Defining "Tax": Japanese Supreme Court on National Health Insurance Premiums and Constitutional Scrutiny

Judgment Date: March 1, 2006

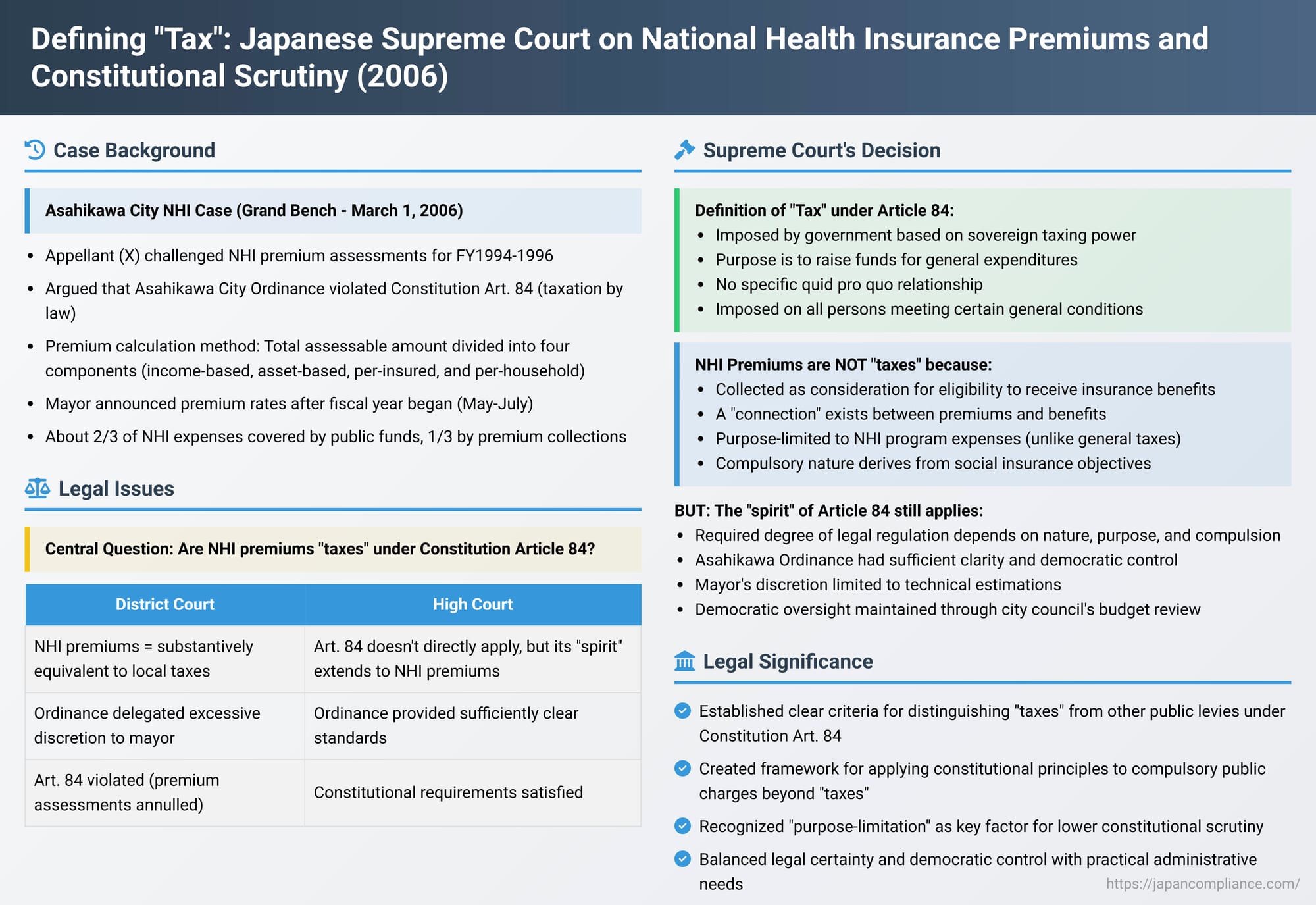

In a landmark decision with profound implications for the understanding of "taxes" under the Japanese Constitution and the scope of parliamentary control over public levies, the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan ruled on the nature of National Health Insurance (NHI) premiums. The case, originating from Asahikawa City, questioned whether these premiums constitute "taxes" subject to the strictures of Article 84 of the Constitution, which mandates that all taxation be based on law. The Court concluded that NHI premiums are not "taxes" in this constitutional sense but are nevertheless subject to the "spirit" of Article 84, requiring a degree of legislative control appropriate to their nature.

Background of the Asahikawa City Case

The appellant, X, a head of household enrolled in the National Health Insurance plan administered by Asahikawa City (Y1), challenged the legality of NHI premium assessments levied for the fiscal years 1994 through 1996. X argued that the provisions within the Asahikawa City National Health Insurance Ordinance (referred to as "the Ordinance") for determining these premiums were unconstitutional. The core of X's claim was that the Ordinance violated Article 84 of the Constitution, which enshrines the principle of "taxation by law," requiring that taxable items and the method of their calculation be clearly and definitively established by statute (or by ordinance based on statutory delegation).

Under the National Health Insurance Act, municipalities like Asahikawa City are insurers. They are mandated to provide necessary insurance benefits for illness, injury, childbirth, or death of the insured. To fund these benefits, municipalities can choose to collect either NHI premiums or a specific NHI tax. Asahikawa City had opted for the premium system.

The Ordinance in question stipulated a method for calculating the total amount of premiums to be assessed on insured households (the "total assessable amount"). This amount was determined by taking the estimated total expenses necessary for the NHI program for the fiscal year and subtracting the estimated total revenues from sources other than premiums. These other revenues included national government subsidies and financial transfers from the city's general account. Notably, for the fiscal years in question, such public funds constituted approximately two-thirds of the revenue in Asahikawa City's NHI special account, with premium collections making up the remaining one-third.

This "total assessable amount" was then divided into four components for individual household assessment:

- An income-based portion (所得割総額)

- An asset-based portion (資産割総額)

- A per-insured flat-rate portion (被保険者均等割総額)

- A per-household flat-rate portion (世帯別平等割総額)

The Ordinance specified the ratios for this division and the method for calculating the premium rate for each component. For example, the income-based premium rate was derived by dividing the total income-based assessable amount by the aggregate total income (after basic deductions) of all eligible insured persons. The actual premium rates were determined by the Mayor of Asahikawa City (Y2) and publicly announced after the fiscal year began on April 1st. For the years in contention, these announcements occurred between late May and early July.

X also challenged the denial of premium reductions or exemptions by the Mayor of Asahikawa City.

Lower Court Proceedings

The Asahikawa District Court, the court of first instance, sided with X regarding the premium assessment. It held that NHI premiums were, in substance, equivalent to local taxes, citing the compulsory nature of NHI enrollment, the forced collection of premiums, and the fact that the direct quid pro quo relationship between premiums paid and benefits received was diluted by significant public funding. The District Court found that the Ordinance delegated excessive discretion to the city in determining the total assessable amount, thereby violating the principle of taxation by law under Article 84, and consequently annulled the premium assessments.

The Sapporo High Court, on appeal, reversed this decision. While it disagreed that Article 84 directly applied to NHI premiums, it conceded that the "spirit" or underlying principles of Article 84 should extend to them. The High Court found that the Ordinance, in conjunction with the National Health Insurance Act, did provide sufficiently clear and specific standards for the Mayor's determination of premium rates. It further held that the public notification of these rates satisfied the constitutional requirements of clarity and legality embodied in the spirit of Article 84. X then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Adjudication

The Supreme Court meticulously examined the arguments, focusing on the fundamental question of whether NHI premiums are "taxes" within the meaning of Article 84 of the Constitution.

Defining "Tax" under Article 84

The Court began by defining what constitutes "tax" (租税 - sozei) for the purposes of Article 84. It stated that a monetary charge falls under this definition if it meets the following criteria:

- It is imposed by the national or a local government based on its sovereign taxing power.

- Its purpose is to raise funds for the government's general expenditures.

- It is levied not as a specific quid pro quo or consideration for a particular service or benefit received by the payer.

- It is imposed on all persons who meet certain prescribed general conditions.

National Health Insurance Premiums: Not "Taxes"

Applying this definition, the Court concluded that NHI premiums collected by municipalities are distinct from taxes and therefore Article 84 does not directly apply to them. The Court reasoned:

- Quid Pro Quo Relationship: NHI premiums are collected as consideration for the eligibility to receive insurance benefits under the NHI program. This establishes a link between the payment and the potential benefit.

- Impact of Public Funding: The fact that approximately two-thirds of Asahikawa City's NHI program expenses were covered by public funds (national subsidies, transfers from general accounts, etc.) does not sever this fundamental "connection" (けん連性 - kenrensei) between the premiums paid by the insured and their status of being eligible to receive benefits. The Court preferred the term "connection" over a stricter interpretation of "quid pro quo" (対価性 - taikasei), implying that a direct quantitative correspondence between individual premiums and benefits is not required.

- Compulsory Nature: The compulsory enrollment in NHI and the mandatory collection of premiums derive from the intrinsic nature and objectives of social insurance. Social insurance aims to cover as many individuals exposed to certain risks as possible and to mutually share the economic losses arising from insured events (like illness) among all participants. This compulsory aspect serves the social insurance goal of risk pooling.

The Court did, however, note an important distinction: if a municipality chooses to fund its NHI program through a "National Health Insurance Tax" (as permitted by the Local Tax Act), then Article 84 would apply. This is because, despite its purpose being tied to NHI and its collection being for a benefit, the levy takes the form of a tax, thereby bringing it under constitutional tax law principles.

The "Spirit" of Article 84 and Its Reach to Non-Tax Levies

Despite finding NHI premiums not to be "taxes," the Court did not entirely dismiss the relevance of Article 84. It elaborated:

- Article 84, by mandating that tax assessment criteria and procedures be clearly defined by law, is a specific and stricter manifestation of a broader legal principle: that any imposition of duties or restriction of rights upon citizens requires a legal basis.

- Therefore, public levies other than taxes are not automatically exempt from this underlying principle simply because they do not meet the strict definition of "tax" under Article 84.

- For public charges that bear a resemblance to taxes in certain aspects, such as the degree of compulsion in their assessment and collection, the "spirit" or "purport" (趣旨 - shushi) of Article 84 should be considered to apply.

However, the Court cautioned that even when the spirit of Article 84 applies, the specific requirements for legal regulation—such as how explicitly the assessment criteria must be laid down in a law or ordinance—are not identical to those for taxes. Instead, the required level of regulatory detail must be determined by comprehensively considering various factors:

* The nature of the specific public levy.

* The purpose for which it is assessed and collected.

* The degree of compulsion involved.

Applying the "Spirit" of Article 84 to NHI Premiums

The Court found that NHI premiums, even when collected as "premiums" rather than "taxes," do resemble taxes in their compulsory enrollment and collection, and thus the spirit of Article 84 extends to them.

Crucially, however, the Court highlighted a key differentiating factor: the use of NHI premiums is specifically restricted to covering the expenses of the National Health Insurance program (国民健康保険事業に要する費用に限定されている). This "purpose-limitation" is a significant distinction from general taxes, which typically flow into the general treasury for unrestricted public expenditure.

Given this, the Court stated that the necessary degree of clarity for defining assessment criteria in an ordinance (delegated under Article 81 of the NHI Act) must be judged by considering not only the degree of compulsion but also the specific objectives and characteristics of the National Health Insurance system as a form of social insurance.

Evaluating the Asahikawa City Ordinance

The Court then scrutinized the Asahikawa City Ordinance based on these principles:

- Delegation and Calculation Basis: The Ordinance (Article 12, Paragraph 3) delegates the determination of premium rates to the Mayor, who then announces them by public notice. Since the premium rates are automatically calculable once the total assessable amount is fixed, the Ordinance effectively delegates the determination of this total amount to the Mayor as well.

Article 8 of the Ordinance defines the total assessable amount as the sum derived by taking the projected amount of expenses listed in Article 8, Item 1, subtracting the projected amount of revenues (excluding premiums) listed in Article 8, Item 2, and then adjusting this figure based on a "standard" or criterion. The Court interpreted this "standard" to mean adjusting the net shortfall (projected expenses minus non-premium projected revenues) by a projected collection rate. This allows the city to assess enough to cover expected shortfalls due to uncollectable premiums.

The Court found this method of calculating the total assessable amount—aimed at covering the net financial needs of the NHI program for that fiscal year—to be consistent with the mutual aid principle underlying NHI and its purpose of funding necessary program expenses (as per Article 76 of the NHI Act). Article 8 of the Ordinance clearly specified the detailed items to be included in these projected expenses and revenues. - Mayor's Discretion and Democratic Control: The Court acknowledged that estimating these projected expenses, revenues, and the collection rate involves specialized and technical considerations. It held that entrusting these estimations to the reasonable judgment of the Mayor was permissible.

Importantly, the Court found that democratic control over these estimations is maintained because the NHI program operates under a special account, and its budget and financial settlements are subject to deliberation and approval by the city council. This oversight by the elected council ensures a level of democratic accountability. - Compliance with Law and Constitution: The Court concluded that the Ordinance, by establishing a clear basis for calculating the total assessable premium amount and then delegating to the Mayor the determination of rates based on these criteria and their subsequent public notification, does not violate Article 81 of the National Health Insurance Act (which requires ordinances to set forth premium matters in accordance with standards set by cabinet order). Furthermore, this framework does not contravene the spirit of Article 84 of the Constitution.

- Timing of Rate Announcement: The Court also addressed the fact that the premium rates were announced after the official assessment date (April 1st of each fiscal year). It found this unobjectionable because the method for calculating the total assessable amount and the subsequent premium rates was clearly laid down in the Ordinance before the assessment date. This pre-established framework left no room for arbitrary decision-making that could undermine legal stability, even if the final figures were determined post-assessment date.

On the Denial of Premium Reduction/Exemption

Regarding X's claim about the denial of premium reduction or exemption, the Supreme Court upheld the lower court's finding. The NHI Act (Article 77) allows insurers to grant reductions or exemptions by ordinance for those with "special reasons." The Asahikawa Ordinance (Article 19, Paragraph 1) provided for such reductions for individuals facing significant hardship due to disasters or sudden, substantial income decreases. It did not, however, provide for exemptions for those in a state of chronic poverty.

The Court reasoned that the NHI system presumes that individuals in chronic poverty will be covered by public assistance programs like the Livelihood Protection Act, which includes medical aid, and thus excludes them from NHI coverage (NHI Act, Article 6, Item 6). Furthermore, the Ordinance already contained provisions (Article 17) for reducing the flat-rate portions of premiums for low-income households, addressing ability to pay to some extent. The income-based portion, by its nature, reflects ability to pay.

Therefore, the Court found that the Ordinance's focus on temporary hardship for exemptions, rather than chronic poverty, was not beyond the scope of delegation under the NHI Act, nor was it grossly unreasonable or a violation of Article 25 (right to maintain minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living) or Article 14 (equality under the law) of the Constitution.

Conclusion and Broader Significance

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal. The Asahikawa City National Health Insurance Ordinance Case is a pivotal judgment. It clearly distinguishes between "taxes" directly subject to Article 84 of the Constitution and other compulsory public levies like NHI premiums. While Article 84 does not directly apply to the latter, its "spirit" does, necessitating an appropriate level of legal control and clarity.

The Court's framework allows for flexibility, recognizing that the stringency of this control can vary based on the levy's nature, purpose, and degree of compulsion. The "purpose-limitation" of NHI premiums (being earmarked exclusively for NHI program expenses) and the existence of democratic oversight through the municipal council's budgetary review were key factors in the Court's assessment that the Asahikawa Ordinance, despite delegating aspects of rate-setting to the Mayor, satisfied the constitutional concerns embodied in the spirit of Article 84.

This decision provides a crucial interpretive lens for assessing a wide range of compulsory charges imposed by public authorities in Japan, balancing the need for legal certainty and democratic control with the practical requirements of administering complex social programs. It underscores that while not all public levies are "taxes," they are not beyond constitutional scrutiny concerning the legitimacy and clarity of their imposition. The ruling emphasizes a nuanced, context-specific analysis rather than a one-size-fits-all approach to parliamentary control over public financial burdens.