Defining the Boundaries: Japan's Supreme Court on Delegating Rate-Setting Powers to Cabinet Orders

A First Petty Bench Ruling from December 14, 2015

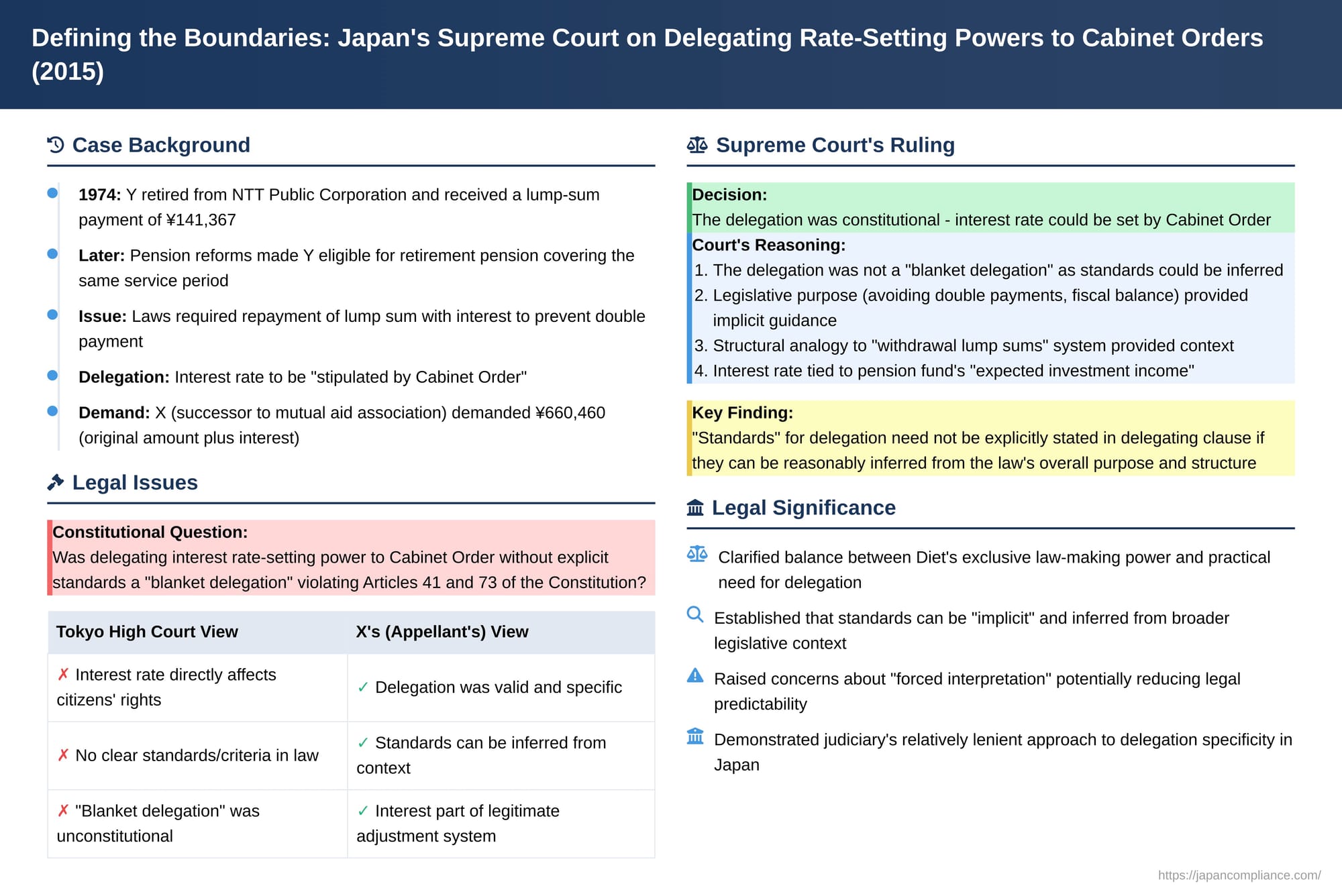

Modern governance often requires legislatures to delegate some law-making power to executive bodies to handle complex, technical, or rapidly changing details. However, this practice raises fundamental constitutional questions: How much power can be delegated, and how specific must the primary legislation (the "delegating law") be in guiding the exercise of that delegated authority? A decision by the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan on December 14, 2015 (Heisei 26 (O) No. 77, (Ju) No. 93), addressed these questions in the context of a dispute over the repayment of pension-related lump sums, where the interest rate for repayment was determined by a Cabinet Order based on a legislative delegation.

The Case of Y and the Repayment Demand

The case involved an individual, Y, who had retired from the former Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Public Corporation (the former NTT Public Corp.) in 1974. Upon retirement, Y received a lump-sum payment of 141,367 yen from the mutual aid association associated with the public corporation.

Years later, Japan's pension laws underwent significant reforms. These reforms led to a situation where individuals like Y, who had received such lump sums, later became eligible for a new retirement mutual aid pension that covered the same period of service for which the lump sum was paid. To prevent what was seen as a double payment for the same service period, a system was introduced requiring the repayment of the original lump sum. This repayment wasn't just the principal amount; it also included an amount equivalent to accrued interest (利子相当額 - rishi sōtōgaku). The relevant laws—specifically, Supplementary Provision Article 12-12 of the National Public Service Mutual Aid Association Act (国公共済法 - Koku-Kō Kyōsai Hō, before its 2012 amendment) and transitional measures in Supplementary Provision Article 30 of the Act to Amend Parts of the Employees' Pension Insurance Act, etc. (Pension Reform Act of 1996) —stipulated that the interest should be calculated using a compound interest method. Crucially, these laws stated that "the interest rate shall be stipulated by Cabinet Order".

When Y became eligible for the pension upon reaching age 60, X, the entity that succeeded the rights and obligations of the original mutual aid association, demanded that Y repay the lump sum with the accrued interest, totaling 660,460 yen, plus charges for late payment.

The Legal Challenge: A "Blanket Delegation"?

The Tokyo High Court (the second instance court) had partially sided with Y. It ruled that the interest rate for such repayments directly affected citizens' rights and financial obligations and was therefore a "legal matter" (hōritsu jikō) that, if delegated to a Cabinet Order, required the delegating law to provide clear standards or criteria—such as factors to be considered in setting the rate, or an upper limit. The High Court found that the delegating statutes in question failed to provide such specific limitations and instead constituted a "blanket and comprehensive delegation" (hakuchi de hōkatsutekina inin) of power to the Cabinet Order. Consequently, it deemed this delegation unconstitutional and invalid, thereby nullifying the Cabinet Order's provisions setting the interest rate (specifically, Article 4(2) of Cabinet Order No. 86 of 1997) and rejecting X's claim for the interest portion of the repayment. X then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision of December 14, 2015

The Supreme Court's First Petty Bench reversed the Tokyo High Court's decision regarding the interest and upheld X's claim in its entirety.

Finding Implicit Standards in the Delegation:

The core of the Supreme Court's reasoning was that the delegation of power to the Cabinet Order to set the interest rate was not an impermissible "blanket delegation". The Court found that the delegating laws, when read in their entirety and in light of their purpose, provided sufficient implicit guidance:

- Legislative Purpose: The Court emphasized that the system requiring repayment of the lump sum with interest was established as an "adjustment measure to avoid double payment" for the same period of service. It was also aimed at maintaining the "financial equilibrium" of the pension system.

- Analogy to Withdrawal Lump Sums: The method of calculating the repayment, particularly the addition of interest, was analogous to the calculation for "withdrawal lump sums" (脱退一時金 - dattai ichijikin) under a previous, related system. In that system, the interest added was explicitly tied to expected investment income of the pension funds, and the rate (e.g., 5.5% per annum) was set by Cabinet Order based on this principle.

- Implicit Guidance: Given this legislative purpose (avoiding double payments, ensuring fiscal balance) and the structural analogy to the withdrawal lump sum system, the Supreme Court interpreted the delegating provisions as intending for the interest rate on the repaid lump sum to be set by Cabinet Order "in consideration of equilibrium with the interest rate related to expected investment income" (予定運用収入に係る利率との均衡を考慮して定められる利率). This provided an implicit, yet discernible, standard.

- No Constitutional Violation: Because this guiding principle could be reasonably inferred from the overall legislative scheme, the delegation was not a "blanket" one. Therefore, it did not violate Article 41 of the Constitution (which establishes the Diet as the "sole law-making organ") or Article 73, item 6 (which requires specific delegation by law for Cabinet Orders to, for example, establish penal provisions, a principle extended to other delegations affecting citizens' rights). The Court referenced prior Grand Bench precedents to support its stance on permissible delegation.

The High Court's Misinterpretation (According to the Supreme Court):

The Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in its understanding of the repayment scheme. The High Court had characterized it as a retroactive nullification of the original lump sum payment, akin to the repayment of unjust enrichment under the Civil Code. The Supreme Court clarified that the repayment was an "adjustment measure" related to future pension entitlements to prevent double benefits, not a clawback of an invalid past payment. This difference in characterization was crucial, as it meant the statutory default interest rate for civil claims (under Civil Code Article 404) was not the presumptive benchmark that the High Court thought it was. The High Court also erred, in the Supreme Court's view, by concluding that the delegation was an impermissible blanket one.

Legality of the Cabinet Order's Interest Rate:

The Supreme Court noted that the interest rates specified in the relevant Cabinet Order (e.g., 5.5% per annum for the period until March 2001, and 4% per annum for April 2001 to March 2005) were indeed linked to the historical expected investment income rates of the pension funds. As such, these rates were consistent with the delegating laws' intent and were not deemed unreasonable or unlawful.

Understanding Delegated Legislation in Japan

This case touches upon fundamental principles of Japan's constitutional order regarding law-making:

- Article 41 of the Constitution designates the National Diet as the "sole law-making organ of the State". This establishes the principle of "Diet-centered legislation" (国会中心立法の原則 - kokkai chūshin rippō no gensoku), meaning the Diet has a monopoly on primary legislative power.

- Article 73, item 6 of the Constitution outlines the Cabinet's functions, including the "enactment of cabinet orders to execute the provisions of this Constitution and of the law." However, it contains a crucial proviso: "It cannot, however, include penal provisions in such cabinet orders unless authorized by such law." While this proviso directly addresses penal provisions, it's judicially interpreted as supporting the broader principle that any delegation of power to Cabinet Orders to define matters affecting citizens' rights or obligations must be specifically authorized by a Diet-enacted law.

- Necessity of Delegation: Despite the Diet-centered principle, the complexities of modern society and governance make some degree of legislative delegation to the executive branch a practical necessity. This is due to factors like the sheer volume of legislative work, the need for specialized technical expertise, the unpredictability of certain situations, the requirement for swift and flexible responses, and the existence of administrative areas best kept politically neutral. Such delegation is often seen as "naturally permissible as a matter of common sense" (jōri jō tōzen ni yōnin sareru mono).

- Limits on Delegation: This practical necessity does not mean unlimited delegation is allowed. To remain consistent with Article 41, any delegation must be "individual and specific" (kobetsuteki, gutaiteki inin) rather than general or "blanket" (hakuchi). The empowering (delegating) law enacted by the Diet should itself establish the main principles and provide the "purpose" (目的 - mokuteki) and "standards/criteria" (基準 - kijun) that the subordinate legislation (e.g., a Cabinet Order) must follow.

- Inferring Standards: Japanese courts, including the Supreme Court in previous landmark cases, have established that these guiding "purposes" and "standards" do not necessarily have to be explicitly spelled out in the precise delegating clause of the statute. They can be "reasonably derived from other provisions of the said law or from the law as a whole". This approach, while allowing for necessary flexibility, also introduces a degree of ambiguity, making the assessment of a delegation's validity often a matter of interpretation and degree.

Critical Perspectives on the Judgment

While the Supreme Court found the delegation in this case constitutional, some legal analysis (as reflected in the provided source material's commentary) raises critical points:

- The connection between the stated legislative purpose (avoiding double payments, ensuring fiscal balance) and the specific interest rate tied to "expected investment income" might be seen as a logical leap if not explicitly stated or strongly implied in the delegating statutes themselves. The purpose of avoiding double payment does not inherently dictate the rate of interest that should be applied to the repayment.

- Relying on past administrative practices (like the 5.5% rate used for a different type of lump sum, the "withdrawal lump sum") as a primary basis for interpreting the legislative criteria embedded in the delegating law can be problematic from a rule-of-law perspective, which emphasizes that laws should be clear on their face.

- Similarly, general provisions about maintaining the fiscal balance of pension funds (like Article 99(1)(ii) of the Koku-Kō Kyōsai Hō at the time) might not, on their own, create a sufficiently clear and direct legal basis for imposing an obligation on individual retirees to repay their lump sums with interest calculated at the pension fund's internal expected investment rate.

- The argument is made that even a comprehensive review of the delegating laws does not readily reveal an unambiguous "standard" for the specific interest calculation method (including the starting point for interest accrual, the use of phased rates, and the compound interest method) being directly tied to the pension fund's expected investment returns.

- There's a concern that the Supreme Court might have engaged in a "forced limited interpretation" (gōin na gentei kaishaku) of the delegating statutes to uphold their constitutionality, potentially at the cost of legal predictability. If the meaning and scope of a delegation are only discernible through such intricate judicial construction, it challenges the ideal that laws should be readily understandable to those they affect.

- A broader point is that Japanese judicial review concerning the specificity of legislative delegation has historically tended to be somewhat lenient. It's argued that for matters that directly and significantly impact citizens' rights and financial obligations—as was the case here—the guiding "standards" in the delegating law should perhaps be defined with even greater clarity and rigor by the Diet itself.

Conclusion

The 2015 Supreme Court decision in the retirement lump sum repayment case is an important illustration of how Japanese law navigates the persistent tension between the constitutional principle of Diet-centered law-making and the practical need for administrative bodies to handle detailed rulemaking. By finding implicit standards within the broader legislative framework, the Court upheld the delegation of power to set a crucial interest rate via Cabinet Order. This case underscores the judiciary's role in interpreting the permissible boundaries of such delegation, affirming that while "blanket delegation" is unconstitutional, the guiding principles from the Diet need not always be explicit in the delegating clause itself, provided they can be reasonably discerned from the law's overall purpose and structure. However, it also fuels the ongoing debate about the degree of clarity required in delegating statutes, especially when substantial financial obligations of citizens are at stake, and whether judicial interpretation sometimes stretches to find specificity where the legislature might have been more explicit.