Defining the Boundaries of Tax Investigations in Japan: The 1973 Arakawa Minsho Case

Case Title: Income Tax Act Violation Case

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Decision Date: July 10, 1973

Case Number: 1970 (A) No. 2339

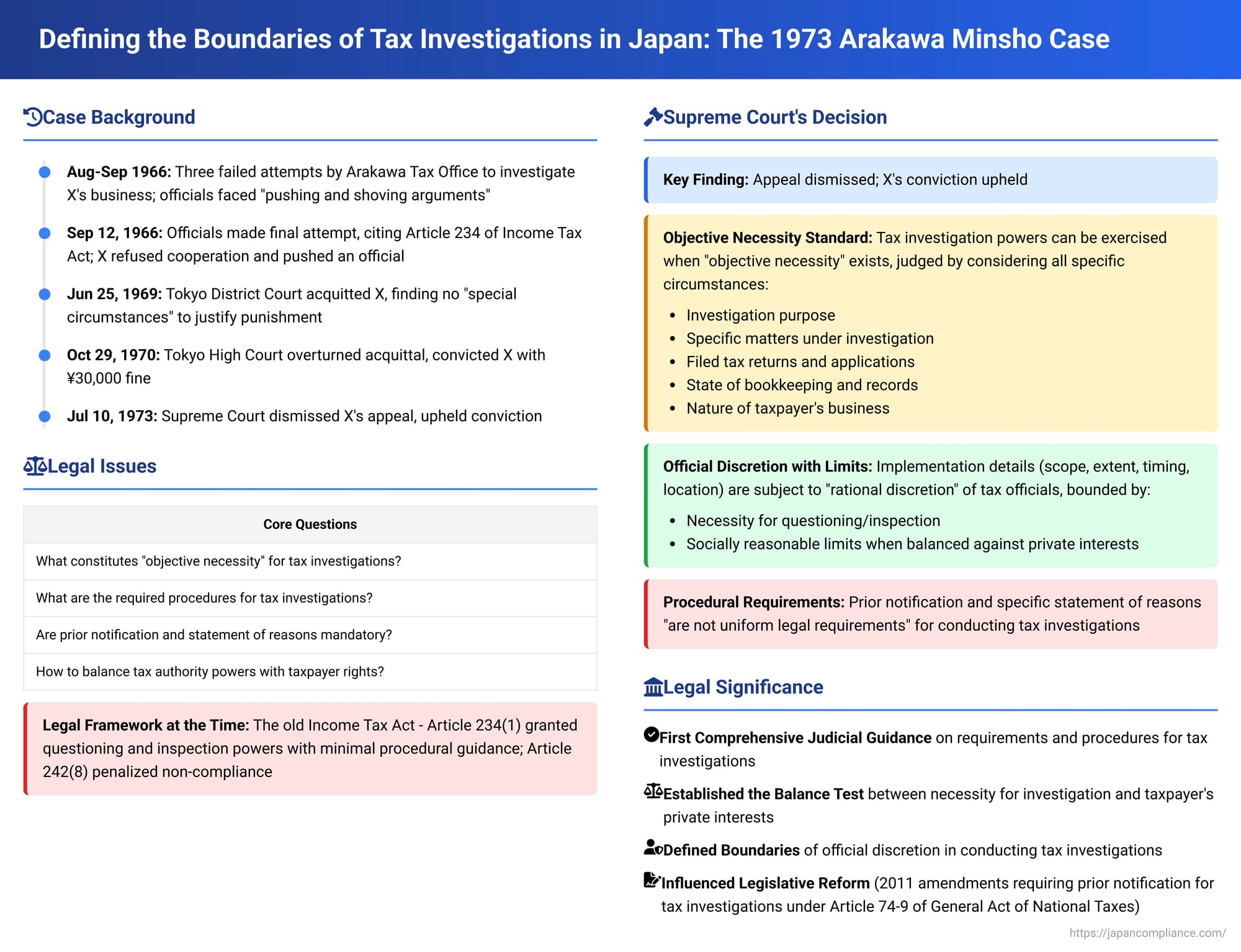

This 1973 Supreme Court decision, often referred to as the "Arakawa Minsho Case," stands as a seminal ruling in Japanese administrative law, offering the first comprehensive judicial guidance on the requirements and procedures governing tax investigations. The case involved a taxpayer, X, who was prosecuted for refusing to cooperate with tax officials. His appeal challenged the scope and limits of the questioning and inspection powers granted to tax authorities under the then-operative Income Tax Act, raising critical questions about concepts like "objective necessity" for investigations and the mandatory nature of procedural safeguards such as prior notification and the provision of specific reasons for an audit.

Background: A Standoff Between Taxpayer and Tax Office

The defendant, X, was the proprietor of a press processing business located in Arakawa Ward, Tokyo. The Arakawa Tax Office came to suspect that X had underreported his income for the taxable year 1965 and determined that an investigation was necessary.

Repeated Attempts and Escalation:

Between August and September 1966, officials from the tax office made three visits to X's premises to conduct the investigation. However, each attempt devolved into what the judgment describes as "pushing and shoving arguments" (oshimondō) with X and others present, preventing the officials from achieving their investigative objectives.

The situation culminated on September 12, 1966, when tax officials made another visit to X's premises. On this occasion, they explicitly informed X of the necessity to investigate his 1965 income pursuant to Article 234 of the Income Tax Act (a provision granting powers of questioning and inspection, broadly equivalent to Article 74-2 of the current General Act of National Taxes). They also warned him that failure to cooperate with the investigation was a punishable offense. The officials then stated their intention to examine X's books and documents and to inspect his factory.

X and others with him responded defiantly, shouting remarks such as, "It's no use talking, just leave!", "We can't answer unless our livelihood is guaranteed!", and "We won't allow the investigation!". Furthermore, X physically pushed one of the officials in the lower back, thereby overtly refusing the investigation.

Criminal Charges:

As a result of this refusal, X was prosecuted under Article 242, item 8 of the old Income Tax Act (a provision penalizing non-compliance, broadly equivalent to Article 128, item 2 of the current General Act of National Taxes) for refusal to answer questions and refusal of inspection.

Lower Court Proceedings:

The path through the lower courts saw divergent outcomes:

- Tokyo District Court (First Instance, June 25, 1969): This court acquitted X. Its reasoning was that an offense under Article 242, item 8 of the Income Tax Act is established only when there is not only a "rational necessity" for the questioning or inspection but also "special circumstances" such that punishing the non-compliance or refusal would not be deemed unreasonable. The District Court found that such special circumstances were not present in X's case.

- Tokyo High Court (Appeal Court, October 29, 1970): The High Court overturned the District Court's acquittal and convicted X, imposing a fine of 30,000 yen. The High Court found that the tax officials' request for inspection was not particularly improper or illegal when considered in light of Article 234, Paragraph 1 of the Income Tax Act. It further stated that it could find no grounds to justify X's refusal of the inspection and, significantly, asserted that there were indeed circumstances present that would make punishing X not unreasonable—essentially finding the "special circumstances" that the first instance court had deemed absent. X subsequently appealed this conviction to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Setting the Standard

The Supreme Court's Third Petty Bench, in its decision on July 10, 1973, dismissed X's appeal, thereby upholding his conviction. More importantly, the Court used this opportunity to articulate its interpretation of the questioning and inspection powers under Article 234, Paragraph 1 of the old Income Tax Act, establishing key principles for tax investigations.

The Court's Interpretation of Questioning and Inspection Powers:

The Supreme Court held that Article 234, Paragraph 1, was intended to grant authority to officials of the National Tax Agency, Regional Taxation Bureaus, or local Tax Offices who possess investigative powers, under the following conditions:

- Objective Necessity: Such powers can be exercised when, after considering all specific circumstances of the case – including the purpose of the investigation, the specific matters to be investigated, the form and content of any tax applications or returns already filed, the state of the taxpayer's bookkeeping and record preservation, the nature of the taxpayer's business, and other relevant factors – it is judged that there exists an objective necessity for the investigation.

- Method of Official Investigation: When such objective necessity is determined, these officials are authorized, as one method of conducting their official investigation, to question the persons specified in the various items of Article 234, Paragraph 1, or to inspect their business-related books, documents, and any other items that have a connection to the matters under investigation.

Discretion Regarding Implementation Details:

The Court then addressed the practical aspects of conducting these investigations—such as the scope, extent, timing, and location of questioning and inspection—for which the statute did not provide specific, detailed rules:

- These implementation details are entrusted to the rational discretion (or "rational choice" - gōriteki na sentaku) of the authorized tax officials.

- However, this discretion is not unfettered. It is subject to two crucial limitations:

- There must be a necessity for the questioning or inspection, as defined above (i.e., objective necessity based on all circumstances).

- The exercise of these powers must remain within limits that are socially reasonable (or "socially accepted as appropriate" - shakai tsūnenjō sōtō na gendo) when balancing this necessity against the private interests of the party being investigated.

Specific Procedural Issues Addressed:

The Supreme Court also clarified several specific procedural points that were contentious:

- Timing of Investigations: Questioning and inspection are not legally prohibited even if conducted before the end of the calendar year (for individual income tax) or before the statutory period for filing a final tax return has passed.

- Prior Notification and Statement of Reasons: The Court explicitly stated that prior notification of the date, time, and place of an investigation, and the individual, specific notification of the reasons and necessity for the investigation, are not uniform legal requirements (hōritsujō ichiritsu no yōken) for conducting such questioning or inspection.

Interpretation of "Person Liable for Tax Payment":

Finally, the Court provided an interpretation of the term "person liable for tax payment" as used in Article 234, Paragraph 1, which is a key trigger for the application of these investigative powers:

- Considering that the purpose of the questioning and inspection system is to achieve fair and equitable taxation, and that official investigations may often need to be conducted before tax liability is definitively finalized, this term should be understood broadly.

- It includes not only those whose tax liability has already been objectively established because all legal requirements for taxation have been met, and who have not yet completed payment of the correctly assessed tax amount.

- It also encompasses those who, during an ongoing taxable year, have generated income that will form the basis of taxation and who will, as a result, ultimately bear a tax liability in the future.

- Furthermore, the term "persons deemed liable for tax payment" refers to individuals who are reasonably inferred by authorized tax officials, based on their judgment, to fall into either of the aforementioned categories of taxpayers.

Based on these interpretations, the Supreme Court found no error in the High Court's application of the law to the facts of X's case and dismissed the appeal.

Analysis and Lasting Significance of the Decision

The Arakawa Minsho Case decision is a landmark in Japanese administrative law for several reasons:

1. Establishing a Benchmark for Tax Investigations:

This was the first time the Supreme Court laid down guiding principles regarding the substantive requirements (like "objective necessity") and procedural aspects (like prior notice and statement of reasons) for tax investigations. It, along with the nearly contemporaneous Kawasaki Minsho Case (Supreme Court, Grand Bench, November 22, 1972, which dealt more with the constitutional implications of warrantless tax inspections), significantly shaped the legal understanding of not only tax audits but also administrative investigations more broadly.

2. Addressing the Under-Regulation of Administrative Investigations:

At the time of this decision, the legal framework governing administrative investigations in Japan was relatively sparse. Article 234(1) of the old Income Tax Act simply stated that officials could question and inspect if "necessary," and Article 242(8) provided penalties for refusal or obstruction. (These provisions were later consolidated and refined in the General Act of National Taxes).

This type of investigation, where compliance is not forced by direct physical power but rather through the threat of penalties for non-cooperation, is sometimes termed an "indirectly compulsory investigation". While many such investigative powers exist across various Japanese laws, specific procedural rules were often lacking. Some statutes did include provisions for prior notice or the opportunity to submit opinions (e.g., the Statistics Act, the Basic Act on Food, Agriculture and Rural Areas), but for many, including tax investigations at the time, the legal provisions were limited to the basic grant of power, a confirmation that the power was not for criminal investigation purposes, a requirement for officials to carry identification, and penalty clauses.

Furthermore, the Administrative Procedure Act, enacted later, does not set out general procedural rules for administrative investigations. In fact, it largely excludes "dispositions directly aimed at collecting information necessary for the performance of duties" and "administrative guidance" from many of its key procedural requirements. Factual acts like on-site inspections are also excluded from the definition of "adverse dispositions" that trigger certain procedural rights. This general lack of detailed statutory regulation for administrative investigations often led to uncertainty and debate about the necessary legal controls. The Arakawa Minsho decision was therefore pivotal in affirming that such investigations are indeed subject to a legal framework, albeit one granting considerable discretion.

3. Judicial Interpretation of Key Concepts:

- (a) "Objective Necessity" for Investigation:

The Court's standard of "objective necessity... judged considering all specific circumstances" requires that investigations are not arbitrary or based on mere whim. While the decision itself doesn't list exhaustive criteria, it implies that concrete grounds for suspicion are needed. For instance, if, as was noted in the lower court proceedings of this case, there were specific reasons to suspect underreporting (e.g., significant discrepancies compared to previous years' income, unexplained changes in the number of business dependents), these could constitute objective necessity. The necessity for "reverse investigations" (hansomen chōsa), which involve investigating a taxpayer’s business partners or other third parties, would likely require an even more cautious assessment, balancing the investigative need against the third party's private interests. - (b) "Manner of Investigation" (Scope, Extent, Timing, Location):

The decision allows tax officials "rational discretion" in how they conduct investigations, provided the investigation is necessary and stays within "socially reasonable limits when balancing against the private interests of the party". This abstract standard has been criticized for potentially allowing too much leeway to officials. However, it also implicitly incorporates the proportionality principle: the scope and intensity of an investigation should be no more than necessary to achieve its legitimate objective.

Post-1973 lower court cases have occasionally found tax investigations to be illegal based on their manner. Examples include:- An tax officer unlatching an inner door of a shop without permission merely to check if anyone was present (Supreme Court, 1988, finding this outside the scope of legitimate questioning/inspection powers and upholding a damages award).

- An officer entering a private residential area of a building without consent (Osaka High Court, 1998, leading to a damages award).

- An officer taking photographs inside a warehouse without consent after being asked to leave (Kobe District Court, 2013, found illegal in a damages claim).

- Continuing an investigation despite the taxpayer having an urgent business matter to attend to, or attempting an investigation by visiting just before work hours without any prior contact, have also been deemed to exceed permissible limits (Kobe District Court, 1976).

These examples help delineate the boundaries of "socially reasonable limits," though further case law development is needed for clearer categorization.

- (c) Prior Notification and Statement of Reasons:

The Court’s statement that these are "not uniform legal requirements" was significant. It could be interpreted as giving broad permission for investigations without such prior steps. However, some commentators suggested it also implied that in certain circumstances, prior notice or a statement of reasons might be necessary, though the decision didn't specify when.

While the nature of some investigations might make prior notification counterproductive (e.g., risk of evidence destruction), due process considerations highlighted the desirability of clearer procedural rules. This eventually led to legislative change. The 2011 amendments to the General Act of National Taxes (effective from January 1, 2013) consolidated various provisions related to tax investigations into a new Chapter 7-2, titled "Tax Investigations".

Crucially, these amendments newly mandated prior notification for on-site tax investigations (Article 74-9). This article requires tax officials to inform the taxpayer (or their tax agent, etc.) in advance about the intended start date and time, the place to be investigated, the purpose of the investigation, the tax types and periods covered, and the books/documents to be inspected, among other things.

However, this requirement for prior notification is not absolute. Article 74-10 of the amended Act provides exceptions, allowing officials to dispense with prior notice if they believe that giving notice would facilitate obstructive actions by the taxpayer (such as destroying or concealing records) or would otherwise hinder the accurate assessment of tax liability or the proper conduct of the investigation. The application of this exception is determined on a case-by-case basis and remains subject to judicial review, with its interpretation and practical application continuing to be shaped by ongoing case law. Recent lower court decisions, for example, have affirmed that oral prior notification can be valid under Article 74-9(1) and that investigation staff can provide such notice as auxiliary agents of the tax office chief.

It is important to note that the 2011 amendments did not introduce a general requirement for tax officials to provide a specific statement of the reasons for initiating an investigation. Therefore, the legal position on this particular point likely continues to be governed by the principles set out in the 1973 Arakawa Minsho decision – i.e., it is not a uniform legal requirement.

Continuing Relevance:

The Arakawa Minsho Case, despite subsequent legislative developments, remains a foundational judgment. It affirmed that even indirectly compulsory administrative investigations are subject to legal principles of necessity and proportionality (social reasonableness). While it granted considerable discretion to tax authorities regarding the conduct of investigations at the time, it also opened the door for greater judicial scrutiny and contributed to the impetus for later legislative reforms aimed at enhancing procedural fairness and taxpayer rights in the context of tax audits. The decision continues to be a key reference point for understanding the delicate balance between the state's need to effectively administer its tax system and its obligation to respect the rights and interests of its citizens.