Delegating Director Pay in Japan: Shareholder Oversight and Board Discretion in Severance Allowances

Case: Action for Confirmation of Nullity of a Shareholders' Meeting Resolution

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of December 11, 1964

Case Number: (O) No. 120 of 1963

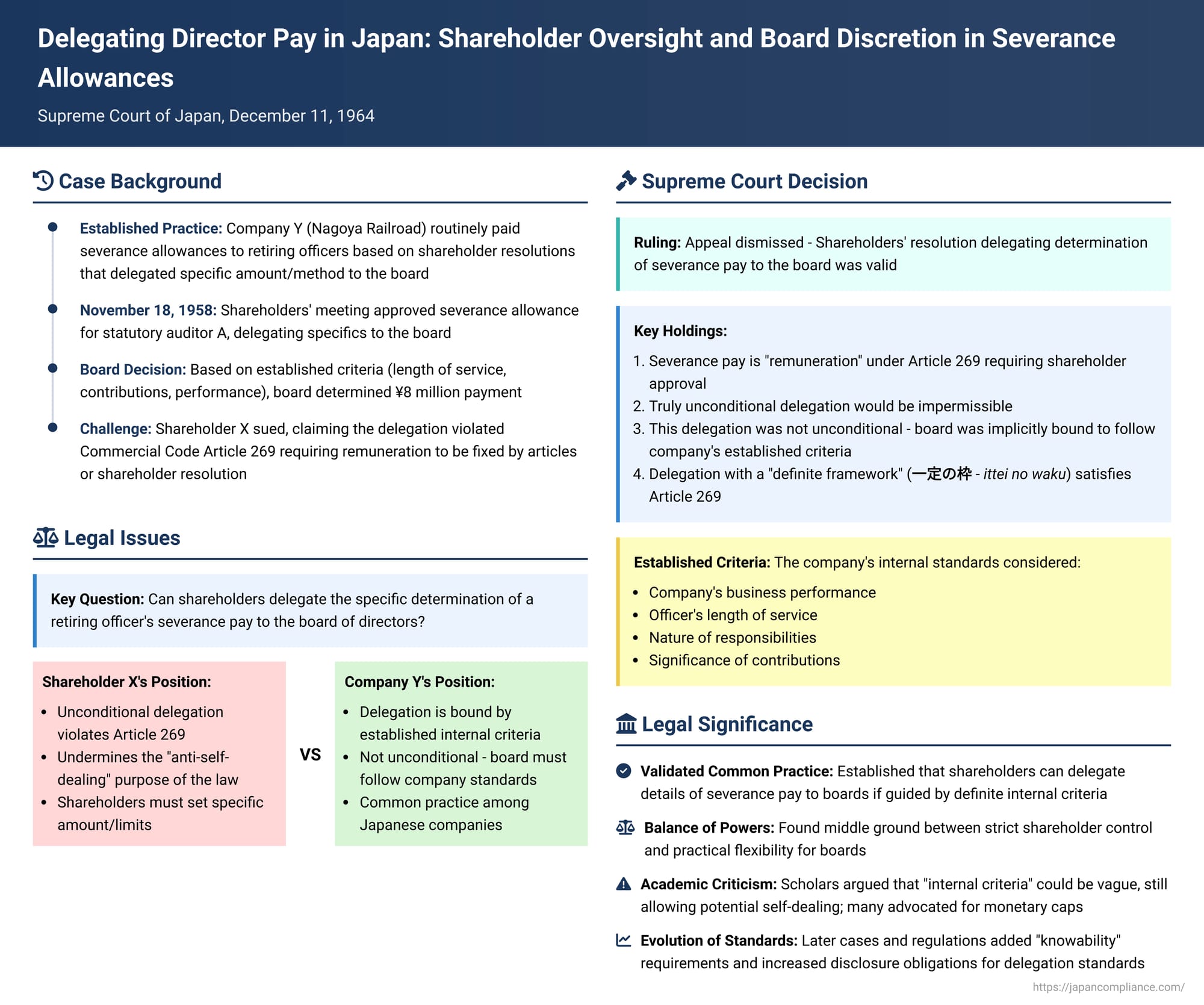

The remuneration of company directors and other officers is a matter of significant corporate governance concern. In Japan, a long-standing legal principle dictates that such compensation must be determined either by the company's articles of incorporation or by a resolution of its shareholders' meeting. This rule aims to prevent directors from unilaterally setting their own pay, a practice often referred to as "self-dealing" or "lining one's own pockets" (お手盛り - oteshimori). A key Supreme Court decision on December 11, 1964, addressed the nuances of this principle, particularly concerning retirement severance allowances (退職慰労金 - taishoku irōkin) and the extent to which shareholders can delegate the specifics of these payments to the board of directors.

A Severance Pay Dispute: Facts of the Case

The defendant, Company Y (Nagoya Railroad Co., Ltd.), had an established practice for granting severance allowances to its retiring officers. According to this practice, each time an officer retired, the shareholders' meeting would pass a resolution authorizing the payment of a severance allowance but would delegate the task of determining the specific amount, timing, and method of payment to the company's board of directors. The board, in turn, was expected to make this determination based on a set of established internal criteria. These criteria took into account various factors, including the company's overall business performance, the retiring officer's length of service, the nature of their responsibilities, and the significance of their contributions to the company.

This practice came under scrutiny following a shareholders' meeting of Company Y held on November 18, 1958. At this meeting, a resolution was passed concerning the granting of a retirement severance allowance to A, a retiring statutory auditor. Consistent with its past practice, the shareholders' meeting resolved to delegate the determination of the specifics of A's severance package to the board of directors. The board subsequently decided to pay A a severance allowance of 8 million yen.

X, a shareholder of Company Y, challenged this shareholders' meeting resolution by filing a lawsuit. X argued that the resolution was an illegal and unconditional delegation of authority to the board of directors. According to X, such an open-ended delegation violated the then-Commercial Code Article 269, which mandated that officer remuneration be fixed either by the articles of incorporation or by a resolution of the shareholders' meeting. X contended that if a company's established internal practices could legitimize such a broad delegation for severance pay, then Article 269 would effectively become a meaningless provision, easily circumvented.

Lower Courts' Rulings: Implied Standards Validate Delegation

The court of first instance (Nagoya District Court, judgment dated September 19, 1961) dismissed X's claim. The court found that the shareholders' resolution, when viewed in the context of Company Y's long-standing practice and internal standards, was not an unconditional delegation. It held that there was an implicit understanding and restriction that the board of directors must adhere to the company's established criteria when determining the severance amount.

The appellate court (Nagoya High Court, judgment dated October 31, 1962) upheld the first instance court's decision and dismissed X's appeal, reaffirming that the delegation was permissible because it was implicitly guided by these internal standards. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Affirmation: Delegation Within a Framework is Lawful

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding the validity of the shareholders' meeting resolution.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: The "Definite Framework" Test

The Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Severance Pay as "Remuneration": The Court first affirmed that a retirement severance allowance, to the extent that it is paid as consideration for the officer's services rendered during their tenure, falls within the definition of "remuneration" (hōshū) as used in Articles 280 and 269 of the then-Commercial Code. Therefore, if the amount of such severance pay is not already stipulated in the company's articles of incorporation, it must be determined by a resolution of the shareholders' meeting.

- Unconditional Delegation Impermissible: The Court agreed with the appellant X's general proposition that an unconditional delegation of the determination of officer remuneration (including severance pay) to the board of directors is not permitted under the law. This would indeed undermine the shareholder oversight intended by Article 269.

- This Specific Delegation Was Not Unconditional: However, the Supreme Court then diverged from X's application of this principle to the facts of the case. It upheld the factual findings of the lower courts, which established that Company Y's resolution to delegate the decision regarding auditor A's severance pay was not intended to be an unconditional delegation. Instead, based on the company's well-established practice, it was implicitly understood that the board of directors was to determine the amount, timing, and method of payment in accordance with the company's pre-existing, definite internal criteria. These criteria involved considering factors such as the company's performance, the officer's years of service, their specific duties and responsibilities, and the level of their contribution and achievements.

- "Definite Framework" Satisfied Legal Requirements: Because the delegation was implicitly bound by these established standards, the Supreme Court concluded that the shareholders' meeting resolution had, in effect, established a "definite framework" or "certain limits" (ittei no waku) within which the board was to operate. This, the Court found, was sufficient to satisfy the underlying purpose of Article 269, which is to ensure shareholder control over officer remuneration and prevent arbitrary or excessive payments decided solely by the directors themselves. Therefore, the resolution was not invalid.

Analysis and Implications: Balancing Shareholder Control and Board Practicality

This 1964 Supreme Court decision has been a significant reference point in Japanese corporate law regarding the determination of officer remuneration, particularly for retirement severance allowances.

- The Purpose of Regulating Officer Remuneration:

The requirement that officer remuneration be set by the articles of incorporation or a shareholders' resolution dates back to the earliest versions of the Japanese Commercial Code in the Meiji era (e.g., Article 196 of the 1890 Code). The primary policy objective behind this rule (now found in Article 361 of the Companies Act for directors, and Article 387 for auditors in certain companies) is to prevent "self-dealing" (oteshimori) by directors. If directors could determine their own compensation without any external oversight, there would be a clear risk of them awarding themselves excessive amounts, to the detriment of the company and its shareholders. While some legal scholars have argued that this rule is merely a natural consequence of the principle that the body responsible for appointing an officer (the shareholders' meeting for directors) should also determine their pay (a "non-policy theory"), the anti-self-dealing rationale is widely accepted as the dominant policy consideration. - What Constitutes "Remuneration"?

The term "remuneration" is broadly construed to include any form of compensation provided by the company to its officers in exchange for their services, regardless of its specific name. This includes salaries, bonuses, and, as affirmed in this case and others, retirement severance allowances. The current Companies Act (Article 361, Paragraph 1) explicitly includes bonuses within the scope of remuneration that requires such approval. (It also effectively prohibits the payment of bonuses to directors through a distribution of profits, as per Article 452).

The inclusion of retirement severance allowances (taishoku irōkin) within this regulatory framework has been consistently upheld by Japanese case law and supported by most legal scholars, primarily on the grounds that such allowances represent a form of deferred compensation for services rendered during the officer's tenure. Arguments that severance pay falls outside this regulation because the recipient is already retired (and thus the payment isn't strictly for ongoing service under a current employment/mandate contract) have generally been rejected, especially in light of the strong anti-self-dealing policy. The regulation aims to cover any significant financial benefits flowing from the company to its officers that could be subject to abuse if left solely to the discretion of those officers. - Methods of Shareholder Determination of Remuneration:

- Ongoing Remuneration (Salaries, Regular Bonuses): For serving directors, a long-standing and court-approved practice in many Japanese companies has been for the shareholders' meeting to approve a total maximum aggregate amount of remuneration for all directors combined. The board of directors is then delegated the authority to decide the specific allocation of this total sum among the individual directors. This approach is generally considered to satisfy the anti-self-dealing objective, as the shareholders retain control over the overall financial commitment. Such a cap, once set, does not necessarily need to be re-approved at every annual meeting if it remains unchanged.

The 2019 revision to the Companies Act introduced further requirements for certain types of listed companies (e.g., those with an audit and supervisory committee or a U.S.-style three-committee structure). If these companies do not set individual directors' remuneration in the articles or by shareholder resolution, their boards must establish a policy for determining individual remuneration, and an outline of this policy must be disclosed in the annual business report. - Retirement Severance Allowances – The Impact of the 1964 Ruling:

The determination of severance pay presented a slightly different challenge, as it often involves a payment to a single retiring individual, making the "total aggregate cap for all directors" approach less directly applicable if the aim is to delegate the determination of that individual's specific amount. Before this 1964 Supreme Court decision, while case law recognized severance pay as remuneration needing shareholder or articles-based approval, there was uncertainty about how specific this approval needed to be.

This Supreme Court judgment effectively "rescued" or validated the common corporate practice of shareholders' meetings delegating the specific determination of severance pay to the board, provided that such delegation was understood to be governed by established, definite internal company criteria. By finding that these criteria constituted a "definite framework" set by the shareholders, the Court allowed for a degree of flexibility for the board while notionally preserving shareholder oversight.

However, this aspect of the ruling drew criticism from many legal scholars. They argued that merely relying on internal "criteria" – which could be vaguely defined or still allow considerable discretion to the board in assessing an individual's "merit" or "contribution" – was insufficient to effectively prevent self-dealing. Many maintained that even for individual severance payments, the shareholders' meeting should approve a specific monetary amount or at least a clear upper limit for the payment.

- Ongoing Remuneration (Salaries, Regular Bonuses): For serving directors, a long-standing and court-approved practice in many Japanese companies has been for the shareholders' meeting to approve a total maximum aggregate amount of remuneration for all directors combined. The board of directors is then delegated the authority to decide the specific allocation of this total sum among the individual directors. This approach is generally considered to satisfy the anti-self-dealing objective, as the shareholders retain control over the overall financial commitment. Such a cap, once set, does not necessarily need to be re-approved at every annual meeting if it remains unchanged.

- The Evolution of "Established Criteria" and Disclosure Requirements:

Following this 1964 Supreme Court precedent, a notable lower court decision (the Kansai Electric Power case, Osaka District Court, 1969) adopted the Supreme Court's line that a specific monetary cap decided by shareholders was not strictly necessary if there was an established internal standard for calculating severance pay. However, this lower court added an important condition: the existence and general nature of these internal standards must be such that shareholders can easily become aware of them. If this "knowability" was lacking, the shareholders' resolution delegating the decision could still be deemed invalid.

Subsequent case law, including appellate decisions in the Kansai Electric Power case and another significant case involving Ajinomoto Co., further refined this "knowability" standard. These later rulings often held that if the existence of internal severance pay standards was documented (e.g., in board of directors' meeting minutes) and if shareholders had the opportunity to ask questions about these standards (for example, during the shareholders' meeting itself), then the "knowability" requirement was met, even if the detailed content of the standards was not proactively published to all shareholders. This interpretation also faced criticism from some academics as being too lenient and not sufficiently ensuring shareholder awareness.

The legal landscape has continued to evolve. Current regulations under the Companies Act (e.g., Article 82, Paragraph 2 of the Ordinance for Enforcement of the Companies Act) now explicitly require that if the determination of items like retirement severance pay is delegated to the board, the method of calculating such payments must be disclosed in the reference documents sent to shareholders in advance of a shareholders' meeting, especially when written or electronic voting is permitted. This represents a significant step towards greater transparency. - The Need for Clarity ("One-Meaningfulness") in Calculation Criteria:

Even if delegation based on established criteria is permissible, a further issue is the clarity and objectivity of those criteria. If the criteria are so vague or subjective that they do not lead to a reasonably ascertainable and non-arbitrary calculation of the severance amount (i.e., if they are not sufficiently "one-meaningful" - 一義的 - ichigiteki, such that applying the facts to the criteria yields a clear or narrowly defined amount), then the delegation might still be challenged as failing to meet the underlying purpose of the remuneration rules. Some later lower court decisions (e.g., a Tokyo District Court judgment in 1988) have emphasized that for a delegation based on criteria to be valid in preventing self-dealing, those criteria should be specific enough to lead to a largely non-discretionary, predictable calculation. - Broader Trends in Remuneration Disclosure:

The spirit of Japanese company law has increasingly moved towards greater transparency in officer remuneration. Following a 1962 Commercial Code revision that required details of director and auditor remuneration to be included in supplementary schedules to financial statements, it was generally understood that individual remuneration amounts should ideally be ascertainable. More recently, since 2010, listed Japanese companies have been required to disclose, in their annual securities reports, the individual remuneration details for any director or officer whose total annual compensation from the company and its subsidiaries is 100 million yen or more. There is also a trend among some companies to move away from opaque or highly discretionary retirement severance systems towards more transparent and predictable arrangements.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision of December 11, 1964, provided important, albeit controversial, guidance on a common corporate practice in Japan: the delegation of determining officer retirement severance allowances to the board of directors by a shareholders' meeting. The Court held that such delegation is permissible and does not violate the statutory requirement for shareholder or articles-based determination of remuneration, provided it is not unconditional but is instead implicitly or explicitly guided by established, definite internal company criteria for calculating such payments. This, in the Court's view, means the shareholders have effectively set a "definite framework."

While this ruling "rescued" a prevalent practice and allowed for some operational flexibility, it also sparked considerable debate among legal scholars about whether it sufficiently upheld the core anti-self-dealing purpose of the remuneration rules, particularly in the absence of a shareholder-approved specific monetary cap. Subsequent case law and, more significantly, regulatory reforms under the Companies Act have since pushed towards greater transparency and clarity regarding the standards and methods used when such delegations are made, ensuring that shareholders are better informed about how officer remuneration, including severance pay, is determined.