Defining the Divisible Pie: Japan's Supreme Court on the "Suit for Confirmation of Estate Property"

Date of Judgment: March 13, 1986

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Case No. Showa 57 (o) No. 184 (Claim for Confirmation of Estate Property)

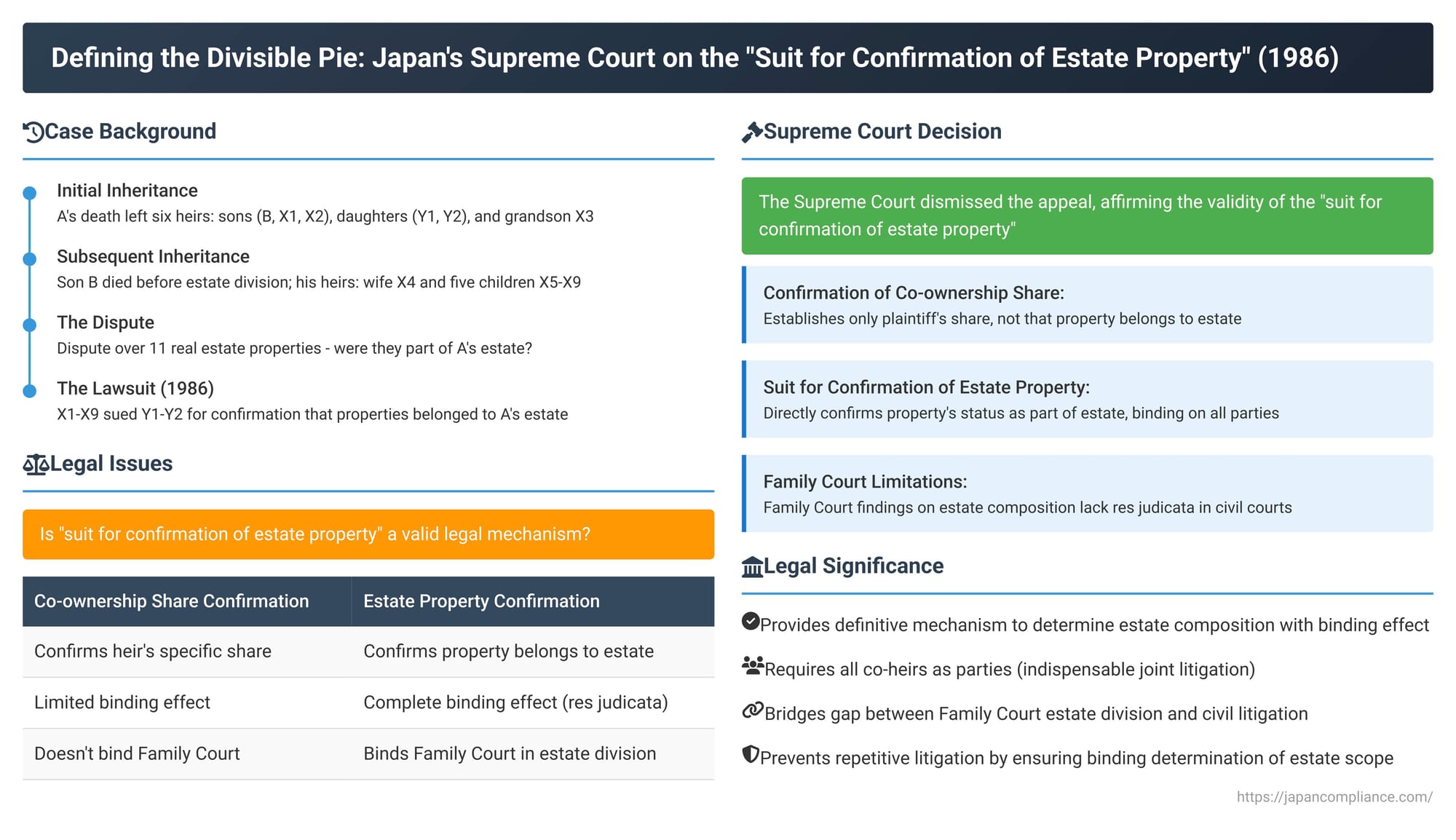

The division of an inherited estate among co-heirs can be a complex process. One of the fundamental, and often contentious, preliminary steps is determining precisely which assets belonged to the deceased and therefore form part of the divisible estate. When co-heirs dispute whether a particular property is part of the estate, a procedural mechanism is needed to resolve this issue definitively. The Supreme Court of Japan, in its decision on March 13, 1986, affirmed the validity and outlined the nature of a "suit for confirmation of estate property" (遺産確認の訴え - isan kakunin no uttae), providing a crucial tool for heirs to establish the scope of the inheritable estate with binding effect.

Facts of the Case

The case involved a multi-generational inheritance and a dispute over several real estate properties.

- The Initial Inheritance (A's Death): A passed away, leaving six initial co-heirs: his eldest son B, second son X1, third son X2, second daughter Y1, third daughter Y2, and X3 (the child of A's predeceased eldest daughter C)[cite: 1].

- Subsequent Inheritance (B's Death): Before A's estate could be formally divided, A's son B also passed away. B's heirs were his wife X4 and their five children, X5 through X9[cite: 1]. This brought the total number of interested parties in A's estate to eleven, combining the remaining direct heirs of A and the heirs of B.

- The Dispute: A disagreement arose concerning eleven items of real estate or co-ownership shares in real estate (collectively, the "Disputed Properties"). The plaintiffs, X1 through X9 (comprising some of A's direct heirs and all of B's heirs), asserted that these Disputed Properties belonged to A's estate[cite: 1]. The defendants, Y1 and Y2 (daughters of A), contested this assertion[cite: 1].

- The Lawsuit: Consequently, X1-X9 filed a lawsuit against Y1 and Y2, seeking a judicial confirmation that the Disputed Properties were indeed part of A's estate[cite: 1]. (During the first instance proceedings, plaintiff X4 passed away, and her legal heirs, X10 and X11, succeeded her position in the lawsuit [cite: 1]).

- Lower Court Rulings: Both the Kyoto District Court (first instance) and the Osaka High Court (appellate court) found the suit for confirmation of estate property to be procedurally proper and ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, X1-X9, confirming that the Disputed Properties belonged to A's estate[cite: 1]. Y2, one of the defendants, appealed this decision to the Supreme Court[cite: 1].

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal, upholding the decisions of the lower courts and affirming the legitimacy of a "suit for confirmation of estate property." The Court's reasoning was detailed:

- Admissibility of a Suit Confirming Co-ownership Share: The Court first acknowledged that it is permissible for a co-heir to file a lawsuit to confirm their own specific co-ownership share in a particular property, based on their statutory inheritance percentage, if there's a dispute about whether that property belongs to the estate[cite: 1]. Typically, such a suit might achieve the plaintiff's objective[cite: 1].

- Limitations of a Share-Confirmation Suit: However, the Court highlighted a critical limitation: a final judgment in a suit merely confirming an heir's co-ownership share only establishes, with res judicata (binding effect), that the plaintiff holds that particular share[cite: 1]. It does not definitively establish with res judicata that the underlying reason for acquiring that share was inheritance from the specific deceased, nor does it bind subsequent Family Court estate division proceedings on the question of whether the property itself belongs to the estate[cite: 1].

The Court referenced its own Showa 41 (1966) Grand Bench decision, which held that while the Family Court, in an estate division adjudication (遺産分割審判 - isan bunkatsu shinpan), can make findings on preliminary issues like the scope of the estate, such findings do not have res judicata effect in separate civil litigation[cite: 1]. Thus, even after an estate division by the Family Court based on its own determination of the estate's scope, a later civil court judgment could contradict this finding, potentially invalidating the Family Court's division decree regarding that property[cite: 1]. This outcome would not align with a plaintiff's intention to achieve a final resolution on the property's inclusion in the estate[cite: 1]. - The "Suit for Confirmation of Estate Property" – A More Effective Solution:

In contrast, the "suit for confirmation of estate property" does not primarily concern itself with the percentage of each co-heir's share[cite: 1]. Instead, it directly seeks a judicial declaration that the disputed property currently belongs to the deceased's estate – or, put another way, that the property is currently in a state of co-ownership by the co-heirs, pending estate division[cite: 1].

A final judgment in favor of the plaintiffs in this type of suit does establish with res judicata that the property is, in fact, part of the estate and thus subject to estate division[cite: 1]. This binding determination prevents the parties from later contesting the property's status as estate property, both in subsequent Family Court estate division proceedings and in any related future civil actions[cite: 1]. This provides a more conclusive and dispute-ending resolution that better meets the plaintiff's objective[cite: 1]. - Nature of Estate Co-ownership and Procedural Differences:

The Court reaffirmed that the legal nature of co-ownership of an undivided estate by co-heirs is fundamentally the same as ordinary co-ownership governed by Article 249 et seq. of the Civil Code[cite: 1]. However, the judicial procedures for resolving these two types of co-ownership differ: estate co-ownership is typically resolved through Family Court estate division adjudications, while ordinary co-ownership is resolved through civil court partition lawsuits (共有物分割訴訟 - kyōyūbutsu bunkatsu soshō)[cite: 1]. The legal effects of property acquisition through these distinct procedures also vary[cite: 1].

The Supreme Court concluded that recognizing the "suit for confirmation of estate property" as a valid legal recourse, due to the necessities arising from these systemic procedural differences, is not inconsistent with the basic legal similarity between estate co-ownership and ordinary co-ownership[cite: 1].

Therefore, the Supreme Court held that the original suit filed by the plaintiffs was procedurally proper, and it upheld the High Court's judgment which had found in their favor on the merits.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1986 Supreme Court decision has several important implications for inheritance law and practice in Japan:

- Ensuring Finality in Estate Scope: The primary significance of this ruling is that it provides a clear procedural path for co-heirs to obtain a definitive, legally binding judgment on whether disputed assets belong to the deceased's estate. The res judicata effect of such a judgment is crucial for streamlining subsequent estate division proceedings in the Family Court, as the scope of divisible assets is no longer open to challenge between the parties to the confirmation suit.

- Addressing the Limits of Family Court Adjudications: The decision directly addresses the issue highlighted by the 1966 Grand Bench ruling: Family Court findings on preliminary matters like estate composition lack res judicata in civil courts. The "suit for confirmation of estate property" fills this gap by allowing for a civil court judgment with such binding effect.

- Characterization as a "Confirmation of Co-ownership": The Supreme Court framed the "suit for confirmation of estate property" as a specific type of "suit for confirmation of co-ownership"[cite: 1]. This characterization has implications for procedural aspects, particularly party standing. It suggests that the suit is about confirming the collective ownership of the asset by the co-heirs as a group, pending division[cite: 2].

- Indispensable Joint Litigation (固有必要的共同訴訟 - koyū hitsuyōteki kyōdō soshō): By viewing this suit as a form of confirming co-ownership, it logically follows that all co-heirs must be joined as parties (either as plaintiffs or defendants) for the judgment to have a unified effect on all involved. This is because a dispute over whether property belongs to an estate inherently affects the rights of all co-heirs. Indeed, a subsequent Supreme Court decision in Heisei 1 (1989) explicitly confirmed that a "suit for confirmation of estate property" is indispensable joint litigation[cite: 3].

- Theoretical Basis for the Suit: Traditional Japanese procedural theory posits that a suit for confirmation (確認の訴え - kakunin no uttae) must concern a legal right or relationship, not merely a factual matter. Framing the "suit for confirmation of estate property" as a confirmation of the co-ownership relationship among the heirs with respect to the disputed property aligns with this theory, lending it procedural legitimacy[cite: 2].

- Applicability to Various Property Types: While the specific case involved real estate, the principle has broader application. The PDF commentary notes the evolution of case law concerning divisible assets like bank deposits. Initially, such assets were often considered automatically divided among heirs according to their shares upon inheritance. However, a series of more recent Supreme Court decisions has held that many types of financial claims (e.g., certain bank deposits, investment trusts) do not automatically divide and instead become part of the estate subject to formal division[cite: 3]. These types of assets can therefore also be the subject of a "suit for confirmation of estate property"[cite: 3].

Ongoing Discussion and Nuances

The PDF commentary also alludes to some evolving interpretations and potential nuances in the case law[cite: 4]. For instance, a later Supreme Court decision in Heisei 9 (1997) suggested that the standing to bring a "suit for confirmation of estate property" might be grounded more in an individual's status as a "co-heir" rather than strictly as a "co-owner" of the specific disputed asset. This could be relevant if, for example, an heir's specific co-ownership claim to an asset had been previously denied in a suit against another heir, but their status as an heir or the general character of the property as belonging to the deceased's original holdings was not negated[cite: 4]. This could imply that the suit is fundamentally about defining the "estate" as a special collective property of the heirs, rather than just confirming ordinary co-ownership[cite: 4].

Conclusion

The 1986 Supreme Court decision on the "suit for confirmation of estate property" provides an indispensable procedural tool in Japanese inheritance disputes. By allowing co-heirs to obtain a civil court judgment with res judicata on the question of whether specific assets belong to the deceased's estate, it promotes legal certainty and efficiency. This ruling helps prevent repetitive litigation and ensures that subsequent estate division proceedings in the Family Court can proceed on a clearly defined and legally binding foundation regarding the scope of the assets to be divided. It underscores the judiciary's practical approach to resolving complex, multi-party inheritance conflicts.