Defining "Worker" for Collective Bargaining: Insights from Japan's Supreme Court in the "Customer Engineer" Case

Judgment Date: April 12, 2011

Case Name: Claim for Revocation of an Unfair Labor Practice Remedy Order (Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench)

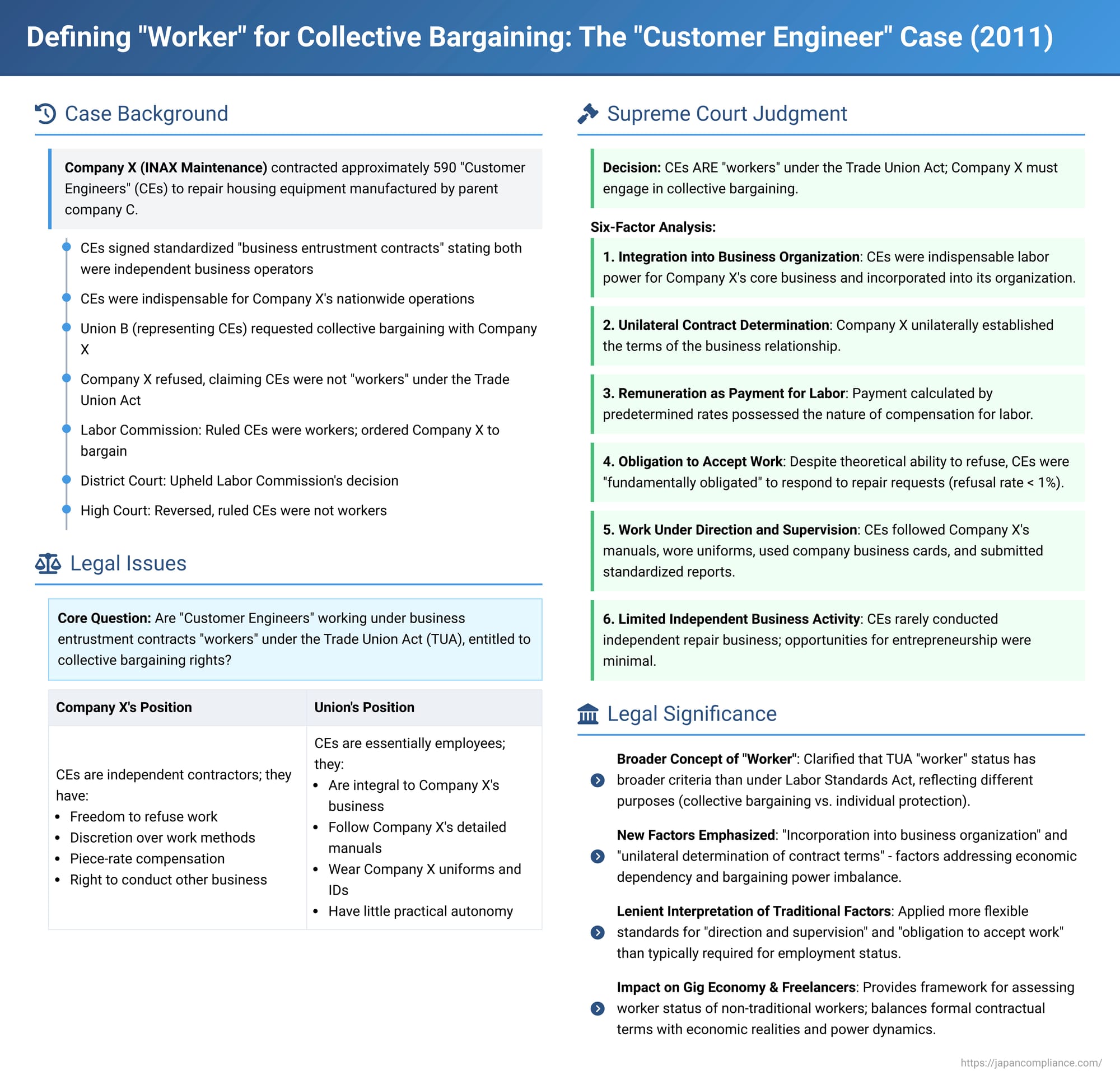

The scope of who qualifies as a "worker" entitled to collective bargaining rights under Japan's Trade Union Act (TUA) is a critical issue, particularly with the diversification of work arrangements. A landmark Supreme Court judgment issued on April 12, 2011, often referred to as the INAX Maintenance case in legal commentaries (though we will refer to the company as "Company X" and its parent as "Company C" for anonymity), provides significant clarification on this matter. This ruling distinguished the criteria for determining "worker" status under the TUA from those under the Labor Standards Act (LSA), suggesting a broader interpretation for collective labor relations.

Factual Background of the Dispute

Company X's primary business was the repair and maintenance of housing equipment manufactured by its parent company, Company C. The bulk of this repair and maintenance work was not performed by Company X's direct employees but by approximately 590 "Customer Engineers" (CEs). These CEs operated under "business entrustment contracts" (業務委託契約 - gyōmu itaku keiyaku) with Company X, which stipulated that both parties were independent business operators.

Despite these contractual terms, the operational reality of the CEs was nuanced:

- Company X's Reliance on CEs: Only a very small fraction of Company X's direct employees (around 200 in total, primarily Service Managers and highly skilled Technical Specialists FG) were capable of performing the actual repair work. Thus, the CEs were indispensable for Company X's core business operations nationwide.

- Contractual Framework:

- CEs entered into a standardized "Memorandum Concerning Business Entrustment" drafted by Company X. This agreement defined the scope of work (after-sales service for Company C products, inspections, sales, installations, etc.).

- Company X implemented a "CE license system," determining a CE's rank annually based on ability, performance, and experience, to maintain Company C's brand image and service quality.

- Contracts were for one year and renewable, but Company X could refuse renewal if it had objections.

- Work Assignment and Control:

- Company X assigned CEs to specific territories, often based on their residence.

- Company X, in consultation with CEs, designated their workdays and holidays, and requested CEs to cover Sundays and public holidays on a rotational basis.

- Repair requests from customers were received by Company X's call centers and then assigned to the CE responsible for the customer's area.

- Requests were typically transmitted to a data terminal that CEs were required to carry, between 8:30 AM and 7:00 PM on workdays.

- CEs were expected to perform the requested work promptly. The rate of refusal by CEs upon receiving a data-transmitted request was less than 1%. While Company X apparently did not treat refusals as breaches of contract, the context of annual contract renewals and rank evaluations likely influenced acceptance rates.

- CEs were required to wear Company X's uniform and carry its business cards, which identified them with a specific service center of Company X, to signify that the work was being done by a subsidiary of Company C.

- Company X provided CEs with various manuals detailing work procedures, reporting methods, customer service standards, and even the expected mindset and role of a CE, to ensure nationwide service quality and protect Company C's brand image. CEs were expected to follow these manuals.

- CEs had to submit service reports to Company X in a prescribed format upon completion of work and report their daily activities (schedules, progress, results).

- Remuneration:

- CEs' remuneration was calculated by multiplying the customer billing amount (predetermined by Company X for specific products and repair types) by a rate corresponding to the CE's rank. Additional payments, equivalent to overtime allowances, were made for work outside normal hours or on holidays, and travel allowances were also paid.

- While CEs could, to some extent, charge more for complex jobs or when using an assistant (a practice also allowed for Company X's employee technicians), the base rates were set by Company X.

- Limited Independent Entrepreneurial Activity:

- Although the High Court had suggested CEs could conduct their own business, the Supreme Court noted that, on average, CEs had little time for independent business activities. Data showed that instances of CEs independently contracting for and performing repairs were rare.

- A supplementary opinion by one of the Supreme Court justices highlighted that Company X's recruitment advertisements for CEs used language typical of employment offers (mentioning "work location," "working hours," "salary," "benefits," "holidays/leave"). Furthermore, a "CE License System" document described "welfare and meritorious benefits" such as health check-ups, congratulatory/condolence payments, "refresh leave allowances," and bereavement leave – terms incongruous with a typical independent contractor relationship. Until around 2002, CE ID cards issued by Company X even stated, "This certifies that the above person is an employee of our company," before being changed to reflect an entrustment relationship.

The Labor Dispute and Procedural History

The Unions B, which the CEs had joined, requested collective bargaining with Company X on several issues, including changes to working conditions, remuneration (e.g., guaranteed minimum annual income of 5.5 million yen), payment of allowances, Company X bearing costs for loaned equipment, and enrollment of all CEs in workers' accident compensation insurance.

Company X refused to bargain, asserting that the CEs were independent business operators and not "workers" under the TUA, thus Company X had no obligation to engage in collective bargaining with their union.

The Unions B filed an unfair labor practice complaint with the Osaka Prefectural Labor Commission. The Commission found that the CEs were indeed TUA workers and that Company X's refusal to bargain constituted an unfair labor practice. It ordered Company X to bargain. This decision was upheld by the Central Labor Commission upon review.

Company X then sued to revoke the Central Labor Commission's order.

- The District Court (Tokyo District Court): Ruled against Company X, affirming the CEs' TUA worker status.

- The High Court (Tokyo High Court): Overturned the District Court's decision. It found the CEs not to be TUA workers, emphasizing their freedom to refuse individual assignments, their discretion over how and when to perform tasks, the absence of direct, specific supervision from Company X, their piece-rate remuneration, and the allowance for them to undertake independent business activities. The High Court viewed them essentially as outsourced contractors.

The case then proceeded to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court, in its decision on April 12, 2011, overturned the High Court's ruling and affirmed the CEs' status as workers under the Trade Union Act. The Court engaged in a comprehensive assessment of various factors, concluding that the CEs were indeed TUA workers in their relationship with Company X. The key elements of the Court's reasoning were:

- Integration into Company X's Business Organization: The Court noted that CEs performed the core repair operations essential to Company X's business, as Company X's own employees capable of such work were very few. CEs were managed under license and ranking systems and assigned to specific territories to provide daily repair services. Company X also coordinated their workdays and holidays, including coverage for Sundays and public holidays. This led the Court to conclude that CEs were "indispensable labor power for the pursuit of X's said business and incorporated into X's organization for its constant securing."

- Unilateral Determination of Contract Terms by Company X: The content of the business entrustment contract between Company X and the CEs was governed by the "Memorandum Concerning Business Entrustment" established by Company X. The Court found it clear that CEs had no room to alter the content of individual repair requests. Therefore, Company X unilaterally determined the contractual terms with the CEs.

- Remuneration as Payment for Labor Provided: The CEs' pay was calculated based on customer billing amounts predetermined by Company X according to the product and type of repair, multiplied by a rate set by Company X for the CE's specific rank, with additions equivalent to overtime pay. The Court deemed this to possess the nature of remuneration for the provision of labor.

- CEs' General Obligation to Accept Work Requests: CEs were expected to perform repair work immediately upon request. The refusal rate for assignments sent via data terminal (the primary method) was extremely low (under 1%). Considering that the contracts were for one year and subject to non-renewal if Company X objected, and that CE remuneration and assigned territories were determined by Company X, the Court found that "in terms of the parties' understanding and the actual operation of the contract, it is appropriate to view the CEs as being in a relationship where they were fundamentally obligated to respond to individual repair requests from X," even if they were not held liable for breach of contract for refusing. This indicated a lack of substantial freedom to refuse work.

- Provision of Labor under Company X's Direction and Supervision, with Time and Place Constraints: CEs performed repairs at customer locations within territories designated by Company X. They were generally expected to be available for dispatch communications from 8:30 AM to 7:00 PM on workdays. They wore Company X's uniforms, carried its business cards, submitted standardized service reports, and were required to follow various detailed manuals (covering procedures, reporting, mindset, customer service) provided by Company X to maintain brand image and service quality. The Court concluded from these facts that CEs "provided labor according to the work performance methods specified by X and under its direction and supervision, and were also subject to certain constraints regarding the place and time of their work."

- Difficulty and Rarity of CEs Engaging in Independent Entrepreneurial Activity: The Supreme Court discounted the High Court's emphasis on the CEs' theoretical ability to engage in their own business. It found that the average CE likely had limited time for such activities, and there was little evidence of CEs operating as independent repair businesses. Such "exceptional instances" should not be overemphasized.

Overall Conclusion on Worker Status and Duty to Bargain:

Based on a comprehensive consideration of all these circumstances, the Supreme Court concluded that the CEs qualified as workers under the Trade Union Act in their relationship with Company X.

Having established their TUA worker status, the Court further determined that the topics for which the Unions B had requested collective bargaining (such as working conditions, remuneration, and the operation of collective labor relations) were matters that Company X had the authority to decide. Therefore, Company X's refusal to bargain with the Unions B, on the grounds that CEs were not TUA workers, constituted an unfair labor practice under Article 7, Item 2 of the TUA. The Supreme Court thus upheld the Central Labor Commission's remedy order.

Analysis and Significance of the Judgment

This Supreme Court ruling, along with two other contemporaneous decisions (the Shin National Theatre Foundation case and the Victor Service Engineering case), significantly advanced the understanding of "worker" status under the Trade Union Act.

- A Broader Concept of "Worker" for TUA Purposes:

A key takeaway is the Court's implicit confirmation that the criteria for determining "worker" status under the TUA are not identical to, and are potentially broader than, those for "worker" status under the Labor Standards Act (LSA). The LSA primarily focuses on individual worker protection through direct employment regulations, often emphasizing "subordination to direction and supervision" in a fairly strict sense. The TUA, on the other hand, aims to protect workers' rights to organize and bargain collectively to improve their working conditions, suggesting the need for a concept of "worker" that reflects bargaining power imbalances. - Emphasis on New or Differently Weighted Factors:

The Supreme Court highlighted factors not traditionally central to LSA worker status determinations, or at least gave them different weight:- Incorporation into the Principal's Business Organization (Factor 1): The Court strongly emphasized how essential CEs were to Company X's core operations and how they were integrated into its organizational structure for delivering services. This factor looks beyond direct, moment-to-moment supervision to the functional role of the individual within the business.

- Unilateral Determination of Contract Terms (Factor 2): The Court pointed to Company X's power to set the terms of the contract and work requests. This addresses the disparity in bargaining power, a core concern of the TUA.

These factors are less prominent in typical LSA analyses.

- More Lenient Interpretation of Traditional Factors:

For factors that are common to LSA analysis, such as the freedom to refuse work (Factor 4) and subjection to direction/supervision and time/place constraints (Factor 5), the Supreme Court appeared to apply a more relaxed standard in the TUA context. For instance, even if CEs were not formally penalized for refusing a specific job, the overall contractual context (annual renewals, ranking system) led to a finding that they were "fundamentally obligated" to accept. Similarly, the constraints and adherence to manuals were deemed sufficient for "direction and supervision" and "time/place constraints" in the TUA sense, even if they didn't amount to the minute control sometimes expected for LSA employee status. - Departure from Stricter Lower Court Approaches:

Prior to this series of Supreme Court judgments, some lower courts had increasingly denied TUA worker status by rigidly applying LSA-like criteria, focusing heavily on the absence of formal, legal subordination. This judgment signaled a shift away from that restrictive trend for TUA purposes. - Impact on Subsequent Guidelines and Cases:

This ruling has influenced subsequent legal discourse. A 2011 report by the Labor Relations Law Study Group, for instance, organized the TUA worker status judgment factors, identifying "incorporation into business organization," "unilateral contract determination," and "remuneration as labor-exchange value" as basic elements, with others as supplementary or negative factors. Labor commissions and lower courts have generally followed the Supreme Court's approach in subsequent cases. However, debates continue, particularly in complex arrangements like franchise agreements for convenience store owners. - Ongoing Academic Discussion:

The judgment aligns with academic views that advocate for a broader conception of TUA worker status, often emphasizing "economic dependency" alongside a more flexible understanding of "personal/organizational dependency." However, the Supreme Court did not explicitly adopt any specific academic theory or provide a definitive, abstract framework, leaving the decision as a comprehensive, fact-intensive assessment. Some scholars also critique the approach of determining TUA worker status based on the relationship with a specific counterparty, arguing for a broader understanding of who can be a bearer of collective action rights. - Interaction with Antitrust Law:

If individuals with entrepreneurial characteristics (like some CEs) are deemed TUA workers, it raises questions about the intersection of labor law and antimonopoly law. Japan's Antimonopoly Act (AMA) regulates "entrepreneurs" and prohibits unfair trade restrictions. The TUA exempts legitimate union activities from AMA scrutiny. If TUA "workers" can also be AMA "entrepreneurs," a conflict can arise.

A 2018 report by a Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) research center suggested that activities governed by labor law generally do not pose AMA problems, but the AMA could apply in exceptional cases, such as when activities deviate from the spirit of labor legislation. Guidelines issued in 2021 by the Cabinet Secretariat and other bodies for freelancers echo this, but the precise boundaries remain a subject of discussion. - Implications for Freelancers and New Work Forms:

The principles from this judgment are applied to determine whether freelancers and individuals in other non-standard work arrangements qualify for TUA protections. If TUA worker status is denied, the question of how to provide collective protection becomes critical. Current Japanese law offers some avenues, such as forming cooperatives under the Small and Medium-sized Enterprise, etc. Cooperatives Act, which can conclude collective agreements. However, expanding TUA protections to cover a broader range of dependent self-employed individuals remains a topic of ongoing policy debate.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's April 12, 2011, judgment in the "Customer Engineer" case is a vital precedent in Japanese collective labor law. It affirmed that the assessment of "worker" status under the Trade Union Act involves a comprehensive evaluation of the actual working relationship, employing a potentially broader set of criteria than that used for the Labor Standards Act. By considering factors like deep integration into the principal's business operations and the unilateral determination of contractual terms, alongside a more flexible view of supervision and work acceptance, the Court recognized the need to protect individuals who, despite formal contractual labels, are in a position of dependency that warrants access to collective bargaining rights. This decision continues to shape discussions on labor rights in an era of increasingly diverse and complex working arrangements.