Defining "Suspension of Payments" in Japanese Bankruptcy Law: Two Key Supreme Court Insights

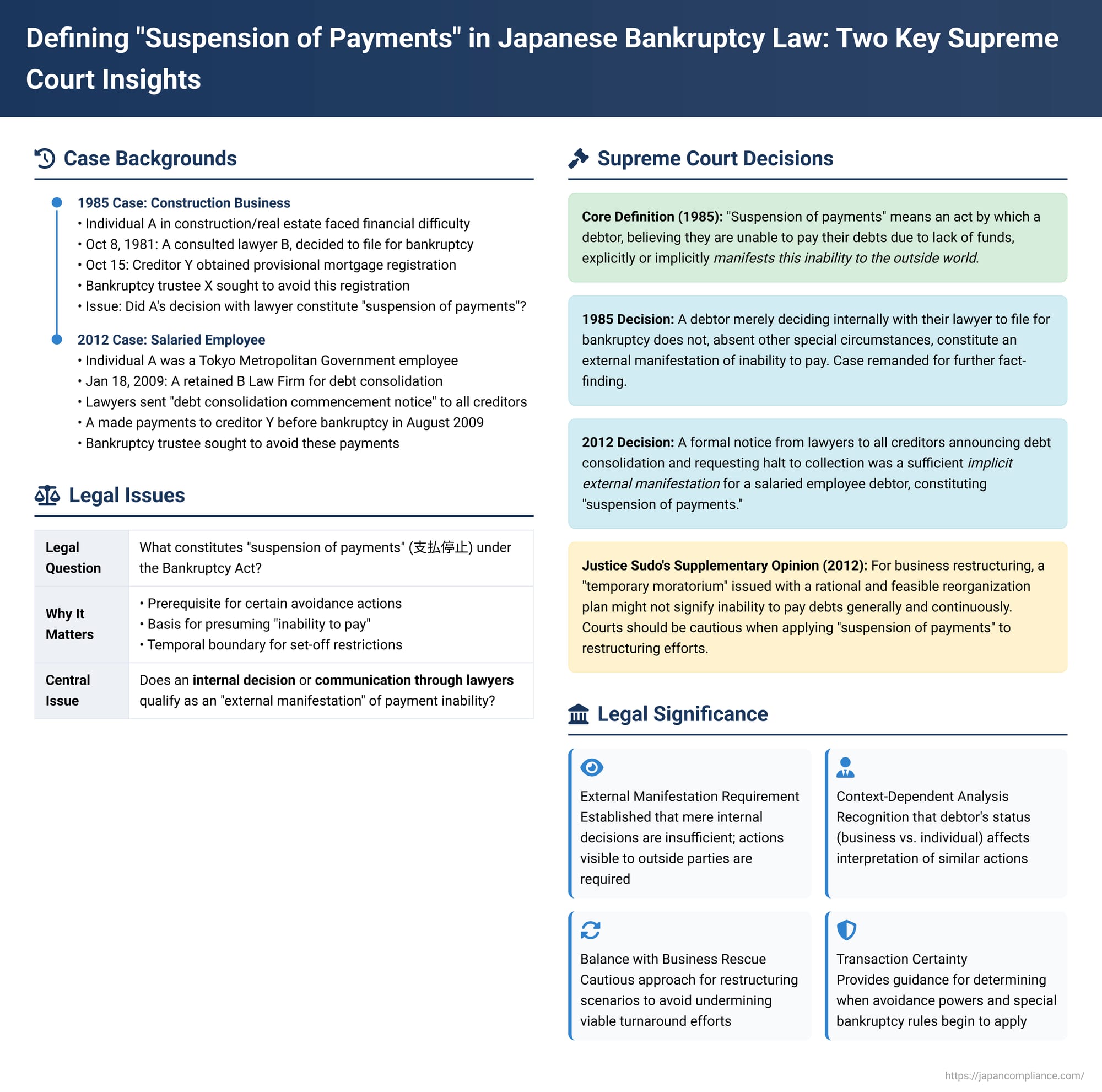

The concept of "suspension of payments" (支払停止 - shiharai teishi) is a critical trigger point in Japanese bankruptcy law, impacting various aspects from the avoidance of preferential transactions to the presumption of a debtor's inability to pay. Two pivotal Supreme Court judgments, one from 1985 and another from 2012, have provided essential definitions and application guidelines for this term, shaping its interpretation in both individual and corporate insolvency scenarios.

Defining "Suspension of Payments": The 1985 Supreme Court Judgment (Showa 60)

The first landmark decision, delivered by the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court on February 14, 1985, arose from a case involving an individual (A) in the construction and real estate business who faced escalating financial difficulties. A had borrowed money from a creditor (Y) and provided documents for a provisional mortgage registration. As A's situation worsened, A consulted a lawyer (B) and, on October 8, 1981, they decided A would file for bankruptcy. Subsequently, Y, having learned of A's consultations, obtained new documents from A and completed the provisional mortgage registration on October 15, the same day A's lawyer filed the bankruptcy petition. The bankruptcy trustee (X) later sought to avoid this registration, arguing it occurred after A had suspended payments.

The High Court had found that A suspended payments at the latest by October 8, when the decision to file for bankruptcy was made with the lawyer. However, the Supreme Court reversed this, providing a foundational definition:

"Suspension of payments" under the (then old) Bankruptcy Act means an act by which a debtor, believing they are unable to pay their debts due to a lack of funds, explicitly or implicitly manifests this inability to the outside world.

Applying this definition, the Supreme Court clarified that a debtor merely deciding internally with their lawyer to file for bankruptcy does not, in the absence of other special circumstances, constitute an external manifestation of the inability to pay. It remains an internal decision. The High Court had erred by not sufficiently examining whether there had been an external display of this inability by October 8. This judgment underscored the crucial element of "external manifestation" for a suspension of payments to be recognized.

Applying the Definition: The 2012 Supreme Court Judgment (Heisei 24) – A Lawyer's Notice to Creditors

The second significant decision, from the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court on October 19, 2012, involved an individual debtor (A), who was a salaried employee of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. On January 18, 2009, A retained a law firm (B Law Firm) for debt consolidation. Around that date, the lawyers sent a "debt consolidation commencement notice" to all of A's creditors, including Y. This notice stated that the law firm had been retained by A for debt consolidation and requested that creditors cease all contact and collection activities against A and their family. However, the notice did not detail A's debts, the specific consolidation plan, or explicitly state an intention to file for bankruptcy. Subsequently, A made several payments to Y before A's bankruptcy proceedings commenced in August 2009. The bankruptcy trustee (X) sought to avoid these payments as preferential acts, arguing they were made after a suspension of payments.

The High Court had found that this notice did not constitute a suspension of payments. The Supreme Court, however, reversed the High Court's decision. It first reiterated the definition of "suspension of payments" established in the 1985 judgment (an act by which a debtor, believing they lack the ability to pay their debts generally and continuously due to lack of funds, explicitly or implicitly manifests this inability to the outside world).

Applying this definition to the facts, the Supreme Court found that:

- The notice clearly stated that A, the debtor, had entrusted debt consolidation—a process implying seeking deferral or reduction of payments—to legal professionals.

- The lawyers, acting for A, requested all creditors to halt collection efforts, indicating an intention to achieve a uniform and fair settlement of debts.

- Crucially, the Court considered A's status as a salaried employee, not someone engaged in widespread business activities. In this context, such a formal notice from lawyers to all creditors, even without an explicit declaration of intent to file for bankruptcy, was deemed a sufficient implicit external manifestation that A lacked the ability to pay their debts generally and continuously.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that the sending of this debt consolidation notice by A's lawyers to the creditors constituted a "suspension of payments" under the Bankruptcy Act.

The Nuance: "External Manifestation" and Debtor's Circumstances

Comparing these two landmark cases highlights that the determination of "external manifestation" is highly fact-dependent.

- In the 1985 case, an internal decision between the debtor and his lawyer to pursue bankruptcy was insufficient on its own. The act of the debtor later posting a sign on his door stating a lawyer was managing his affairs, which happened on October 14, was an external act, but the court was focused on whether the earlier decision on October 8 was itself a suspension. The Supreme Court remanded for further fact-finding regarding any external manifestation linked to the earlier date.

- In the 2012 case, a formal communication from the debtor's legal representatives to all creditors announcing debt consolidation and requesting a halt to collection was deemed a sufficient external manifestation for an individual salaried debtor. The debtor's personal (non-business) status played a role in how this communication was interpreted.

Suspension of Payments in Business Restructuring: Justice Sudo's Supplementary Opinion

The 2012 judgment included an important supplementary opinion by Justice Masahiko Sudo, which addressed the complexities of applying the "suspension of payments" concept to larger enterprises undergoing restructuring efforts.

Justice Sudo cautioned that a more careful assessment is needed when larger businesses, which might possess valuable operational resources despite financial distress, issue notices of a "temporary moratorium" (一時停止 - ichiji teishi) to financial institutions or other creditors as part of a formal restructuring plan. He reasoned:

- If a company presents a rational and feasible reorganization plan that has a high probability of achieving creditor consensus, such a temporary halt in payments might not necessarily signify an inability to pay debts generally and continuously. The company may fully intend and be capable of resuming payments under the restructured terms.

- Finding a "suspension of payments" too readily in such situations could have adverse consequences. It might deter lenders from providing essential new financing (e.g., debtor-in-possession financing) for the company's turnaround, as any subsequent repayments could become vulnerable to avoidance actions. This could ultimately stifle genuine business rescue efforts.

- Conversely, Justice Sudo also noted that if a proposed restructuring plan is clearly unreasonable or lacks any realistic prospect of success, the act of requesting a payment stop might indeed be viewed as an indication of inevitable collapse and thus a suspension of payments, making fairness considerations for later avoidance or set-off restrictions paramount.

This supplementary opinion signals a judicial recognition of the need for a nuanced approach, particularly for businesses attempting organized turnarounds, where a temporary, negotiated halt in payments may be a necessary step towards recovery rather than an admission of terminal insolvency.

Significance and Current Relevance of "Suspension of Payments"

The concept of "suspension of payments" remains highly relevant under the current Japanese Bankruptcy Act. It serves as:

- A prerequisite for certain types of avoidance actions (e.g., avoidance of acts detrimental to creditors or certain security provisions made after suspension, under Articles 160(1)(2), 160(3), and 164(1)).

- A basis for presuming a debtor's "inability to pay" (支払不能 - shiharai funō), which is a primary ground for commencing bankruptcy proceedings (Article 15(2)).

- A factor in presuming insolvency for the purpose of avoiding preferential payments (Article 162(3)).

- A temporal boundary for certain restrictions on the right of set-off (Articles 71(1)(3) and 72(1)(3)).

The Supreme Court's definitions and applications in these two cases provide essential interpretative guidance. The 1985 decision established the core definition requiring an external manifestation of inability to pay, moving beyond purely internal intentions. The 2012 decision demonstrated how this definition applies in the context of modern debt consolidation practices for individuals, while Justice Sudo's opinion in that same case introduced important considerations for business restructurings, suggesting that the legal characterization of a payment halt can depend on the broader context of rescue efforts and the viability of proposed plans. The ongoing legal discourse continues to explore the balance between maintaining a clear, formal definition of "suspension of payments" and adapting its application to the diverse realities of financial distress and the policy goals of both creditor protection and business rehabilitation.

Concluding Thoughts

The Japanese Supreme Court, through these key judgments, has shaped the understanding of "suspension of payments" as a critical legal marker in bankruptcy. The core principle remains that a debtor must externally manifest, either explicitly or implicitly, their inability to meet obligations due to a lack of funds. However, what constitutes such a manifestation is context-dependent, as illustrated by the differing outcomes based on the specific actions and status of the debtors in the 1985 and 2012 cases. Furthermore, the cautious approach advocated for business restructurings signals an evolving jurisprudence that seeks to align the application of this important bankruptcy concept with the practical needs of facilitating viable turnarounds while safeguarding the fairness of the insolvency process.