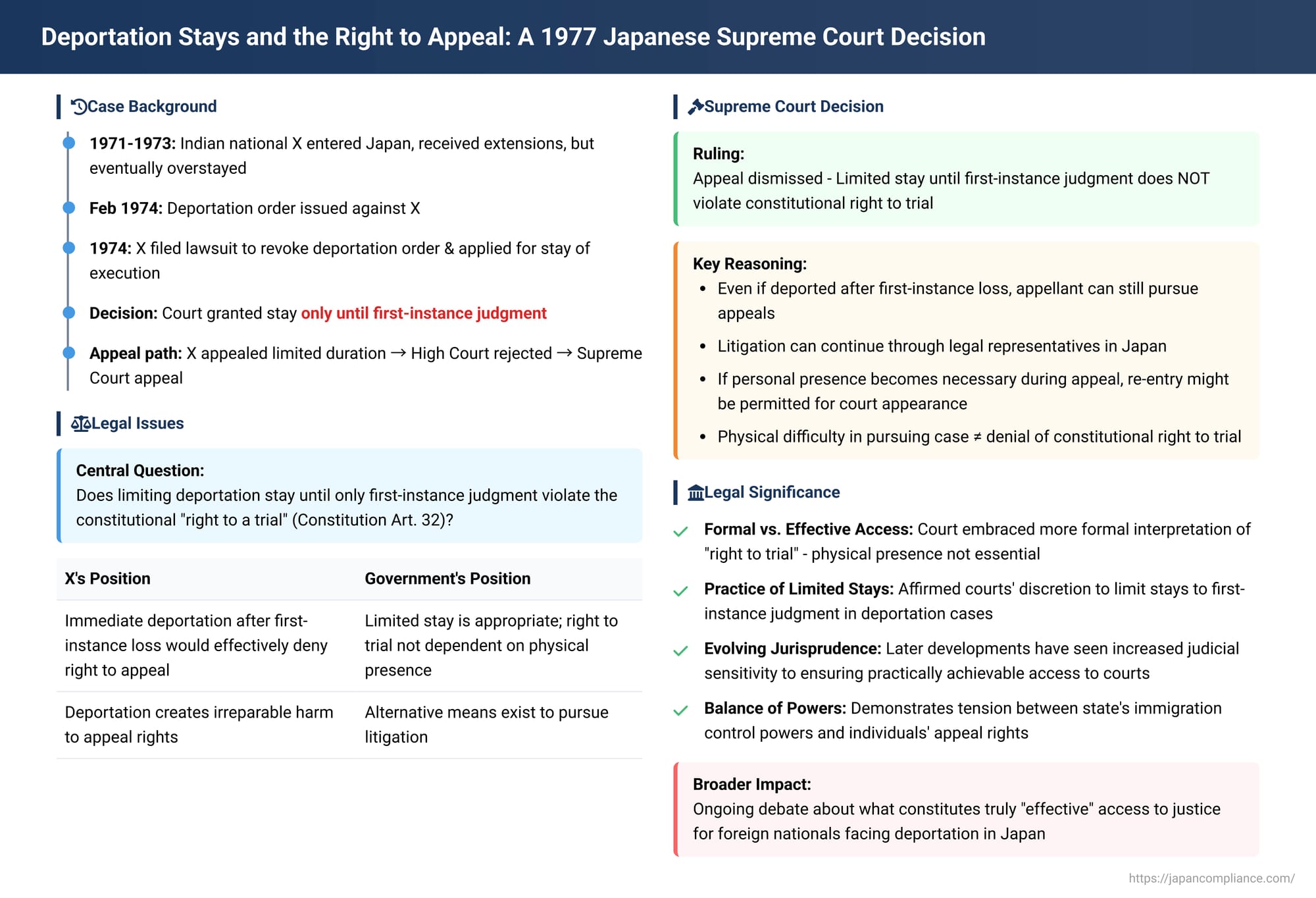

When a foreign national faces a deportation order from Japan, they can challenge that order in court. To prevent being removed from the country while the case is ongoing, they can also apply for a "stay of execution" – a court order temporarily halting the deportation. A critical question arises if this stay is granted only for a limited time, for example, until the first court delivers its judgment. If the individual loses at this first stage, and the stay expires, they could be deported immediately. Does this situation effectively deny their constitutional "right to a trial," particularly their right to appeal to higher courts? A 1977 Japanese Supreme Court decision addressed this precise concern.

The Case of the Contested Deportation

The appellant, X (A.S.J., an Indian national), had entered Japan on February 7, 1971, with a 180-day landing permit specifically for the purpose of pursuing unrelated litigation in Japanese courts. He subsequently received three extensions of his period of stay. However, his fourth application for an extension was denied, and his authorized period of stay officially expired on January 26, 1973.

As a result, on February 28, 1974, the Chief Examiner of the Kobe Immigration Office issued a deportation order (退去強制令書 - taikyo kyōsei reisho) against X, based on him overstaying his visa. X responded by filing a lawsuit in the Kobe District Court to revoke the deportation order. Simultaneously, he applied for a stay of execution of the deportation order, requesting that it be halted until a final judgment was reached in his main revocation lawsuit.

The Kobe District Court granted a partial stay. It ordered that the repatriation (送還 - sōkan) part of the deportation order (i.e., the physical act of sending X out of Japan) be stayed, but significantly, this stay was limited in duration: only "until the pronouncement of the judgment in the main case at the first instance." The detention (収容 - shūyō) part of the deportation order, which can occur pending repatriation, was not explicitly stayed by this particular phrasing, though the primary concern was the act of removal.

X filed an immediate appeal against the limited duration of this stay, but the Osaka High Court upheld the District Court's decision, deeming the limited stay appropriate. X then lodged a special appeal with the Supreme Court. His core argument was that limiting the stay of deportation until only the first-instance judgment was unconstitutional. If he were to lose his case at the first instance, the deportation order would be immediately executed, and he would be forcibly repatriated. This, X contended, would effectively deny him his right to appeal the main case to higher courts, thereby violating his fundamental "right to a trial" guaranteed by Article 32 of the Constitution of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision (March 10, 1977)

The Supreme Court dismissed X's special appeal. While the dismissal was formally on procedural grounds (finding that the constitutional argument, as presented, did not meet the stringent requirements for a special appeal under the Code of Civil Procedure), the Court nevertheless addressed the substantive constitutional claim raised by X.

Why a Limited Stay Doesn't (Necessarily) Deny the Right to Appeal or a Trial

The Court reasoned that, even if X were to lose his case at the first instance and the deportation order were executed, this would not automatically deprive him of his right to appeal that decision and receive a trial in the higher courts.

The Court acknowledged certain practicalities:

- Difficulty in Personal Pursuit: If X were deported to his home country, it would undeniably become difficult for him to personally continue pursuing the lawsuit in Japan.

- Litigation via Legal Representative: However, it would still be possible for X to continue the lawsuit through a legal representative (i.e., his attorney) in Japan.

- Possibility of Re-entry for Court Appearance: Furthermore, the Court noted that if X's direct physical presence in court became necessary during the appeal process (for example, for questioning as a party in the case), it was not out of the question that he could be permitted to re-enter Japan for that specific purpose through prescribed immigration procedures at that time.

Based on these considerations, the Supreme Court concluded that even if the deportation order were executed and X were repatriated after a first-instance loss, his constitutional right to a trial under Article 32 would not be denied. Since X's constitutional argument was predicated on the assumption that this right would be denied by the limited stay, and the Court found this premise incorrect, his claim of unconstitutionality failed.

The "Right to a Trial" and Practical Realities of Deportation Stays

This decision touches on important aspects of the constitutional right to a trial and the practicalities of seeking stays of execution in deportation cases:

- Common Practice for Stays: Legal commentary notes that while stays of the repatriation part of deportation orders are often granted by courts due to the "irreparable harm" involved, the duration of such stays can vary. While many extend until the final judgment in the main case, some, as in X's situation, are limited to the pronouncement of the first-instance judgment or a short period thereafter.

- Rationale for Limited Stays: This practice of limiting the stay's duration is sometimes viewed as a "practical expediency" or "know-how" by the courts. Given that a high percentage of lawsuits challenging deportation orders are ultimately unsuccessful, limiting the initial stay allows the court to reassess the necessity of a continued stay after the merits of the case have been fully examined at the first instance. If the first court, after a thorough hearing, rules against the deportee, it might strengthen the argument that the conditions for a stay (particularly the negative requirement in ACLA Art. 25(4) that the main suit does not appear to have "no prospect of winning") are no longer met.

- Risk of a "Gap in Protection": A significant concern with stays limited to the first-instance judgment is the potential for a "gap in protection." If an individual loses at the first instance and is immediately deported, they must then apply for a new stay pending their appeal, and there's a period during which they are outside Japan and potentially unable to effectively manage this process before the appeal itself can be properly heard.

Evolving Understanding of "Effective Access to Justice"

The interpretation of Article 32 of the Constitution (the right to a trial) has evolved over time.

- Initially, it was often seen primarily as a formal guarantee of access to the courts—a right not to be refused a hearing if one meets the procedural requirements.

- However, contemporary constitutional scholarship increasingly views Article 32 as encompassing a more substantive right to "effective access to justice." This includes ensuring that judicial remedies are meaningful and that individuals have a practical opportunity to have their rights protected. This can extend to requiring adequate provisional relief (like a stay of execution) when necessary to prevent a subsequent judgment from becoming moot or a right from being irreparably harmed before it can be adjudicated.

- Some scholars criticized earlier court decisions that took a very formal view, for instance, by denying damages in a case where a person was deported so swiftly that they were prevented from even applying for a stay, arguing that this rendered the right to sue practically meaningless.

This 1977 Supreme Court decision, by emphasizing the continued possibility of litigation through a legal representative and the potential (though not guaranteed) for re-entry if X's presence were essential, appears to lean towards a more formal interpretation of the "right to a trial" in the specific context of deportation after a first-instance loss. It did not find that the appellant's continued physical presence in Japan throughout all appeal stages was an indispensable component of this right.

Legislative and Judicial Developments Since 1977

It is worth noting that the legal landscape concerning the rights of foreign nationals and provisional remedies has seen some development since this decision:

- For example, amendments to the Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Act have introduced a system for granting "permission for provisional stay" to asylum seekers during their refugee status determination process (Article 61-2-4), offering a form of protection.

- There has also been at least one notable Tokyo High Court decision (September 22, 2021) which found a constitutional violation where immigration authorities deliberately delayed notifying an individual of their appeal rejection until just moments before their scheduled deportation, an act the High Court deemed to have effectively robbed the individual of the opportunity for judicial review. This suggests an increasing judicial sensitivity to ensuring that access to the courts is not just formally available but practically achievable.

Despite these developments, some commentators argue that for deportation orders, which have such severe and often irreversible consequences, a more robust legislative solution—such as making such orders not immediately executable upon issuance or after a first-instance adverse judgment—might be necessary to fully protect an individual's right to exhaust their appellate remedies effectively.

Concluding Thoughts

The 1977 Supreme Court decision in A.S.J.'s case illustrates the complex interplay between the state's sovereign power to control immigration and enforce deportation orders, and an individual's fundamental constitutional right to access the courts and pursue appeals. While acknowledging the practical difficulties that deportation would impose on an appellant, the Court found that the availability of legal representation and the theoretical possibility of re-entry for essential court appearances meant that a stay of deportation limited to the first-instance judgment did not, in itself, constitute a denial of the right to a trial. The case continues to be a reference point in ongoing discussions about what constitutes truly "effective" access to justice for foreign nationals facing deportation in Japan, and the appropriate scope and duration of provisional remedies like stays of execution.