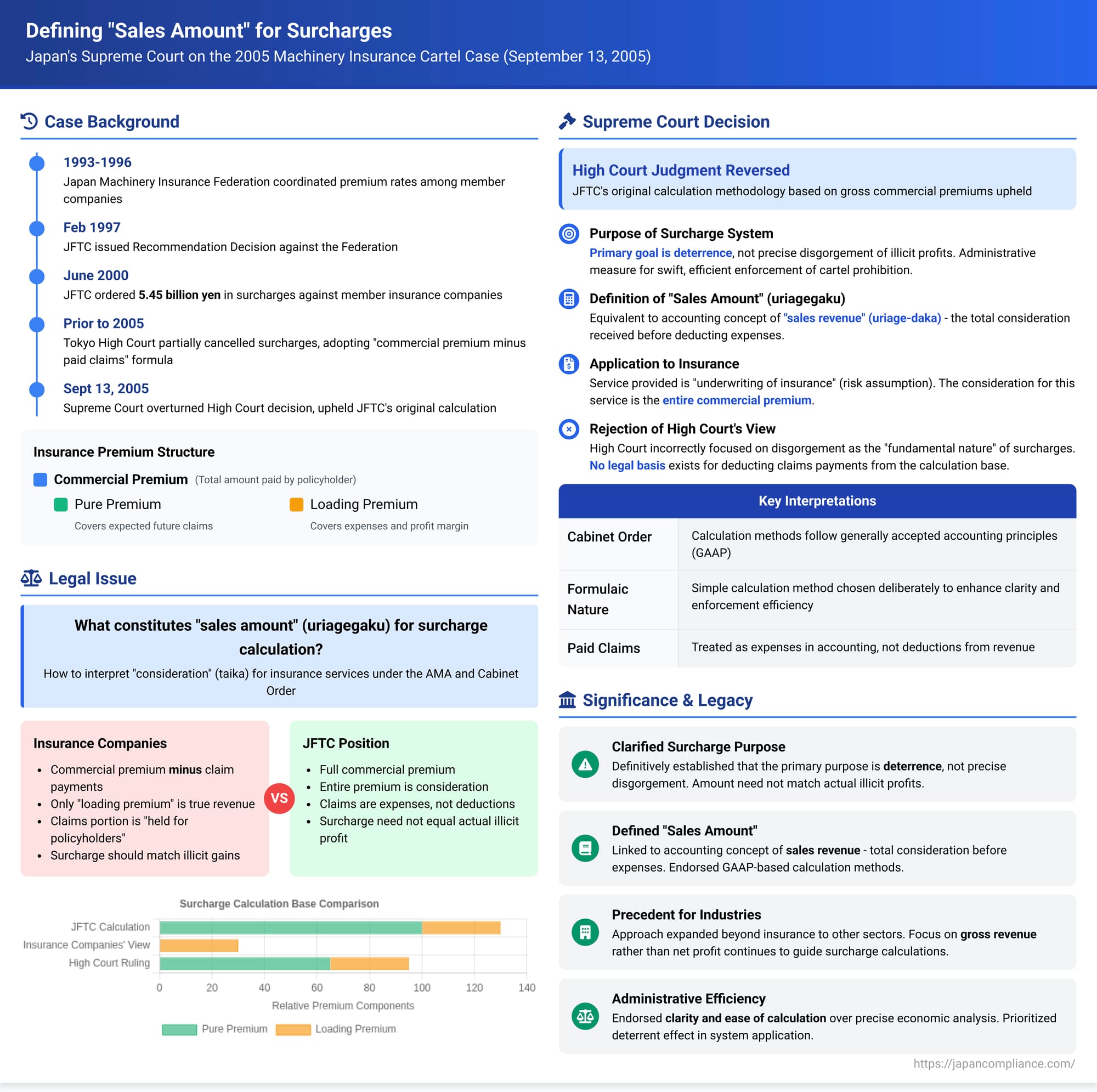

Defining "Sales Amount" for Surcharges: Japan's Supreme Court on the 2005 Machinery Insurance Cartel Case

Decision Date: September 13, 2005 (Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench)

Introduction

This 2005 Supreme Court of Japan judgment provides a foundational interpretation of how administrative surcharges (kachōkin) are calculated under Japan's Antimonopoly Act (AMA). The case arose from a price-fixing cartel orchestrated by Federation A (the Japan Machinery Insurance Federation), a trade association for insurers offering machinery and erection insurance. The Japan Fair Trade Commission (JFTC) imposed substantial surcharges on the member insurance companies. The core legal dispute centered on the definition of "sales amount" (uriagegaku) – the base figure used for calculating these surcharges – in the context of insurance services. The insurance companies argued for deductions from the total premiums collected, while the JFTC insisted on using the gross premium amount. The Supreme Court's decision clarifies the purpose of the surcharge system and establishes key principles for determining the relevant "sales amount."

Background: The Cartel, Surcharges, and the Dispute

The case involved the following key elements:

- The Cartel Participants: Federation A was a trade association (jigyōsha dantai) under AMA Article 2(2), whose members were licensed non-life insurance companies providing machinery insurance and erection insurance (collectively, "Machinery Insurance, etc."). The appellees in the Supreme Court (Insurance Companies X) were member companies of this federation.

- The Violation: The JFTC found that between March 7, 1993, and March 6, 1996 ("the Relevant Period"), Federation A engaged in conduct violating AMA Article 8(1)(i). This provision prohibits trade associations from substantially restricting competition in any particular field of trade. Federation A achieved this by dictating the specific premium rates that its member insurance companies were required to apply when underwriting Machinery Insurance, etc., effectively fixing the price for these services.

- JFTC Enforcement Actions:

- Order against the Federation: The JFTC first issued a Recommendation Decision (kankoku shinketsu) against Federation A itself in February 1997, ordering it to cease the illegal conduct.

- Surcharge Orders against Members: Subsequently, following formal administrative hearing procedures (shinpan), the JFTC issued surcharge payment orders (kachōkin nōfu meirei) against the individual member companies (Insurance Companies X) on June 2, 2000, pursuant to AMA Article 8-3 (which incorporates the surcharge calculation rules from Article 7-2). The total surcharge amount ordered was approximately 5.45 billion yen.

- Surcharge Calculation Method:

- Statutory Framework: The AMA (pre-2005 amendments version) stipulated that when a trade association engages in a price cartel for goods or services (violating Art. 8(1)(i)), its member companies participating in the conduct must pay a surcharge. The amount is calculated based on the "sales amount" (uriagegaku) of the affected goods or services during the period the cartel was implemented ("Relevant Period"), multiplied by a statutory rate (generally 6%, with variations for certain industries or company sizes – e.g., 3% for Company D in this case).

- Defining "Sales Amount": The Cabinet Order implementing the AMA (Dokkinhō Shikōrei) Article 5 defined the method for calculating "sales amount" for services as totaling the "consideration" (taika) received for the services provided during the Relevant Period.

- JFTC's Interpretation: The JFTC determined that the "service" provided by the insurance companies was the underwriting of Machinery Insurance, etc. It concluded that the "consideration" (taika) received for this service was the full commercial insurance premium (eigyō hokenryō) collected from policyholders. Therefore, it calculated the total commercial premiums received by each company during the Relevant Period and applied the statutory percentage to this gross amount.

- Insurance Premium Structure:

- Commercial Premium (eigyō hokenryō): The total amount paid by the policyholder.

- Pure Premium (jun hokenryō): The portion theoretically allocated to cover future claims payments, based on actuarial estimates (expected loss ratio).

- Loading Premium (fuka hokenryō): The remaining portion covering operating expenses (including agent commissions) and the insurer's profit margin.

- Accounting Practice: Insurers typically record the full commercial premium received as revenue and treat claims paid out as an expense.

- The Insurance Companies' Argument: Insurance Companies X challenged the JFTC's surcharge orders in the Tokyo High Court. They argued that the "consideration" (taika) used for calculating the surcharge base should not be the full commercial premium. They contended that the portion of the premium destined to cover claims (either the pure premium component or the amount actually paid out) did not represent revenue earned by the insurer but rather funds held for policyholders. They argued the true consideration for their service (risk management, fund administration) was only the loading premium, or at most, the commercial premium minus claim payouts or pure premium. They requested cancellation of the surcharge amounts exceeding their proposed calculation bases.

- Tokyo High Court Ruling: The High Court partially agreed with the insurance companies. It emphasized that the "fundamental nature" of the surcharge system was the disgorgement of illicit economic gains derived from the cartel. Therefore, it reasoned, the term "consideration" should be interpreted in a way that makes the surcharge amount approximate this illicit gain as closely as possible. It viewed the portion of premiums used for claim payments as merely funds transferred within the insurance pool (from the collective policyholders to those who suffered losses), not as economic counter-payment to the insurer for its service. The insurer's service, in the High Court's view, was primarily managing this fund transfer. Consequently, the High Court ruled that the "consideration" constituting the surcharge base should be the commercial premium minus the actual amount paid out in claims during the Relevant Period. It cancelled the portion of the JFTC's surcharge orders exceeding this recalculated amount.

- JFTC's Appeal: The JFTC appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court, seeking reinstatement of its original surcharge orders based on gross commercial premiums.

Legal Issue Before the Supreme Court

The central question was the correct interpretation of "sales amount" (uriagegaku) under AMA Article 7-2 (applied via Art. 8-3) for the purpose of surcharge calculation in the context of insurance services. Specifically, what constitutes the "consideration" (taika) for the service of underwriting insurance: the full commercial premium, or the premium less certain deductions (like paid claims)?

Supreme Court's Analysis and Judgment

The Supreme Court unanimously reversed the High Court's decision and fully upheld the JFTC's original calculation method based on gross commercial premiums. Its reasoning addressed the fundamental purpose of the surcharge system and the specific meaning of "sales amount."

- Purpose and Nature of the Surcharge System: The Court provided a definitive statement on the surcharge system's objectives and legal character:

- Deterrence as Primary Goal: The system was introduced in 1977 alongside existing criminal penalties (AMA Art. 89) and private damages actions (AMA Art. 25). Its purpose was to strengthen the deterrent effect against cartels by increasing the financial disincentives and reducing the economic attractiveness of such conduct. It was designed as an administrative measure (gyōsei-jō no sochi) for ensuring the effectiveness of the cartel prohibition, intended to be invoked swiftly and efficiently.

- Formulaic Calculation for Clarity and Efficiency: The calculation method – multiplying the "sales amount" during the violation period by a fixed statutory rate – was deliberately chosen. As an administrative measure, clear and easily ascertainable calculation standards were deemed desirable. Furthermore, achieving the deterrent goal through active and efficient enforcement required a calculation method that was simple and straightforward. The Court explicitly stated that calculating the precise economic benefit (illicit profit) on a case-by-case basis was considered inappropriate when the system was designed and maintained.

- No Requirement for Exact Disgorgement: A direct consequence of this design philosophy is that the calculated surcharge amount does not need to precisely match the actual illicit profit obtained through the cartel. While related to the economic impact of the cartel via the sales base, its primary function is administrative deterrence through a standardized, predictable sanction. The High Court's focus on disgorgement as the "fundamental nature" was thus incorrect.

- Meaning of "Sales Amount" (Uriagegaku) and "Consideration" (Taika):

- Guidance from Cabinet Order and Accounting Principles: The Court analyzed the relevant Cabinet Order provisions (Articles 5 and 6) detailing the calculation methods (delivery basis as default, contract basis as exception) and the explicitly allowed deductions (limited to allowances for defects, returns, and certain rebates). It concluded that these provisions aim to calculate the surcharge base in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP), specifically mirroring the calculation of net sales revenue (gross sales less discounts, returns, and allowances).

- Equivalence to Accounting "Sales Revenue" (Uriage-daka): The Court further observed that the statutory rates applied to the "sales amount" were historically set by legislators with reference to average industry profit margins calculated relative to "sales revenue" (uriage-daka) as understood in corporate accounting. This accounting term represents the total consideration (price, fee) received from customers based on contracts, before deducting costs or expenses. The Court concluded that the "sales amount" (uriagegaku) used for surcharge calculation is synonymous with this accounting concept of sales revenue.

- Definition of "Sales Amount": Therefore, the "sales amount" under AMA Article 7-2 generally signifies the pre-expense revenue generated from the business activity targeted by the cartel.

- Application to the Insurance Business:

- The Service Provided: The Court defined the service provided by an insurer under a non-life insurance contract, referencing Japan's Commercial Code, as the "underwriting of insurance" – that is, promising to indemnify the policyholder against potential losses arising from specified contingent events.

- The Consideration Received: The consideration (taika) that the policyholder pays to the insurer for this service (the assumption of risk) is the entire commercial insurance premium (eigyō hokenryō).

- Conclusion: Applying its interpretation of "sales amount," the Court held that in the non-life insurance industry, the total sum of commercial premiums received constitutes the relevant "sales amount" under AMA Article 7-2 (and by reference, Art. 8-3). There is no legal basis in the AMA or its implementing order for deducting paid claims (which are expenses from an accounting perspective) or the pure premium component (an internal actuarial allocation) from this figure when calculating the surcharge base.

- Final Decision: The JFTC's original surcharge orders, calculated based on the total commercial premiums received by Insurance Companies X during the Relevant Period multiplied by the statutory rate, were deemed lawful. The Supreme Court reversed the High Court judgment that had ordered partial cancellation and dismissed all claims made by the Insurance Companies X.

Significance and Conclusion

This 2005 Supreme Court judgment is a landmark decision with lasting impact on AMA enforcement, particularly concerning the surcharge system:

- Clarifies Surcharge Purpose: It definitively established that the primary purpose of the AMA surcharge system is deterrence through administrative sanctions, not precise disgorgement of illicit profits. The amount levied does not need to equal the actual illegal gain.

- Defines "Sales Amount": It provides a clear interpretation of the crucial term "sales amount" (uriagegaku) used for surcharge calculation, linking it directly to the accounting concept of sales revenue (uriage-daka) – the total consideration received before deducting expenses. It endorsed the calculation methods based on GAAP as specified in the Cabinet Order.

- Specific Ruling for Insurance: It specifically ruled that for non-life insurance services, the relevant "sales amount" is the gross commercial premium collected, rejecting arguments for deducting paid claims or pure premiums.

- Enduring Precedent: The principles laid down in this case regarding the system's deterrent purpose and the definition of "sales amount" have been consistently followed in subsequent cases and are considered foundational for interpreting surcharge provisions across different types of AMA violations, including those introduced after 2005.

This decision underscores the administrative nature of the surcharge system and prioritizes clarity, ease of calculation, and deterrent effect in its application, even if the resulting amount diverges from the precise illicit profits obtained by the infringing parties.