Japan Supreme Court on Public Assistance for Undocumented Foreign Residents (2001)

TL;DR

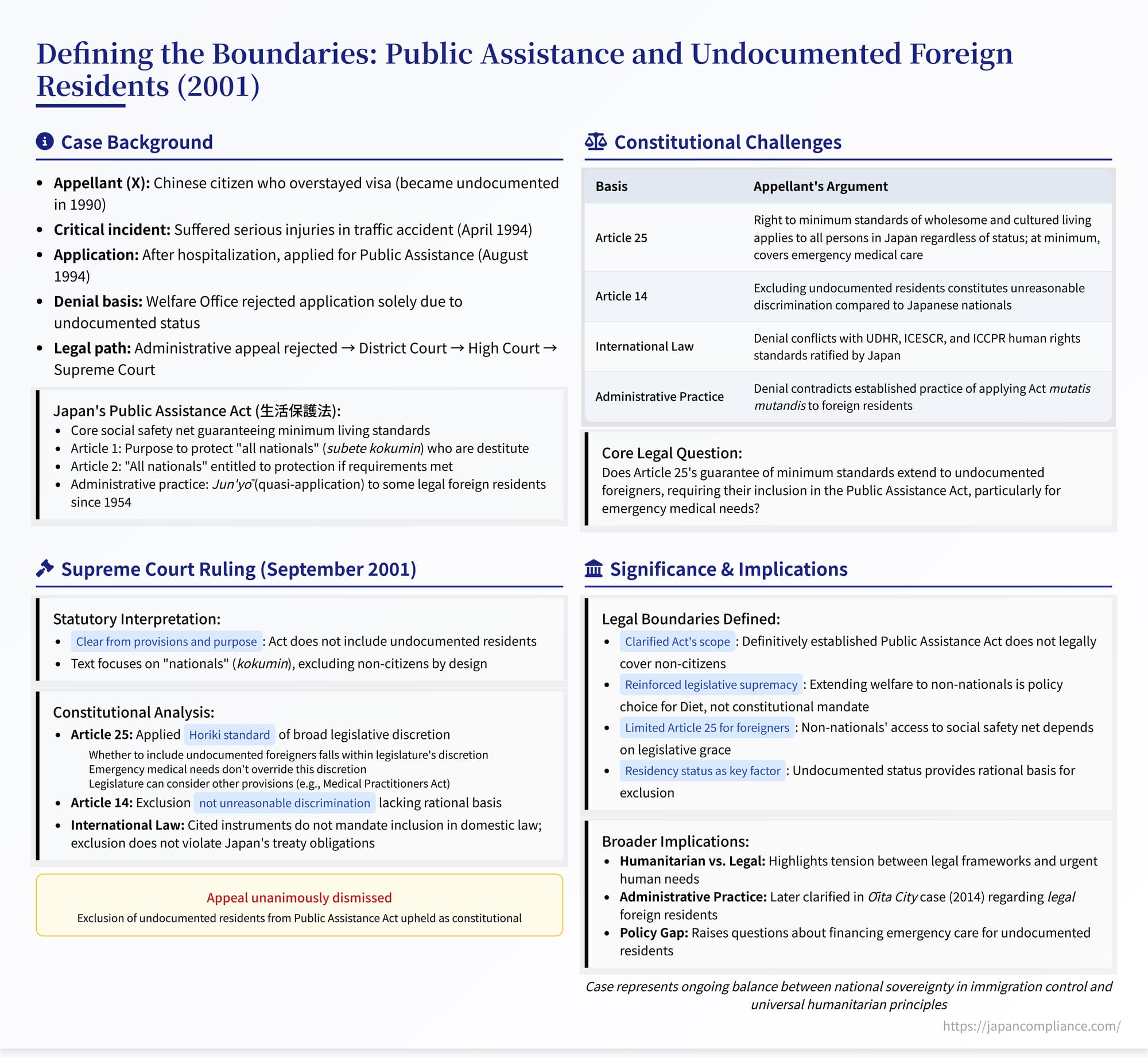

Japan’s Supreme Court (Sept 25 2001) held that undocumented foreign residents are not legally entitled to benefits under the Public Assistance Act. Relying on Horiki precedent, the Court ruled that (i) Article 25 imposes only a programmatic duty subject to broad legislative discretion, (ii) excluding undocumented residents is not unreasonable discrimination under Article 14, and (iii) international human‑rights covenants do not override explicit statutory language limiting protection to “nationals.”

Table of Contents

- Background: An Accident and a Denial of Aid

- The Constitutional and Legal Challenge

- The Supreme Court’s Decision: Upholding Exclusion

- Significance and Analysis

- Conclusion

The question of access to social safety nets for non-citizens, particularly those without legal residency status, presents complex legal and ethical challenges globally. How does a nation balance its constitutional commitments to human dignity and minimum living standards with the legal framework governing immigration and citizenship? Japan's Supreme Court tackled this issue directly in a significant 2001 decision involving an undocumented foreign resident seeking public assistance after a serious accident. This case, formally the Case Concerning Request for Revocation of Disposition Rejecting Public Assistance Application (Supreme Court, Third Petty Bench, Heisei 9 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 176, Sept. 25, 2001), clarified the scope of Japan's core public assistance law and affirmed the broad discretion of the legislature in determining social security eligibility for non-nationals, even in situations involving urgent medical needs.

Background: An Accident and a Denial of Aid

The appellant, X, was a citizen of the People's Republic of China. X initially entered Japan legally in August 1988 under a specific visa category granted by the Minister of Justice (under the pre-1989 Immigration Control Act). After returning to China temporarily, X re-entered Japan in February 1990. However, X's authorized period of stay expired in August 1990. X did not apply for an extension or change of status and continued residing in Japan, thereby becoming an undocumented resident (referred to in the judgment as 不法残留者, fuhō zanryūsha, often translated as "illegal overstayer").

In April 1994, X was involved in a traffic accident, suffering serious injuries including a skull fracture, which required hospitalization. Following discharge from the hospital in June 1994, X applied for public assistance under Japan's Public Assistance Act (生活保護法, Seikatsu Hogo Hō) in August 1994. This Act is the cornerstone of Japan's social safety net, intended to guarantee a minimum standard of living for those in need.

The Director of the local Welfare Office (in Nakano Ward, Tokyo) rejected X's application. The sole reason provided for the rejection was X's status as an undocumented resident. An administrative appeal filed by X to the Governor of Tokyo was subsequently dismissed on the grounds that X lacked standing to appeal.

The Constitutional and Legal Challenge

X challenged the Welfare Office Director's rejection in court, arguing that the denial was illegal and unconstitutional. The core arguments presented were:

- Violation of Article 25 (Right to Minimum Standards of Living): X contended that Article 25 of the Japanese Constitution, which guarantees the right to maintain "minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living," applies to all persons residing in Japan, including foreigners regardless of their residency status, at least concerning the right to receive emergency medical care. X argued that the Public Assistance Act should be interpreted in light of this constitutional guarantee to cover, at a minimum, the provision of aid necessary for such emergency situations.

- Violation of Article 14 (Equality under the Law): X argued that excluding undocumented residents from public assistance constituted unreasonable discrimination compared to Japanese nationals, violating the equality guarantee in Article 14(1).

- Violation of International Law: X asserted that the denial conflicted with international human rights standards, citing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and international covenants ratified by Japan, specifically the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).

- Contradiction of Administrative Practice: X also pointed to the long-standing administrative practice (based on a 1954 notification from the Ministry of Health and Welfare) whereby the Public Assistance Act had been applied mutatis mutandis (準用, jun'yō - essentially, applied by analogy) to certain categories of foreign residents in need, arguing the denial contradicted this established practice. (Although not detailed in the judgment itself, historical context indicates this practice existed but became more restrictive over time, particularly after 1990 immigration law changes, often limiting quasi-application to those with specific legal residency statuses like permanent or long-term residents).

The Tokyo District Court and the Tokyo High Court both dismissed X's claims. They held that the Public Assistance Act, by its text, applies only to Japanese nationals. They found that excluding foreigners, particularly undocumented residents, was within the scope of legislative discretion under Article 25 and did not constitute unreasonable discrimination under Article 14. They also ruled that international instruments did not override domestic law to mandate coverage in this instance. X appealed these decisions to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Upholding Exclusion

The Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court unanimously dismissed X's appeal, affirming the lower courts' rulings and solidifying the legal position that undocumented foreign residents are not eligible for benefits under Japan's Public Assistance Act.

1. Statutory Interpretation of the Public Assistance Act:

The Court's starting point was the text of the Public Assistance Act itself. It stated unequivocally that it is "clear from its provisions and purpose" that the Act does not include undocumented residents within its scope of protection. While the judgment doesn't explicitly cite the articles, this interpretation rests firmly on Article 1, which states the Act's purpose is to provide necessary protection to "all nationals" (subete kokumin) who are destitute, and Article 2, which states that "all nationals" (subete kokumin) are entitled to protection under the Act provided they meet the requirements. The Court found the exclusion of non-nationals, especially those without legal status, to be evident from the law's own terms.

2. Reasoning on Article 25 (Right to Minimum Standards of Living):

The Court then addressed the core constitutional claim under Article 25. It firmly rejected the argument that Article 25 directly guarantees rights, including emergency medical care, to undocumented foreigners that would compel their inclusion under the Public Assistance Act.

- Reiteration of Programmatic Rights and Legislative Discretion: The Court relied heavily on the established constitutional doctrine, citing the Horiki decision (which itself built on Asahi). It reiterated that Article 25(1) declares a state duty, not a directly enforceable individual right. Concrete rights are established through legislation enacted pursuant to the state's duty under Article 25(2). The crucial point, repeatedly emphasized in precedent, is that the choice and determination of what specific legislative measures to enact in response to Article 25 rests within the broad discretion of the legislature (the Diet).

- Application to Non-Nationals: The Court explicitly applied this principle to the question of covering non-nationals. It stated that whether to include foreigners, specifically undocumented residents, within the scope of protection under the Public Assistance Act clearly falls within the scope of legislative discretion.

- Emergency Medical Care Does Not Alter Discretion: The Court directly addressed X's argument regarding emergency medical care. It held that the principle of legislative discretion applies even in cases where an undocumented resident requires urgent medical treatment. The legislature can decide whether or not to extend Public Assistance Act coverage to such situations. In making this policy choice, the legislature can consider various factors, including the existence of other relevant legal provisions, such as Article 19(1) of the Medical Practitioners Act (which generally obligates doctors not to refuse treatment requests without justifiable grounds, though its application and enforcement, especially regarding payment, can be complex). The existence of a medical emergency does not automatically trigger a constitutional right to public assistance under Article 25 for someone excluded by the legislature's policy choice.

- Conclusion on Article 25: Therefore, the Court concluded, the fact that the Public Assistance Act does not cover undocumented residents does not violate Article 25. The legislature acted within its constitutional discretion in limiting the Act's scope primarily to nationals.

3. Reasoning on Article 14 (Equality):

The Court's analysis of the Article 14(1) equality claim was brief but decisive.

- It stated that excluding undocumented residents from the protection of the Public Assistance Act does not constitute unreasonable discriminatory treatment without rational basis.

- Therefore, it does not violate Article 14(1).

- The Court supported this conclusion by citing several key precedents: the Horiki decision itself (which upheld differential treatment in social security based on legislative discretion), the McLean decision (Supreme Court, 1978, affirming that while fundamental human rights extend to foreigners, distinctions based on nationality are permissible where rational, especially regarding political rights and potentially residency status), and other cases confirming that the equality guarantee prohibits unreasonable discrimination, allowing for distinctions based on rational grounds. Implicitly, the Court found the distinction between nationals/legal residents and undocumented residents to be a rational basis for differential treatment regarding eligibility for this specific social security program.

4. Reasoning on International Law:

The Court also addressed X's arguments based on international human rights instruments.

- It affirmed the lower court's finding that the cited instruments – the UDHR, the ICESCR, and the ICCPR – do not serve as a legal basis for interpreting Japan's domestic Public Assistance Act as including undocumented residents within its scope. While these instruments articulate broad rights, the Court viewed them as not directly mandating coverage under this specific national statute for this specific group.

- Furthermore, based on its finding that the exclusion was a constitutional exercise of legislative discretion, the Court concluded that the provisions of the Public Assistance Act (in excluding undocumented residents) do not violate the provisions of the cited international covenants (ICESCR and ICCPR).

Significance and Analysis

This 2001 Supreme Court decision remains a critical reference point in discussions about the rights of foreign residents, particularly undocumented individuals, within Japan's social welfare system.

- Clarification of the Public Assistance Act's Scope: The ruling provided a definitive judicial interpretation that the Seikatsu Hogo Hō, based on its explicit reference to "nationals," does not legally entitle non-Japanese citizens to protection. This confirmed the legal basis for excluding foreigners from the Act's de jure coverage, even if administrative practice sometimes extended aid de facto.

- Reinforcement of Legislative Supremacy in Social Security Scope: The decision strongly reaffirmed the principle of broad legislative discretion in defining the beneficiaries of Japan's social security system. The Court made it clear that extending core welfare benefits like public assistance to non-nationals, especially those without legal status, is fundamentally a policy choice for the Diet, not a constitutional mandate enforceable by the courts.

- Limited Interpretation of Article 25 for Non-Nationals: The ruling cemented the view that Article 25's guarantee of minimum standards primarily imposes duties on the state regarding its own nationals. While foreigners residing legally in Japan enjoy many constitutional rights, Article 25 does not appear to grant them, let alone undocumented individuals, a direct, actionable right to specific social security benefits against the state. Their access to the social safety net remains largely dependent on legislative grace or specific treaty obligations.

- Humanitarian Concerns vs. Legal Boundaries: The case starkly highlights the tension between the legal framework and humanitarian needs. Denying assistance, even for emergency medical care resulting from an accident within Japan, to someone solely based on their irregular residency status raises significant ethical questions. The Court acknowledged the existence of the physician's duty to treat (Medical Practitioners Act) but framed the funding of such treatment through the Public Assistance Act as a separate legislative policy choice. This leaves open practical questions about how emergency care for uninsured, undocumented individuals is actually financed, often relying on hospital write-offs, limited local government schemes, or charitable aid.

- Undocumented Status as a Key Factor: The judgment repeatedly refers to the appellant as a "fuhō zanryūsha" (illegal overstayer). This status appears central to the Court's finding that the exclusion was constitutionally permissible under both Article 25 and Article 14. While the reasoning on Article 14 was brief, the implication is that the lack of legal residency status provides a rational basis for differential treatment in this context. International bodies often prefer terms like "irregular" or "undocumented" to avoid the stigma of "illegal," highlighting the different perspectives on this issue.

- Relation to Administrative Practice and Later Rulings: The judgment focused on the letter of the law, seemingly giving less weight to the historical administrative practice of quasi-application (jun'yō). This practice, though restricted over time, acknowledged a need to support destitute foreigners. The Supreme Court later revisited the issue of foreigners and public assistance in the Ōita City case (Supreme Court, 2014). In that case, involving legally resident foreigners, the Court reaffirmed that foreigners have no legal right to claim benefits under the Act itself. However, it acknowledged that the long-standing administrative practice of applying the Act mutatis mutandis to legally resident foreigners in need created a factual situation where such individuals might receive protection as a matter of administrative policy, potentially subject to review if arbitrarily denied within the scope of that established practice. The 2001 ruling thus stands as clarifying the lack of statutory entitlement, particularly for undocumented residents, while the 2014 ruling addressed the legal status of the administrative quasi-application for documented residents.

Conclusion

The 2001 Supreme Court decision firmly established that Japan's Public Assistance Act, as written, does not legally oblige the state to provide protection to foreign nationals, particularly those residing without legal status. The Court held that the exclusion of undocumented residents from this core social safety net program is a matter within the broad legislative discretion afforded by the Constitution under Article 25 (right to minimum standards) and does not constitute unreasonable discrimination under Article 14 (equality), even in cases involving emergency medical needs. The ruling underscores the principle of legislative supremacy in defining the scope of social security beneficiaries in Japan and limits the judiciary's role in mandating extensions of coverage to non-nationals based directly on constitutional rights. While addressing the legal question, the case leaves open the ongoing policy and ethical challenges related to ensuring basic humanitarian support for all individuals within Japan's borders, regardless of their residency status.