Defying the Court: Japanese Supreme Court on the Validity of Shares Issued Despite an Injunction

Judgment Date: December 16, 1993

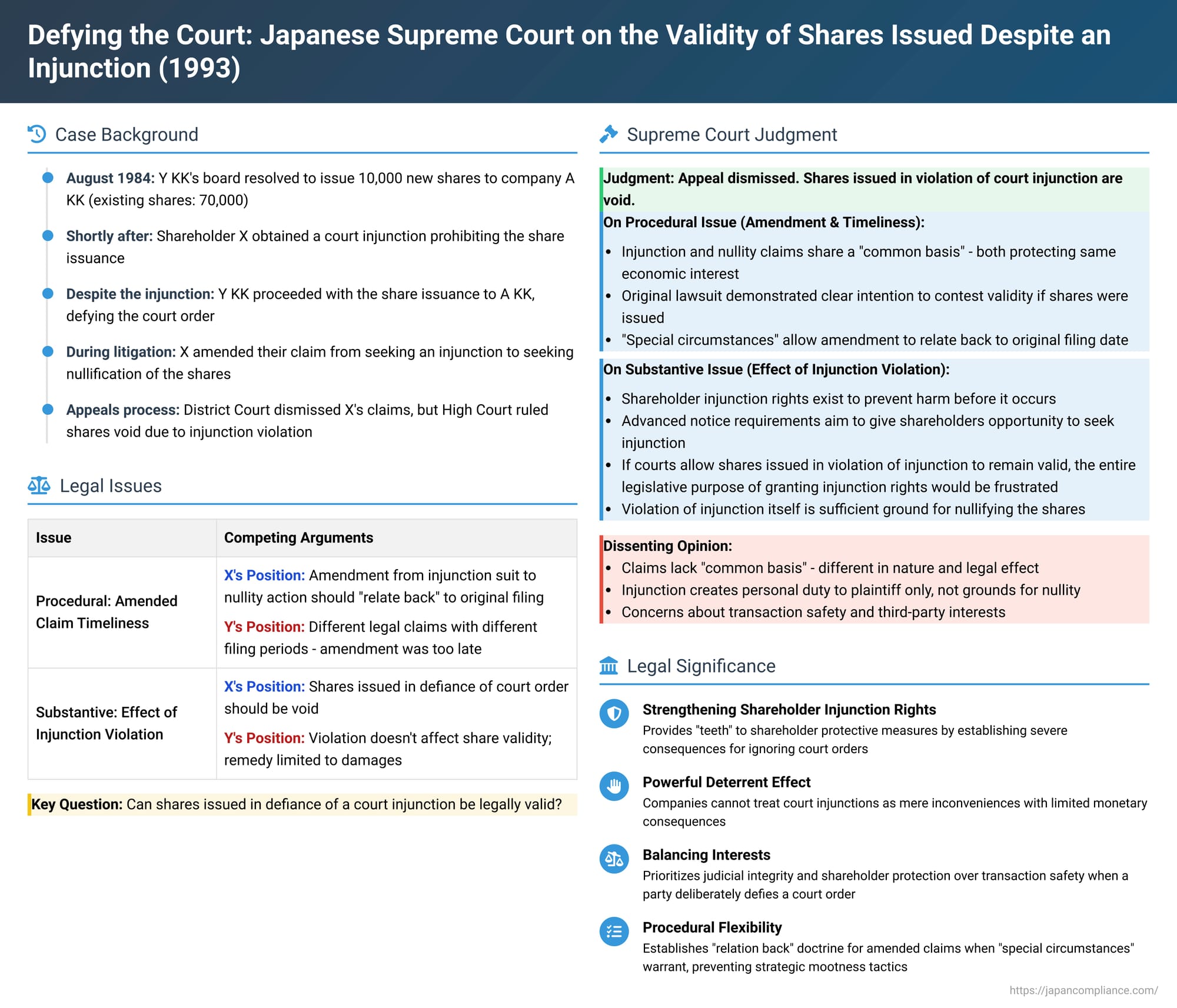

When a company plans to issue new shares, existing shareholders who believe the issuance is unlawful or grossly unfair have the right to seek a court injunction to prevent it. But what happens if a company, despite being served with such a court order, proceeds with the share issuance anyway? Are those shares valid? And can shareholders who initially sought to stop the issuance then challenge the validity of the already-issued shares, even if the statutory deadline for such a challenge seems to have passed? A 1993 Supreme Court of Japan decision tackled these critical questions, delivering a landmark ruling on the consequences of issuing shares in defiance of a court injunction.

The Disputed Share Issuance and the Injunction

The case involved Y KK, a company whose articles of incorporation included restrictions on the transfer of its shares (making it a "non-public company" in the sense of requiring board approval for share transfers). At the time, Y KK had 70,000 issued shares. On August 23, 1984, Y KK's board of directors passed a resolution to issue 10,000 new shares via a third-party allotment to another company, A KK.

X, a shareholder of Y KK, along with other shareholders, opposed this new share issuance. They alleged that its primary purpose was to dilute the shareholding percentage of shareholders who were critical of the current management's policies, thereby allowing management to solidify its control over Y KK. They argued this was a grossly unfair method of issuing shares and would be detrimental to their interests as shareholders.

Acting on these concerns, X swiftly applied to the court and successfully obtained a provisional disposition (an interim injunction) prohibiting Y KK from proceeding with the new share issuance. Following this, X and fellow dissenting shareholders filed a formal lawsuit seeking a permanent injunction against the share issuance, citing violations of the then-Commercial Code (specifically, Article 280-2, Paragraph 2, regarding grossly unfair methods of share issuance).

Despite the clear court order prohibiting the issuance, Y KK chose to defy it. While Y KK did file an objection to the provisional disposition, it proceeded with the new share issuance as planned. A KK paid the subscription money for the new shares on the designated payment date, and the shares were issued.

The Procedural Saga: From Injunction Suit to Nullity Claim

The lawsuit for a permanent injunction continued for over a year. During the eighth oral hearing in that proceeding, Y KK's representatives presented a new argument: since the new shares had already been issued and the subscription money paid, X's claim for an injunction against the issuance was now moot – there was no longer any future act to enjoin, and thus X lacked the necessary legal interest to continue that specific claim.

Faced with this development, X et al. adapted their legal strategy:

- They maintained that a share issuance conducted in violation of a court injunction should be considered void from the outset.

- However, as a precautionary (or alternative) measure, they formally applied to the court to amend their existing lawsuit. They sought to change their claim from one seeking an injunction against the share issuance to one seeking a declaration of nullity of the already-issued shares, based on then-Commercial Code Article 280-15 (the provision for a new share issuance nullity action, now found in Article 828, Paragraph 1, Item 2 of the Companies Act).

- The grounds for this nullity claim were largely identical to those they had asserted for the injunction (e.g., grossly unfair method aimed at improper management control), with the crucial addition of the violation of the court's provisional disposition as a specific ground for nullity.

The Court of First Instance (Kyoto District Court) dismissed X's claims. However, the Appellate Court (Osaka High Court) took a different view:

- It agreed that the original claim for an injunction was now moot and dismissed it.

- Crucially, it allowed X's amendment to a nullity claim, deeming the amendment to have been timely filed by "relating back" to the date of the original injunction lawsuit filing.

- On the merits, the Appellate Court ruled that the new share issuance was void precisely because it had been carried out in violation of the provisional disposition.

Y KK, the issuing company, appealed this adverse decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated December 16, 1993, dismissed Y KK's appeal, thereby upholding the Osaka High Court's ruling that the shares issued in defiance of the injunction were void. The Supreme Court's decision addressed two main points: the procedural issue of amending the lawsuit and the substantive issue of the injunction violation's effect.

1. Amendment of Claim and Timeliness (The "Relation Back" Doctrine)

The Supreme Court first affirmed the High Court's decision to allow the amendment of X's claim from an injunction request to a nullity action, and to consider it timely filed.

- Common Basis of Claim: The Court reasoned that both the original injunction claim and the amended nullity claim shared a "common basis." Both actions were initiated by shareholders (X et al.) who alleged they would suffer detriment from the new share issuance and sought to either prevent it or negate its effect. They were, in essence, pursuing the "same economic interest." Furthermore, the evidence and legal arguments relevant to the injunction claim would largely be applicable to the nullity claim.

- "Special Circumstances" Justifying Relation Back: Generally, when a lawsuit is amended to introduce a new claim that is subject to a statutory filing period (like the nullity action, which typically had to be filed within six months of the share issuance under the old Code), compliance with that period is judged as of the date of the amendment. However, the Supreme Court recognized an exception: if "special circumstances" exist that allow the newly amended claim to be treated as if it had been filed at the time of the original lawsuit, the statutory filing period is deemed to have been met.

- In this case, X had first obtained a provisional disposition and then promptly filed the main lawsuit to enjoin the share issuance. The Supreme Court found that these actions clearly demonstrated X's intention to contest the validity of the new shares if they were issued in defiance of the court order, specifically citing the injunction violation as a ground. These actions constituted the "special circumstances" necessary to allow the nullity claim, introduced by amendment, to "relate back" to the filing date of the original injunction suit, thus satisfying the timeliness requirement for the nullity action.

2. Violation of an Injunction as a Ground for Share Issuance Nullity

This was the core substantive issue. The Supreme Court held:

If new shares are issued in deliberate violation of a provisional disposition (injunction) – where that injunction was based on a pending lawsuit seeking to enjoin that specific share issuance under the authority of then-Commercial Code Article 280-10 (now Companies Act Article 210) – then this violation of the injunction, by itself, constitutes a valid ground for nullifying the new share issuance in a subsequent nullity action (under then-Commercial Code Article 280-15, now Companies Act Article 828, Paragraph 1, Item 2).

The Court's reasoning for this crucial holding was:

- Purpose of the Shareholder's Injunction Right: The statutory right for shareholders to seek an injunction against improper new share issuances (e.g., those violating laws/articles of incorporation or conducted by grossly unfair methods) is specifically designed to protect shareholder interests by preventing such harm before it occurs.

- Purpose of Advance Notice Requirements: The legal requirement for companies to provide advance public notice or notice to shareholders regarding a planned new share issuance (under then-Commercial Code Article 280-3-2, which for public companies mandated notice two weeks before the payment date) is intended to give shareholders a meaningful opportunity to seek and obtain such a provisional disposition (injunction) if grounds exist. This notice provision thus aims to ensure the practical effectiveness of the shareholder's injunction right.

- Upholding Legislative Intent: If a company could issue shares in direct violation of such a court-ordered injunction, and if that violation had no bearing on the ultimate validity of the issued shares, then the entire legislative purpose of granting shareholders an effective right to stop improper issuances would be "nullified" or "frustrated" (mokkyaku sarete shimau). The injunction remedy would become toothless.

Therefore, to ensure the efficacy of this shareholder protection mechanism, the act of defying the injunction itself becomes a serious legal flaw tainting the share issuance.

The Dissenting View

It's important to note that the decision was not unanimous; there was a strong dissenting opinion (from Justices Ohori and Miyoshi). The dissent argued:

- No "Relation Back": The injunction claim (seen as an individual shareholder's personal right to prevent harm to themselves) and the nullity action (a corporate organizational lawsuit aimed at uniformly invalidating the shares for all, based on objective legal flaws) are fundamentally different in nature, legal standing requirements, causes of action, and the effect of their judgments. Therefore, they lack the "common basis" required for the nullity claim to relate back to the injunction suit's filing date for timeliness.

- Injunction Violation Not a Nullity Ground: An injunction, in the dissent's view, merely imposes a duty of non-action on the company vis-à-vis the specific plaintiff shareholder who obtained the injunction. It does not strip the company of its inherent legal power or authority to issue shares. A violation might give rise to a damages claim for that specific shareholder against the company or its directors, but it should not invalidate the shares themselves, particularly considering the need for transaction safety and the potential impact on innocent third-party acquirers of those shares. The grounds for nullifying a share issuance are generally limited to severe defects in the issuance process itself, and a mere violation of a personal injunction against one shareholder doesn't rise to that level. The dissent also worried that the majority's view would give excessive power to a provisional (interim) court order and could lead to unfair consequences if other shareholders or corporate officers (directors, auditors), who were not party to the original injunction, could later use that injunction's violation as a ground to nullify the shares.

Analysis and Implications

This 1993 Supreme Court decision has had a significant impact on Japanese corporate law and practice:

- Strengthening Shareholder Injunction Rights: The primary effect of the ruling is to substantially bolster the effectiveness of pre-issuance injunctions obtained by shareholders. Companies are now on clear notice that deliberately flouting such a court order carries the severe risk of the entire share issuance being declared void.

- Deterrent Effect: The decision acts as a strong deterrent against companies attempting to bypass or ignore judicial orders related to share issuances. The potential for nullification provides a much more potent sanction than, for example, mere monetary fines or damages claims against directors, which might have been seen as a "cost of doing business" in some aggressive control contests.

- Balancing Shareholder Protection and Transaction Safety: The majority opinion prioritized the efficacy of judicial process and the protection of shareholder rights (specifically, the right to seek a pre-emptive injunction) over concerns about absolute transaction safety in the context of a deliberate defiance of a court order. The reasoning implies that a party (the company) that knowingly violates an injunction cannot then easily claim the protection of "transaction safety" for the results of that violation.

- Procedural Flexibility ("Relation Back"): The Court's willingness to allow the "relation back" of the nullity claim under "special circumstances" also demonstrates a degree of procedural flexibility aimed at achieving substantive justice, preventing a company from benefiting from its own delay tactics or its act of rendering an injunction suit moot by proceeding with the issuance.

- Context of Non-Public vs. Public Companies:

- Y KK was a "non-public company" with share transfer restrictions. For such companies, the Companies Act (and its predecessor, the Commercial Code, especially after later amendments) imposes stringent requirements for third-party share allotments, typically requiring a special shareholder resolution (unless the articles provide otherwise for shareholder pre-emptive rights). A failure to adhere to these fundamental shareholder approval processes is itself a serious flaw and a strong ground for nullity. The Supreme Court's ruling in this case, therefore, aligns with the generally strong protections afforded to shareholders in non-public companies regarding new share issuances.

- For public companies, while the board generally has more authority to decide on share issuances (unless at a specially favorable price), the requirement to provide advance notice to shareholders to enable them to seek injunctions remains. The underlying logic of the Supreme Court – that the injunction system must be effective – would seem to apply here as well. Legal commentators suggest that this decision signals the Supreme Court's preference for resolving disputes about the legality of share issuances before the shares are issued and enter the market, through the injunction process.

Conclusion

The December 16, 1993, Supreme Court decision delivered a clear and forceful message: Japanese courts will not tolerate the deliberate defiance of injunctions issued to prevent potentially unlawful or unfair new share issuances. Such a violation, in itself, can serve as a ground for the subsequent nullification of those shares. Furthermore, the ruling demonstrated a willingness to apply procedural rules like the amendment of claims and the "relation back" doctrine flexibly to ensure that shareholders who diligently seek to protect their rights through judicial means are not unfairly disadvantaged by a company's attempts to circumvent court orders. This case remains a vital precedent in upholding the integrity of judicial processes and the statutory rights of shareholders in the context of corporate finance and governance.