Dependent Status Disputes in Japan's Health Insurance: Supreme Court Clarifies Appeal Routes (2022)

TL;DR

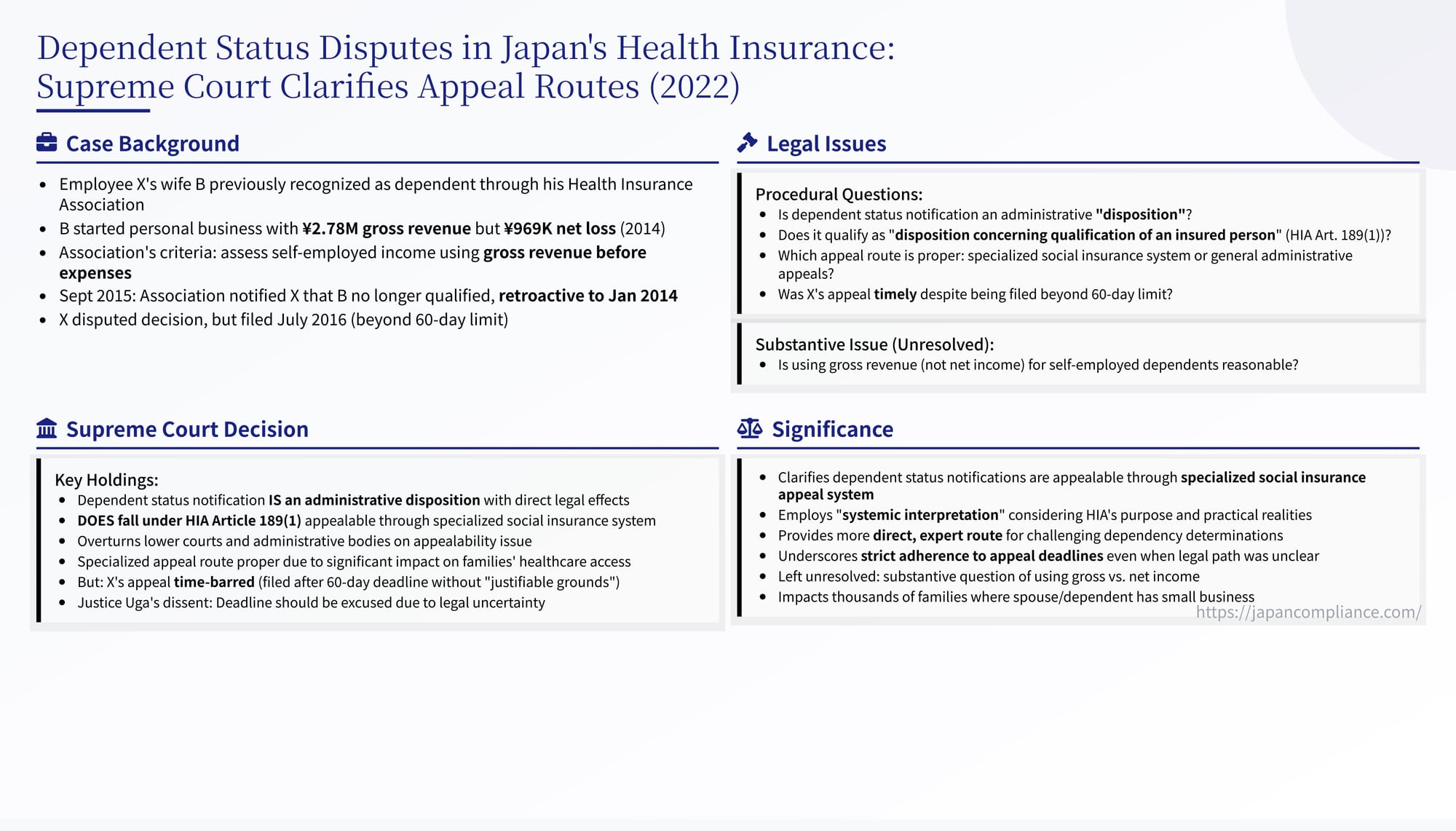

Japan’s Supreme Court (Dec 13 2022) held that a notice revoking a spouse’s dependent status under the Health Insurance Act is an appealable administrative disposition. Such disputes must first go through the special two‑tier social‑insurance appeal system, but strict 60‑day filing limits apply—here, the claimant lost on timeliness.

Table of Contents

- Background: Dependent Status, Income Thresholds, and a Health Insurance Association's Decision

- The Appeals Process: Navigating Social Insurance Review

- The Lawsuit: Challenging Both the Notice and the Appeal Dismissals

- The Supreme Court's Decision: A Pivotal Interpretation but a Procedural Defeat

- Significance and Analysis

- Conclusion

Social insurance systems often involve complex eligibility determinations, not just for the primary insured individual but also for their dependents. When an insurer decides that a family member no longer qualifies as a dependent – a decision that can significantly impact healthcare access and financial obligations – what recourse does the insured person have? Specifically, what administrative and judicial appeal routes are available? A 2022 decision by Japan's Supreme Court addressed a critical procedural question within the context of the Health Insurance Act (HIA): Is a health insurance association's notification that a spouse is no longer considered a dependent an administrative "disposition" subject to the specialized social insurance appeal process? This case, formally the Case Concerning Request for Revocation of Disposition, etc. (Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, Reiwa 3 (Gyo-Hi) No. 120, Dec. 13, 2022), provides important clarification on the legal nature of such determinations and the proper channels for challenging them, even as the appellant's specific claims ultimately failed on timeliness grounds.

Background: Dependent Status, Income Thresholds, and a Health Insurance Association's Decision

The appellant, X, was an employee insured under Japan's Health Insurance system through his employer's designated Health Insurance Association (健康保険組合, kenkō hoken kumiai – referred to here as Association A, later succeeded by appellee Y1). Health Insurance Associations are public corporations established primarily by large employers or groups of employers to administer health insurance for their employees and dependents.

X's wife, B, had previously been recognized by Association A as his dependent (被扶養者, hifuyōsha) under the Health Insurance Act (HIA Art. 3(7)). Dependent status is crucial because it typically grants the dependent coverage under the employee's health insurance plan without requiring separate premium payments. To qualify as a dependent, an individual must meet specific relationship criteria (e.g., spouse, child) and primarily rely on the insured employee for financial support, generally falling below certain income thresholds.

B worked part-time but also started a personal business in January 2014. For the calendar year 2014, B's gross revenue (uriage kingaku) from her business was approximately ¥2.78 million. However, after deducting business costs and expenses (uriage genka to keihi), her net business income (shotoku kingaku) was negative (a loss of approximately ¥969,000).

Association A had established its own internal handling criteria (toriatsukai kijun) for determining dependent status, including income thresholds. Critically, for dependents engaged in self-employment, the Association's criteria stipulated that annual income would be assessed based on gross revenue before deducting necessary expenses. Based on this criterion, B's gross revenue of ~¥2.78 million exceeded the Association's income threshold for dependents (typically ¥1.3 million per year).

Consequently, on September 10, 2015, Association A issued a notice (本件通知, honken tsūchi) to X. This notice informed X that, based on her income exceeding the standard, his wife B was deemed to no longer qualify as a dependent, effective retroactively from January 1, 2014.

The immediate consequence for B was the loss of coverage under X's health insurance. Unless she enrolled in another system (like National Health Insurance, requiring separate premiums), she would lack public health insurance coverage.

The Appeals Process: Navigating Social Insurance Review

X disputed the Association's decision, likely disagreeing with the use of gross revenue instead of net income for assessing his wife's financial dependency. He attempted to challenge the notice through the specialized administrative appeal system set up for social insurance matters.

- Health Insurance Act Article 189(1): This provision establishes a two-tiered appeal process for specific administrative actions under the HIA. It states that a person dissatisfied with a "disposition concerning the qualification of an insured person, standard remuneration, or insurance benefits" (hoken-sha no shikaku, hyōjun hōshū mata wa hoken kyūfu ni kansuru shobun) must first file a request for examination (shinsa seikyū) with a regional Social Insurance Examiner (shakai hoken shinsakan). If dissatisfied with the Examiner's decision, they can then file a request for re-examination (sai-shinsa seikyū) with the national Social Insurance Appeals Committee (shakai hoken shinsakai). Decisions of the Appeals Committee can then typically be challenged in court via administrative litigation.

- X's Appeals: In July 2016 (significantly later than the September 2015 notice), X filed a request for examination with the Kinki Regional Social Insurance Examiner, asserting that the Association's notice regarding B's dependent status fell under Article 189(1).

- Examiner's Decision (August 2016): The Examiner dismissed (kyakka) the appeal, ruling that the Association's notice was not a "disposition" covered by Article 189(1). The reasoning was that Article 189(1)'s reference to "disposition concerning the qualification of an insured person" corresponded only to the formal confirmation of the insured person's own eligibility under HIA Article 39(1), and did not encompass determinations about dependent status.

- Appeals Committee's Decision (March 2017): X requested re-examination. The Social Insurance Appeals Committee also dismissed the appeal (saiketsu), upholding the Examiner's reasoning that a notice regarding dependent status was not an appealable disposition under Article 189(1).

The Lawsuit: Challenging Both the Notice and the Appeal Dismissals

Having exhausted the administrative appeal route (which had refused to consider the merits), X filed suit in court. The lawsuit had two main components:

- Against the Association (Y1): Seeking the revocation (torikeshi) of the original September 2015 notice, arguing that B did meet the criteria for dependent status (implicitly challenging the Association's use of gross revenue).

- Against the State (Y2): Seeking the revocation of the Appeals Committee's final decision dismissing his appeal, and also seeking damages under the State Compensation Act, arguing that the decisions by both the Examiner and the Committee (dismissing his appeals on procedural grounds) were illegal.

The lower courts (Hiroshima District and High Courts) agreed with X that the Association's original notice was an administrative disposition subject to judicial review. However, they upheld the Association's substantive decision (finding B non-dependent based on the gross revenue criterion, deeming the criterion within the Association's discretion). Crucially, they also agreed with the Examiner and Committee that the notice regarding dependent status was not a "disposition concerning the insured person's qualification" under HIA Article 189(1), meaning X should have used the general administrative appeal process, not the specialized social insurance one. Therefore, they upheld the Committee's decision to dismiss the appeal and denied the related claims against the State.

X sought review by the Supreme Court, focusing on the interpretation of HIA Article 189(1).

The Supreme Court's Decision: A Pivotal Interpretation but a Procedural Defeat

The Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court issued a complex ruling that significantly clarified the law but ultimately resulted in the dismissal of X's claims.

1. Legal Nature of the Dependent Status Notice:

The Court first established, agreeing with the lower courts on this point, that the Health Insurance Association's notification to X stating his wife B was no longer a dependent does constitute an administrative disposition (shobun) subject to legal challenge. Its reasoning focused on the direct legal effects:

- Determines Applicable Insurance: The determination of dependent status directly dictates which public health insurance system applies to the individual (HIA as a dependent vs. NHI as an insured person).

- Impacts Rights and Obligations: This determination affects eligibility for specific insurance benefits (family benefits under HIA vs. individual benefits under NHI) and liability for premiums (no direct premium for HIA dependents vs. premium/tax liability under NHI).

- Affects Access to Care: Critically, under Japan's system where insurance cards are generally required for accessing insured medical treatment, the non-issuance of a dependent's card (following a non-dependency finding) can create significant practical barriers to receiving timely medical care unless the individual takes steps to enroll in NHI.

- Need for Legal Certainty: Given these substantial impacts on legal status and daily life, the Court found a high degree of necessity for ensuring legal certainty and providing effective remedies regarding these determinations, similar to the need for certainty regarding the insured person's own qualification status (which is explicitly subject to formal confirmation).

- Implied Legal Framework: The Court inferred that the HIA and its implementing regulations implicitly assume that insurance associations will make these determinations and notify the affected parties, making the notification a legally significant act regulating their status, not merely conveying information.

2. Appealability under HIA Article 189(1):

This was the core legal issue where the Supreme Court overturned the lower courts and the administrative appeal bodies. The Court held that a health insurance association's notification of non-dependency does fall under the category of a "disposition concerning the qualification of an insured person" (hoken-sha no shikaku ni kansuru shobun) as used in Article 189(1).

- Purpose of the Special Appeal System: The Court reasoned that the purpose of establishing the specialized two-tier appeal system (Examiner and Committee) under Article 189(1) was to provide simple, prompt relief through expert bodies for administrative decisions having a significant impact on the lives of numerous insured persons and their families.

- Dependent Status Fits the Purpose: Determinations about dependent status clearly fall within this rationale. They directly affect the scope of insurance coverage for the family unit, determine financial obligations (premiums), and impact access to essential healthcare. The need for expert, expedited review is just as strong, if not stronger, for dependent status issues as it is for the primary insured's status or benefit amount disputes.

- Conclusion: Therefore, the Court concluded, the purpose and structure of the law support interpreting Article 189(1) broadly enough to include notifications regarding dependent status. This means that the proper route for challenging such a notification is indeed the specialized appeal process starting with the Social Insurance Examiner.

3. Timeliness of the Appeal:

Having established that X should have used the Article 189(1) appeal process, the Court then examined whether he had done so correctly.

- Statutory Time Limit: The relevant law governing these appeals (the Social Insurance Examiner and Appeals Committee Act, or Shashinhō, before its 2014 amendment) stipulated in Article 4(1) that a request for examination must be filed within 60 days from the day after learning of the disposition.

- X's Appeal was Late: X received the notice in September 2015 but did not file the request for examination until July 2016, well beyond the 60-day limit.

- "Justifiable Grounds" Exception: The law contained an exception (Art. 4(1) proviso) allowing late filing if the claimant could demonstrate "justifiable grounds" (seitō na jiyū) for the delay.

- Majority Finding: The majority opinion, without detailed reasoning on this point, simply stated that X's appeal was filed after the time limit had passed and was therefore unlawful (futekihō). This implies the Court found no "justifiable grounds" to excuse the delay.

- Justice Uga's Dissent on Timeliness: Justice Uga strongly dissented on this specific point. He argued that the term "justifiable grounds" (seitō na jiyū) in the Shashinhō should be interpreted more broadly than the stricter standard ("unavoidable reason," yamu o enai riyū) found in the old general administrative appeal law (the old ACRA). He contended it should align with the term "justifiable reason" (seitō na riyū) used in the revised ACRA and the Administrative Case Litigation Act, where failure by the agency to properly inform the claimant of their appeal rights (教示義務, kyōji gimu) is generally considered "justifiable reason" excusing delay. Given that such notification was likely inadequate or absent in this case (since the common understanding, even among administrators, was that this type of notice wasn't appealable under Art. 189), Justice Uga argued that "justifiable grounds" existed, the appeal should be deemed timely, and the case remanded for a decision on the merits of the dependent status determination.

4. Procedural Consequences:

- Claim Against the State (Y2): Since the majority found the initial appeal to the Examiner to be time-barred and thus unlawful, the subsequent re-examination request to the Appeals Committee was also necessarily invalid. Therefore, the Appeals Committee's final decision (本件裁決) dismissing the re-examination request reached the correct outcome (dismissal), even though its stated reason (that the original notice wasn't appealable) was wrong according to the Supreme Court's new interpretation. Because the Committee's dismissal was ultimately correct in outcome, the claim seeking its revocation failed. The related claim for state compensation also failed, as the administrative appeal bodies could not be deemed negligent for dismissing an appeal that was, in fact, time-barred.

- Claim Against the Association (Y1): Health Insurance Act Article 192 requires that administrative appeals under Article 189 must be pursued (and a final decision received) before filing a lawsuit in court challenging the underlying disposition (this is known as the exhaustion of administrative remedies requirement, or 不服申立前置主義, fufuku mōshitate zenchi shugi). Because X's administrative appeal was found to be time-barred and thus improperly pursued, he had failed to meet this mandatory prerequisite. Therefore, the Supreme Court ruled ex officio that the lawsuit against the Association (Y1) seeking revocation of the original notice was procedurally improper and must be dismissed (kyakka). The Court therefore vacated the parts of the lower court judgments that had ruled on the merits of this claim.

Significance and Analysis

The 2022 Supreme Court decision carries significant weight for understanding administrative procedure and judicial review within Japan's complex social insurance system.

- Dependent Status Notifications are Appealable "Dispositions": The primary significance is the Court's clear ruling that a health insurance association's determination of dependent status, communicated via notice, is indeed an administrative disposition with direct legal effects, and further, that it qualifies as a "disposition concerning the insured person's qualification" appealable under the specialized procedures of HIA Article 189(1). This overturns long-standing administrative practice and previous lower court interpretations, providing insured persons and their families with a more direct, expert, and potentially faster route for challenging dependency determinations compared to relying on the general administrative appeal system or direct court action (which is now barred unless the specialized appeal is exhausted).

- "Systemic Interpretation" Approach: The Court's method for reaching this conclusion is noteworthy. Faced with statutory silence on the specific nature of dependent status determinations, it employed a "systemic interpretation" (shikumi kaishaku), looking at the purpose of the relevant provisions within the broader context of the HIA, related regulations (like those concerning dependent notification forms and insurance cards), the practical realities of the universal healthcare system (importance of insurance cards for access), and the overall goal of providing effective remedies. This purposive and systemic approach allowed it to overcome a purely literal reading of "insured person's qualification."

- Strict Adherence to Time Limits: Despite establishing a clearer appeal path, the decision underscores the critical importance of adhering to statutory time limits for filing administrative appeals. The majority's refusal to excuse the delay, even where the appealability of the notice was previously unclear and likely not properly communicated, highlights the unforgiving nature of these deadlines under the existing interpretation of the Shashinhō (Social Insurance Examiner and Appeals Committee Act). Justice Uga's dissent points to a potential tension with broader principles of access to justice and the interpretation of "justifiable grounds" in other administrative law contexts, suggesting this area might see future debate or legislative clarification.

- Substantive Issue Left Unresolved: Because the case was ultimately decided on the procedural ground of timeliness, the Supreme Court did not rule on the underlying substantive issue: whether the health insurance association's internal rule using gross revenue, rather than net income after expenses, to assess the income of a self-employed dependent was reasonable or lawful. This issue, which has significant implications for dependents with small businesses or freelance work, remains largely within the discretion of individual insurance associations or potentially subject to future legislative clarification.

Conclusion

The 2022 Supreme Court judgment significantly clarified the procedural landscape for disputes over dependent status in Japan's employee health insurance system. It established that notifications denying dependent status are indeed administrative dispositions appealable through the specialized social insurance review process (Social Insurance Examiner and Appeals Committee). This potentially offers a more accessible and expert forum for resolving such disputes. However, the ruling also served as a stark reminder of the strictness of procedural time limits, as the appellant's claims ultimately failed for having missed the statutory deadline for the initial administrative appeal. While providing crucial procedural clarity, the decision left the substantive question regarding income calculation methods for self-employed dependents unanswered by the highest court.