Defining 'Trade Reality' in Trademark Similarity: The Hodogaya Chemical Case

Judgment Date: April 25, 1974

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Case Number: Showa 47 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 33 (Action for Rescission of a Trial Decision)

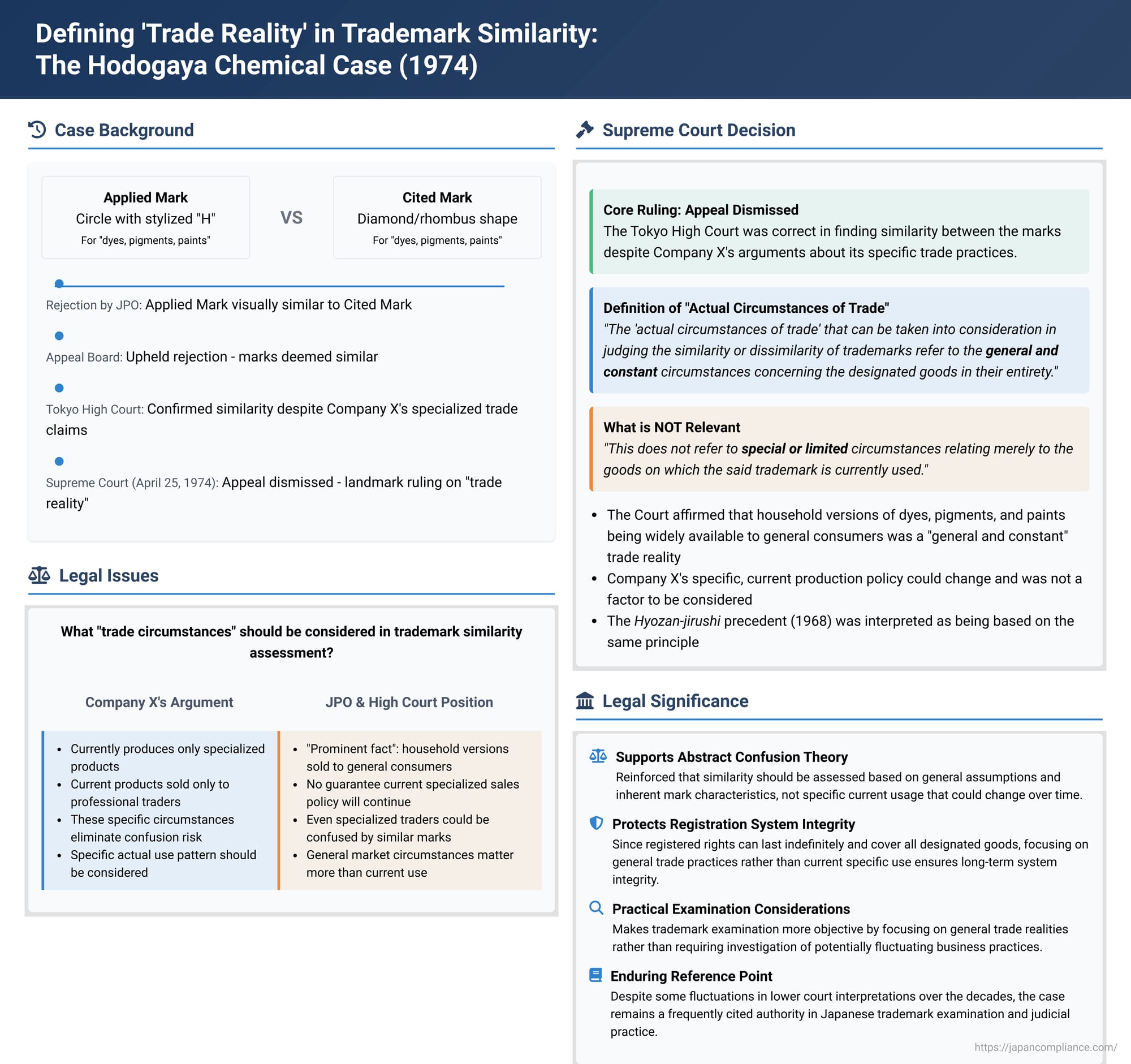

The "Hodogaya Chemical Co. Mark Case" (保土谷化学工業社標事件 - Hodogaya Kagaku Kōgyō Shahyō Jiken), decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 1974, is a critical judgment that refined the understanding of what constitutes "actual circumstances of trade" (取引の実情 - torihiki no jitsujō) when assessing trademark similarity during the ex parte registration process. This case clarified that for the purposes of determining registrability under Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 11 of the Trademark Law, consideration should be given to the general and constant trade realities concerning the entire scope of the designated goods, rather than specific, potentially transient, current uses of a mark by an applicant.

The Competing Marks and Initial Decisions

The appellant, Company X (legally Hodogaya Chemical Co., Ltd.), filed an application to register a device mark (a stylized 'H' within a circle, as depicted in the provided materials). The designated goods for this "Applied Mark" included "dyes, pigments, paints (excluding electrical insulating paints)," and other related products.

The Japan Patent Office (JPO) rejected Company X's application. The basis for rejection was the similarity of the Applied Mark to a prior registered device mark (the "Cited Mark," a stylized diamond/rhombus shape) under Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 11 of the Trademark Law. The Cited Mark was also registered for "dyes, pigments, paints (excluding electrical insulating paints)".

Company X appealed this rejection to the JPO appeal board, but the board upheld the examiner's decision. Subsequently, Company X initiated a lawsuit to overturn the JPO's decision. In this lawsuit, Company X put forth a significant argument based on its specific trade practices: it contended that for the designated goods (dyes, pigments, and paints), the typical traders involved were specialized professionals. Furthermore, Company X asserted that the dyes it was currently producing were not marketed or sold to general consumers. Based on these specific circumstances, Company X argued that despite any visual similarities between its Applied Mark and the Cited Mark, there was no actual likelihood of consumers being confused as to the source of the goods.

The Tokyo High Court, however, dismissed Company X's claim. The High Court found that the Applied Mark and the Cited Mark were indeed visually similar. In response to Company X's argument about its specialized trade channels, the High Court stated:

- It is a "prominent fact" that household versions of dyes, pigments, and paints are commonly sold to general consumers through various retail outlets like department stores, paint shops, and stationery stores.

- There was no evidence to suggest that Company X's current production and sales policy (i.e., not targeting general consumers) would necessarily continue indefinitely into the future.

- Even among specialized professional traders, the possibility of source confusion arising from the visual similarity of the marks could not be entirely discounted.

Company X then appealed this adverse High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Key Clarification on "Actual Circumstances of Trade"

The Supreme Court dismissed Company X's appeal, thereby affirming the decisions of the JPO and the Tokyo High Court. The core of the Supreme Court's judgment was its precise definition of the "actual circumstances of trade" that are relevant for assessing trademark similarity in the context of registration:

The Court declared: "The 'actual circumstances of trade' that can be taken into consideration in judging the similarity or dissimilarity of trademarks refer to the general and constant (一般的、恒常的 - ippanteki, kōjōteki) circumstances concerning the designated goods in their entirety."

It explicitly stated that this does not refer to "special or limited (特殊的、限定的 - tokushuteki, genteiteki) circumstances relating merely to the goods on which the said trademark is currently used."

The Supreme Court further clarified that its own influential precedent, the Hyozan-jirushi (Iceberg Mark) case (Supreme Court, 1968), which also discussed considering trade circumstances, should be understood as being based on this same premise.

Therefore, the Supreme Court found that the Tokyo High Court was correct in its approach. By taking into account the "prominent fact" that household versions of the designated goods (dyes, pigments, and paints) were widely available to and purchased by general consumers, the High Court was properly considering the general and constant trade circumstances for those goods. The Supreme Court deemed this approach "entirely justifiable".

Consequently, the Supreme Court held that the question of whether Company X's current specific production and sales policies (i.e., focusing only on specialized traders and not general consumers) would continue indefinitely was not a factor that should be considered when judging the similarity of the trademarks for registration purposes. Any comments by the High Court on this particular point were regarded as merely obiter dictum (incidental remarks not forming part of the essential reasoning).

Why This Limitation Matters for Trademark Registration

The Supreme Court's distinction between general/constant circumstances and specific/current-use circumstances is particularly important in the context of trademark registration for several reasons:

- Nature of Trademark Rights: Registered trademark rights can potentially last indefinitely through renewals. The owner is granted rights for the trademark in relation to all goods or services specified in the registration, not just those they are currently producing or marketing in a particular way. If similarity were judged solely on an applicant's narrow, current use, a mark might be registered that could later cause confusion if the owner expands their product line or changes their marketing strategy to target a broader audience within the scope of their registration.

- JPO's Ex Parte Examination Process: Trademark registration is initially an ex parte process (between the applicant and the JPO). The JPO examines applications based on the information provided and publicly available data. It would be impractical and administratively burdensome for the JPO to investigate and verify the specific, potentially fluctuating, current business practices of every applicant for every designated good or service. A focus on general and constant trade circumstances provides a more stable and objective basis for examination.

The "Abstract Confusion" vs. "Concrete Confusion" Debate

The Hodogaya Chemical ruling has significant implications for a long-standing theoretical debate in trademark law concerning how "likelihood of confusion" should be assessed. This debate generally revolves around two main viewpoints:

- Abstract Confusion Theory (抽象的混同説 - chūshōteki kondōsetsu): This approach posits that the likelihood of confusion should be assessed based on general trade assumptions and the inherent characteristics of the marks themselves, largely disregarding (or "abstracting away") the applicant's specific, current, and potentially changeable methods of use. A prominent version of this theory asks whether "the marks themselves are so similar that they are likely to be mistaken for each other". The rationale often involves the potential perpetuity of trademark rights and the fact that an owner's actual use of a mark can evolve over time. If marks are inherently confusable, future changes in use could easily lead to actual confusion, even if a specific, narrow current use does not.

- Concrete Confusion Theory (具体的混同説 - gutaiteki kondōsetsu): This theory argues for assessing the actual, concrete risk of confusion by taking into fuller account the specific circumstances of how the marks are, or would be, encountered in the marketplace. Proponents believe this provides a more realistic assessment of actual market impact. Some modern advocates of this view, while acknowledging the long-term nature of trademark rights, suggest that specific circumstances which are "expected to continue stably for a certain period" might be legitimately considered.

The Hodogaya Chemical decision, by emphasizing "general and constant" trade circumstances for the entire scope of designated goods and excluding "special or limited" current uses from the registrability assessment, clearly aligns with, and lends strong Supreme Court support to, the Abstract Confusion Theory in the context of ex parte trademark registration.

Post-Hodogaya Developments and Scholarly Perspectives

The Hodogaya Chemical ruling has been influential, yet the application of "trade circumstances" in assessing trademark similarity has seen some fluctuations in lower court decisions over the years.

- Initial Interpretation of Hyozan-jirushi: The Hyozan-jirushi case, a key precedent, established that trademark similarity is judged by the likelihood of confusion, necessitating consideration of how goods are transacted. That decision itself considered general trade practices for specialized goods (glass fiber yarn). However, some language in Hyozan-jirushi also suggested that "specific trade circumstances, insofar as they can be clarified," should be considered, which could be interpreted more broadly to include current usage details if known. The Hodogaya Chemical judgment explicitly narrowed this potential broad reading of Hyozan-jirushi for registration purposes, restricting "trade circumstances" to those that are general and constant.

- Fluctuations in Lower Court Practice: Despite the Hodogaya ruling, some subsequent Tokyo High Court decisions appeared to consider factors that might be viewed as specific or transient, such as an applicant's current labeling, advertising, or limited distribution channels, when finding marks dissimilar. This tendency drew criticism from legal scholars who saw it as a deviation from the Hodogaya principle. In the early 2000s, there was a period where courts more frequently cited Hodogaya to dismiss arguments based on such specific, current uses. However, around 2010, another series of IP High Court cases emerged that again seemed to place significant weight on the specific current use patterns of both the applied-for mark and the cited mark, even in registration appeal contexts. This, too, faced academic critique. More recently, there has been a noticeable trend back towards courts citing Hodogaya Chemical and rejecting reliance on specific, current use details as not constituting the "general and constant" trade circumstances required for the similarity assessment at the registration stage.

- The Search Cost Theory: Some legal scholars argue that the Hodogaya Chemical approach (and the Abstract Confusion Theory it supports) can also be justified by the "search cost theory" of trademark law. This theory posits that a primary function of trademark law is to reduce the "search costs" for consumers trying to find and differentiate products and services. If marks are inherently very similar, relying on external, potentially changeable factors (like current specific marketing practices) to distinguish them is undesirable because if those external factors change, consumer search costs increase, and confusion can result. Therefore, maintaining clear distinctions based on the inherent qualities of the marks, as assessed against general trade conditions, is preferable.

Conclusion

The Hodogaya Chemical Co. Mark case is a pivotal Supreme Court judgment that provides essential clarity on the scope of "actual circumstances of trade" to be considered when determining trademark similarity for the purposes of registration in Japan. By firmly stating that such circumstances must be "general and constant" for the entire range of designated goods, and not merely the applicant's specific, potentially temporary, current use, the Court endorsed a framework consistent with the Abstract Confusion Theory. This approach prioritizes the long-term integrity and clarity of the trademark register, ensuring that trademark rights are granted based on a stable and objective assessment of potential confusion in the broader marketplace anticipated by the scope of the application, rather than on potentially narrow or fluctuating current business strategies. This ruling continues to be a significant and frequently cited authority in Japanese trademark examination and judicial practice.