Delegated Decisions, Divided Liability: Supreme Court Clarifies Responsibility for "Senketsu" Expenditures

Judgment Dates: December 20, 1991

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Case Citations:

- Supreme Court Heisei 2 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 137 (Manager's Appeal)

- Supreme Court Heisei 2 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 138 (Residents' Appeal)

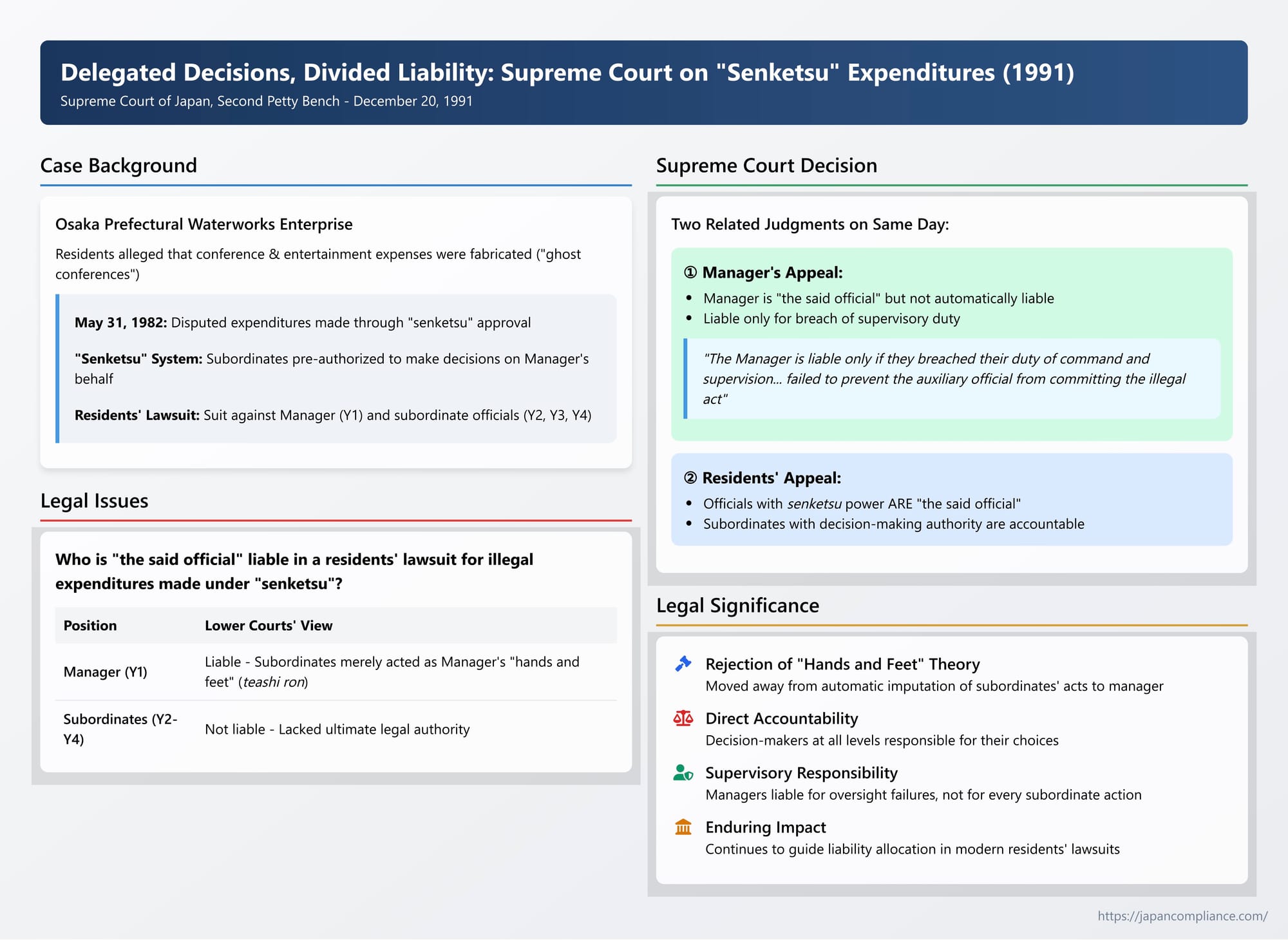

In the complex hierarchy of public administration, decisions are often made at various levels. A system known in Japan as "senketsu" (専決) allows higher-ranking officials to pre-authorize specific subordinate officials to make certain routine decisions on their behalf. But what happens when expenditures made under this senketsu system are alleged to be illegal? Who bears the financial responsibility in a residents' lawsuit – the top manager, the subordinate who made the decision, or both? A pair of landmark Supreme Court decisions issued on the same day in 1991 provided crucial clarification on this issue, particularly concerning the liability of officials in local public enterprises.

The Alleged "Ghost Conferences": Expenditures at the Osaka Waterworks

The cases originated from the Osaka Prefectural Waterworks Enterprise, a local public enterprise responsible for water services. Like other such enterprises, it was headed by a Manager (Y1 in this case) who had overall authority. The Osaka Prefectural Waterworks Department was the administrative body handling the Manager's duties.

Internal regulations of the Waterworks Department defined "kessai" (決裁) as the final decision-making authority resting with the Manager, and "senketsu" (専決) as the authority for designated subordinate officials to routinely make decisions on the Manager's behalf for specific matters. For budget execution, these rules stipulated that expenditures below certain amounts could be approved via senketsu by the Waterworks Department Director (Y2), Deputy Director (Y3), or the General Affairs Section Chief (Y4, specifically Mr. Okazaki in the relevant period).

A group of Osaka Prefecture residents (X et al., the plaintiffs) brought a residents' lawsuit under the Local Autonomy Act (specifically, Article 242-2, Paragraph 1, Item 4 as it existed before a 2002 amendment, often referred to as "old Item 4"). They alleged that several expenditures made on May 31, 1982, from the water enterprise budget, ostensibly for "conference and entertainment expenses" paid to various restaurants, were illegal. The residents claimed these conferences and entertainment events never actually took place and were merely fabricated to justify the payments. They sued on behalf of Osaka Prefecture, seeking to recover damages from the Manager (Y1) and the subordinate officials (Y2, Y3, and Y4) who were in positions of authority at the time.

Lower Courts: The "Hands and Feet" Theory of Managerial Liability

The path through the lower courts revealed a common but contested approach to liability in such cases:

- The Osaka District Court (First Instance) took a split approach.

- It dismissed the claims against the subordinate officials Y2, Y3, and Y4. The court reasoned that only the Manager (Y1) possessed the ultimate legal authority for such expenditures. Since authority had not been formally delegated (which would transfer authority), these subordinates did not qualify as "the said official" (tōgai shokuin) who could be held personally liable under old Item 4 of the Local Autonomy Act.

- However, the District Court found in favor of the residents regarding the Manager Y1, holding him partially liable. It determined that the expenditures were indeed illegal. Crucially, it applied what is known as the "auxiliary official as limbs" theory (hojo shokuin teashi ron, literally "auxiliary official as hands and feet" theory). Under this theory, even though the General Affairs Section Chief (Y4, Mr. Okazaki) had made the actual senketsu approval for these specific expenditures, he was merely acting as the "hands and feet" of the Manager Y1. Y1, retaining ultimate authority, was deemed to have simply used Y4 for the "auxiliary execution" of his own spending power. The court also found that Y1 was aware of the illegality of these expenditures.

- The Osaka High Court (Appeal Court) upheld the District Court's judgment, dismissing appeals from both the Manager Y1 and the resident plaintiffs X et al.

Dissatisfied, both Y1 (the Manager) and X et al. (the residents) appealed to the Supreme Court. Y1's appeal became Case ①, and X et al.'s appeal became Case ②.

The Supreme Court's Twin Decisions: Refining Liability in Senketsu Cases

On December 20, 1991, the Supreme Court issued two distinct but related judgments that significantly refined the understanding of liability in senketsu cases, moving away from the "hands and feet" theory.

Defining "The Said Official" (tōgai shokuin)

Both judgments referenced a 1987 Supreme Court precedent which had broadly defined "the said official" liable under old Item 4. This definition included:

- Those who statutorily and originally possess the authority for the financial or accounting act in question.

- Those who have acquired such authority through means such as delegation of authority from the original holder.

The 1991 decisions applied and elaborated on this definition in the context of senketsu.

Case ① (Manager Y1's Appeal): The Manager's Liability – Grounded in Supervisory Duty

The Supreme Court overturned the High Court's decision regarding Y1's liability and remanded this part of the case.

- Manager as "The Said Official": The Court affirmed that the Manager of a local public enterprise does qualify as "the said official." This is because the Manager statutorily and originally holds the authority for financial and accounting acts of the enterprise, even if internal rules allow for senketsu by subordinates for certain matters.

- Rationale: The Court explained that while senketsu does not formally transfer the Manager's statutory authority to the subordinate, internally the authority to make that specific decision is entrusted to the subordinate, who is expected to exercise their own judgment. Therefore, if the subordinate's senketsu decision is illegal and causes damage, the primary responsibility for that decision lies with the subordinate who made it. The Manager should not be automatically liable for the subordinate's act unless a failure in the Manager's own duty of command and supervision can be established.

Limited Liability for Senketsu Acts: However, the Supreme Court crucially departed from the lower courts' "hands and feet" reasoning for holding the Manager liable. It ruled that when an auxiliary official, duly entrusted with senketsu power, makes a decision that leads to an illegal financial act:

The Manager is liable for damages to the local public entity only if the Manager breached their duty of command and supervision and, through intent or negligence, failed to prevent the auxiliary official from committing the illegal financial or accounting act.

Case ② (Residents X et al.'s Appeal): Subordinate Officials' Liability – Those with Senketsu Power ARE Liable

The Supreme Court partially overturned the lower court decision that had dismissed claims against the subordinate officials and remanded this aspect.

- Auxiliary Officials with Senketsu Power as "The Said Official": The Court held that "the said official" under old Item 4 also includes auxiliary officials who, under clear internal administrative rules (like directives providing for senketsu), have been pre-authorized by the person holding statutory authority to make decisions via senketsu regarding specific financial/accounting acts. These officials are thus responsible for the decision-making pertaining to that authority.

- Rationale: This is because senketsu, when properly established by internal rules, is a legitimate and regular method of internal administrative processing. An official entrusted with senketsu authority is not, as the 1987 precedent clarified for an official with no financial role (the Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly President in that case), someone entirely unrelated to the financial or accounting authority in question. They are, in fact, the designated internal decision-maker for those specific matters.

Unpacking the Rulings: Implications for Public Accountability

These twin Supreme Court decisions significantly clarified the lines of responsibility within public administration when decisions are made through the senketsu system.

Rejecting the "Hands and Feet" Doctrine:

The most significant impact was the rejection of the "auxiliary official as limbs" theory. This theory, while perhaps offering a straightforward way to hold the top official accountable, did not accurately reflect the internal distribution of decision-making power under a formal senketsu arrangement and potentially shielded the actual decision-maker (the subordinate with senketsu power) from direct liability in a residents' lawsuit.

The Rationale: Personal Responsibility in Decision-Making:

The Supreme Court's approach emphasizes that liability should, in the first instance, attach to the individual who actually makes the decision based on their own judgment, especially when that judgment is exercised under a recognized internal procedure like senketsu.

- For the Subordinate Official: If they are duly authorized to make a decision via senketsu, they are exercising a form of entrusted authority and are accountable for the legality of that decision. They are not merely acting as a conduit for the manager's will but are expected to apply their own judgment within the scope of their senketsu power.

- For the Manager: The Manager retains overall responsibility as the original holder of the statutory authority. However, for actions taken by subordinates under senketsu, the Manager's liability shifts from direct responsibility for the act itself to responsibility for proper command and supervision of those subordinates. The Manager is liable if they failed in this supervisory duty, and that failure led to the illegal act.

This approach had been foreshadowed by some lower court decisions that had focused on the manager's supervisory responsibility rather than direct imputation of the subordinate's act. The Supreme Court's 1991 rulings brought uniformity to this area of law. Most legal scholars subsequently supported this position, reasoning that residents' lawsuits aim to establish the personal liability of the officials who actually committed or were responsible for the illegal financial acts, rather than a broader organizational liability.

Relevance Under Current Local Autonomy Act:

It's important to note that old Item 4 of Article 242-2(1) of the Local Autonomy Act, under which this case was brought, has since been amended (in 2002). The current version frames a residents' lawsuit for damages as one where residents demand that the "executive organ or official" (e.g., the current mayor or governor) sue "the said official" (the one who caused the damage) to recover losses on behalf of the local government. If the executive organ fails to file such a suit, the residents can then proceed with the lawsuit themselves, effectively compelling the local government to exercise its claim against the responsible official(s).

Under this current framework, the question of who qualifies as "the said official" directly translates to identifying who bears the substantive financial liability that the local government should seek to recover. The principles established in the 1991 Supreme Court decisions regarding senketsu—that the senketsu-authorized subordinate is a primary decision-maker and the manager is liable for supervisory failures—remain highly relevant in determining who these responsible individuals are. Legal commentary on a 2021 Nagoya High Court case (involving a Prefectural Police Chief's senketsu decision for officer deployment) indicates these principles continue to inform judicial reasoning.

Conclusion: Clarifying Lines of Responsibility in Delegated Decision-Making

The Supreme Court's 1991 judgments in the Osaka Waterworks cases brought much-needed clarity to the allocation of responsibility for financial acts performed under the senketsu system. By moving beyond the simplistic "hands and feet" theory, the Court established a more nuanced framework that recognizes the decision-making role of subordinate officials entrusted with senketsu powers, making them directly accountable as "the said official" in residents' lawsuits. Simultaneously, it defined the manager's liability not as automatic vicarious liability but as one based on their crucial duty of command and supervision. These rulings underscore the importance of personal accountability at all levels of public administration where financial decisions are made, even within established internal authorization structures.