Defining the "Employer" in Collective Bargaining: The Asahi Broadcasting Supreme Court Judgment

Judgment Date: February 28, 1995

Case Name: Claim for Revocation of an Unfair Labor Practice Remedy Order (Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench)

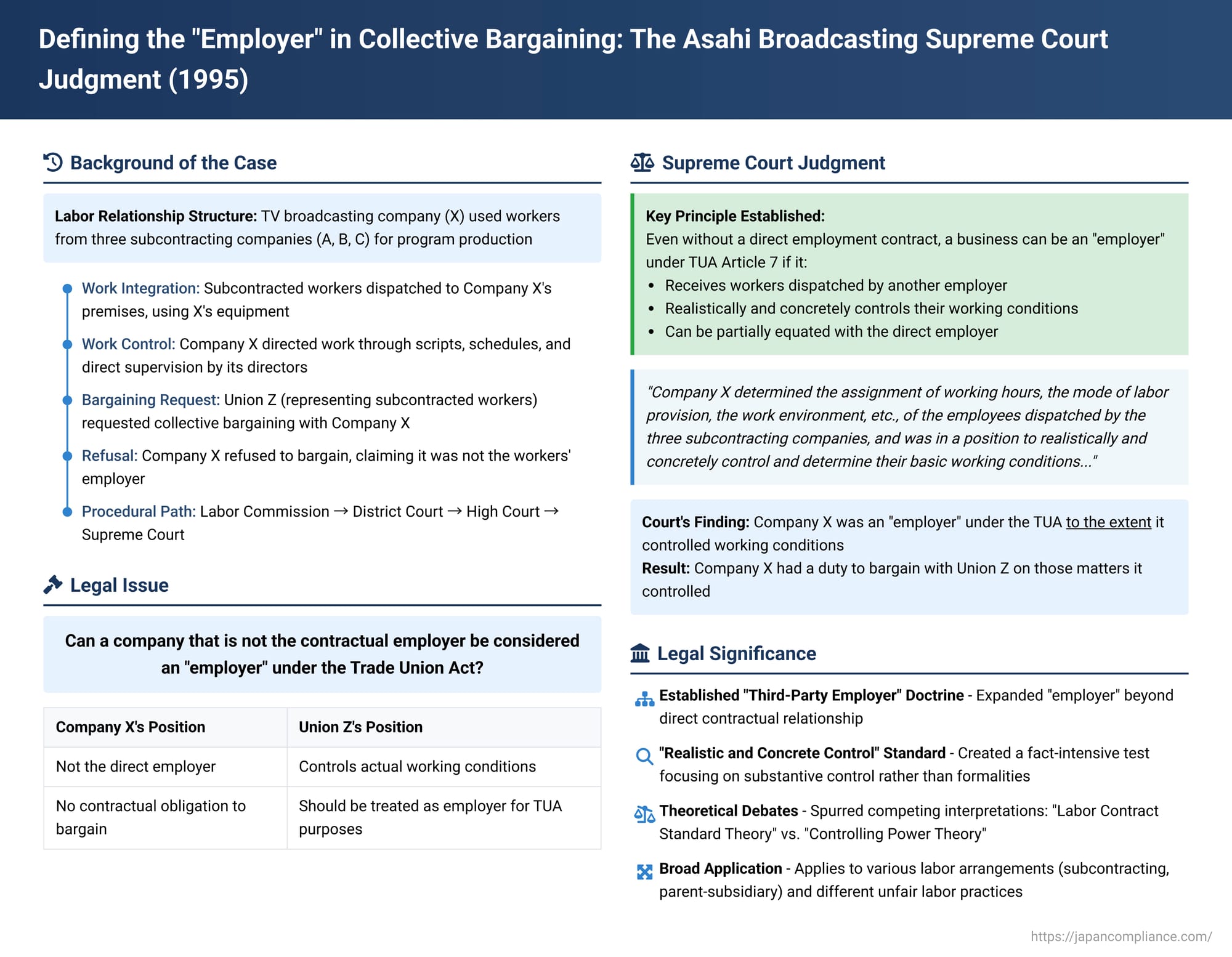

In the evolving landscape of labor relations, identifying the responsible "employer" for the purposes of collective bargaining under Japan's Trade Union Act (TUA) can be complex, especially when workers are engaged through subcontracting or dispatch arrangements. The Japanese Supreme Court's judgment in the Asahi Broadcasting case, delivered on February 28, 1995, stands as a seminal decision. It established that a business entity, even if not the direct contractual employer, could be deemed an "employer" under the TUA if it exercises significant control over the working conditions of another company's employees working within its operations.

Factual Background of the Dispute

Company X, a television broadcasting business, extensively utilized workers from three subcontracting companies (referred to collectively as "the three subcontracting companies" or Companies A, B, and C) for its television program production. Company X had ongoing service (請負 - ukeoi, or contracting) agreements with Company A and Company C. Company B, in turn, had a subcontracting agreement with Company A, performing some of the work Company A had contracted from Company X.

Under these arrangements:

- Integration of Subcontracted Workers: Employees of the three subcontracting companies were dispatched to Company X's premises to engage in program production. The individuals dispatched for Company X's program production work remained largely the same over time, indicating a stable, ongoing relationship.

- Company X's Control Over Work Performance:

- Detailed Instructions: Company X determined the specifics of the tasks to be performed by the dispatched employees. This was done through monthly programming schedule charts (編成日程表 - hensei nittei hyō), scripts (台本 - daihon), and production schedules (制作進行表 - seisaku shinkō hyō), which detailed work dates, start and end times, work locations, and the content of the work.

- Direct Supervision: The actual progress of the work performed by the subcontracted employees was entirely under the direction and supervision of Company X's own employees, specifically its program directors. These directors had the authority to change work schedules, extend working hours beyond planned times, and decide the timing and duration of breaks for the subcontracted employees, based on the evolving needs of production.

- Equipment and Work Environment: The subcontracted employees used equipment supplied or lent by Company X and were integrated into Company X's operational work order, working alongside Company X's direct employees.

- Role of the Subcontracting Companies (Direct Employers):

- The three subcontracting companies were legally distinct business entities. They were the direct contractual employers of the dispatched workers.

- Their primary role in the day-to-day assignment process was to decide which specific individuals from their largely fixed pool of employees would be assigned to which program production tasks, based on the schedules provided by Company X.

- These subcontracting companies maintained their own work rules and were responsible for paying their employees' wages, including calculating overtime based on attendance records (which were based on the employees' self-reporting of their work at Company X).

- Notably, the three subcontracting companies independently engaged in collective bargaining with Union Z (the union to which some of their dispatched employees belonged) regarding matters such as wage increases and seasonal bonuses, and had concluded collective agreements on these issues.

The Labor Dispute and Procedural Pathway

Union Z, representing some of the employees of the three subcontracting companies who were engaged in production work at Company X, approached Company X directly with a request for collective bargaining. The union's demands included wage increases, payment of bonuses, the regularization (conversion to direct employee status with Company X) of the subcontracted employees, and improvements in working conditions, such as the provision of a rest area.

Company X refused to negotiate with Union Z, asserting that it was not the legal employer of these workers and therefore had no obligation to bargain with their union.

Following this refusal, Union Z filed an unfair labor practice complaint with the Osaka Local Labor Commission.

- Local Labor Commission: The commission found that Company X's refusal to bargain constituted an unfair labor practice for certain matters and issued a partial remedy order.

- Central Labor Commission (CLC): On review, the CLC largely upheld the local commission's findings. It issued an order stating that Company X "must not refuse to engage in collective bargaining with Union Z concerning work assignments and other working conditions related to program production work for [Union Z's] members, on the grounds that it is not their employer." The CLC also maintained the initial order concerning domination/interference (an aspect of unfair labor practices).

- Company X's Lawsuit: Company X filed a suit in court seeking the revocation of the CLC's order.

- Court of First Instance (Tokyo District Court): This court dismissed Company X's claim, effectively upholding the CLC's decision.

- Court of Second Instance (Tokyo High Court): The High Court reversed the lower court's decision. It ruled in favor of Company X, revoking the CLC order. The High Court found that Company X did not qualify as an "employer" of the subcontracted workers under Article 7 of the TUA. The CLC, supported by Union Z as an auxiliary intervenor, appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment

The Supreme Court, on February 28, 1995, overturned the High Court's decision and largely reinstated the CLC's order concerning the duty to bargain.

- Defining "Employer" Under TUA Article 7:

The Court began by addressing the meaning of "employer" in TUA Article 7, which prohibits certain employer actions as unfair labor practices. It acknowledged that "employer" generally refers to the contractual employer. However, considering the TUA's objective of rectifying infringements on the right to organize and restoring normal labor relations, the Court established a broader principle:

"Even if a business operator is not the contractual employer, if it receives workers dispatched by the employer to engage in its own business, and is in a position to realistically and concretely control and determine the basic working conditions, etc., of those workers to an extent that it can be partially equated with the employer, then to that extent, said business operator falls under 'employer' in said article." - Application of the Principle to the Facts:

The Supreme Court found that although Company X was not the contractual employer of the dispatched workers, the facts of the case demonstrated that Company X met this newly articulated standard:Based on these comprehensive factual findings, the Supreme Court concluded:

"In substance, Company X determined the assignment of working hours, the mode of labor provision, the work environment, etc., of the employees dispatched by the three subcontracting companies, and was in a position to realistically and concretely control and determine their basic working conditions, etc., to an extent that it could be partially equated with their employers, the three subcontracting companies. Therefore, to that extent, it is appropriate to interpret Company X as falling under 'employer' as stipulated in Article 7 of the Trade Union Act."- Company X determined all aspects of the work for the dispatched employees, including detailed work schedules, locations, content, and procedures through its programming charts, scripts, and production schedules.

- The subcontracting companies' role was limited to merely assigning their mostly fixed personnel to the tasks already defined by Company X.

- The dispatched employees were integrated into Company X's work processes, used its equipment, and worked alongside its direct employees according to Company X's operational order.

- Crucially, the progression of their work, including modifications to work hours, extensions, and breaks, was entirely under the command and supervision of Company X's employee directors.

- Consequences for Collective Bargaining:

As Company X was deemed an "employer" concerning the working conditions it could control (such as work assignments, the manner of work performance, and the work environment), it could not, without a legitimate reason, refuse to bargain collectively with Union Z on these matters. Company X's blanket refusal, based on the claim that it was not an employer, was therefore found to constitute an unfair labor practice under TUA Article 7(2) for those negotiable items falling within its sphere of control. - Disposition:

The Supreme Court quashed the High Court's judgment. Regarding the part of the CLC order compelling Company X to bargain (Main Text Paragraph 1 of the CLC order), the Supreme Court rejected Company X's appeal from the Court of First Instance, thereby upholding the duty to bargain on controllable terms. Regarding the part of the CLC order concerning domination/interference (Main Text Paragraph 2 of the CLC order, which upheld Main Text Paragraph 2 of the initial Local Labor Commission order), the Supreme Court remanded this aspect to the Tokyo High Court for further proceedings. This remand was to allow the High Court to re-examine whether domination or interference had occurred, now on the premise that Company X was an employer under the TUA.

Analysis and Significance of the Judgment

The Asahi Broadcasting judgment is a landmark in Japanese labor law, significantly shaping the understanding of employer responsibility in situations involving third-party labor.

- Establishment of "Third-Party Employer" Doctrine:

The most crucial contribution of this case is the Supreme Court's explicit recognition that a business entity (a "third party" or "user" company) that is not the direct contractual employer can nevertheless be held responsible as an "employer" under the TUA for collective bargaining purposes. This addressed the reality of modern labor markets where the entity benefiting from and controlling labor is not always the formal employer. - The "Realistic and Concrete Control" Standard:

The judgment introduced the pivotal standard of "realistic and concrete control and determination" over "basic working conditions" to an extent "partially comparable" to the direct employer. This is a fact-intensive test that looks beyond formal contractual relationships to the substantive realities of power and control in the workplace. The phrase "to that extent" (その限りにおいて - sono kagiri ni oite) is critical, implying that the third party's employer status is not absolute but is limited to those matters over which it exercises such control. - Theoretical Interpretations and Debates:

The judgment has spurred considerable academic discussion regarding its theoretical underpinnings:- "Labor Contract Standard Theory" (労働契約基準説): Proponents of this view argue that TUA employer status is fundamentally anchored in the employment contract or relationships closely analogous to it. They interpret the Asahi Broadcasting decision as recognizing a "partial employer" status for the third party – meaning it assumes employer responsibilities only for those specific working conditions it controls, effectively sharing employer functions with the direct employer.

- "Controlling Power Theory" (支配力説): This perspective posits that a TUA employer is any entity wielding significant de facto control or influence over labor relations, sufficient to trigger the TUA's unfair labor practice provisions, irrespective of a direct contractual link. Adherents see the judgment as endorsing "overlapping employer status," where both the direct employer and the controlling third party can simultaneously be considered employers for the same bargaining subjects, based on the third party's concrete controlling power.

- Eclectic/Hybrid Views: Some scholars suggest the Supreme Court adopted a hybrid approach, grounding its decision in the labor contract framework but incorporating the "realistic and concrete control" language, which resonates with the controlling power theory.

- Scope and Application of the Judgment (射程 - shatei):

Significant debate surrounds the intended scope of the Asahi Broadcasting criteria:- Indirect Control (e.g., Parent-Subsidiary): Can the criteria, developed in a case of dispatched/subcontracted workers (an "external worker utilization type" scenario), be applied to situations where a parent company influences the labor conditions of its subsidiary's employees (an "indirect control type" scenario)? The Labor Contract Standard Theory (and hybrid views) generally affirm this, viewing the criteria as a general standard. Many CLC orders and court rulings have followed this line. Conversely, the Controlling Power Theory tends to argue against direct application, suggesting that the "realistic and concrete control" language might paradoxically make it difficult to hold parent companies accountable for broader employment issues within subsidiaries they generally dominate.

- Demands for Direct Employment by the User Company: A particularly contentious area is whether these criteria apply when a union demands that the user company (e.g., Company X) directly hire the workers dispatched by a subcontractor.

- Some adhering to the Labor Contract Standard Theory argue that for such demands, the user company must be shown to have realistic and concrete control not just over daily working conditions, but over the very employment relationship itself (hiring, deployment, termination).

- Others within this school of thought find this too restrictive, suggesting that substantial involvement or influence in these employment decisions by the user company should suffice.

- A different line of judicial interpretation suggests focusing on whether the user company has realistic and concrete control over the specific matter demanded (e.g., if dismissal is the issue, control over dismissal), rather than global control over hiring.

- The Controlling Power Theory often posits that the Asahi Broadcasting criteria are ill-suited for direct employment demands, as the original direct employer (the subcontractor) typically lacks the authority to decide on hiring by the user company. Instead, employer status for such demands should be determined by whether the user company has the power and standing to resolve the dispute.

- These differing interpretations often reflect deeper disagreements about the fundamental purpose and function of collective bargaining: whether it is primarily a tool for negotiating the terms and conditions of employment within an existing or quasi-employment framework, or a broader mechanism for dispute resolution with any entity holding decisive power.

- Application to Other Unfair Labor Practices:

The criteria for determining "employer" status laid down in Asahi Broadcasting are generally understood to apply not only to refusals to bargain (TUA Article 7(2)) but also to other unfair labor practices, such as discriminatory treatment against union members (Article 7(1)) and domination or interference in union activities (Article 7(3)). The judgment itself remanded the domination/interference claim for re-evaluation on the premise of Company X's employer status. This implies that if an entity is an employer for certain bargaining matters, its responsibilities under Article 7 extend beyond merely the scope of mandatory bargaining subjects for those specific items.

Conclusion

The Asahi Broadcasting Supreme Court judgment marked a significant development in Japanese labor law. By looking beyond formal employment contracts to the realities of control over working conditions, the Court expanded the concept of "employer" for the purposes of the Trade Union Act. This decision acknowledged that entities benefiting from and substantively directing labor have a responsibility to engage in collective bargaining regarding the conditions they effectively determine. The "realistic and concrete control" standard, while subject to ongoing interpretation and debate concerning its precise scope, remains a cornerstone for analyzing employer obligations in complex, multi-tiered labor arrangements, and is crucial for ensuring meaningful collective bargaining rights in contemporary workplaces.