Defining "Solicitation" in the Age of Mass Advertising: Japan's Supreme Court Weighs In on Chlorella Flyers

Judgment Date: January 24, 2017

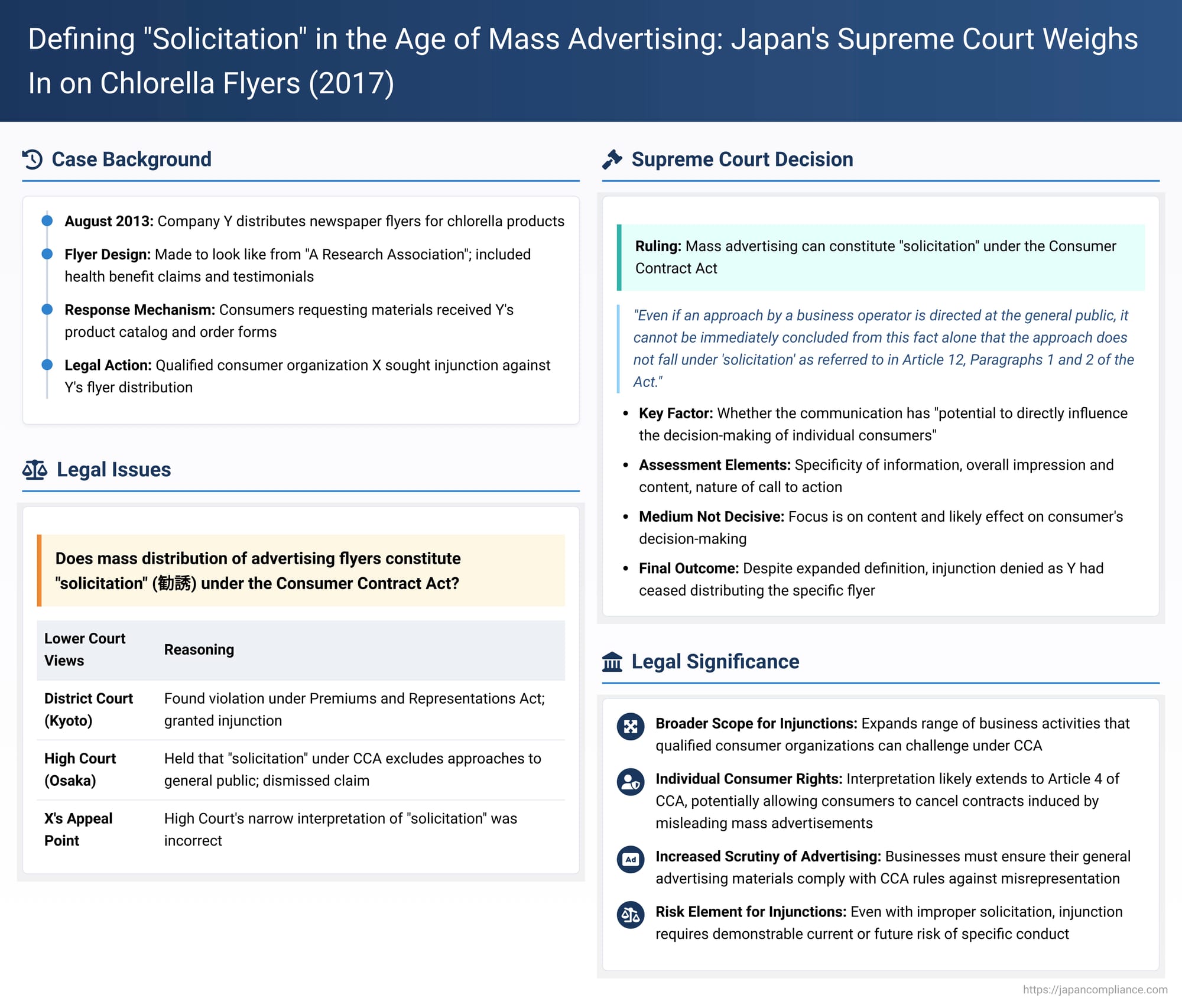

In a significant ruling for consumer protection in Japan, the Supreme Court's Third Petty Bench on January 24, 2017, delivered a judgment in the "Chlorella Flyer Distribution Injunction Request Case" (Heisei 28 (Ju) No. 1050). This case tackled a pivotal question: can the mass distribution of advertising materials, such as newspaper flyers, constitute "solicitation" (勧誘 - kan'yū) under Japan's Consumer Contract Act (CCA)? The Court's decision provided crucial clarification on the scope of activities that can be challenged by consumers and qualified consumer organizations.

The Factual Backdrop: Chlorella Claims and Consumer Concerns

The defendant, Y, a company engaged in selling health foods derived from chlorella, undertook a promotional campaign in August 2013. This involved distributing a flyer (referred to as the "Flyer") via newspaper inserts within a major Japanese city.

The Flyer itself was designed to appear as if it originated from an entity named "A Research Association." Its content included various claims about the benefits of chlorella, such as its ability to regulate the immune system and invigorate cellular activity. Furthermore, it featured testimonials from individuals who purportedly experienced recovery from a range of ailments—including hypertension, back pain, and diabetes—through chlorella consumption. The mechanism set up was that individuals who requested informational materials from A Research Association, based on the Flyer, would then be sent Y’s product catalog and order forms, enabling them to purchase Y’s chlorella products.

The plaintiff, X, a qualified consumer organization as defined under Article 2, Paragraph 4 of the Consumer Contract Act, took issue with Y's promotional activities. X filed a lawsuit seeking an injunction to halt the distribution of the Flyer by Y. X argued that the representations made in the Flyer were misleading. Specifically, X contended that the Flyer's claims constituted either:

- A misleading representation of superiority (優良誤認表示 - yūryō gonin hyōji) under Article 10, Paragraph 1, Item 1 (now Article 30, Paragraph 1, Item 1) of the Act against Unjustifiable Premiums and Misleading Representations (commonly known as the "Premiums and Representations Act").

- A misrepresentation of material facts (不実告知 - fujitsu kokuchi) as stipulated in Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Consumer Contract Act, which is referenced in Article 12, Paragraphs 1 and 2 of the CCA (the provisions under which qualified consumer organizations can seek injunctions).

The Legal Journey: Lower Courts Divided on "Solicitation"

The case progressed through the lower courts with differing outcomes and reasoning:

- First Instance (Kyoto District Court): The District Court found that A Research Association was, in effect, a division of Y company. It concluded that Y’s advertisement in the Flyer constituted a "misleading representation of superiority" under the Premiums and Representations Act. Consequently, the court granted X’s request for an injunction based on this Act. Y appealed this decision.

- Second Instance (Osaka High Court): The High Court took a different view.

- Regarding the claim under the Premiums and Representations Act, the High Court overturned the District Court's decision. It noted that, at the time of its ruling, flyers containing the expressions found problematic by the first instance court were no longer being distributed. Furthermore, Y had explicitly stated it would not distribute such flyers in the future. The High Court thus found no current or imminent future risk of such misleading representations being made, and therefore, deemed an injunction unnecessary under this Act.

- Regarding the claim under Article 12 of the Consumer Contract Act, the High Court also dismissed X's request. Its reasoning was critical: it held that the term "solicitation" as used in Article 12, Paragraphs 1 and 2 of the CCA does not include approaches made by businesses towards the general, unspecified public. Since the distribution of the Flyer was an act targeting a broad and indefinite number of newspaper subscribers, the High Court concluded it did not qualify as "solicitation" under the CCA.

It was this narrow interpretation of "solicitation" under the CCA by the High Court that X appealed to the Supreme Court. The Supreme Court accepted the appeal specifically on the question of whether the distribution of the Flyer constituted "solicitation" under Article 12, Paragraphs 1 and 2 of the Consumer Contract Act.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Interpretation of "Solicitation"

The Supreme Court ultimately dismissed X's appeal. However, its reasoning regarding the definition of "solicitation" diverged significantly from that of the High Court and established an important precedent.

The Court began by noting that the Consumer Contract Act aims to protect consumers' interests, recognizing the disparities in information quality, quantity, and negotiating power between consumers and businesses (CCA Article 1). The Act allows consumers to rescind contracts formed due to certain misleading or coercive solicitation practices by businesses (CCA Articles 4 and 5). To prevent or mitigate consumer harm, the CCA also empowers qualified consumer organizations to seek injunctions against businesses engaging in or likely to engage in such improper solicitation practices (CCA Article 12).

The Supreme Court then directly addressed the meaning of "solicitation" within these provisions, for which the CCA provides no explicit definition. The Court stated:

"For example, when a business operator makes an approach to the general public through a newspaper advertisement, the overall content of which allows consumers to specifically recognize the content of the business operator's goods, transaction terms, or other matters related to these transactions, such an approach may directly influence the decision-making of individual consumers. Therefore, to uniformly exclude cases where a business operator, etc., makes an approach to the general public from the scope of 'solicitation' under the aforementioned provisions, deeming them not to fall under 'solicitation,' is difficult to consider appropriate in light of the purpose and objectives of the Act."

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court concluded:

"Therefore, even if an approach by a business operator, etc., is directed at the general public, it cannot be immediately concluded from this fact alone that the approach does not fall under 'solicitation' as referred to in Article 12, Paragraphs 1 and 2 of the Act."

This was a pivotal clarification. The Supreme Court effectively ruled that mass advertising or other forms of outreach to the general public can indeed fall within the scope of "solicitation" under the Consumer Contract Act. The High Court's categorical exclusion of such activities was thus deemed an error in legal interpretation. This ruling aligned with the prevailing academic view, which had long argued for a broader interpretation of "solicitation" that includes any act specifically aimed at influencing a consumer's decision to enter into a contract, regardless of whether it targets a specific individual or the public at large.

When Does General Outreach Cross the Line into "Solicitation"?

While the Supreme Court broadened the potential scope of "solicitation," it did not imply that all forms of advertising or general communication by businesses automatically qualify. The key lies in the nature and potential impact of the communication.

The Court's reasoning suggests that an approach to the general public may be considered "solicitation" if it has the potential to "directly influence the decision-making of individual consumers." This "direct influence potential" seems to be the crucial determinant. This potential is likely assessed by considering elements such as:

- Specificity of Information: Does the communication provide concrete details about the product or service, its features, price, transaction terms, or other relevant information that would allow a consumer to form a specific understanding and potentially a decision to contract? The Supreme Court's example of a newspaper ad allowing consumers to "specifically recognize" such details points to this.

- Overall Impression and Content: The entire context of the communication matters. Even if some details are omitted from the initial advertisement (like in this case, where the Flyer itself didn't name Y's specific products but led to a catalog), if the overall scheme is designed to draw consumers towards a specific transaction, it could be considered part of a solicitation process.

- Nature of the Call to Action: Does the communication invite a response that directly leads to a transactional opportunity? The Flyer leading to Y's catalog and order forms suggests such a link.

The judgment implies that the medium of communication (e.g., newspaper flyer, internet advertisement, television commercial) is not, in itself, decisive. Rather, it is the content, presentation, and the likely effect on the average consumer's decision-making process that will be scrutinized. The assessment should be based on how a general consumer would understand and perceive the communication.

The threshold for an act to be considered "solicitation" serves as an entry point for the protections under the CCA. Since the specific types of improper solicitation are detailed in Article 4 of the Act (misrepresentation, non-disclosure of disadvantageous facts, etc.), legal scholars suggest that this initial "solicitation" requirement itself need not be interpreted with excessive stringency.

The Twist: Why the Injunction Was Ultimately Denied by the Supreme Court

Despite its groundbreaking interpretation of "solicitation," the Supreme Court ultimately upheld the High Court's decision to dismiss X’s claim for an injunction under the Consumer Contract Act. This was not due to the definition of "solicitation" but because of a different requirement for granting an injunction.

Article 12 of the CCA allows a qualified consumer organization to seek an injunction if a business "is currently committing or is likely to commit" the prohibited acts during solicitation. The Supreme Court, referring to the factual findings of the lower court (which it generally does not overturn unless there's a clear legal error in their establishment), noted that Y was no longer distributing the specific Flyer in question (which contained the problematic health claims and testimonials) from January 22, 2015. Moreover, Y had started distributing a new flyer without these claims from June 29, 2015, and had explicitly stated that it would not distribute the original, problematic Flyer in the future.

Based on these facts, the Supreme Court concluded that it could not be said that Y "is currently committing or is likely to commit" the act of distributing that specific problematic Flyer. Therefore, the necessary condition for issuing an injunction under Article 12—a present or future risk of the specific harmful conduct—was not met in this particular instance. The High Court's dismissal of the injunction request was, therefore, affirmed in its conclusion, albeit on different grounds regarding the legal definition of "solicitation."

Implications for Consumer Protection and Business Practices

The Supreme Court's decision carries significant implications:

- Broader Scope for Injunctions: By clarifying that "solicitation" under the CCA can include mass advertising, the ruling expands the range of business activities that qualified consumer organizations can challenge. Misleading or otherwise improper claims made in advertisements targeting the general public can now more clearly be subject to injunction requests under CCA Article 12, provided there is an ongoing or future risk.

- Potential Impact on Individual Consumer Rights (CCA Article 4): While the Supreme Court's direct ruling was on Article 12 (injunctions), its interpretation of "solicitation" is widely considered to extend to Article 4 of the CCA. Article 4 allows individual consumers to cancel contracts if their offer or acceptance was made due to certain types of improper solicitation by the business (e.g., misrepresentation of material facts). If a mass advertisement is deemed "solicitation" and contains such a misrepresentation that induces a consumer to enter into a contract, the consumer may have grounds to cancel. It is important to note, however, that Article 4 has additional requirements for cancellation, including the actual misrepresentation or other proscribed conduct, and a causal link between that conduct and the consumer's decision to contract.

- Increased Scrutiny of Advertising Content: Businesses must be more mindful that their general advertising materials could be classified as "solicitation" under the CCA. This subjects such advertisements to the Act's rules against misrepresentation, assertive opinions as conclusive facts, non-disclosure of disadvantageous information, and other problematic practices during the "solicitation" phase.

- Importance of the "Risk" Element for Injunctions: The case also underscores that even if an act is deemed improper solicitation, an injunction will only be granted if there is a demonstrable current or future risk of that specific conduct occurring. Corrective action by a business, such as ceasing the problematic advertisement and committing not to resume it, can be a crucial factor in avoiding an injunction.

Conclusion: A Clearer, Broader Definition of "Solicitation"

The Supreme Court's judgment in the Chlorella Flyer case marks a significant development in Japanese consumer law. By affirming that approaches to the general public can indeed constitute "solicitation" under the Consumer Contract Act, the Court has strengthened the tools available to protect consumers from misleading or unfair practices in a broad range of commercial communications. While the ultimate dismissal of the injunction in this specific case turned on factual findings regarding the cessation of the problematic activity, the Court's legal interpretation of "solicitation" provides a clearer and more expansive framework for evaluating the responsibilities of businesses in their interactions with consumers, whether individual or en masse.