Japan’s Supreme Court Defines “First Consultation Date” for Disability Basic Pension Eligibility (2008)

TL;DR

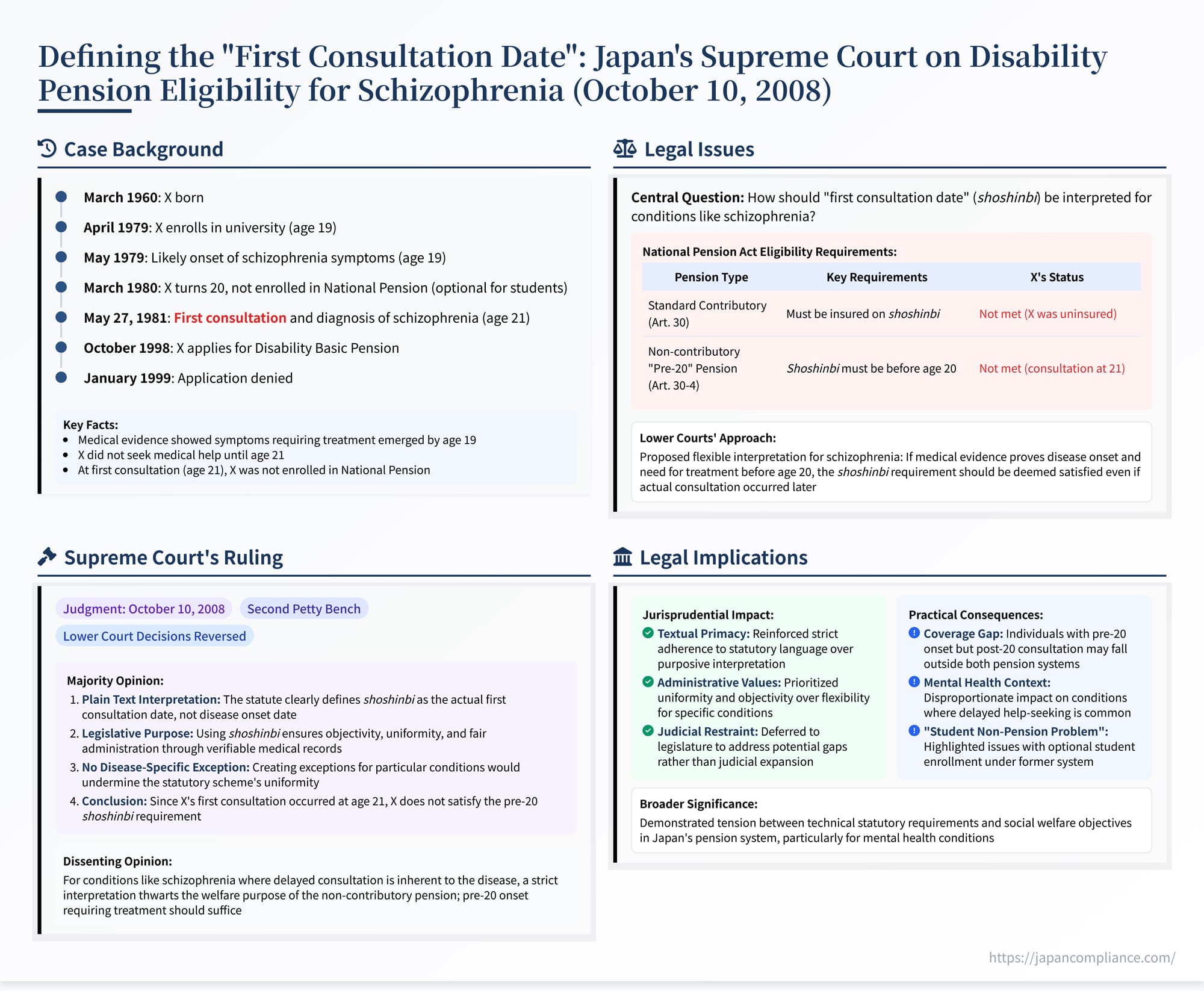

Japan’s Supreme Court (Oct 10 2008) ruled that the literal “first consultation date” (shoshinbi) — not the medical onset date — controls eligibility for the pre‑20 Disability Basic Pension. The Court favored textual certainty over disease‑specific flexibility, leaving legislative reform as the only remedy for students diagnosed after age 20.

Table of Contents

- Factual Background: Delayed Diagnosis and Pension System Rules

- The Legal Framework: Disability Basic Pension and the Shoshinbi Requirement

- Lower Court Rulings: Favoring a Flexible Interpretation for Schizophrenia

- The Supreme Court’s Analysis (October 10 2008)

- The Dissenting Opinion

- Implications and Significance

- Conclusion

On October 10, 2008, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a key judgment concerning the eligibility requirements for the Disability Basic Pension under the National Pension Act (NPA), particularly addressing the interpretation of the "first consultation date" (shoshinbi - 初診日) for conditions like schizophrenia where the onset of the illness and the first time seeking medical help can be significantly separated (Case No. 2007 (Gyo-Hi) No. 68, "Disability Basic Pension Non-Payment Decision Revocation, etc. Case"). The Court grappled with whether the statutory requirement, focusing on the date of first medical consultation, could be interpreted more flexibly for individuals whose disability clearly originated before age 20 but who only sought treatment later, especially under historical pension rules where student enrollment was optional. The Supreme Court ultimately adopted a strict textual interpretation, reaffirming the primacy of the actual first consultation date over the date of disease onset for determining eligibility.

Factual Background: Delayed Diagnosis and Pension System Rules

The case involved an individual facing the challenging intersection of mental illness onset during youth and the intricacies of Japan's pension system rules at the time:

- Medical History: The appellee, X (born March 1960), enrolled in University A in April 1979. In May 1981, at age 21 and still a student, X visited Hospital B's psychiatric department and was diagnosed with neuroleptic malignant syndrome, and subsequently on the same day, with schizophrenia (then known as seishin bunretsubyō), leading to admission at Hospital C. Medical evidence later suggested that X had likely experienced initial symptoms like delusional thoughts as early as May 1979 (age 19) and had developed schizophrenia requiring psychiatric care by age 19 at the latest. However, X had not sought or received any medical consultation for these schizophrenia-related symptoms prior to May 27, 1981.

- Pension Status: When X turned 20 in March 1980, X was a university student. Under the National Pension Act in effect at that time (pre-dating the 1991 mandatory enrollment for students), university students were not automatically enrolled in the National Pension system; enrollment was optional. X had not voluntarily enrolled and was therefore not an insured person under the National Pension system when first diagnosed at age 21 in May 1981.

- Disability Pension Application: Years later, in October 1998, X applied to the Governor of Tokyo Metropolis (the relevant authority at the time) for a Disability Basic Pension (障害基礎年金 - Shōgai Kiso Nenkin), asserting a qualifying level of disability due to schizophrenia.

- Denial of Benefits: In January 1999, the Governor issued a disposition denying X's application ("the Disposition"). The reason was that X did not meet the eligibility requirements for either the standard contributory Disability Basic Pension (because X was not insured on the date of the first consultation) or the non-contributory Disability Basic Pension for pre-20 onset (because the date of the first consultation was after age 20).

- Lawsuit: X sued to revoke the Disposition, naming the successor authority, the appellant Y (Director-General of the Social Insurance Agency), as the defendant.

The Legal Framework: Disability Basic Pension and the Shoshinbi Requirement

Japan's National Pension Act provides for Disability Basic Pensions under two main frameworks:

- Contributory Disability Basic Pension (NPA Art. 30): This is the standard pension for individuals who become disabled. Eligibility requires, among other things, that the individual was an insured person under the National Pension system on their "first consultation date" (shoshinbi) for the disabling condition, and that they meet certain contribution requirements.

- Non-Contributory Disability Basic Pension (NPA Art. 30-4): Often referred to as the "20-sai-mae shōgai kiso nenkin" (Disability Basic Pension for pre-20 disability), this is a non-contributory, welfare-based pension. It is intended as a safety net for individuals who suffered the onset of a disabling condition before reaching age 20 (the standard age for mandatory pension enrollment) and thus may not have had the opportunity to contribute to the system. A key requirement under Art. 30-4 is that the individual "suffered an illness or injury, and whose first consultation date (shoshinbi) for that condition was before they reached 20 years of age."

The Crucial Role of Shoshinbi: The "first consultation date" (shoshinbi) is defined in NPA Art. 30(1) as "the day on which the person first received medical consultation from a doctor or dentist... for the illness or injury that caused the disability, or for a disease resulting therefrom." This date is critical because it serves as the reference point for determining which pension rules apply (contributory vs. non-contributory) and whether the individual was insured or under the qualifying age at the relevant time.

In X's case, the shoshinbi was clearly May 27, 1981, when X was 21. Since X was not insured then, the contributory pension was unavailable. Eligibility hinged entirely on meeting the requirements for the non-contributory pension under Art. 30-4, specifically the requirement that the shoshinbi be before age 20. The factual dispute centered on whether this requirement could be met despite the actual first consultation occurring after age 20, given the medical evidence of disease onset before age 20 and the nature of schizophrenia.

Lower Court Rulings: Favoring a Flexible Interpretation for Schizophrenia

The first instance court and the Tokyo High Court both sided with X, finding the denial of benefits unlawful. Their reasoning centered on a purposive and flexible interpretation of the shoshinbi requirement in the context of schizophrenia:

- Rationale for Shoshinbi: They interpreted the legislative choice of shoshinbi over the actual onset date (hasshōbi - 発症日) as being based primarily on administrative convenience and the technical difficulty for the pension agency in verifying the exact onset date for most conditions. They viewed it as relying on a presumption or legal fiction that, for the majority of illnesses, the onset date and the first consultation date are close in time.

- Breakdown of Presumption for Schizophrenia: They highlighted the specific characteristics of schizophrenia, such as the typical lack of insight into the illness in its early stages and the difficulty in distinguishing early symptoms from normal adolescent/young adult issues, which often leads to a significant delay between the actual onset requiring medical attention and the first time a person seeks or receives medical consultation. For such conditions, the underlying factual premise (proximity of onset and first consultation) breaks down.

- Avoiding Unintended Consequences: They argued that rigidly applying the shoshinbi requirement literally in such cases would defeat the underlying welfare purpose of the non-contributory pension (Art. 30-4), which is to provide support for those disabled before being able to participate in the contributory system. It would unfairly exclude individuals clearly intended to be covered simply because the nature of their illness prevented early consultation.

- Proposed Interpretation: Therefore, the lower courts concluded that for conditions like schizophrenia with this characteristic delay, if post-facto medical diagnosis reliably confirms that the disease onset and the need for medical treatment occurred before age 20, the shoshinbi requirement of Art. 30-4 should be considered satisfied, even if the actual first consultation occurred later. Since X's pre-20 onset requiring treatment was medically established, they ruled X met the requirement.

The Supreme Court's Analysis (October 10, 2008)

The Supreme Court, in its judgment dated October 10, 2008, disagreed with the lower courts' flexible interpretation and adopted a strict textual reading of the statute, ultimately reversing the lower court decisions and upholding the original denial of benefits.

1. Plain Meaning of the Statute:

The Court emphasized the clear language of the National Pension Act. Article 30-4 explicitly requires the shoshinbi to be before age 20. Article 30(1) defines shoshinbi unequivocally as the "date on which the person first received medical consultation." The law uses the term shoshinbi, not hasshōbi (onset date). The Court stated that the meaning derived from the plain text was clear.

2. Legislative Purpose of the Shoshinbi Standard:

The Court explained the rationale behind the legislature's choice to use shoshinbi as the standard:

- Difficulty of Determining Onset Date: The government, as the administrator of the pension system, generally lacks sufficient records or means to accurately determine the precise onset date for every individual illness or injury.

- Ensuring Objectivity: Using the date of the first medical consultation, an event typically documented in medical records, provides a more objective basis for administrative decisions.

- Uniformity and Fairness: Employing a single, verifiable standard (shoshinbi) across different types of conditions ensures that eligibility determinations are made uniformly and fairly, preventing subjective or inconsistent judgments based on attempts to pinpoint potentially ambiguous onset dates. The Court stated the legislative intent was to "define the scope of application... by the date on which medical consultation was received... so that the determination judgment becomes uniform and fair."

3. Rejection of a Disease-Specific Exception:

The Court directly addressed the lower courts' argument regarding the special characteristics of schizophrenia. While acknowledging the reality that onset and first consultation can be far apart for this illness, the majority opinion held that creating a judicial exception based on these characteristics and relying on post-facto medical diagnoses of onset timing would:

- Contradict the clear statutory text: The law explicitly refers to the shoshinbi.

- Undermine the legislative purpose: It would negate the goals of uniformity, fairness, and objectivity that the legislature sought to achieve by adopting the shoshinbi standard in the first place. Different standards would apply based on the type of illness, potentially leading to inconsistencies.

Therefore, the Court concluded that such an expansive interpretation, however well-intentioned from a welfare perspective, could not be adopted as a matter of statutory construction.

4. Application to the Facts:

Since it was undisputed that X first received medical consultation for schizophrenia on May 27, 1981, when X was 21 years old, X did not meet the statutory requirement of having a shoshinbi before age 20. The Court also confirmed that X did not meet the requirements for the contributory pension (not being insured at the shoshinbi) nor for benefits under transitional provisions related to the old Disability Welfare Pension system (which also used a pre-20 shoshinbi requirement).

Conclusion on Legality: As X failed to meet any applicable eligibility requirements, the original decision by the administrative agency to deny the Disability Basic Pension was lawful.

The Dissenting Opinion

One Justice issued a dissenting opinion, largely aligning with the reasoning of the lower courts.

- The dissent emphasized the distinct social welfare purpose of the non-contributory (pre-20 onset) Disability Basic Pension, arguing it aims to support individuals who lost earning capacity before being able to participate in the contributory system.

- It argued that the rationale for the shoshinbi requirement (administrative convenience based on assumed proximity of onset and consultation) does not hold true for diseases like schizophrenia where delayed consultation is inherent.

- Applying the rule strictly in such cases would thwart the fundamental purpose of the pension.

- Therefore, where pre-20 onset requiring medical treatment could be reliably established medically (even retrospectively), an expansive interpretation deeming the shoshinbi requirement met was justified and necessary to fulfill the legislative intent.

- The dissent drew parallels with existing administrative practices for intellectual disabilities and congenital physical disabilities, where eligibility for the pre-20 disability pension is often granted without strictly requiring proof of medical consultation before age 20, effectively treating the shoshinbi as being pre-20 by the nature of the condition.

Implications and Significance

This Supreme Court decision solidified a strict interpretation of the shoshinbi requirement in Japan's disability pension system, with several important consequences:

- Primacy of Textual Interpretation: It demonstrated the Court's strong adherence to the literal text of the statute, even where it might lead to perceived harsh outcomes in specific cases or conflict with the perceived welfare goals for certain conditions.

- Uniformity Over Flexibility: The ruling prioritizes administrative uniformity and objectivity across all types of illnesses over creating disease-specific exceptions, even for conditions with well-recognized characteristics that make meeting the standard difficult.

- Impact on Delayed Diagnosis Cases: It confirms that individuals whose disabling conditions (particularly mental illnesses like schizophrenia) manifest before age 20 but who do not seek medical consultation until after age 20 are generally ineligible for the non-contributory Disability Basic Pension under Article 30-4. Their eligibility depends solely on whether they meet the requirements for the contributory pension based on their insurance status at the later shoshinbi.

- Potential Coverage Gaps: The decision highlights a potential gap in Japan's social safety net, particularly concerning individuals who were students under the former optional enrollment system and developed conditions like schizophrenia before age 20 but were diagnosed later. They could fall outside both the non-contributory (due to late shoshinbi) and contributory (due to lack of insurance at shoshinbi) systems. This issue was part of the broader "student non-pension problem" (gakusei munenkin mondai) that spurred later legislative reforms making student enrollment mandatory.

- Legislative vs. Judicial Role: By refusing to adopt an expansive interpretation, the Court implicitly placed the onus on the legislature (the Diet) to address any perceived inequities or gaps resulting from the strict application of the shoshinbi rule, rather than attempting to resolve them through judicial interpretation.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's October 10, 2008, judgment provided a definitive interpretation of the "first consultation date" (shoshinbi) requirement for Japan's non-contributory Disability Basic Pension (for pre-20 onset). The Court held that the statutory language must be applied strictly, meaning the actual date of the first medical consultation is the determining factor, not the date of disease onset. This interpretation was upheld even for conditions like schizophrenia where a delay between onset and consultation is common, based on the legislative goals of administrative objectivity, uniformity, and fairness. While ensuring consistent application across diseases, the ruling highlighted potential difficulties for individuals with certain conditions in accessing disability benefits under this specific provision and underscored the critical importance of the documented shoshinbi in the Japanese pension system.

- Student Disability Pension Gap: Why Japan’s Supreme Court Backed Voluntary Enrollment (2007)

- Japan Supreme Court 2023 Pension‑Cut Ruling: Balancing Sustainability and Recipient Rights

- The Horiki Litigation: Legislative Discretion and Social Security Benefits in Japan

- Eligibility, Application Timing, and Pension Amounts for Disability Basic Pension

- Overview of Disability Pension Requirements and First Consultation Date